Lit Mags

The Patron Saint of Healers, Whores & Righteous Thieves

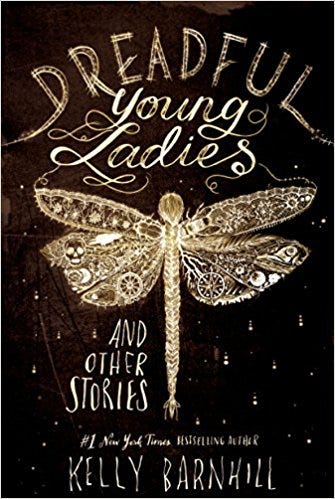

“Elegy to Gabrielle” by Kelly Barnhill, recommended by Pete Hautman

AN INTRODUCTION BY PETE HAUTMAN

Some stories are best encountered at unexpected times in unexpected places. Yellowed pages found tacked to tree trunks in a forest, or served between the antipasti and the primo beneath a sterling silver dome, or discovered on a remote Caribbean islet, in a cave, sealed in a teak chest, keeping company with a skeleton.

Such stories demand the attention of the reader, while asking them to bring nothing. Therefore, I will tell you nothing about “Elegy to Gabrielle.” To see it coming might diminish it; to have expectations would be to misinterpret it. Instead, I will tell you something of the author.

Kelly Barnhill is a weirdo. I know this because she told me so, and because her stories of dreadful, terrible, passionate, immoderate, young women are undeniably the product of a weird imagination. I know many, many writers, and weirdness is endemic to the species. Whether the weirdness is a product of the writing, or vice versa, I don’t know. In any case, it’s not a glitch; it’s a feature.

That weirdness manifests as a sort of hyper-developed peripheral vision: it enables a writer to see things that might not withstand direct scrutiny and bring them into startling focus — a literary circumvention of the physicists’ observer effect.

Kelly Barnhill possesses this gift in abundance. She shows us things that are not real, but are nevertheless true; things that we know to be important even though they may not exist. To put it another way, she writes fairy tales. Fairy tales written in lush, insistent, dreamlike prose. Yarns that the Grimm brothers never dreamed. Some of her stories are written to be read by children, but all of her stories are for adults. Kelly Barnhill is astonishingly good at this. I don’t know how she does it.

Now I fear I have said too much. My recommendation? Breathe out. Expect nothing. Close your eyes and jump. Breathe in.

Pete Hautman

Author of Slider

The Patron Saint of Healers, Whores & Righteous Thieves

Kelly Barnhill

Share article

“Elegy to Gabrielle”

by Kelly Barnhill

Curator’s note: The following pages were found in a cave on an islet eleven miles southwest of Barbados. The narrative is, of course, incomplete, disjointed, and unreliable, as is the information contained within its pages. There is no record of Brother Marcel Renau living in the Monastery of the Holy Veil during the years in question. There is a record of the order for the execution of a Gabrielle Belain in St. Pierre in 1698; however, no documentation of the actual execution exists. Some of this narrative is indecipherable. Some is lost forever. Most, if not all, is blatantly untrue, the ravings of a lost sailor gone mad without water. As to the conditions in which these writings were found: this too remains a puzzle. The cave was dry and protected and utterly empty except for three things: a human skeleton, curled in the corner as though sleeping; a two-foot length of human hair, braided tightly with a length of ribbon and a length of rope, laid across the hands of the dead man; and an oiled and locked box made of teak, in which these documents were found. Across the lid of the box the following words had been roughly scratched into the wood, as though with a crude knife or a sharp rock: “Bonsoir, Papa.”

Two days before Gabrielle Belain (the pirate, the witch, the revolutionary) was to be executed, a red bird flew low over the fish market, startling four mules, ten chickens, countless matrons, and the Lord High Constable. It flew in a wide spiral higher and higher until it reached the window of the tower where my beloved Gabrielle awaited her fate. People say that she came to the window, that the shadows from the bars cut across her lovely face. People say that she reached out a delicate, slightly freckled hand to the bird’s mouth. People say that she began to sing.

I stood in the hallway with the two guards, negotiating the transfer of food, water, and absolution across the threshold of the wood and iron door that blocked Gabrielle from the world. I did not see the bird. I did not hear song. But I believe them both to be real. This is the nature of existence: We believe, and it is. Perhaps God will turn His back on me for writing such heresy, but I swear it’s the truth. Gabrielle, like her mother before her, was a Saint Among Men, a living manifestation of the power of God. People believed it, therefore it was true, and no demonstration of the cynical power of bureaucrats and governments and states could unbelieve their believing.

