Lit Mags

The Knowers

A short story by Helen Phillips, recommended by Electric Literature

Introduction by Benjamin Samuel

Despite my misanthropic tendencies, I have to concede that humans are damned remarkable creatures. We’re thoughtful, perplexing beings that create majestic works of art, painstakingly preserve them in museums housed in spectacular cities that will one day be violently reduced to dust. We sacks of meat and bone are smart enough to be aware of our own mortality, foolish enough to think we can forestall its arrival, and clever enough to devise ways to ignore this ultimate knowledge. It’s this great human paradox that forms the backbone of Helen Phillips’ “The Knowers,” a story set in a world where people may choose to learn the date — although not the circumstance — of their own demise.

In a sense, we’re either thinking about death or we’re ignoring it; death is always, even if subconsciously, on our minds — like a tattoo upon the brain, as Phillips puts it. In the world of “The Knowers” people have the choice to make that pervasive ticking clock tick just a little louder. The information is not prophecy, it doesn’t come from an oracle or the supernatural, but a machine that appears as humdrum as an ATM. Reminiscent of Kurt Vonnegut’s story “2 B R 0 2 B,” in which human’s are invincible until they volunteer to die, death — or at least its arrival — is a little less mysterious thanks to the macabre triumphs of science. But unlike Vonnegut’s story, Phillips’ characters have not defeated death, they’ve only spoiled the surprise.

The narrator of “The Knowers” is both empowered and burdened by the revelation of her doomsday: the monumental date is delivered on a scrap of paper easily destroyed but impossible to forget. Every moment is informed — clouded or enlivened — by that date, “I regretted knowing,” she says. “I was grateful to know.”

But that’s how it is for all of us. We see friends at funerals, and we’re grateful for the reminder to appreciate the time we have together. We don’t need some ghoulish Paul Revere to tell us that death is coming. We know. Life is a countdown and we find ways to occupy ourselves and forget until we’re forced to remember — like a morbid game of peekaboo. There are the “silly little band-aids” of ice cream, and television, and seaside vacations. And then there’s those little domestic tragedies, like a toothbrush falling into a toilet — that they feel like any kind of tragedy at all is, actually, pretty miraculous.

Literature, and all great art for that matter, isn’t just another band-aid, another distraction. Literature is a meaningful way to keep occupied, especially when it asks us to confront difficult questions. And here Helen Phillips has given us something worth spending time with, however much happens to remain.

—Benjamin Samuel

Co-Editor, Electric Literature

The Knowers

Helen Phillips

Share article

“The Knowers” by Helen Phillips

There are those who wish to know, and there are those who don’t wish to know. At first Tem made fun of me in that condescending way of his (a flick of my nipple, a grape tossed at my nose) when I claimed to be among the former; when he realized I meant it, he grew anxious, and when he realized I really did mean it, his anxiety morphed into terror.

“Why?” he demanded tearfully in the middle of the night. “Why why why?”

I couldn’t answer. I had no answer.

“This isn’t only about you, you know,” he scolded. “It affects me too. Hell, maybe it affects me more than it affects you. I don’t want to sit around for a bunch of decades awaiting the worst day of my life.”

Touched, I reached out to squeeze his hand in the dark. Grudgingly, he squeezed back. I would have preferred to be like Tem, of course I would have! If only I could have known it was possible to know and still have been fine with ignorance. But now that the technology had been mastered, the knowledge was available to every citizen for a nominal fee.

Tem stood in the doorway as I buttoned the blue wool coat he’d given me for, I think, our four-year anniversary a couple years back.

“I don’t want to know where you’re going,” he said. He glared.

“Fine,” I said, matter-of-factly checking my purse for my keys, my eye-drops. “I won’t tell you.”

“I forbid you to leave this apartment,” he said.

“Oh honey,” I sighed. I did feel bad. “That’s just not in your character.”

With a tremor, he fell away from the doorway to let me pass. He slouched against the wall, arms crossed, staring at me, his eyes wet and so very dark. Splendid Tem.

After I stepped out, I heard the deadbolt sliding into place.

“So?” Tem said when I unlocked the deadbolt, stepped back inside. He was standing right there in the hallway, his eyes darker than ever, his slouch more pronounced. I was willing to believe he hadn’t moved in the 127 minutes I’d been gone.

“So,” I replied forcefully. I was shaken, I’ll admit it, but I refused to shake him with my shakenness.

“You …?” He mouthed the question more than spoke it.

