Lit Mags

The First Summer

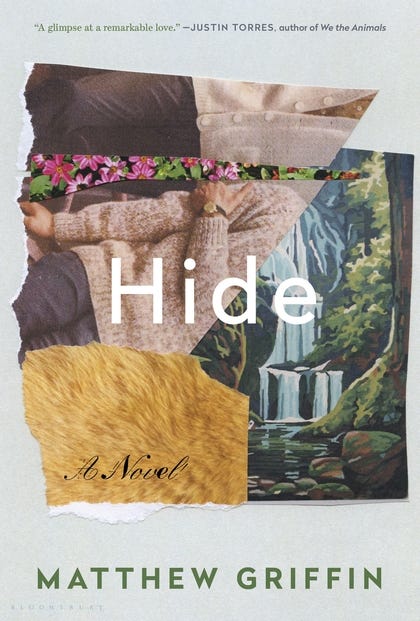

by Matthew Griffin, recommended by Stuart Nadler

AN INTRODUCTION BY STUART NADLER

There is a moment early in Matthew Griffin’s extraordinary debut novel Hide when the double-meaning of the title becomes unforgettably, heartbreakingly clear. Frank Clifton, just home from World War II, has come to Wendell Wilson’s taxidermy shop for the first time. On the table is “a whitetail buck some yokel had driven over with his car.” This is North Carolina, a faded mill town. We know already that Frank and Wendell will spend decades together in a house far off in the country that they build themselves. But still, this moment, Wendell and Frank’s first moment, full as it is with the nervousness that accompanies all first blushes of intimacy, leaps off the page. That this moment occurs between two men and that the year is somewhere around 1946 is not unimportant. Here, Wendell thinks, “I had to be sure, absolutely sure. I knew, by then, what happened when you weren’t.” Later, Wendell takes Frank’s hand and slides it beneath the skin of the deer and into the body. “I thought it would tell him,” Wendell says, “all the things I couldn’t say…”

It is exhausting to have to write that fiction like this should not feel as brave and important and transgressive as Matthew Griffin’s Hide feels, and that an honest, emotionally complicated, lushly beautiful depiction of two men who have spent their life together, and who are about to encounter death, should not feel so refreshing and so necessary. But the times, sadly, do not always dictate our literature. So, along comes a book like Hide — a first novel, a Southern novel, a novel about love and death and the terror of discovery — that does what all the best fiction seeks to do, which is that it shows its characters as humans.

In the chapter that appears here, Wendell and Frank sleep in the same bed for the first time. Such a simple, beautiful thing. And Griffin writes it that way. But there is a tinge here of something else. It’s a sense of relief. Finally, this sentence, this book, seems to say. Finally.

Stuart Nadler

Author of The Inseparables

The First Summer

Matthew Griffin

Share article

Excerpted from “Hide” by Matthew Griffin, Recommended by Stuart Nadler

We went to the beach together the end of that first summer, stayed in a little two-room shack with plywood walls so flimsy the sea breeze would have knocked them down on top of us if there weren’t so many gaps between the boards for it to slip through instead of strain against. We slept for the first time in the same bed, so narrow he crushed me against the wall and had to peel his chest from my sweaty back just to roll over, but I rested better than I had in years. I loved how deeply he breathed in the night, how early and suddenly he rose in the morning, as though sleep were a thin covering you could throw back as easily as the sheets. I loved how he had to stoop every time he walked through a door.

He cooked breakfast, humming as he pushed scrambled eggs around a dented skillet on the hot plate and waited for the last gleaming bits of moisture to burn away, while I summoned the will to get up. Even at my happiest, it always took me a long time lying in the bed, half-awake, to convince myself the world was worth waking into. He had the loveliest voice, though, could have been a singer if he’d wanted. Every note sounded like a deep laugh.

“I didn’t know you could cook,” I said, when the pop and sizzle and smell of bacon frying finally pulled me shuffling to the worn wood bench at the dining table. It barely fit between the walls. We had to climb over it to get from one side to the other.

“This is it,” he said. “Bacon, eggs, and toast. Don’t expect nothing else.” He’d learned it in the army. He was in his swim trunks already, and a white undershirt with yellow sweat stains creeping from the armpits. He scraped the eggs and bacon onto my plate and pressed two slices of bread into the greasy pan. Nothing I’ve ever cooked, in all these years, has ever tasted as good.

Afterwards, we walked through loose, hot sand that fell away from our feet and pulled us into lurching, uneven steps, down to where the waves solidified it into wet silt that held us up and held, for a few moments, the shape of our footprints. It was early still, maybe ten o’clock, and the light was hazy and soft, broken on the waves and blurred with salt. The breeze blew the loose sand in tumbling swirls toward our legs, then away, knotting together and blowing apart. There wasn’t hardly anyone else on the beach, just clumps of families so far away they could have been piles of driftwood, or heaps of seaweed. They may have been. Realtors had only built the rickety bridge to the island a couple years earlier, and there was just the one ramshackle motel then, and some falling-down shanties like ours tucked into the dunes for solitary fishermen.