Gabrielle Belain, at the age of ten, walked from the cottage where she lived with her mother past the Pleasure House to the shore. The moon, a thin slash on a glittering sky, cast a pale light on the foamy sand. She peered out onto the water. The ship, hidden in darkness, was still there, its black sails furled and lashed to the tethered boom, its tarred hull creaking in the waves. She could feel it. Actually, there was never a time when she could not feel it. Even when it was as far away as Portugal or Easter Island or the far tip of the continent, she knew where the ship was. And she knew she belonged to it.

Four porpoises bobbed in the waves, waiting for the child to wade in. They made no sound, but watched, their black eyes flashing over the bubbling surf. A mongrel dog, nearly as tall as the girl, whined piteously and rubbed its nose to her shoulder.

“You can’t come,” she said.

The dog growled in response.

Gabrielle shrugged. “Fine,” she said. “Please yourself. I won’t wait for you.” She waded in, caught hold of a porpoise fin, and swam out into the darkness, the dog paddling and sputtering behind her.

The sailors on the quiet ship watched the sky, listened to the wind. They waited. They had been waiting for ten years.

By the time Gabrielle was thirteen, she was the ship’s navigator. By the time she was fifteen, she was captain, and a scourge to princes and merchants and slave traders. By the time she was eighteen, she was in prison — chained, starved, and measured and weighed for hanging.

At night, I see their hands. I do not see their faces. I pray, with my rattling breath, with the slow ooze of my blistered skin, with my vanishing, worthless life, that I may see their faces again before I die. For now, I must content myself with hands. The hands of Gabrielle, who thwarted governors, generals, and even the king himself, and the hands of her mother, who healed, who prayed, and God help me, who loved me. Once. But oh! Once!

Gabrielle’s mother, Marguerite Belain, came from France to Martinique in the cover and care of my order as we sailed across the ocean to establish a new fortress of prayer and learning in the lush, fragrant islands of the New World. It was not our intention to harbor a fugitive, let alone a female fugitive. We learned of Marguerite’s detention through our contacts with the Sisters of the Seventh Sorrow, several of whom waited upon the new and most beloved lover of the young and guileless king. Although the mistress had managed to bear children in her previous marriage, with the king she was weak-wombed, and her babes flowed, purple and shrunken, into her monthly rags with much weeping and sorrow in the royal chambers. Marguerite was summoned to the bed of the mistress, her womb now quickening once again.

“Please,” the mistress begged, tears flowing down those alabaster cheeks. “Please,” she said, her marble mouth, carved always in an expression of supercilious disdain, now trembling, cracking, breaking to bits.

Marguerite laid her hands on the belly of the king’s beloved. She saw the child, its limbs curled tightly in its liquid world. The womb, she knew, would not hold. She saw, however, that it could, that the path to wholeness was clear, and that the child could be born, saved, if certain steps were taken immediately.

But that was not all she saw.

She also saw the child, its grasping hands, its cold, cold eye. She saw the child as it grew in the seat of authority and money and military might. She saw the youth who would set his teeth upon the quivering world and tear upon its beating heart. She saw a man who would bring men to their knees, who would stand upon the throats of women, whose hunger for power would never cease.

“I cannot save this child,” Marguerite said, her leaf green eyes averted to the ground.

“You can,” the mistress said, her granite lips remaking themselves. “And you will.”

But Marguerite would not, and she was duly imprisoned for the duration of the pregnancy, until upon the birth she would be guillotined as a murderess if the child did not live and as a charlatan if it did.

It did not. But it did not matter: Marguerite had been spirited away, disguised in our habit and smuggled onto our ship of seafaring brethren before the palace ever did turn black with mourning.

I helped her escape, my Brothers and I. I placed our rough robes over those blessed shoulders, and helped her to wind her hair into the darkness of the cowl. I pulled it low over her face, hiding her from the world, and took her hand as we hurried through the city’s underground corridors, never stopping until we made it to the harbor, and hid her in an empty wine barrel on our ship. I told myself that the thudding of my heart was due to the urgency of our action. I told myself that the hand that I held in my hand was beloved because we are all beloved by God. To be human is to lie, after all. Our minds tell lies to our hearts and our hearts tell lies to our souls.

It was on the eighteenth day of our voyage that Marguerite gave me leave into her chamber. It was unasked for and yet longed for all the same, and came to me the way any miracle occurs — in a moment of astonishment and deep joy. On that same day — indeed, that same moment — a storm swirled from nowhere, sending the wind and sea to hurl themselves against the groaning hull, and striking the starboard deck with lightning.

Was it the feeble lover, I wondered, or the lightning that produced such a child when she bore a babe with glittering eyes?