I nodded curtly. No way was I going to tell him about the bureaucratic office with its pale yellow walls that either smelled like urine or brought it so strongly to mind that one’s own associations created the odor. It never ceases to amaze me that, even as our country forges into the future with ever more bedazzling devices and technologies, the archaic infrastructure rots away beneath our feet, the pavement and the rails, the schools and the DMV. In any case: Tem would not know, today or ever, about the place I’d gone, about the humming machine that looked like a low-budge ATM (could they really do no better?), about the chilly metal buttons of the keypad into which I punched my social security number after waiting in line for over forty-five minutes behind other soon-to-be Knowers. There was a silent, grim camaraderie among us; surely I was not the only one who felt it. Yet carefully, deliberately, desperately, I avoided looking at their faces as they stepped away from the machine and exited the room. Grief, relief — I didn’t want to know. I had to do what I’d come to do. And what did my face look like, I wonder, as I glanced down at the paper the slot spat out at me, as I folded it up and stepped away from the machine?

Tem held his hand out, his fingers spread wide, his palm quivering but receptive.

“Okay, lay it on me,” he said. The words were light, almost jovial, but I could tell they were the five hardest words he’d ever uttered. I swore to never again accuse Tem of being less than courageous. And I applauded myself for going straight from the bureaucratic office to the canal, for standing there above the sickly greenish water, for glancing once more at the piece of paper, for tearing it into as many scraps as possible though it was essentially a scrap to begin with, for dropping it into the factory-scented breeze. I’d thought it was the right thing to do, and now I knew it was. Tem should not have to live under the same roof with that piece of paper.

“I don’t have it,” I said brightly.

“You don’t?” he gasped, suspended between joy and confusion. “You mean you changed your — ”

Poor Tem.

“I got it,” I said, before he could go too far down that road. “I got it, and then I got rid of it.”

He stared at me, waiting.

“I mean, after memorizing it, of course.”

I watched him deflate.

“Fuck you,” he said. “I’m sorry, but fuck you.”

“Yeah,” I said sympathetically. “I know.”

“You do know!” he raged, seizing upon the word. “You know! You know!”

He was thrashing about, he was so pissed, he was grabbing me, he was weeping, he half-collapsed upon me. I navigated us down the hallway to the old couch.

When he finally quieted, he was different. Maybe different than he’d ever been.

“Tell me,” he calmly commanded. His voice just at the threshold of my hearing.

“Are you sure?” I said. My voice sounded too loud, too hard. In that moment I found myself, my insistence on knowing, profoundly annoying. I despised myself as part of Tem surely despised me then. Suddenly it seemed quite likely that I’d made a catastrophic error. The kind of error that could ruin the rest of my life.

Tem nodded, gazed evenly at me.

I became wildly scared; I who’d so boldly sought knowledge now did not even dare give voice to a date.

Tem nodded again, controlled, miserable. It was my responsibility to inform him.

“April 17 — ” I began.

But Tem shrieked before I could finish. “Stop!” he cried, shoving his fingers into his ears, his calmness vanished. “Stop stop stop stop! Never mind! I don’t want to know! Don’t! Don’t don’t don’t!”

