Recommended Reading

The Light In This Apartment is Better Without You In It

Catherine Lacey recommends ‘Territory of Light’ by Yūko Tsushima

INTRODUCTION BY CATHERINE LACEY

Seeking shelter is rarely an exercise in pure practicality. Once our barest needs are met, our homes are the way we remind ourselves who we are, or perhaps more crucially — who we believe ourselves to be. If your home ceases to be your home, it’s not just an inconvenience but a demolition of the self.

The late Japanese writer Yūko Tsushima described the narrator of her short 1979 novel, Territory of Light, as being hardly a half-step from her own life; anyone who has ever sought refuge amid precarious circumstances will  immediately recognize the warm braid of fear and hope at the heart of this book. The novel was originally published in twelve parts (each chapter measuring a month) in the Japanese monthly magazine, Gunzo, so readers could experience the novel in real time. The first chapter, excerpted here, opens with a nameless woman settling into a small but brightly lit one bedroom with her young daughter. She is pleased “for having managed to protect [her] daughter from the upheaval around her with the quantity of light.” Light provides comfort and a kind of blindness.

immediately recognize the warm braid of fear and hope at the heart of this book. The novel was originally published in twelve parts (each chapter measuring a month) in the Japanese monthly magazine, Gunzo, so readers could experience the novel in real time. The first chapter, excerpted here, opens with a nameless woman settling into a small but brightly lit one bedroom with her young daughter. She is pleased “for having managed to protect [her] daughter from the upheaval around her with the quantity of light.” Light provides comfort and a kind of blindness.

“The man who at the time was still my husband,” she tells us, had tried to insist on a larger apartment for his estranged wife and child, swearing he couldn’t sleep if she chose “some dump,” so they viewed a string of apartments together that neither of them could afford. A realtor takes her to a beautiful home priced suspiciously low. Our nameless woman finds out why, and flees. Light, like moving one’s home, also has the power to expose latent falsehoods in one’s life. A certain angle of sunset reveals all the neglected dust in a room. An over-lit mirror can expose every blemish and slack.

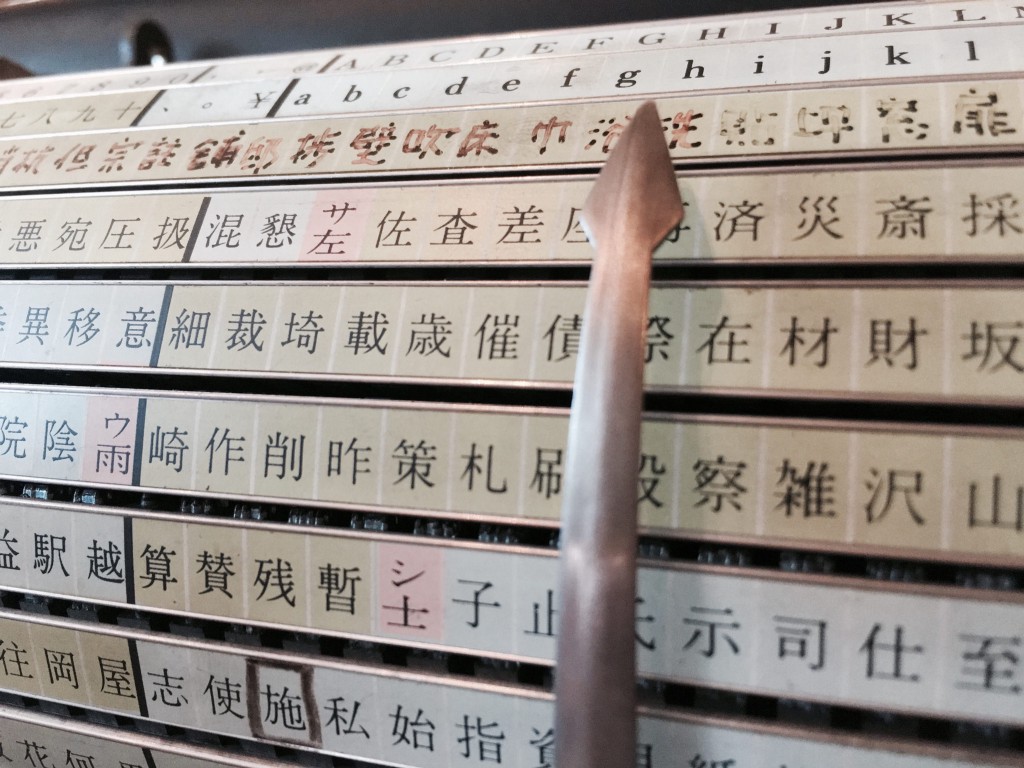

In some ways, literary translation is also a process of setting the lighting around a text. Geraldine Harcourt, who has translated many of Yūko Tsuhima’s works into English, clearly possesses all the subtlety and elegant touch of Tsushima; she wielded enormous power in her simplicity, could make waves crash in a living room. Territory of Light is as compact and multi-faceted as a diamond, a book so complete in its brevity that even on second and third readings, luminous observations continue to spill out.

