Craft

The Last Station: Gentrification, Fire and Protest in Istanbul

Burhan Sönmez Examines a City’s Changing Face

I was seventeen years old when I arrived at Haydar Pasha Station in Istanbul. I got off the train and walked down the marble steps where the Station met the sea. Instead of admiring the Station’s magnificent facade, I stared at the old city across the Bosphorus. I saw Istanbul for the first time then.

I had taken the Blue Train the night before at eleven o’clocks and reached the last stop at eight in the morning. Haydar Pasha Station was the end of the railway line on the Asian continent. There began the sea, then Europe. I came to Istanbul to study law but I was more excited with the city itself than studying at the university. It was a warm day. I could see historical buildings through a thin fog: the city walls, the roofs of Topkapi Palace, the dome of Hagia Sophia Church and the minarets of the Blue Mosque.

Whenever I recall that moment I think of what Herman Melville wrote about his visit to Istanbul in 1856. It was a few years after the publication of Moby-Dick. He was an unsuccessful writer despite his great books and was still floating from one sea to another. He wrote in his diary:

“The fog lifted from about the skirts of the city. It was a coy disclosure, a kind of coquetting, leaving room for the imagination and heightening the scene.”

I sensed on the first day that Istanbul would always embrace me with a light curtain of fog. Any time I would return to Haydar Pasha after school holidays I would meet Istanbul through that curtain. As the years roll on I now realise that my past has become more distant, the fog of my old days are denser, and the Station’s vivid times are vague.

Haydar Pasha Station was designed as the beginning point of a railway line towards Asia-minor and improved to accommodate the northern terminus of the Baghdad Railway line in 1904. Because of increased traffic, a larger building was needed, and two German architects, Otto Ritter and Helmut Conu, were appointed to carry out the job. They chose a neo-classical style to build the new station. The origin of the Station’s name is not certain but it is assumed that it was given in honor of a high ranking Ottoman officer, Haydar Pasha, who had served to the Sultan Selim III.

It is rather a gate opening to a great city than a mere station. As you come out of it you see a few steps going down to the pier where a ferry takes you to the city. It is the spot where Istanbul and the rest of the country unite. Trains carry people from small towns in the provinces to that picturesque spot by the Bosphorus.

The poetry book of Human Landscapes From My Country by Nazım Hikmet begins there, in front of the Station:

“Haydar Pasha Station,

spring 1941,

3 p.m.

On the steps, sun

fatigue

and confusion.

A man

stops on the steps,

thinking about something.

Thin.

Scared.”

It is not a coincidence that Nazım Hikmet picked Haydar Pasha Station for the opening of his grand book. It is a kind of verse-novel: 17,000 lines describing different people, through whom a whole picture of a country can be seen. Hikmet (1902–1963) is regarded as the greatest poet of modern Turkish literature. He began to write Human Landscapes during the Second World War, while in prison, serving a twenty-eight-year sentence for his communist beliefs. He gave the stories of the people on the train — in its cars, its restaurant, in the locomotive — and talked about their past and their dreams. He used his pen in a cinematographic way and presented the collective memory of a nation, alongside its fears and hopes, in an epic style.

If you are an author in Turkey you are destined to write about Istanbul sooner or later. I have come to that point in my third novel, Istanbul Istanbul. When I was working on it, my mother — my lifelong advisor — asked me what I was writing about. “About Istanbul,” I said. There was a pause on the other end of the telephone line. “The train station,” she said with a tender and confident voice, “you should not forget to mention the train station.” I scanned my mind to recollect what I had been covering in my novel. Writing about Istanbul required plenty of work. I had done my research, taken notes down and formed stories. But on hearing my mother’s words, I realized that I didn’t have a story taking place around Haydar Pasha Station. She, an illiterate Kurdish woman from rural Anatolia, opened a crack in my mind, as she had always done with her fairytales when I was a little child. She had fed me not only with milk but also with stories about rascal jinnies, faraway seas and invisible cities. And now she once again blew her breath into my chest and led me to put some ornaments of her mind into my novel. In Istanbul Istanbul there are some pages, like the opening story of chapter nine, written and designed in line with her wish. It is a story that takes place on the steps of Haydar Pasha Station, where helpless lovers fall in despair and at the same time find a glimpse of light. They are the same steps where Hikmet’s Human Landscapes began.

