Books & Culture

The Not-So-Hidden Racism of Nancy Drew

Can (white) America’s favorite girl detective overcome her past?

I named my first car, a mint green Toyota Prius, after my first role model, Nancy Drew. To me, it was the perfect homage: like Nancy, my car was pretty, capable, and ready for adventure.

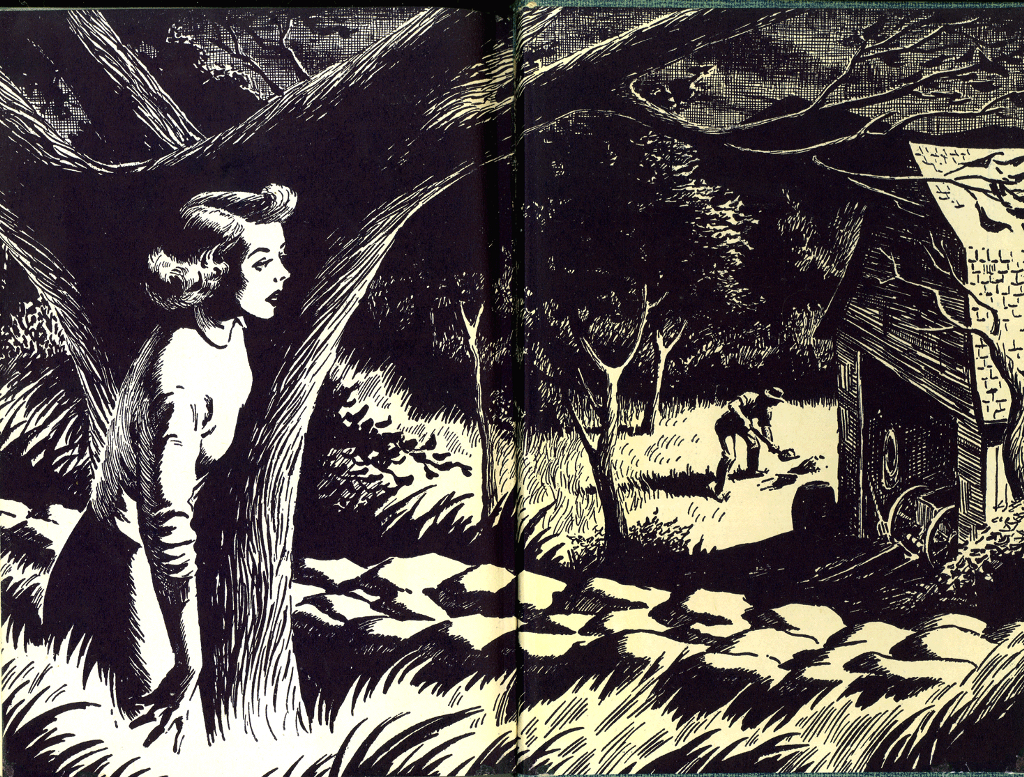

Women of many generations could claim a similar love of the girl detective. Before Buffy slayed her first vampire, before Wonder Woman lassoed the truth out of bad guys, before Leia led the Rebel Alliance, sixteen-year-old Nancy Drew sped her blue roadster all over River Heights catching criminals, getting dirty, and inspiring young girls to step outside of gender expectations.

When the first books were released in 1930, Nancy was an instant hit; to date, more than 80 million copies of her adventures have sold. However, the Nancy we know today is not the same Nancy readers first fell in love with. Thirty years after Nancy solved her first mystery, the original books were revised and shortened. Nancy aged to 18, drove a blue convertible, gained a surrogate mother in the form of her housekeeper, Hannah, and became, arguably, more docile. River Heights became less overtly racist but also more white. Since that first transformation the books have gone through a dozen iterations. These revisions offer one possible answer to the question of how to tackle outdated and harmful aspects of literature: try, try again. The recent controversy around the renaming of the American Library Association’s Laura Ingalls Wilder Award has propelled this question to the forefront of literary conversations in recent months. While the ALA has firmly stated the name change is about the award and is not a statement or recommendation regarding reading the classic Little House on the Prairie series, librarians, parents, and teachers have unsurprisingly found themselves asking: What do we do with these beloved books now?

The revisions to the original Nancy Drew books came in 1959 under the order of publisher Grosset & Dunlap for a variety of reasons — to modernize the series, to diminish publishing costs by shortening the books, and to rid the books of racist stereotypes.

Librarians, parents, and teachers have found themselves asking: What do we do with these beloved books now?