Catherine Lacey

Author of The Answers

The Light In This Apartment is Better Without You In It

Yuko Tsushima

Share article

Territory of Light, excerpt

by Yūko Tsushima

The apartment had windows on all sides.

I spent a year there, with my little daughter, on the top floor of an old four-story office building. We had the whole fourth floor to ourselves, plus the rooftop terrace. At street level there was a camera store; the second and third floors were both divided into two rented offices. A couple whose small business made custom gold family crests, framed or turned into trophy shields, occupied half a floor, as did an accountant and a branch of a knitting school, but the rooms on the third floor facing the main street happened to remain vacant all the time I lived above them. I used to slip in there some nights after my daughter had finally gone to sleep. I would open the windows a fraction and enjoy a different take on the view, or walk up and down in the empty space. I felt as if I were in a secret chamber, unknown to anyone.

I was told that until I rented the fourth-floor apartment, the building’s previous owner had lived there, and while this certainly had its perks — sole access to the rooftop and the spacious bathroom that had been built up there — it also meant that by default I was left in charge of the rooftop water tower and TV antenna, and that I had to go down late at night and lower the rolling security shutter at the stairwell entrance after the office tenants had all gone home, a task which naturally had been the owner’s.

The whole building had gone up for sale and been bought by a locally famous businesswoman by the name of Fujino. I was to become the first resident of the newly christened Fujino Building №3. The owner herself was apparently new to the residential end of things, having specialized in commercial property till now, and, unsure about an apartment with an unusual layout in a dilapidated office building, she had tentatively proposed a low rent to see if there would be any takers. This happenstance was a lucky break for me. Also quite by chance, the man who at the time was still my husband had the same name as the building. As a result, I was constantly being mistaken for the proprietor.

At the top of the steep, narrow, straight stairs there was an aluminum door and, opposite that, a door to the fire escape. The landing was so small that you had to take a step down the stairs or up on to the threshold of the fire exit before being able to open the apartment door. The fire escape was actually an iron ladder, perpendicular to the ground. In an emergency, it looked like we might stand a better chance if I bolted down the main stairs with my daughter in my arms.

But once you got the door open, the apartment was filled with light at any hour of the day. The kitchen and dining area immediately inside had a red floor, which made the aura all the brighter. Entering from the dimness of the stairwell, you practically had to squint.

‘Ooh, it’s warm! It’s pretty!’ My daughter, who was about to turn three, gave a shout the first time she was bathed in the room’s light.

‘Isn’t it cosy? The sun’s great, isn’t it?’

She ran around the dining-kitchen as she answered with a touch of pride, ‘Yes! Didn’t you know that, Mommy?’

I felt like giving myself a pat on the head for having managed to protect my daughter from the upheaval around her with the quantity of light.

The one window that caught the morning sun was in a cubbyhole beside the entrance, a kind of storage room less than two tatami mats in area. I decided to make that our bedroom. Its east-facing window overlooked platforms hung with laundry on top of the crowded neighboring houses, and the roofs of office buildings smaller than Fujino №3. Because we were in a shopping district around a station on the main loop line, not one of the houses had a garden; instead, the neighbors lined up on the platforms and rooftops all the potted plants they could lay their hands on and even set out deckchairs, so that the view from above had a very homey feeling, and I often saw elderly people out there in their bathrobe yukata.

There were south-facing windows in every one of the straight line of rooms — the two-mat, the dining-kitchen, and the six-mat. These looked over the roof of an old low house and on to a lane of bars and eateries. For a narrow lane it saw a lot of traffic, with horns constantly blaring.

To the west, at the far end of the long, thin apartment, a big window gave on to the main road; here the late sun and the street noise poured in without mercy. Directly below, one could see the black heads of pedestrians who streamed along the pavement towards the station in the morning and back again in the evening. On the sidewalk opposite, in front of a florist’s, people stood still at a bus stop. Every time a bus or truck passed by the whole fourth floor shook and the crockery rattled on the shelves. The building where I’d set up house with my daughter was on a three-way intersection — four-way counting the lane to the south. Nevertheless, several times a day, a certain conjunction of red lights and traffic flow would produce about ten seconds’ silence. I always noticed it a split second before the signals changed and the waiting cars all revved impatiently at once.