There are some cities you don’t need to see in order to fall in love with. Istanbul is one of them. I had fallen for her before I arrived at Haydar Pasha Station. I knew her through stories, novels, paintings and songs. But meeting her was not easy for a boy of seventeen like me. The speed, the enormity, the finely tuned chaos of the city was a world away from where I grew up, a small town in the middle of the plains. And the times were not easy for the people of Turkey either. There had been a military coup a couple of years before, in 1980. A heavy atmosphere was hanging over the city. Curfews, prohibitions, tortures, and book burnings were part of daily life. But despite all this, we had dreams in our hearts. We had an imagination of another way of life. We knew Istanbul was not a calm city to live in. The cost of living was high, and there were unemployment, traffic, crime, and intolerance. But it has always left room for the imagination as Herman Melville wrote: “The fog lifted… leaving room for the imagination.”

In France they say, “All poets are born in the countryside but die in Paris.” Istanbul has the same essence. Our poets and writers pen shady lines or lively scenes and indicate through them where they should be buried. Some acknowledge Istanbul as the junction of historical geographies, the meeting point of East and West. Some see it as a land of desire and mysticism and relate it to past eras. The Turkish poet Yahya Kemal, the short-story writer Sait Faik, and the novelists Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar and Orhan Pamuk have approached Istanbul from different perspectives. Each of them has created his own city, unlike the others in its literature.

When you are underground there is only one direction that matters: upwards, toward the sky.

In Istanbul Istanbul, I wanted to portray the city as the unification point of time and space and the melting pot of opposing tendencies in life. I preferred not to talk about past golden ages. That approach has already been used up in our literature. In my novel, space and time converge on a prison cell three floors underground. When you are underground there is only one direction that matters: upwards, toward the sky. Time moves differently underground. On the surface, time is linear — past and future eclipse all else, and what matters is less where are you than where you’re going. Underground, past and future mean nothing. There is only the eternal, often agonising, now. By focusing my novel on prisoners in a subterranean cell, discussing the city above, I wanted to unite time and space, hope and hopelessness, darkness and brightness. They are all together and one. Istanbul is the name of that wholeness. Wherever you were born, you come to Istanbul to be part of its wholeness.

Istanbul is too real and at the same time too ambiguous. It makes possible both good and bad. When I was in one of those interrogation cells I felt the underground was the place for evil, while aboveground seemed to be the place for good. But instead of writing about good and evil, I wanted to explore the shades between them and to show how they exchange places.

Istanbul as a metropolis is not only the heart of this country but also the future of it. The beautiful and the ugly in Istanbul reflect the future of our people. That’s why it is now also the heart of our politics.

The Conservative bodies believe in the past. They think the best days are behind us. With passed utopias before their eyes, they don’t hesitate to ruin the present. They are wiping out the city’s green areas and constructing tall buildings. They call it progress. That’s why people feel obliged to defend this city against greediness. And now the word ‘beauty’ is not only an aesthetic word but a political word, too. When people call for beauty in Istanbul, the responses they get are police, tear-gas and the rise of construction firms in the stock market.

And now the word ‘beauty’ is not only an aesthetic word but a political word, too.

In the tales of my childhood there was always a place for heroes to suffer and then emancipate. Istanbul is now the place of both suffering and emancipation in our contemporary writing. We write about Istanbul with the hope that its beauty will shape our future.