We took each other’s pictures with the camera I’d bought to photograph my mounts for a newspaper ad. In them, he’s standing with his hands on his hips like he’s surveying the shore and not particularly pleased with what he sees, his brow jutted low to drape both his squinting eyes in shadow, the corrugated sea hammered out behind him. Just from the walk down to the water, he’s already drenched in sweat, his shirt hanging in heavy folds, his hair stringy and flat with it. His bare legs are huge, his calves almost as thick as his thighs.

He tugged his shirt over his head and grabbed my hand, pulled me toward the water. His palm felt rough and smooth at the same time, like sandpaper caked with the dust it’s ground away from wood, and his cheeks and shoulders and chest were sunburnt bright pink now, with dead skin peeling away in thin, papery scraps.

“You go on,” I said, taking his shirt.

“You can’t swim?”

“I can swim,” I said. “I don’t.”

“Come on,” he said. “It’s no fun by yourself.”

“I don’t trust water I can’t see my feet through.”

He looked mighty disappointed.

I watched him wade out past the sandbar, where the waves crashed and foamed, until the ocean covered his shoulders and its rolling surface sometimes obscured him completely from view before it sank again toward the earth, and there he spread his arms, lay on his back, and floated as though a lighter man had never been born. I could hardly believe somebody of his size could float so effortlessly: palms upturned to the sun, head leaned back as on a cushion, legs lounging just beneath the water with their upturned toes breaking through it to point at the sky.

I sat just beyond the water’s reach and wriggled my fingers and toes into the wet, gleaming sand at the furthest edge of a just-receded wave. I scooped up fistfuls of it, let it run between my fingers and over the edges of my hand. When I opened my fist and spread it wide, the sand cupped inside it broke open along the lines of my palm.

Frank waved at me as if I was an old friend he hadn’t seen in years and couldn’t believe his incredible fortune to come upon here, in this very place, his tattoos warping with the movements of his muscles like the shadow of a shifting cloud upon his skin. The waves built up and passed beneath him. Sometimes the water ran across and pooled in the hollow between his chest and stomach, but it never could push him under. I understood, then, how he made it to shore while all those other boys drowned, and I waved back, the wet sand trickling down my forearm, hardening as it dried into grainy, translucent rivulets that cracked and fell away. A wave spread itself across the shore as thin as it could without disappearing, then gathered itself up as it slipped backwards beneath the next, which unfurled forward and over it, as though the two were actually separate bodies, instead of twin fibers of the same heaving muscle. I marveled at that, how a single thing could move both forwards and backwards, in two directions at once.

You could do anything you wanted, I thought then. Anything at all.

He walked dripping out of the water. It poured off him in streams that ran back into the ocean, where they gave up their edges and shape and became again indistinguishable, as if they’d never pressed against him. Sea foam clung to his ribs and knees before dissolving in the wind. He sat heavily beside me in the sand and kissed me, his wet lips salty, the hair on his legs burning gold in the sun. Its light fell full and hard down on him, burned away another layer of his skin. I loved to touch those tender, sunburnt spots: how he tensed against the twinge of pain, how my white fingerprints on his chest filled back in with red.

We’re not together in any of the photographs. It was reckless enough just to walk out in the open and the sun like that without going and asking some stranger, who might not turn out to be one after all when you got close enough, to take our picture. But we’ve still got all of them, in a cedar box at the top of the closet, with his medals from the war and his mama’s wedding rings, and as tenuously as they link us, they’re the only real evidence that any of it ever happened, that we were ever even in the same vicinity. The rest we got rid of, if it ever existed at all. We never wrote each other love letters, anything someone might find, and he never came to my shop at the same time two days in a row, or by the same path through the downtown streets and alleys. Once I went to throw some carcasses in the trash can out back — the big noticeable ones I had to haul off myself, but the smaller ones, squirrels and possums and owls, I tossed in the trash can and nobody was the wiser — only to find him crawling on hand and knee down the alley to stay below the line of sight of some poor tenement family eating their gruel in the window above.

“So nobody can establish a pattern,” he said, real gruff and clipped, looking up at me from the ground.

He was the most worried about his mama. He was the only one she had left, after all — his older brother Harvey and his baby sister Iris had both died from consumption when he was a boy. It’s strange, now, to think about how many and often people died when we were children. It was happening all the time. Everybody had brothers and sisters, more than one, usually, who never saw their tenth birthday. So many people survive these days. Everybody lives so awfully long.

She was always trying to send him courting some girl she’d just met, and talking about how empty that old house felt, and how she sure would like to have some grandchildren someday to fill it back up. She was supposedly not in the best of health, had dizzy spells and heart palpitations and ‘the vapors,’ she called it. I was never convinced that was anything but a ploy to keep his attention.

