news

The National Book Awards Put Black Lives at the Center

In the middle of the broadcast, a heartfelt video celebrated Black writers, acknowledged their erasure, and pledged to do better

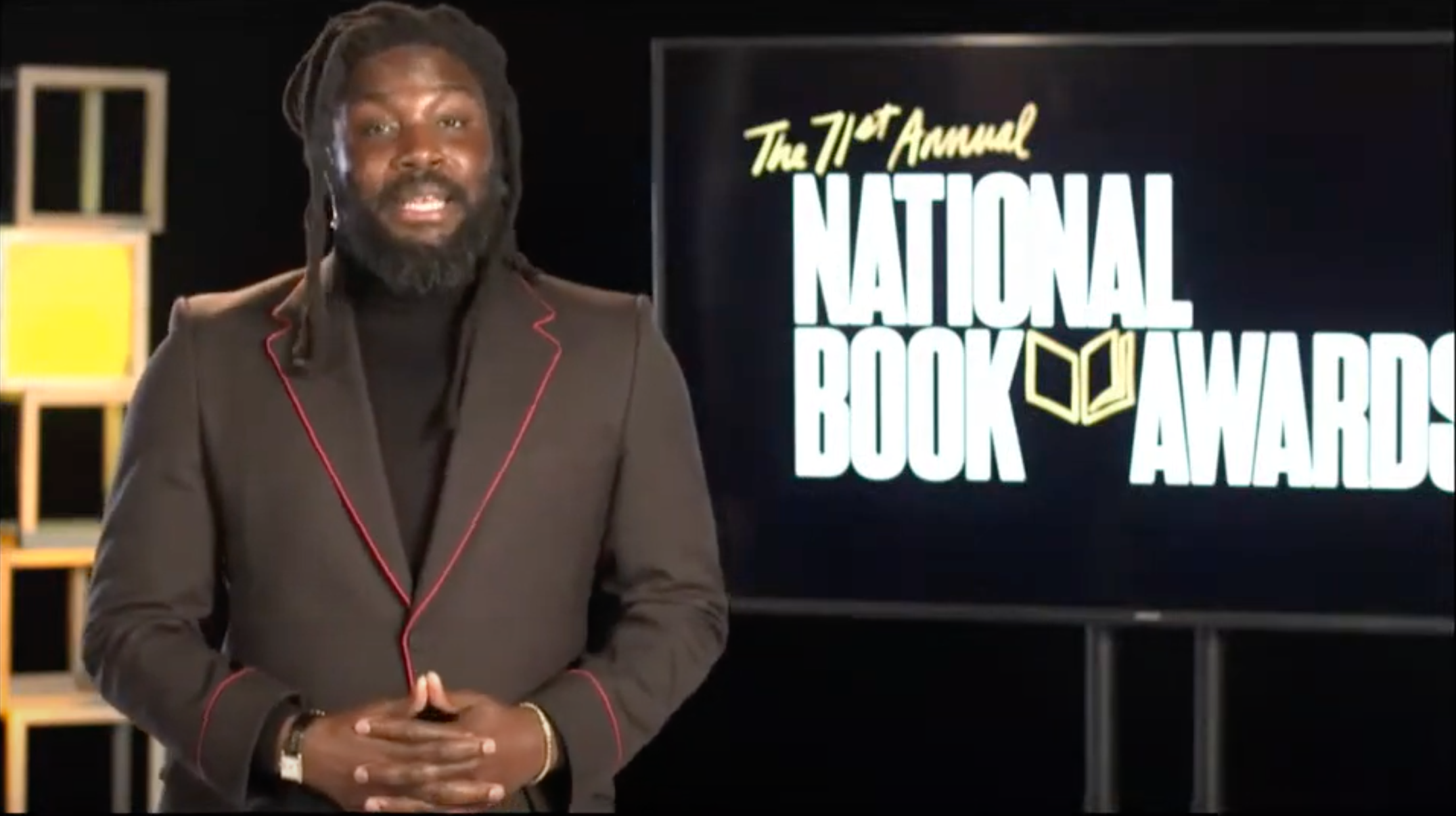

The fête that is the National Book Awards didn’t lose steam because we were separated in our homes due to quarantine. There remained intrigue, surprises, celebration, and tears. So many tears. Not only from stunned winners but from executive director Lisa Lucas, who tried to hold them back during a speech full of gratitude and memories. In two months’ time she’ll hold a new role as senior vice president at Pantheon Books and Schocken Books, but last night she and the entire National Book Foundation team along with host Jason Reynolds steered us through the annual commemoration of books, books, books. But this wasn’t only a salute to everything leading up to the evening. It was also a reflection on a mission touted even more loudly since Lucas’s arrival to the Foundation.