To the left of this western window were just visible the trees of a wood that belonged to a large traditional garden, the site of a former daimyo’s manor. That glimpse of greenery was precious to me. It was the centerpiece of the view from the window.

‘That? Why, that’s the Bois de Boulogne,’ I answered whenever a visitor asked. The name of the wood on the outskirts of Paris had stuck in my mind, like Bremen or Flanders, some place named in a fairy tale, and it was kind of fun just to let it trip off my tongue.

Along the northern wall of the dining-kitchen were a closet, the toilet, and the stairs to the roof. The toilet had its own window, with a view of the station and the trains. That little window was my daughter’s favorite.

‘We can see the station and the trains! And the house shakes!’ she proudly reported to her daycare teacher and friends at the start.

But she quickly came down with a fever brought on by the move and spent nearly a week in bed. While I was at work I left her with my mother, who lived alone not far away. My job, at a library attached to a radio station, was to archive broadcast-related documents and tapes, and issue them on loan. At the end of the day I stopped by my mother’s and stayed with my daughter till past nine, then returned alone to the building. My husband would no doubt have helped out if I’d contacted him, but I didn’t want to rely on my husband, even if it meant putting my mother to extra trouble. In fact, I didn’t want him ever to set foot in my new life. I was afraid of any renewed contact, so afraid it left me surprised at myself. The frightening thing was how accustomed I had become to his being there.

Before he left, he had been urging me to move back to my mother’s. ‘She must be lonesome, and besides, how are you going to manage with the little one on your own? With you two at your mom’s, I could leave you without worrying.’

He had already chosen an apartment for himself along a suburban commuter line. He was due to move there in a month, when the place became vacant.

As for me, at that time I hadn’t been able to get as far as thinking about where to go. His decision had yet to fully sink in. Wasn’t there still a chance I’d hear him laugh it all off as a joke tomorrow? Then why should I worry about where I was going to live?

I told him I didn’t want to go back to my mother’s. ‘Anything but that. That would just be trying to disguise the fact that you’ve left us.’

He then offered to come with me to look for an apartment. ‘If you go by yourself you’ll just get ripped off. I won’t be able to sleep at night knowing you’re in some dump. Come on, now, leave it to me.’ It was late January, and every day was bright and clear. I began doing the rounds of real estate agents with my husband. All I had to do was tag along without a word. I would meet him in my lunch hour at a café near my work and we’d go to the local agencies, one after the other.

He specified a 2DK (two rooms plus dining-kitchen), sunny, with bath, for around thirty thousand to forty thousand yen a month. The first place we tried, he was laughed at: ‘These days you won’t find anything like that for under sixty to seventy thousand.’ ‘It’s actually for her and our child,’ he said, looking back at me. ‘Any old thing would do for me, but I want them to have the best possible . . . Are you sure you don’t have something?’

The next day, exactly the same conversation took place at another agency. Unable to contain myself, I whispered, ‘The bath doesn’t matter, really. And I’d be happy with one room.’ Then I spoke up to the realtor: ‘There are studios at thirty to forty thousand, aren’t there?’

‘Studios, yes . . .’ He reached to open a ledger.

At this point my husband said sternly, as if scolding a child, ‘You’re too quick to give up. You’re going about it the wrong way. Once you’ve settled in you’ll find you can afford the rent, even if it seems a stretch right now. But you can’t fix up a cheap apartment with the cash you save, the landlords don’t allow alterations . . . So, what have you got in the fifty to sixty thousand range?’

The realtor assured us that he could show us several possibilities in the fifty thousand or, better still, the sixty thousand yen range. ‘We’d like to see them,’ said my husband. Considering he was so hard up he’d had to borrow from me to pay for the lease and security deposit on his own apartment, I could hardly expect him to provide financial support after the separation. He had been insisting that living apart was the only way out of the impasse in which he found himself — a clean sweep, a fresh start on his own. In that case, I wanted to pay my own way too and not cadge any more from my mother. The maximum rent I could afford was therefore fifty thousand yen, which was what the place where we’d been living together cost. I calculated that without my husband’s living expenses to cover, I should be able to get by without borrowing. But it was a calculation made with gritted teeth. Fifty thousand yen was more than half my monthly pay.

That day, we were shown a sixty-thousand-yen rental condominium. There was nothing not to like and it was handy for the office, but I didn’t take it.

Almost every day, we toured a variety of vacancies. We looked at a seventy-thousand-yen condominium with a garden. And a policy of no children. My husband appealed to the landlord that it was just the one child, a girl, and she’d be away all day at daycare, but I could have told him it would do no good.