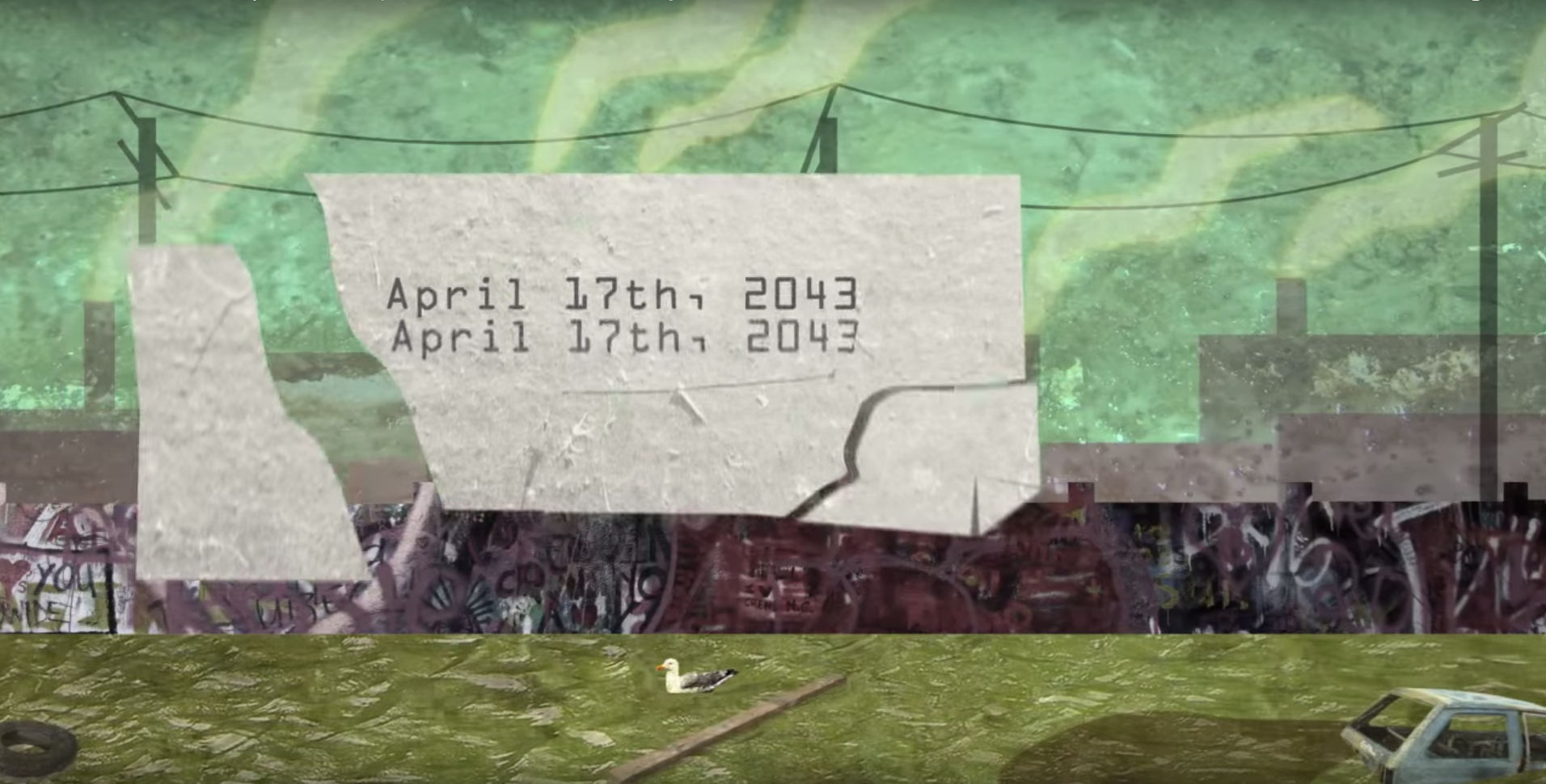

“OKAY!” I screamed, loud enough that he could hear it through his fingers. It was lonely — ever so lonely — to hold this knowledge alone. April 17, 2043: a tattoo inside my brain. But it was as it should be. It was the choice I had made. Tem wished to be spared, and spare him I would.

It was an okay lifespan. Not enough — is it ever enough? — but enough to have a life; enough to work a job, to raise children, perhaps to meet a grandchild or two. Certainly abbreviated, though; shorter than average; too short, yes; but not tragically short.

And so in many ways I could live a life like any other. Like Tem’s. I could go blithely along, indulging my petty concerns, lacking perspective, frequently forgetting I wasn’t immortal. Yet it would be a lie if I said a single day passed without me thinking about April 17, 2043.

In those early years, I’d sink into a black mood come mid-April. I’d lie in bed for a couple of days, clinging to the sheets, my heart a big swollen wound. Tem would bring me cereal, tea. But after the kids were born I had no time for such self-indulgence, and I began to mark April 17 in smaller, kinder ways. Would buy myself a tiny gift, a bar of dark chocolate or a clutch of daffodils. As time went on, I permitted myself slightly more elaborate gestures — a new dress, an afternoon champagne at some hushed bar. I always felt extravagant on April 17; I’d leave a tip of twenty-five percent, hand out a five-dollar bill to any vagrant who happened to cross my path. You can’t take it with you and all that.

Tem tried hard to forget what he’d heard, but every time April 17 came around again, I could feel his awareness of it, a slight buzz in the way he looked at me, tenderness and fury rolled up in one. “Oh,” he’d say, staring hard at the daffodils (their stems already weakening) as I stepped through the door. “That.”

I’d make a reservation for us at a fancy restaurant; I’d schedule a weekend getaway. Luxuries we spent the whole rest of the year carefully avoiding. Meanwhile, my birthday languished unnoticed in July.

Tem would sigh and pack his overnight case. We sat drinking coffee in rocking chairs on the front porch of a bed-and-breakfast on a hill in the chill of early spring. Tem was generous to me; it was his least favorite day of the year, but he managed to pretend; we’d stroll. We’d eat ice cream. The silly little band-aids.