Gabrielle. My child. I am supposed to say the issue of my sin, but I cannot. How can sin produce a child such as this?

On the morning of the forty-first day, a ship with black sails appeared in the distance. By noon we could see the glint of curved swords, the ragged snarl of ravenous teeth. By midafternoon, the ship had lashed itself to ours and the men climbed aboard. In anticipation of their arrival, we set food and drink on the deck and opened several — although not all — of our moneyboxes, allowing our gold to shine in the sun. We huddled together before the mainmast, our fingers following prayer after prayer on our well-worn rosaries. I reached for Marguerite, but she was gone.

A man limped from their ship to ours. A man whose face curled in upon itself, whose lashless eyes peered coldly from a sagging brow, whose mouth set itself in a grim, ragged gash in a pitiless jaw. A mouth like an unhealed wound.

Marguerite approached and stood before him. “You are he,” she said.

He stared at her, his cold eyes widening softly with curiosity. “I am,” he said. He was proud, of course. Who else would he be? Or, more importantly, who else would he desire to be? He reached for the cowl that hid the top of her head and shadowed her face and pulled it off. Her hair, the color of wheat, spilled out, poured over the rough cloth that hid her body from the world, pooled over her hands, and around her feet. “And you, apparently, are she.”

She did not answer, but laid her hands upon his cheeks instead. She looked intently into his face, and he returned her gaze, his hard eyes light with tears. “You’re sick,” she said. “You have been for . . . ever so long. And sad as well. I cannot heal the sadness, but I can heal the sickness. He too suffers.” She pointed to the pockmarked man holding a knife to the throat of our beloved Abbot. “And he, and he.” She pointed to other men on the ship. Walking over to the youngest man, who leaned greenly against the starboard gunnels, she laid her hand on his shoulder. “You, my love, I cannot save. I am so sorry.” Tears slipped down her cream and nutmeg skin. The man — barely a man, a boy, in truth — bowed his head sadly. “But I can make it so it will not hurt.” She took his hand, and squeezed it in her own. She brought her pale lips to his smooth brown cheek and kissed him. He nodded and smiled.

Marguerite ordered a bucket to be lowered and filled with seawater. She laid the bucket at the feet of the captain. Dipping her hands in the water, she anointed his head, then his hands and his feet. She laid her ear upon his neck, then his heart, then his belly. Then, scooping seawater into her left hand, she asked the pirate captain to spit into its center. He did, and immediately the water became light, and the light became feathers, and the feathers became a red bird with a green beak who howled its name to the sky. It flew straight up, circled the mainmast, and spiraled down, settling on the captain’s right shoulder.

“Don’t lose him,” she said to the captain.

In this way she healed those who were sick, and soothed the one who was dying, giving each his own familiar: a one-eared cat, an air-breathing fish, a blue albatross, and a silver snake.

When she finished, she turned to the captain. “Now you will return to your ship and we will continue our journey.”

The captain nodded and smiled. “Of course, madam. But the child in your womb will return to us. She was conceived on the sea and will return to the sea. When she is old enough we will not come for her. We will not need to. She will find us.”

Marguerite blinked, bit her lip so hard she drew blood, and returned to the hold without a word. She did not emerge until we made land.

Our brethren that had preceded us met us on the quay and led us to the temporary shelters that crouched, like lichen, on the rock. That the new church with its accompanying cloister and school were unfinished, we knew. But the extent of the disorder was an unconcealed shock to all of us, especially our poor Brother Abbot, whose face was stricken at the sight of the mossy stones upon the ground.

Brother Builder hung his head for the shame of it. “This is a place of entropy and decay,” he muttered to me when the Abbot had gone. “Split wood will not dry, but erupts with mushrooms, though it has heated and cured for days. Cleared land, burned to the ground, will sprout within the hour with plants that we cannot identify or name — but all our seeds have rotted. Keystones crack from the weight of ivy and sweet, heavy blossoms that were not there the night before. The land, it seems, does not wish us to build.”

The Abbot contacted the Governor, who conscripted paid laborers at our insistence — freemen and indentured, Taino and grim-faced Huguenots — to assist with the building, and soon we had not only church and cloister, but library, bindery, stables, root cellars, barrel houses, and distilleries.

Desperately, I hoped that Marguerite would be allowed to stay. I hoped that the Abbot would build her a cottage by the sea where she could keep a garden and sew for the abbey. Of course, she could not. The Abbot gave her a temporary shelter to herself, forcing many of the brethren to squeeze together on narrow cots, but no one grumbled. At the end of our first month on the island, she left without saying good-bye. I saw her on the road as the sun was rising, her satchel slung across her back. Her hair was uncovered and fell in a loose plait down her back, curling at the tops of her boots. I saw her and called her name. She turned and waved but said nothing. She did not need to. The sunlight bearing down on her small frame illuminated at last that to which I had been blind. Her belly had begun to swell.

