Books & Culture

The Delicate Balancing Act of Black Women’s Memoir

From slave narratives to Michelle Obama, Black women must be simultaneously self-disclosing and self-protective

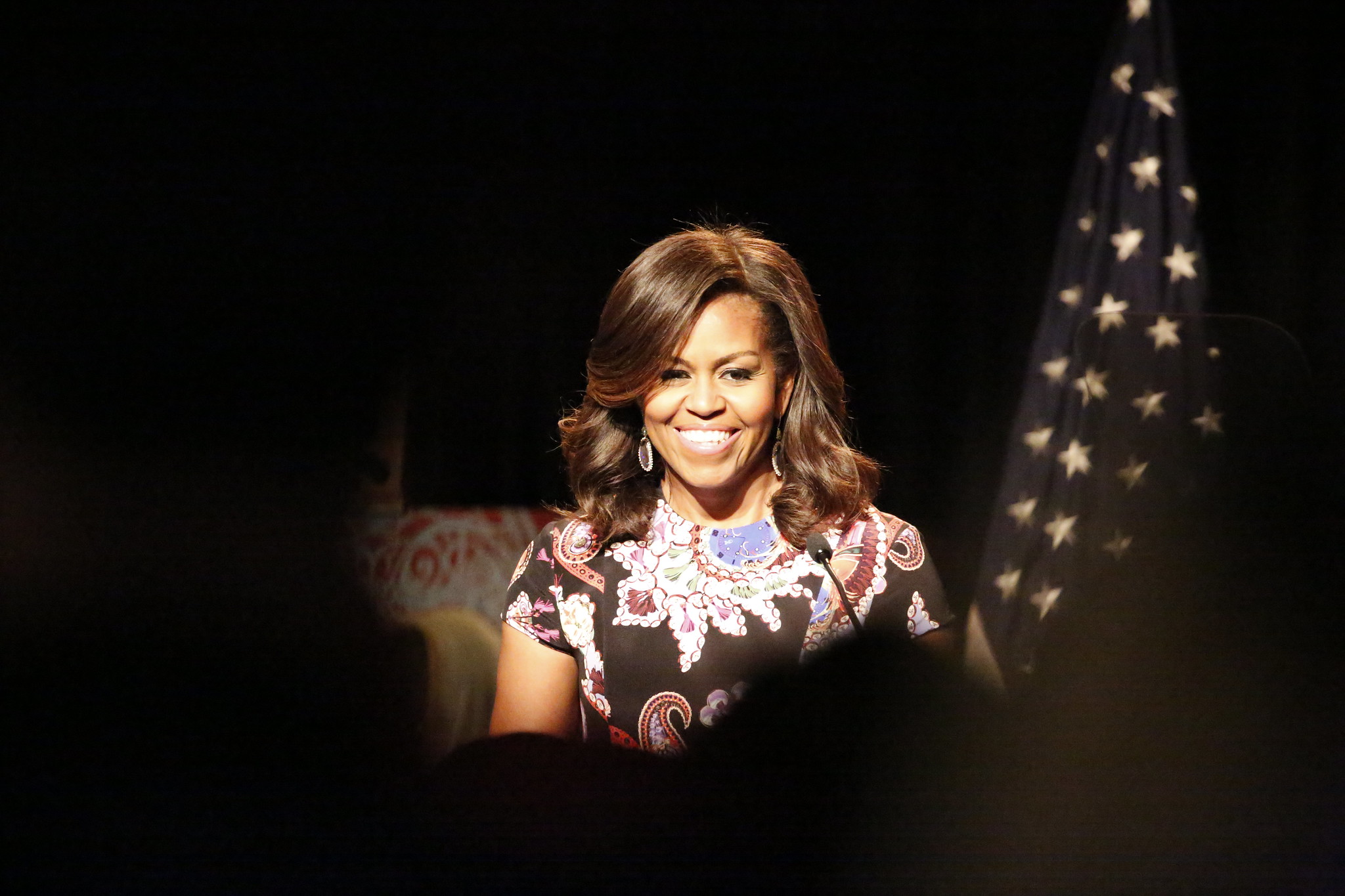

As Crown Publishing predicted, readers eagerly anticipated Michelle Obama’s Becoming. Autobiography and memoir are best-selling categories because virtually everyone enjoys learning about the private life of public figures. In this case, many were curious about the woman who seemed to rise above peculiar controversies and non-stop criticism. How had Mrs. Obama felt about being portrayed as “some angry Black woman”? A meticulous biographer had engaged these issues, but this was an opportunity to hear from the source. Did it bother her that she was criticized for wearing shorts in warm weather? Did appearing in political cartoons make her lose sleep?