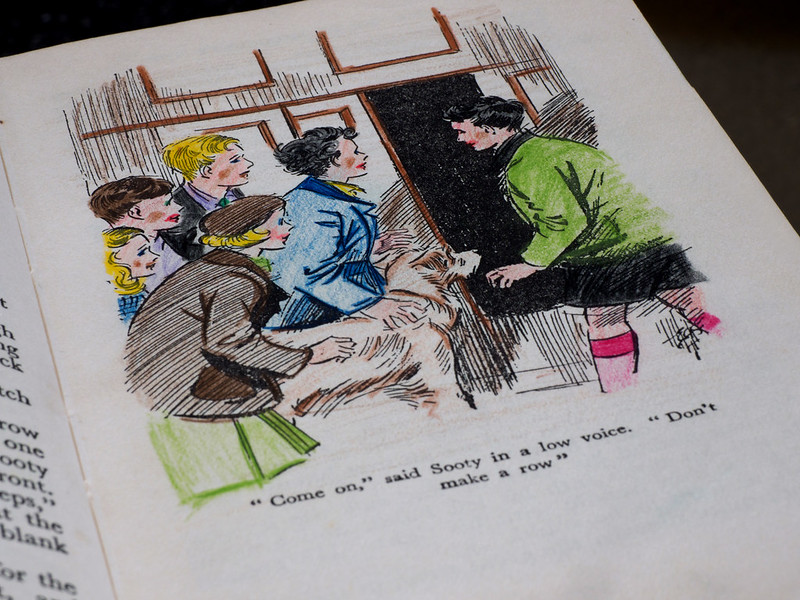

In the original 1930 version of The Secret of the Old Clock, the first book of the series, Nancy chases a clue to a lake bungalow. There, she interrupts a burglary in progress and is thrown into a closet and left to starve by one of the thieves. Eventually, she is freed by the bungalow’s caretaker, Jeff Tucker. Jeff Tucker is an African-American man who is portrayed as a child-like, speaking in dialect and easily fooled into intoxication by the robbers. Nancy scolds him for abandoning his post at the bungalow and grows frustrated when he slows her down by hosing himself off to sober up before they go to the police. At the station, Nancy marches to the front desk and demands to report a robbery, resulting in the marshal and several officers immediately emerging to hear her tale. Even when Jeff Tucker corroborates her story, they pile questions upon Nancy to clarify what he says. Tucker is “gently” pushed back from the car and left behind at the station while the rest, including Nancy, go after the thieves.

The contrast between Nancy and Jeff’s treatment at the police station is particularly disconcerting to me today. It brings to mind Emmett Till and the many instances of white women accusing Black men of various slights with deadly consequences. While Nancy only reports the robbery, her privilege as a wealthy white woman, demonstrated again and again in the book, is never as clear as this moment in the police station.

In the revised 1959 version of The Secret of the Old Clock, Jeff Tucker is white, and he hasn’t been tricked into drinking by the thieves, but is instead locked up in a shed. Nancy comforts him when he frets over losing his job rather than scolding him. At the police station, Jeff Tucker shares his version of the story with no trouble and is advised to call his son for a ride back home. This revision is emblematic of how Grosset & Dunlap chose to deal with the racism in the original texts — simple erasure. River Heights became mono-color.

This revision is emblematic of how Grosset & Dunlap chose to deal with the racism in the original texts — simple erasure. River Heights became mono-color.

While there are many who would say good riddance and allow the original Nancy Drew books to fade into obscurity, Phil Zuckerman, founder of Applewood Books saw value in them despite problematic scenes. In 1991, Applewood Books reissued the first three books in their original forms as an attempt to cash in on the nostalgia of baby boomers who knew and loved the first Nancy best. Zuckerman believed that the quality of writing of the original books outweighed the racism.

The publisher’s note at the beginning of each reprint acknowledges the “racial and social stereotyping” in the books as something the modern reader may be “extremely uncomfortable with” and that the stereotypes may provoke a “response in the modern reader that was not felt by the reader of the times.” Both phrases invoke a white modern reader as well as a white reader of the times. What they fail to consider is what the modern reader of color might feel — and what readers of color felt back then. It is likely a feeling significantly more damaging and painful than extreme discomfort. As a Korean American child, the stereotypes I encountered about Asians in popular media not only provoked anger, sadness, and pain, but were also internalized by me and other consumers — Asian or not. By ignoring the deliberate harm stereotypes were created to inflict, the publisher’s note fails to provide crucial context as well as fully acknowledge the damage of scenes like the one with Jeff Tucker for readers at the time and today.