My life would seem normal — bland, really — to an outside observer, but I tell you that for me it has been rich, layered and rich. I realize that it just looks like 2.2 children, a bureaucratic job and a long marriage, an average number of blessings and curses, but there have been so many moments, almost an infinity of moments — soaping up the kids’ hair when they were tiny, walking from the parking lot to the office on a bird-studded Friday morning, smelling the back of Tem’s neck in the middle of the night. What can I say. I don’t mean to be sentimental, but these are not small things. As the cliché of our time goes, The deeper that sorrow carves into your being, the more joy you can contain. This is no time to go into the ups and downs, the stillbirths and the car accident and the estrangement and what happened to my brother, but I will say that I believe the above statement to be true.

April 17. I’d lived that date thirty-one times already before I learned about April 17, 2043. Isn’t it macabre to know that we’ve lived the date of our death many times, passing by it each year as the calendar turns? And doesn’t it perhaps deflate that horror just a bit to take the mystery out of it, to actually know, to not have every date bear the heavy possibility of someday being the date of one’s death?

I do not know the answer to this question.

April 17, 2043. The knowledge heightened my life. The knowledge burdened my life. I regretted knowing. I was grateful to know.

I’ve never been the type to bungee jump or skydive, yet in many small ways I lived more courageously than others. More courageously than Tem, for instance. I knew when to fear death, yes, but that also meant I knew when not to fear it. I’d gone to the grocery store during times of quarantine. I’d volunteered at the hospital, driven in blizzards, ridden roller coasters so rickety Tem wouldn’t let the kids on them.

But I have to admit that December 31, 2042, was a fearful day for me.

“Are you okay?” Tem said after the kids had gone home. We’d hosted everyone for a last supper of the year, both children and their spouses, and our son’s six-month-old, our first grandchild, bright as a brand-new penny. At the dinner table, our radiant daughter and her bashful husband announced that they were expecting in August. Amid the raucous cheers and exclamations, no one noticed that I wasn’t cheering or exclaiming. The child I’d miss by four months. The ache was vast, vast. I couldn’t speak. I watched them, their hugs and high-fives, as though from behind a glass wall.

“Oh god, Ellie,” Tem said painfully, sinking onto the couch in the dark living room. “Oh god.”

“No,” I lied, joining him on the couch. “Not this year.”

Tem embraced me so warmly, with such relief, that I felt cruel. I couldn’t bear myself. I stood up and, unsteady with dread, limped toward the bathroom.

“Ellie?” he said. “You’re limping?”

“My foot fell asleep,” I lied again, yanking the door shut behind me.

I stood there in the bathroom, hunched over the sink, clinging to the sink, staring at my face in the mirror until it no longer felt like my face. This would develop into a distasteful and disorienting but addictive habit over the course of the next three and a half months.

Aside from the increasing frequency with which I found myself falling into myself in the bathroom mirror, I got pretty good at hiding my dread. From Tem, and even at times from myself. We planted bulbs; we bought a cooler for summer picnics. I pretended and pretended; it felt nice to pretend.

Yet when Tem asked, on April 10, what I’d planned for this year’s getaway, the veil fell away. Given the circumstance, I had — of course — neglected to make any plans for the 17th. The dread rushed outward from my gut until my entire body was hot and cold.

Panicking, I looked across the table at Tem, who was gazing at me openly, hopefully, boyishly, the way he’d looked at me for almost four decades. Tem and I — we’ve been so lucky in love.

“Tem,” I choked.

“You okay?” he said.

And then he realized.

“Damn it, Ellie!” he yelled. “Why’d you have to — !”

I still didn’t know, just as I hadn’t known way back then.

I quietly quit my job, handed in the paperwork, and Tem took the week off, and we spent every minute together and invited the blissfully ignorant kids out for brunch (I clutched the baby, forced her to stay in my lap even as she tried to wiggle and whine her way out, until eventually I had to hand her over to her mother, a chunk of my heart squirming away from me). Everything I saw — a gas station, a tree, a flagpole — I thought how it would go on existing, just the same. Tem and I had more sex than we’d had in the previous twelve months combined. Briefly I hung suspended and immortal in orgasm, and a few times, lying sun-stroked in bed in the late afternoon, felt infinite. What can I say, what did we do? We held hands under the covers. We made fettuccine alfredo and, cleaning the kitchen, listened to our favorite radio show. I dried the dishes with a green dishcloth, warm and damp.

On the morning of April 17, 2043, I was half-amazed to open my eyes to the light. Six hours and four minutes into the day, and I was alive. Petrified, scared to move even a muscle, I wondered how death would come for me. I supposed I’d been hoping it would come mercifully, in the soft sleep of early morning. I turned to Tem, who wasn’t in bed beside me.