But I didn’t blame him. For protecting her, for protecting himself. He’d lost enough already, felt enough pain. I didn’t want him to know how it felt to fumble for an excuse, to stammer and redden and try to explain without explaining the compromised position in which he’d been found; I didn’t want him to see the change in his mother’s eyes as the stain of understanding spread through them, seeping back through every memory and forward into every hope, so that no matter which way she looked, every sight of him was tinged with filth and soaked in sorrow.

I’d never met her, never even seen her from afar, but I felt her pull on us all the time, every minute we were together, even lying there on the beach in the hot sun. It wasn’t something we argued or even talked about, but a fundamental underlying force, like all forces invisible, that shaped our every surge toward each other and our every drifting apart, as if she was some enormous, distant mass so far away you couldn’t see it but so heavy and dense it warped all the space around it, curved it so sharp that by seven, seven-thirty every night, he started to look down at his feet, and out the window at the darkening sky, and every straight line I tried to pull him along into the hot night, no matter how fast and sure, bent into an arc that carried him back to her in time for dinner at eight. And so the closest any of those pictures come to showing the two of us together is my blurred fingertip, creeping in at the edge of one of them like the first dark sliver of the moon, invisible in the bright sky until just that moment, beginning to pass across the sun.

A storm blew up that night, a pretty bad one out of the east. I could feel it building all afternoon, slowly knotting the air into a bruise out over the waves, the ocean turning back on themselves the river waters that were supposed to run into it, and as the sun set Frank sat in the worn rocking chair out on the sagging front stoop of the shack, smelling like salt and sand, his hair ruffled with it — I loved the way his hair smelled when we came in from the beach, never wanted him to shower — and with his clasped hands pressed to his lips watched the storm clouds muscle their way through the drowsy evening light. He was always real funny about the weather. He wouldn’t take a shower during a storm, wouldn’t even wash his hands, thought the lightning would travel through the pipes and pour out the tap, crackle pink and branching all over him. His mama and her people had taken some kind of religiously-inspired pioneer trek to the Midwest when she was a girl, before they ran into a pack of unneighborly Indians and some mild cyclones and retreated back to God’s Country, having decided that they’d misinterpreted the previous signs and that it was, in fact, His Country after all. When he was a boy, she made them all huddle in the closet any time she heard a rumble of thunder. He was always watching the sky, even on the brightest of days, waiting for clouds to curdle green.

I pulled him inside, and we sat in our swimsuits on either side of the table and played gin rummy while the clouds scraped across the stars. He stretched his legs under the table and propped his feet on my lap, cold as the other side of the pillow when I flipped it in the night. When I got hot, I held them to my chest to cool me down. I pressed their soles to my cheek.

Each individual drop of rain resounded on the tin roof, sounded like someone dumping an endless truckload of gravel down on top of us, and thunder rattled the window glass. The little shack shuddered and swayed. You could feel the wind itself every now and then, big whistling gusts blowing right between the boards. I was just a turn or two away from laying my whole hand on the table in victory, when suddenly he set his cards to the side and his feet on the floor and wiped his sweaty hands on his bare thighs.

“Let’s stop,” he said.

“Stop what?”

“This game,” he said, amazed that I could even consider such an activity at such a time. “We’ll probably need to make a run for it.”

I couldn’t help laughing. He looked highly insulted.

“A run for what?” I said.

“For anywhere but inside this rickety damn house. Before it falls in on us.”

I loved to hear him curse. He was always so wholesome.

“It’s just a storm,” I said.

“Just a storm? The whole house is swaying back and forth.”

“It’s supposed to sway,” I said. “It’s on little stilts.”

“It’s going to collapse.”

“It sways so it won’t collapse. That’s the whole point of the swaying. And even if it did collapse, these boards are so flimsy it probably wouldn’t hurt.”

“We ought to evacuate,” he said.

I laughed and clambered over the table, to the one window that looked toward the ocean. Rain ran down the glass; the clouds billowed and crumbled. Light peeled them back from a bright crack in the sky, as if day were breaking through night, before darkness closed over and sealed the wound.

“Get back from there.” His voice was high and strained. “Didn’t anybody ever teach you to stay away from windows during a storm?”

I loved his nervousness, I loved his fear. I loved the way his bare foot bounced nervously on the floor, as if barely restrained from running away.

“Come here,” I said. He shook his head. “I don’t know how you ever made it through a war like this.” And, as if being dragged by an invisible, overpowering force against his will, he took the two steps from the table to the wall.

He wrapped his arms around me from behind, rested his chin in my hair. “My mother would kill me,” he said, “if she knew I was exposing myself to the elements like this.”

“You sound like somebody’s mother right about now,” I said.

He squeezed me tight against him. Sand, caught in the hair on his chest, ground against my back.

Rain dripped through a leak in the ceiling and onto the table. The roar of the wind was indistinguishable from the roar of the waves, as if they were crashing against the walls, closing over the roof. It blew through the room in a cool current. The floor shook.

“This house is about to come apart,” he said.

Lightning ripped the clouds open and sewed the clouds shut. I leaned us against the sill, so he could feel the wind: how it passed through the boards of the house and between our bodies and kept on its way, how the storm moved right through us without disturbing a thing.