As is the usual format, the first honors of the evening tend to be the lifetime achievement awards. This year those accolades were bestowed to late Simon & Schuster CEO Carolyn Reidy (Literarian Award) and notable bestselling author Walter Mosley (Distinguished Contribution to American Letters). But in the middle, where there would normally be a break to dine, the screen instead faded to a video clip of 2011 poetry winner Nikky Finney’s speech where she talked about Black people being “explicitly forbidden to become literate” under slavery, and declared herself “officially speechless.” As her speech ended, a title card announced that the National Book Awards have been in existence since 1950 and “have honored over 2,700 books, becoming one of the most prestigious literary prizes in the world.” However, the text continued, only three writers of color were awarded prizes in the first 30 years of the Awards’ existence. They were Ralph Ellison (1953), Virginia Hamilton (1975), and Li Li Ch’en (1977)—I’ll also note that William Carlos Williams, of Puerto Rican–American descent, won the first award for poetry in 1950. Since 1999, a grand total of 13 writers of color have been awarded a National Book Award across categories. This data along with numerous stats over the years repeatedly conveys the limitations of the industry, not the artists.

Since 1999, a grand total of 13 writers of color have been awarded a National Book Award across categories.

At this point 2019 awards host LeVar Burton’s dulcet tones came in, conveying a firm commitment to “a National Book Awards that reflects the full depth and breadth of the human experience.” Over Burton’s declaration, viewers were greeted by an array of Black and Brown faces regarding their newly-won awards, and Black and Brown voices candidly discussing their challenges, beliefs, and love for the work they produced because we needed their stories as much as they needed to create them.

For her first win in 2011, Jesmyn Ward said Salvage the Bones was “a life’s work and I am only at the beginning.” How right she was—Ward would win her second award for fiction, becoming one of the few to do so, in 2017 for Sing Unburied Sing. Terrence Hayes, poetry winner in 2010, said “It’s such a futuristic idea. A world in which the descendants of slaves become poets”—a sentiment echoed a year later in Finney’s speech about forbidden literacy. Ta-Nehisi Coates, nonfiction winner in 2015 for Between the World and Me a testimony of the disregard for Black life in America, insisted “You will not enroll me in this lie” of “Black people having a predisposition to criminality.” And 2018 winner for young people’s literature Elizabeth Acevedo stated the importance of the work being not for this moment on stage but for those reached. “I am reminded of why this matters,” Acevedo said, “And that’s it not gonna be an award and it’s not gonna be an accolade. But it’s gonna be looking someone in the face and saying ‘I see you’ and in return being told that I am seen.”

Burton continued to infuse this moment with significance by consistently acknowledging an ongoing history that needs to demolished. This recognition alone does not initiate change, nor does it sustain it. It matters that what the National Book Awards did in this moment wasn’t a plea for donations; it was a call for the publishing industry to understand that the doors remain narrowly open, if open at all, for the rest of us and widely ajar for the chosen. How can we celebrate what has not been nurtured?

How can we celebrate what has not been nurtured?

In the last several years, the National Book Award longlist and finalist pool have been more ethnically representative—in 2018, as in 2020, BIPOC won in all five categories—and so have the judges. More representation in those reading has also lead to more representation in what gets recognized. What a concept.

It really doesn’t need to be said that representation is important. This truth is so evident to some (and to others appears to be a direct offense). But this year, from our homes, as many declarations have been made by many entities and individuals that they vehemently “believe Black Lives Matter,” it remains to be seen how much this statement aligns with a vision to make more space for Black lives to be in full view and without risk of being part of a “timely” interest. The work of artists then, artists now, and artists to come needs to be heralded and the creators need to know they’re not one of a few—they are part of an abundance.

As this segment concluded, Burton left us with these words: “When we say that Black Lives Matter, let us say it as acknowledgement of all those deserving writers, and by extension readers, who previously have been excluded from this room. Let us say it with an awareness of these voices, their value, and their ability to show us a way forward out of our current darkness. And let us say it in gratitude.” Let it also be said with resounding earnestness for the greatness on the horizon and the many honors they’ll achieve on stage and off.