The reprints went on to sell well enough that Applewood re-released seven additional Nancy Drew originals. I remember reading the reprinted original of The Secret of the Old Clock as a teenager, after having grown up with the revised versions. I recall enjoying the other historical aspects of the book: Nancy’s old roadster, the formalities in conversation, how Nancy ordered dresses to be tailored and shipped home. I remember thinking the Jeff Tucker scene was certainly racist, but did not interrogate it further. Without a full understanding of the history of the stereotyping, I knew it was bad and left it at that. Like Applewood banked on, I was caught up in the nostalgia of Nancy’s adventures. At that age, it hadn’t yet occurred to me that while Nancy was at the center of the novel, her story wasn’t the only one to pay attention to. In a classroom with a great teacher, or with a discussion guide of pointed questions, perhaps I could have gotten more out of it. Perhaps with more acknowledgement, an African American teen would have felt visible in their reaction to that scene. Perhaps guided reading is an answer to the big question posed above. But that may not be enough to warrant keeping these books on the shelves.

The publisher’s note on reprints invokes a white modern reader as well as a white reader of the times. What it fails to consider is what the modern reader of color might feel — and what readers of color felt back then.

Just like in the case of Wilder’s Little House series, there are no easy answers on how to approach its long history and racist past. To leave those texts in the past may feel right for some, and like erasure for others. The ugliness of America’s racism is something that cannot be swept under the rug, yet without the proper context and guidance, particularly for children, the revival of these stories continues a cycle of pain and re-traumatization. What’s certain is that more perspectives besides the default white one need to be considered when leading readers to these texts and determining which to celebrate as “Classics.”

Nancy has lived on with wavering success. New off-shoot series have included The Nancy Drew Files and Girl Detective, both met with criticism for portraying a Nancy with more romantic subplots and less of her earlier brilliance. By disposing of what appealed readers to Nancy in the first place — her grit, intelligence, and bravery — publishers homed in on what they thought teen girls cared about: boys and shopping. A scantily clad Nancy on covers, who spends time thinking about the men in her life instead of mysteries seems to reflect a straight male’s idea of an appealing young woman rather than the perspective of the intended audience. The 2007 movie starring Emma Roberts was met with lukewarm reviews, ultimately failing to breathe new life into the character as well.

Perhaps one of the biggest shake-ups to the series occurred last month with the release of the New Nancy Drew Mystery Stories, an intersectional graphic novel adaptation. In this iteration of River Heights, which takes place in the present, Nancy’s two best friends and sometimes co-detectives, Bess and George, are a woman of color and queer teen, respectively. Moreover, George’s girlfriend is Black. While some backlash is to be expected for any rebooted series, Nancy is, once again, meeting the expectations of the times. Demand for representation is at an all-time high in media, and publishers whether nobly for monetary reasons or other are taking note.

Even with this movement in the right direction, away from the stereotypical Jeff Tuckers and towards a colorful, LGBTQ-friendly River Heights, the question I’m left with is when — if ever — will we see a Black Nancy? An Asian Nancy? A queer Nancy? When color only appears at the edges, marginalized groups remain marginalized. Imagine that scene of Nancy at the police station demanding to report a robbery. Now imagine she is Black. Even today, a Nancy Drew of color would not wield the same privilege a white Nancy has. Changing our titular character in this way would be an opportunity to explore the complexities of the feminism of Nancy Drew, and put a young, capable woman of color front and center, drawing an even larger audience in to this well-loved, long-lasting series.

In 2016, we saw a glimmer of this possibility. CBS developed a pilot of a Nancy Drew TV show, with an older Nancy serving as an NYPD police officer. While the premise left much to be desired in comparison to the books, the casting of Iranian and Spanish actress Sarah Shahi was exciting. Unfortunately, the pilot was not picked up and, while the show is being shopped around to other networks, even if it is picked up the entire cast will be replaced.

For nearly 90 years, Nancy Drew has managed to stay relevant through reinvention and reboots, thanks to her adaptability as a character. Ultimately, Nancy Drew is all things — Midwestern and polite while also cultured and quick-witted; feminine and pretty, yet athletic and tough; popular and wealthy while simultaneously humble and generous. Her near perfection makes her inhuman which in turn makes her easily adaptable to the standards of perfection as they shift over time. The truth is, it’s not Nancy readers fall in love with, but the idea of her and the ideals she represents — bravery, justice, independence. In the real world, her name carries the same credibility it does within the fictional world of River Heights. For this reason, this world needs a Nancy Drew who steps out of the white, middle-upper class mold, who can not only counterbalance the racism that led to the original Jeff Tucker, but grapple with it. She can examine with her magnifying glass the ideals of diversity. Inclusivity. Equity. That’s the Nancy Drew all girls deserve.