Becoming delivers in that it unfolds powerfully and is a pleasure to read. Beginning with a portrait of her family of origin—including ancestors—the book shows readers how a young Michelle’s confidence was cultivated and then strengthened by challenges to it. The narrative allows readers to understand what empowered Michelle to come into her own and to maintain her sense of self as she, Barack, Sasha and Malia navigated life on the world stage. Nevertheless, the memoir is less revealing than it seems. As a result, one might learn more about Michelle Obama by seeing how little has changed since another exceptionally accomplished Black woman wrote an autobiography informed by her time in the White House.

In 1868, the self-emancipated Elizabeth Keckley published a post-Civil War slave narrative, Behind the Scenes; Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House. As Mary Todd Lincoln’s primary dressmaker and confidante, Keckley wrote the book to clear Mrs. Lincoln’s name. Lincoln had sparked an “Old Clothes Scandal” by trying to sell her wardrobe to keep afloat financially because Congress failed to provide for the widow after her husband’s assassination. Keckley’s narrative style is striking for how skillfully she shields personal experiences while telling her life story. She declares, “The veil of mystery must be drawn aside” because “my own character, as well as the character of Mrs. Lincoln, is at stake”—but she places the Lincoln family on display, not her own.

Mrs. Obama has mastered seeming to be available to the American public while fiercely protecting one’s inner life.

Mrs. Obama has mastered the same skill that shapes Keckley’s work, seeming to be available to the American public while fiercely protecting one’s inner life. As Mrs. Obama continues Keckley’s legacy, they both participate in what historian Darlene Clark Hine famously termed “a culture of dissemblance.” African American women create “the appearance of disclosure, or openness about themselves and their feelings, while actually remaining an enigma.”

Hine’s concept is about more than the simple desire for privacy. A “culture of dissemblance” has developed because “the relationship between Black women and the larger society has always been, and continues to be, adversarial.” That is, American culture maligns Black women in every possible way, arguably as a matter of course, beginning with the constant portrayal of them as natural whores who cannot be raped. Insisting that Black women so willingly gave themselves and indeed ensnared white men was the foundation on which the United States literally built its wealth in human property. Not surprisingly, then, Keckley’s life story was shaped by rape. Behind the Scenes recounts: a white man “had base designs upon me. … Suffice it to say, that he persecuted me for four years, and I—I—became a mother.”

Just as Keckley refuses to offer specifics, Michelle Obama need not dwell on details for her experience to spotlight American culture’s adversarial approach to Black women. Becoming mentions the political cartoon in which Mrs. Obama was depicted with a machine gun, fist-bumping her husband, but it omits how predictably she was compared to a man, an ape, and a gorilla. And yet, because American culture is geared toward reminding everyone who isn’t a straight white man of their “proper” place as subordinates, these responses are common. When I tweeted “The Secret to Michelle Obama’s ‘Most Admired’ Status,” my Twitter mentions suddenly contained masculinized images of the former First Lady. A Black woman is succeeding? Time to take her (and those who value her) down a peg.

In a society invested in casting Black women as deviants, withholding one’s full humanity is not simply reactive; it’s proactive.

Super-dignified moments like “When they go low, we go high” should be understood as part of this culture of dissemblance. In a society invested in casting Black women as sexual deviants and unfit mothers as well as financially and morally bankrupt leeches, withholding one’s full (flawed) humanity is not simply reactive; it’s proactive. According to Hine, “achieving a self-imposed invisibility” allows Black women to “collectively create alternative self-images and shield from scrutiny these private, empowering definitions of self.” In other words, when Black women remain enigmas while seeming to share so much, they create proxies at a distance from their psychic and spiritual realities because they are so rarely safe in public. Despite the release of her memoir, audiences will never be privy to who Michelle Obama actually knows herself to be, and that is more than appropriate.