The viewings were creeping steadily upmarket. I was now able to shrug off hearing a rent that amounted to my entire pay. I felt neither uneasy nor conscious of the absurdity. We were enthusiastically inspecting apartments I couldn’t possibly rent, and we were apparently dead serious. But neither my husband nor I saw ourselves as the one doing the renting. He was accompanying me, and I was accompanying him.

‘Are we going again today?’

This question had become part of our morning routine. Weather permitting, most of my lunch hours were taken up by a busy whirl. And from January into early February every day was as fine as could be.

There was a house with a Japanese cypress beside its front entrance. At the top of five stone steps, a light-blue door beckoned. The door was barely three feet from the steps; the tree had just enough room to grow. Its branches hid a bay window whose frame had been painted the same color as the front door.

‘This is quite something.’ My husband sounded excited.

‘But I don’t care for that tree. I’d rather have a magnolia, say, or a cherry . . .’

‘A cypress has way more class.’

It was a two-story house. Downstairs were a room with a wooden floor and bay windows, a six-tatami room that didn’t get much light, and a dining-kitchen; upstairs were two well-lit tatami rooms and even a place to hang out laundry. By the time we checked out the laundry deck, both my husband and I were very nearly euphoric. Aware of the agent within earshot, we said to each other, all smiles:

‘I bet your friends would be happy to come over.’

‘And there’s plenty of room for them to stay . . .’

‘It’d be a great place to bring up a child. Easy for me to drop in too . . . I’m starting to envy you, I’d like to rent it myself. I’d have my desk by that window . . .’

‘The bookshelves can go along that wall.’

‘Right . . . Hey, I know, let me be your lodger. I’ll pay room and board on the dot.’

‘Sure. But you’re not getting a discount.’

As our laughter echoed in the empty rooms, it brought a weak smile to the realtor’s lips.

I couldn’t help thinking, once again, that I was never going to have to live alone with our daughter. If I could live with my husband I didn’t care where, and without him everywhere was equally daunting.

Back at the library that day, for a while I pictured life in the two-story house. My husband had enthused, ‘Take it, don’t worry about the rent, just get your family to help you,’ and then disappeared. I would put the stereo in the room with the bay windows and use that space for meals and for relaxing. I’d make the dark six-mat room downstairs our bedroom and keep the upstairs for guests until my daughter was older. No, on second thoughts, the sunny, spacious upper floor was obviously more comfortable. I wondered who would visit, apart from my husband. Since it was close to the office, would my colleagues come if I invited them?

As I was immersed in these thoughts, a high-school teacher from out of town asked to borrow some tapes of poetry readings for classroom use. My mind still far away, I inserted the series one by one in a tape recorder. We always had borrowers listen to a part of the tapes we issued to ensure they were the right ones.

For some reason, the words on the tape suddenly registered with me.

‘Quick now, give up this idle pondering!

And let’s be off into the great wide world!

I tell you: the fool who speculates on things

is like some animal on a dry heath,

led by an evil fiend in endless circles,

while fine green pastures lie on every side.’

Startled, I asked the teacher standing there, ‘What was that?’ Could that be poetry, I was wondering. He glanced at the window, evidently thinking I’d heard something outside, then cocked his head to one side with a puzzled smile.

My husband didn’t come home that night, nor the next. He was probably convinced that my new location had been decided.

I began to go around the agencies by myself. It was the first time I’d entered a realtor’s all alone.

The voice on the tape had reminded me of my last move, four years ago. The memory had caught me by surprise.

My husband was still a grad student and I hadn’t been working long at the library. Though we each had our own apartment, half the time he spent the night at mine. I had a call from him one day at the library: ‘We have an apartment. It’s new, and quiet, and sunny. It’s fantastic. I said we’d move in on Sunday. OK?’

It had been only the night before that we’d raised the subject of needing to look for a place for the two of us.

‘That was fast. You said we’d take it?’ Though astonished, I was also delighted by the effortlessness of the decision. I was not annoyed at having had no say in where I was to live. I was enjoying the feeling of being swept along by a man. I’d left home to be free to have him stay over and he’d found the place for me that time too, a room in a student boarding house used by his friends. But it had taken him a while to make up his mind that I was the one.

All I had to do was follow his instructions. I packed on Saturday night and was ready in the morning when the truck came around after stopping at his apartment. I had so little to load, it was the work of a moment. I joined him riding in the back and we set off, me with a stack of LPs on my lap, him with a shopping bag full of laundry in his arms.