“Tem!” I screamed.

He was in the doorway before I’d reached the “m,” his face stricken.

“Tem,” I said plaintively, joyously. He looked so good to me, standing there holding two coffee mugs, his ancient baby-blue robe.

“I thought you were dying!” he exclaimed.

I thought you were dying. It sounded like a figure of speech. But he meant it so literally, so very literally, that I gave a short sharp laugh.

Would it be a heart attack, a stroke, a tumble down the basement stairs? I had the inclination to stay in bed resting my head on Tem, see if I might somehow sneak through the day, but by 10 a.m. I was still alive and feeling antsy, bold. Why lie here whimpering when it was coming for me no matter what?

“Let’s go out,” I said.

Tem looked at me doubtfully.

“It’s not like I’m sick or anything.” I threw the sheets aside, stood up, pulled on my old comfy jeans.

The outside seemed more dangerous — there it could be a falling branch, a malfunctioning crane, a truck raring up onto the sidewalk. But it could just as easily catch me at home — misplaced rat poison, a chunk of meat lodged in my throat, a slick bathtub.

“Okay,” I said as I stepped out the door, Tem hesitant behind me.

We walked, looking this way and that as we went, hyperaware of everything. Vigilant. I felt like a newborn person, passing so alertly through the world. It was such an anti-death day; the crocuses. Tem kept saying these beautiful, solemn one-liners that would work well if they happened to be the last words he ever said to me, but what I really wanted to hear was throwaway words (all those thousands of times Tem had said “What?” patiently or irritably or absentmindedly when I’d mumbled something from the other room), so eventually I had to tell him to please stop.

“You’re stressing me out,” I said.

“I’m stressing you out?” Tem scoffed. But he did stop saying the solemn things. We strolled and got coffee, we strolled some more and got lunch, we sat in a park, each additional moment a small shock, we sat in another park, we got more coffee, we strolled and got dinner. Every time I caught a glimpse of us reflected in a window, I had to look again — who was that aging couple in the glass, the balding shuffling guy hanging onto the grandmother in the saggy jeans? Still, old though we’d become, my senses felt bright and young, supremely sensitive to the taste of the coffee, the color of the rising grass, the sound of kids whispering on the playground. I felt carefree and at the same time the opposite of carefree, as though I could sense the seismic activity taking place beneath the bench where we sat, gazing up at kites. Is it strange to say that this day reminded me of the first day I’d ever spent with Tem, thirty-eight years ago?

The afternoon gave way to a serene blue evening, the moon a sharp and perfect half, and we sat on our small front porch, watching cars glide down our street. At times the air buzzed with invisible threat, and at times it just felt like air. But the instant I noticed it just felt like air, it would begin to buzz with invisible threat once more.

Come 11:45 pm, we were inside, brushing our teeth, shaking. Tem dropped his toothbrush in the toilet. I grabbed it out for him. Would I simply collapse onto the floor, or would it be a burglar with a weapon?

What if there had been an error? Remembering back to that humble machine, that thin scrap of paper, the cold buttons of the keypad, I indulged in the fantasy I’d avoided over the years. It suddenly seemed possible that I’d punched my social in wrong, one digit off. Or that there had been some kind of bureaucratic mistake, some malfunction deep within the machine. Or perhaps I’d mixed up the digits — April 13, 2047. If I lived beyond April 17, 2043, where would the new boundaries of my life lie?

Shakily, I washed Tem’s toothbrush in steaming hot water from the faucet; it wouldn’t be me lingering in the aisle of the drugstore, considering the potential replacements, the colors.

We stood there staring at each other in the bathroom mirror. This time I didn’t fall into my own reflection — Tem, I was looking at Tem, that’s what I was doing.

Why had it never occurred to me that it might be something that would kill Tem too?

In all of these years, truly, I had never once entertained that possibility. But it could be a meteorite, a bomb, an earthquake, a fire.

I unlocked my eyes from Tem’s reflection and grabbed the real Tem. I clung to him like I was clinging to a cliff, and he clung right back.

I counted ten tense seconds. The pulse in his neck.

“Should we — ?” I said.

“What?” Tem said quickly, almost hopefully, as though I was about to propose a solution.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Go to bed? It’s way past our bedtime.”

“Bedtime!” Tem said as though I was hilarious, though he didn’t manage a laugh.

11:54pm on April 17, 2043. We are both alive and well. Yet I mustn’t get ahead of myself. There are still six minutes remaining.