In Keckley, dissemblance shows up most profoundly around sorrow. When the Lincolns lose their son Willie, Keckley offers particulars that highlight the family’s pain. She follows this detailed scene with a single paragraph about the death of her own son. She says, “previous to this I had lost my son,” who had joined the Union army after having attended Wilberforce. Immediately after this paragraph, she exposes the Lincolns’ mourning even more by reproducing a newspaper tribute to Willie that Mrs. Lincoln had saved in a scrapbook. By making brief, passing mention of her son’s death in a story about her own life, Keckley keeps her struggle private. This is remarkable because, as a genre, slave narratives rely on the conflation of Black identity with pain. As literary critic Janet Neary explains, Keckley applies her sewing expertise to writing, by “ripping the slave narrative apart at the seams and refashioning it.” Dissembling is key to this refashioning. Keckley appears to reveal so much while shielding from public view her innermost thoughts and feelings. In a space synonymous with whiteness and power, the White House, Keckley claims privacy for herself and her family. She secures what the nation robbed her of when she lived in a slave cabin… and in the white home she later occupied as housekeeper when she was raped.

Mrs. Obama has been as deliberate as Keckley in constructing her self-image both in how she embodies her role in public and in her memoir. Michelle Obama’s persona as FLOTUS was one of welcoming warmth—an absolute feat in a society determined to see Black women as angry. Mrs. Obama’s comforting aura hinged on her insistence upon performing Mom-in-Chief, complete with an emphasis on gardening. Her Princeton and Harvard degrees faded into the background, along with her executive experience at the University of Chicago Medical Center. Another strategy she consistently used, which didn’t surprise anyone familiar with the nation’s tendencies toward Black people, was to take what seemed to be every opportunity to teach white folk how to dance.

Mrs. Obama’s success as First Lady required helping Americans to forget the fullness of her humanity.

The Michelle Obama who performed in these ways was no less aware of the nation’s racial politics than she had been before becoming First Lady, but she had seen how swift punishment could be for speaking her truth. The Obama campaign had to take her out of the public eye in February 2008 after she admitted, “for the first time in my adult lifetime, I am really proud of my country.” Given the vitriol white Americans felt justified spewing after that remark, Mrs. Obama’s success as First Lady—because of Americans’ shortcomings, not her own—required helping them to forget the fullness of her humanity.

FLOTUS needed to conceal not only her understanding of who she was and who her family was, but also her awareness of who white Americans often proved themselves to be. To appreciate the labor required for, in Hine’s words, “achieving a self-imposed invisibility,” please recall Obama’s February 2007 60 Minutes interview. When asked if she feared for her husband’s life as a Black candidate, Mrs. Obama responded, “I don’t lose sleep over it because the realities are that . . . as a Black man . . . Barack can get shot going to the gas station” (emphasis added). Inevitably, Mrs. Obama’s performance as Mom-in-Chief was inflected by her awareness that racist violence undergirds U.S. culture. To recognize that her husband could be shot going to the gas station was to evoke the realities of the racial profiling that results in Black and Brown men disproportionately dying at the hands of police.

Even if one insists that, given her familiarity with gun violence in Chicago, Michelle Obama had been thinking of Black men dying from other Black men’s gunfire, that would still gesture toward the country’s systematic devaluation of Black life. As cultural critic Ta-Nehisi Coates has explained, the structures that all but ensure African Americans’ civic, social, and economic exclusion also cause their deaths. “Spare us the invocations of ‘black-on-black crime,’” Coates writes, “I will not respect the lie. . . . The most mendacious phrase in the American language is ‘black-on-black crime,’ which is uttered as though the same hands that drew red lines around the ghettos of Chicago are not the same hands that drew red lines around the life of Jordan Davis [and Hadiya Pendleton].” Likewise, Michelle Obama had suggested that, whether political candidates or ordinary citizens, African Americans become targets because the nation consistently casts them as not only unfit for inclusion but downright disposable.