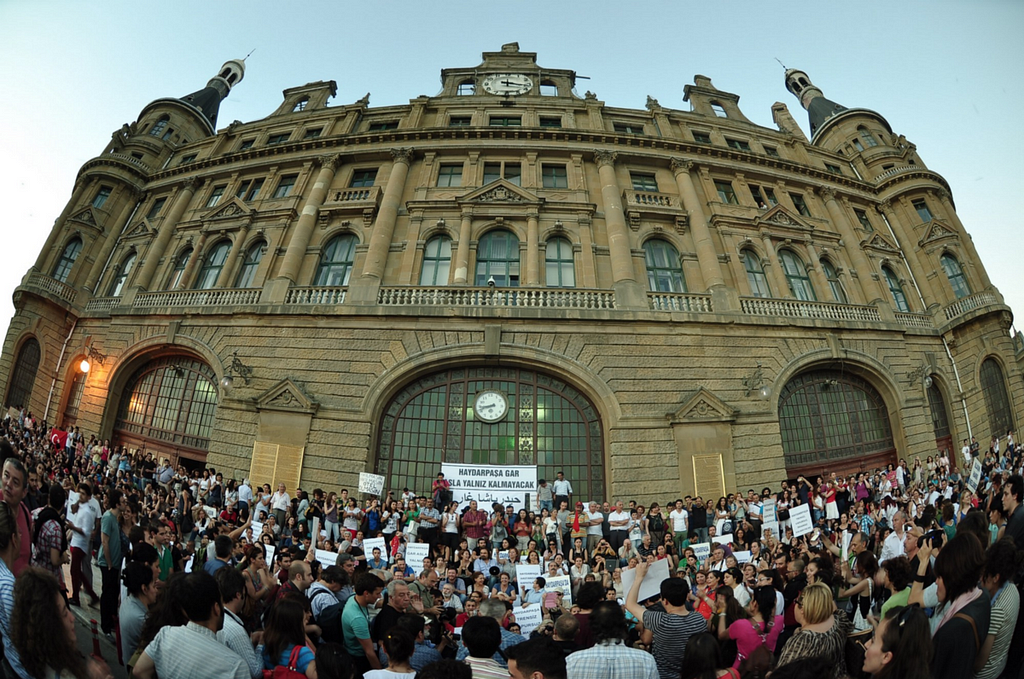

After having witnessed two world wars, the invasion of the British army and the exile of Armenian intellectuals, the Haydar Pasha Station met its latest disaster on 28 November 2010, when a fire began on top of the roof. The fire was stopped before it was too late, but following the fire the station was closed down.

It was a suspicious fire. It came about the same time as legal debates were being held regarding Haydar Pasha Station and its surroundings. The government wanted a new development in the area, turning Haydar Pasha’s castle-like building into a fancy hotel. But the public opposed it and the legislative charter for the development was suspended by the court. Various international institutions, like the New York-based World Monument Fund, have added Haydar Pasha to their agenda, emphasising the uncertain future of the railway.

Local authorities promised to renew railway lines and resume train journeys again by the end of 2015. But not a single rail line has been renewed so far, nor has there been any sign of reopening the Station. Istanbul dwellers are aware that Haydar Pasha might be another victim of urban gentrification. That’s why they have formed a new civic organization under the name “Haydar Pasha Solidarity” and launched an effort to save the Station, organizing concerts, exhibitions, and demonstrations. They also read out some lines from Human Landscapes, where Nazım Hikmet, many years ago, pointed out the merciless face of urban gentrification, which tears apart past and present:

“Concrete villas.

Lined up all the way to Pendik.

The trees are mere saplings,

the grapevines just greening.

The 3:45 train goes screaming past.

Concrete villas.

The Secretary Pasha’s summer house,

a forty-room marvel,

has been torn down.

Now it’s concrete villas,

concrete villas

all the way to Pendik.”

About the Author

Burhan Sönmez is the author of Istanbul, Istanbul (2015), Sins & Innocents (2011), and North (2009). He was born in Turkey and grew up speaking Turkish and Kurdish. He worked as a lawyer in Istanbul and was a founder of the social-activist culture organisation TAKSAV (Foundation for Social Research, Culture and Art). He has written in various newspapers and magazines on literature, culture and politics. He was seriously injured following an assault by police in Turkey and had to move to Britain to receive treatment with the support of Freedom from Torture in London. He now lives in Cambridge and Istanbul.