Gabrielle was born in the vegetable garden that separated the Pleasure House from the small cottage where Marguerite lived and worked. Though the prostitutes gave her shelter in exchange for her skills as a cook, a gardener, and a healer, it soon became clear that her gifts were greater and more numerous than originally thought. As Marguerite’s pregnancy progressed, the gardens surrounding the Pleasure House thrived beyond all imaginings.

Guavas grew to the size of infants, berries spilled across the lawns, staining the stone walkways and steps a rich, dark red, like blood coursing into a beating heart. Vines, thick and strong as saplings, snaked upward along the whitewashed plaster, erupting in multi-colored petals that fluttered from the roof like flags.

Marguerite, when the time came, knelt among the casaba melons and lifted her small hands to the bright sky. Immediately, a cloud of butterflies alighted on her fingers, her heaving shoulders, her rivers of gold hair, as the babe kicked, pressed, and slipped into the bundle of leaves that cradled her to the welcoming earth.

The girls of the Pleasure House saw this. They told the story to everyone. Everyone believed it.

After Gabrielle was born, Marguerite scooped up the afterbirth and buried it at the foot of the guava tree. The girls of the Pleasure House gathered about her to wash the baby, to wheedle the new mother to bed, but Marguerite would not have it. She brought the baby to the spot where the placenta was buried.

“You see this?” she said to the baby. “You are rooted. Here. And here you will stay. The captain can believe what he will, but you are not a thing of water. You are a child of earth. And of me. And I am here.” And with that she went inside and nursed her baby.

Though I assume it was well known that the babe with glittering eyes was the product of the one time (but oh! Once!) that Marguerite Belain consented to love me, we had chosen to believe that the child was a miracle, conceived of lightning, of sea, of the healing goodness of her mother. And in that believing, it became true. Gabrielle was not mine.

For months, the Abbot sent a convoy of monks to the little cottage behind the Pleasure House to argue in favor of a baptism for the child. Marguerite would not consent. No water, save from the spring that bubbled a mile inland, would touch Gabrielle. She would not bathe in the sea. She would not taste or touch water that came from any but her mother’s hand.

“She will be rooted,” she said. “And she will never float away.” After a time, the girls of the Pleasure House emerged to shoo us off. They had all of them grown in health and beauty since Marguerite’s arrival. Their faces freshened, their hair grew bright and strong, and any whiff of the pox or madness or both had dissipated and disappeared. Moreover, their guests, arriving in the throes of hunger and lust, went away sated, soothed, and alive. They became better men. They were gentler with their wives, loving with their children. They fixed the roof of the church, rebuilt the washed-out roads, took in their neighbors after disasters. They lived long, healthy, happy lives and died rich.

Gabrielle Belain was never baptized, though in my dreams, I held that glittering child in my arms and waded into the sea to my waist. In my dream, I scooped up the sea in my right hand and let it run over the red curls of the child that was mine and not mine. Mostly not mine. In my dream, a red bird circled down from the sky, hovered for a moment before us, and kissed her rose-bud mouth.

When Gabrielle was six years old, she wandered out of the garden and down the road to the town square. Her red curls shone with ribbon and oil, and her frock was blue and pretty and new. The girls of the Pleasure House, none of whom bore children of their own, doted on the child, spoiling her with dresses and hats and dolls and sweets. To be fair, though, the girl did not spoil, but only grew in sweetness and spark.

On the road, Gabrielle saw a mongrel dog that had been lamed in a fight. It was enormous, almost the size of a pony, with grizzled fur hanging about its wide, snarling mouth. It panted under the star apple tree, whining and showing its teeth. Gabrielle approached the animal, looked up at the branches heavy with fruit, and held out her hand. A star apple, dark and smooth, fell neatly into her little hand, its skin already bursting with sweet juice. She knelt before the dog.