It feels like a stretch to connect a Michelle Obama comment to Coates’s condemnation of the violence woven into purportedly civil discourse, doesn’t it? That’s a testament to the skill with which she participates in the culture of dissemblance, which allows her to enjoy privacy in public. Like Keckley, she recognizes that the mainstream gaze cannot be trusted when it lands on a Black woman’s truth. When Keckley foregrounds the Lincoln family’s grief and glides past her own, she reverses the spectacle expected in a slave narrative. Her story begins with an account of enslavers separating her family of origin, but her memoir later places the spotlight on a white family in distress. The reversal is not about exacting textual vengeance on white people; it’s about highlighting the achievement of having moved from slave cabins to the White House.

Mrs. Obama’s public persona is a success-oriented cultural production—even if, or especially because, most Americans fail to see it as such.

White Americans devastated Black families and swore they never existed, and that is the lens through which to view black cultural production that spotlights African American accomplishment. Mrs. Obama’s public persona is one such success-oriented cultural production—even if, or especially because, most Americans fail to see it as such. Indeed, as Mrs. Obama joins Keckley in cultivating a culture of dissemblance, she takes lessons from her younger friend, Beyoncé, who has mastered privacy in public in the era of not only the 24-hour news cycle but also social media. Besides modeling how to control access to one’s inner life, Beyoncé’s singular status and fashionista tendencies align her with both Obama and Keckley.

Mrs. Obama’s facility with securing privacy in public might be best illustrated in how Becoming engages fashion and beauty. She speaks passionately about wearing Jason Wu’s designer gown on inauguration night, insisting that it captured “the dreaminess of my family’s metamorphosis, … transforming me if not into a full-blown ballroom princess, then at least into a woman capable of climbing onto another stage. I was now FLOTUS….” Embodying that new level of capability proved especially meaningful as she and Barack attended “the Neighborhood Ball, the first inaugural ball ever to be broadly accessible and affordable to the general public and where Beyoncé—real-life Beyoncé—sang….”

Acknowledging the meaning-making power of clothing beyond inauguration night, Obama’s memoir grapples with the dilemma American culture would not let her escape: “As a Black woman, too, I knew I’d be criticized if I was perceived as being showy and high end, and I’d be criticized also if I was too casual.” Meanwhile, the memoir says close to nothing about the tensions that always arise around African American hair.

Obama’s memoir grapples with the dilemma American culture would not let her escape.

Allow me to paint a portrait of a Black woman who is creating privacy in public. She shares her life story with a nation eagerly awaiting it, and a world that will soon make it the bestselling memoir in history, and she has accepted help from a ghostwriter, adding distance between herself and the page. Even more telling, the depth of discussion about her tresses amounts to: “When I decided to get bangs cut into my hair, my staff would feel the need to first run the idea past Barack’s staff, just to make sure there wouldn’t be a problem.”

What could be more relevant than hair, especially Black hair, when engaging the politics and power of fashion and beauty? When Mrs. Obama was interviewed by Phoebe Robinson and Jessica Williams for their podcast 2 Dope Queens, the hosts gushed about how good she looked. She returned the compliments, saying “you got your hair games on!” and that was just the beginning of the conversation. As I demonstrate in From Slave Cabins to the White House, Mrs. Obama’s hair choices did a lot of (unspoken) work not only in navigating white hostility, including comparisons to men and monkeys, but also in actively affirming Black women. The full meaning and complexity will remain unspoken, but Mrs. Obama offered a hint when interacting with Robinson and Williams: “There’s a whole other life to Black hair, Black wardrobe in the public eye.”

Please notice that hair is on par with wardrobe here. So, minimizing decisions about how to wear her hair had been deliberate, as deliberate as Keckley’s single paragraph about her son’s death. Most people failed to notice, but I could feel the pride emanating from the ancestral realm as Michelle Obama’s forerunner Elizabeth Keckley nodded in approval. And that’s to say nothing of the joy in this realm as Mrs. Obama’s friend Beyoncé did, too.