In about thirty minutes we arrived. The new place was down a cul-de-sac in a residential area.

‘Is this it?’ I exclaimed happily. It was my first sight of my own apartment.

We lived there for a year and a half, until I became pregnant. Which meant I had never even found myself a place to live before now, I realized. Bizarre though it seemed, I had to admit it was true.

I made the rounds on my own, meticulously, in the vicinity of my daughter’s daycare. Before I knew it we were into March. Inevitably, the low-rent properties I was asking to see were a far cry from those I’d toured with my husband, and I often felt like retreating in dismay. However, the more of those gloomy, cramped apartments I looked at, the further the figure of my husband receded from sight, and while the rooms were invariably dark, I began to sense a gleam in their darkness like that of an animal’s eyes. There was something there glaring back at me. Although it scared me, I wanted to approach it.

Once, offered a real bargain, a very nice 2dk unit in a condominium building for thirty thousand yen, I went dubiously to look at it. Everything about it was normal, as far as I could see.

‘But this doesn’t make sense. Why is it so cheap?’

The realtor reluctantly confessed the truth, since I was bound to find out anyhow. ‘There was a family suicide. Gas, so it’s not as if it left traces. It was said to be a murder-suicide after a divorce battle. It was in the papers. And as if that weren’t bad enough, when a couple moved in next, the wife went and hanged herself . . . Yes, hanged herself. It beats me, it really does. The place has been empty ever since. It’s been a year now.’

‘I see . . . Then it was a sort of chain reaction? She must have thought she could stay untouched by the deaths,’ I said, fighting down an urgent desire to get out of there.

‘I expect you’re right. They’ve changed the tatami and repainted the walls, but of course the gas valve is still in the same position. That’s it there.’

The realtor pointed to a corner of the smaller room. A heap of corpses met my eyes on the tatami, toppled around the outlet.

‘She couldn’t help seeing the bodies, I guess . . .’

‘She seems to have had a breakdown. She’d only just arrived from her hometown . . .’

I said I’d think about it and made my escape. ‘There’s no hurry, it won’t be snapped up,’ the agent counseled. But though I wasn’t superstitious, I wasn’t sure I could stay unaffected, either.

A few evenings later, a different realtor escorted me to a tall, thin building. From below my first reaction had been a sigh at the sight of the formidable stairs, but the minute he opened the place up and I took one step inside, I crowed to myself that this was the apartment for me. The red floor blazed in the setting sun. The long-closed, empty rooms pulsed with light.

The first cherry blossoms were coming out by the time my daughter, made ill by exhaustion after the move, was well enough to start back at daycare. I taught her ‘Sakura, Sakura’ along with ‘The Little Bleating Goat’ and the song about the crow. Our voices boomed inside the bathroom, but it felt even better to belt the songs out on the rooftop. I was impressed, I admit, to discover I had such a fine voice. I bought a supply of nursery rhyme books and sang my way through them between bursts of applause from my daughter. In the back of my mind I was listening to the words I’d heard on the tape: Give up this idle pondering.

In tears of excitement, my daughter showered me with ‘Encores’ and ‘Bravos’ she’d picked up from a picture book.

I didn’t know my husband’s new address. All I’d been given was the phone number of the restaurant where he was now working part-time. Someone had told me that his new woman friend was the owner, and that she was old enough to be his mother. She might be just what he needed, I thought, after he’d led a group of his friends in trying to start a small theatre company and ended with nothing to show for it but debts.

He hadn’t been pleased at my deciding on a new place by myself, and had moved out before me, still aggrieved. I no longer had any intention of letting him into my apartment.

He would come, though. While afraid of that moment, at the same time I was beginning to be aware that I couldn’t turn his way once again. And this after I’d been so unwilling to break up in the first place. I was puzzled by how I had changed. But I could no longer go back.

Quick now, give up this idle pondering. And let’s be off!

So I told myself. My daughter had yet to notice her father’s disappearance.

‘. . . In the summer, let’s have a paddling pool on the roof. There’s room for a big one,’ I said as I put her to bed. ‘And let’s have a couple of sun-loungers as well. I could go for a beer too. Shall we string up fairy lights like the rooftop beer gardens do? Won’t they be pretty? And let’s plant lots of flowers. Sunflowers and dahlias and cannas. Shall we keep a rabbit? A guinea pig would be nice. But actually we could keep an even bigger animal. A goat — why not? And how about chickens? That’s it, we’ll have a farm. Won’t the neighbors be surprised when the cow goes moo . . .’

My daughter was watching my mouth with wide eyes. I stroked her head.

The two-mat bedroom was as small as a closet, and I felt at home.