Books & Culture

‘The Little Prince’ Leaps Off the Page and Onto the Screen

On the film adaptation of a certain beloved French children’s book

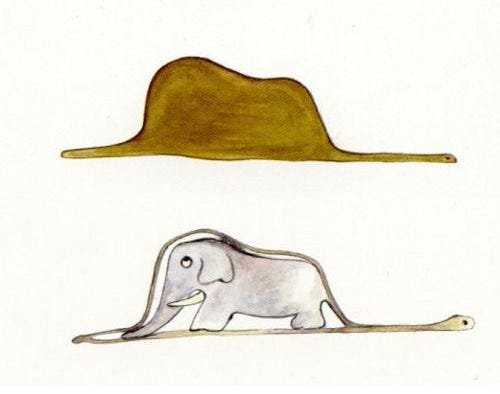

Mark Osborne’s animated adaptation of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince (2015) opens with an image all too familiar to fans of the 1943 children’s novella. Over a blank page, a voice (Jeff Bridges) tells us that as a child he saw a magnificent picture in a book, True Stories from Nature, of a boa constrictor in the act of swallowing an animal it had wrapped itself around. The illustration, reproduced from the first page of Saint-Exupéry’s book, comes to life in the film before our eyes, and is followed by the narrator’s first attempts at becoming an artist himself.

As an invisible pencil inscribes “Drawing Number One” and “Drawing Number Two,” he explains that grown-ups, odd as they are, have never quite understood his illustrations, encouraging him instead to concern himself with “matters of consequence.” It’s the reason, he says, that he became an aviator, and why he has never told the story of his friend the Little Prince to anyone. Before now, that is. As if on cue, many other illustrations from that famous French book flicker before us, setting the mood for what’s to follow.

More than that, this opening sequence promises (and quite literally delivers) what is so often expected of filmed literary adaptations: that they will present us the pages of the book brought to life, animated, in the case of The Little Prince, as if by the very spirit that so enchanted us when we first flipped through Saint-Exupéry’s book — a book in which the eponymous Little Prince, wishing for a sheep to help him ward off the baobabs threatening his small home planet, worries at the same time that it would also eat his treasured blooming flower. And yet, the moment we cozy to the idea, the film changes form into something else. Gone suddenly are the hand-drawn pictures in a throwback watercolor style, as we enter the world of 21st-century CGI.

A young girl (Mackenzie Foy) and her mother (Rachel McAdams) are in the hallway of the Werth Academy, where The Little Girl will soon face an admissions committee like something out of Kafka. Unlike the earlier hand-drawn images — near replicas of Saint-Exupéry’s illustrations, in the style of his pseudo-autobiographical narrating avatar — which evoked a vibrant texturedness and whimsy characteristic of the book, this pristine hallway with its Pixar-like characters looks outright flat and glossy. Eventually, despite her mother’s well-intentioned helicopter parenting, The Little Girl bombs the admissions exam and they move on to Plan B: purchasing a home in the neighborhood of the Academy, thereby ensuring that The Little Girl will be granted a spot there in the fall.

Adjacent to their new home they discover a rickety house, owned by an eccentric elder aviator with whom the girl develops a friendship, centered mostly around a series of stories he writes and illustrates for her. They are, of course, facsimiles of the first French edition of Le petit prince, and whenever The Little Girl reads them the audience is plunged alongside her into the narrative. To visually index the change Osborne and his animators forgo CGI, instead relying on stop-motion animation for these sequences, fleshing out, as it were, the tactility of the book’s illustrations. Not surprisingly these are the most affecting sequences in the film, beautifully rendering the simplicity of Saint-Exupéry’s story with just enough twee detail (stars that literally hang from a thread, a rose made more exquisite by its emphasized paper-like appearance, character design that is stridently minimalist) to warrant the leap from still to moving image.

What one may first mistake as a mere framing device — not uncommon in adaptations that feel the need to explain their literary origins for the sake of the screen — the film constantly yanks us back to the Little Girl and the Aviator, and away from the Little Prince’s (Riley Osborne) narrative. In fact, given that Saint-Exupéry’s book is a collection of short fable-like stories strung together, it’s no surprise that Osborne (working off the screenplay by Irena Brignull and Bob Persichetti) quickly runs out of narrative for the eponymous and giggle-prone protagonist. It’s then one realizes that this adaptation is neither content in, nor intent on, merely bringing The Little Prince to screen, but rather that it seeks to model for us the very reading practice the story encourages, and thanks to which the book is one of the most beloved and iconic French properties in the world. In this sense, The Little Girl stands as the reader’s surrogate. Just as Saint-Exupéry’s narrator isn’t merely a passive presence in his own story (he’s compelled, after all, to author the story in the first place), and just as the Little Prince is a model for an active and engaged spectatorship (his incessant questions; his need for adventure), the Little Girl emerges as the contemporary extension of the book’s playful didacticism (when, for instance, in the book the Little Prince meets a vain man who only wishes to be flattered, we’re reminded that “conceited people never hear anything but praise,” the type of takeaway wisdom which recurs throughout the text).

The latter third of the film follows the Little Girl alongside her plush toy fox, as she journeys to find the Aviator’s lost friend. When she does find him the film becomes its own version of Hook, with a grown-up and not so Little Prince (the older version, “Mr. Prince”, voiced by Paul Rudd) needing to be reminded of what made him an avatar for the wonders of childhood in the first place. As with Hook’s revisionist take on J.M. Barrie’s work, we are reintroduced here to Saint-Exupéry’s cast of characters, who have grown beyond the clear and strict allegories of their names to be deployed in the real world as bleak adult types.

Just as children over the decades come to understand that the Businessman’s (Albert Brooks) avarice is absurd, and the Conceited Man’s (Ricky Gervais) vanity laughable, Osborne allows us to see how enshrined grownup values translate into a terrifying vision of an organized world, where the essential and purposeful are considered preeminent qualities — and where there’s little room given for children or their fancies. Admittedly didactic, this latter part of the film — which offers a third-act climax far more action-packed than the downturned ending of the book — functions as a narrative extension to the lessons Saint-Exupéry’s narrator threads throughout his wondrous memoir.

Osborne’s The Little Prince gives us a narrative of what it feels like to read that French story as well as what it looks like to embrace its life lessons: by the end, the Little Girl and her mother have settled into a much more relaxed rapport, one not determined or delimited by standardized tests or ideas of what it means to be an “essential” member of society. Just as Saint-Exupéry encourages his readers, here mother and daughter are seen looking up at the sky and its stars, asking themselves the question that still plagues the Aviator whenever he thinks of his young friend back on his home planet (“Is it yes or no? Has the sheep eaten the flower?”), and pondering the matters that are truly of the greatest importance.

‘The Little Prince’ is currently streaming on Netflix.