“Eat,” she said. The dog ate. Immediately, it stood, healed, nuzzled its new mistress, shaking its tail earnestly, and allowed her to climb upon its back. In the market square, people stopped and stared at the pretty little girl riding the mongrel dog. They offered her sweets and fruits and bits of fabric that might please a little child. She came to the fishmonger’s stall. The fishmonger, an old, sour man, was in the middle of negotiating a price with an older, sourer man, and did not notice Gabrielle. A large marlin, quite dead, leaned over the side of the cart, its angled mouth slightly open as though attempting to breathe. Gabrielle, a tender child, put her hand to her mouth and blew the fish a kiss. The fishmonger, satisfied that he had successfully bilked his customer out of more gold than he had made all the week before, looked down and was amazed to see his fish flapping and twisting in the rough-hewn cart. The marlin leapt into the air and gave the customer a sure smack against his wrinkled cheek, before hurling itself onto the cobbled path and wriggling its way to the dock. Similarly, the other fish began to wiggle and jump, tumbling and churning against each other in a jumbled mass toward freedom. People gawked and pointed and gathered as the fishmonger vainly tried to gather the fish in his arms, but he had no idea what to do without the aid of his nets, and his nets were being mended by his foulmouthed wife in their little hovel by the sea.

Gabrielle and her dog, realizing that there was nothing more to see, moved closer to the fine house and tower that served as the Governor’s residence and court and prison. To the side of the deeply polished doors, carved with curving branches and flowers and images of France, was the raised dais where men and women and children in chains stood silently, waiting to be priced, purchased, and hauled away. The man in the powdered wig who called out the fine qualities of the man in chains on his left did not notice the little girl riding the dog. But the man in chains did. She looked up at him, her freckled nose wrinkled in concentration, her green eyes squinting in the sun. She smiled at the man in chains and waved at him. He did not smile back — how could he? — but his eye caught the child’s gaze and held it. Gabrielle watched his hands open and close, open and close, as though grasping and regrasping something invisible, endurable, and true. Something that could not be taken away.

The child began to sing — softly at first. And at first no one noticed. I stood in the receiving room of the Governor’s mansion, waiting to receive dictation for letters going to the governors of other Caribbean territories, to the Mayor and High Inquisitor of New Orleans, and to the advisors to the king himself. This was our tribute to the Governor: rum, wine, transcribed books, and my hands. And for these gifts he left us mostly alone to live and work as pleased God.

Through the window I saw the child who came to me nightly in dreams. I heard the song. I sang too.

The people in the square, distracted by the escaping fish, did not notice the growing cloud of birds that blew in from the sea on one side and the forest on the other. They did not notice how the birds circled over the place where the people stood, waiting to be sold. They did not notice the bright cacophony of feathers, beaks, and talons descending on the dais.

Two big albatrosses upset the traders’ moneyboxes, sending gold spilling onto the dirt. A thousand finches flew in the faces of the guards and officers keeping watch over the square. A dozen parrots landed on the ground next to Gabrielle and sang along with her, though badly and off-key. And hundreds of other birds — and not just birds of the island, birds from everywhere, birds of every type, species, description, and name — spiraled around every man, woman, and child, obscuring vision and confounding hand, foot, and reckoning, before alighting suddenly skyward and vanishing in the low clouds. Gabrielle, her song ended, rode slowly away, as though nothing out of the ordinary had happened. It was several moments before anyone realized that the dais was now empty, and each soul waiting for sale had vanished, utterly. All that was left was an assortment of empty chains lying on the ground.

For weeks after, the Governor, who had invested heavily in the slave-bearing ship and had lost a considerable sum in the disappearing cargo, sent interrogators, spies, and thieves into every home in the town, and while no one knew what had happened or why, everyone commented on the strange, beautiful little girl riding a mongrel dog.

From his balcony atop the mansion, the Governor could see the road that led away from the town, through the groves of fruit trees, through forest, to the Pleasure House and the little cottage surrounded by outrageously fertile gardens. He could see the golden-haired woman with her redheaded child. His breath was a cold wind, his face a merciless wave. A storm gathered in the town, preparing to crush my little Gabrielle.

I went with the Abbot to the cottage behind the Pleasure House, prepared to plead our case. It was not the first time. As the grumblings from the mansion grew louder and more insistent, we wrote letters in secret, sending them to the other islands and to France. Marguerite, dressed in a plain white linen shift, her golden hair braided and looped around her waist like a belt, laid out plates laden with fruit and bread and fish. Gabrielle sat in the corner on a little sleeping pallet. She was nine now and able to read. She came to the abbey often to look at Bibles and maps and poetry. What she read, she memorized. Once she was heard reciting the entire book of Psalms while perched high in a tree gathering nuts.

“Eat,” Marguerite said to us, sitting opposite on the wooden bench and taking out her sewing.

“Later,” the Abbot said, waving the plate away impatiently with his left hand. “Your child is not safe here anymore. You know this, my daughter. The Governor has his spies and assassins everywhere. We could hide her in the abbey, but for how long? It is only at my intercession that he has not come this far down the road, but neither of you is safe within a mile of the town.”

“We need nothing from town,” Marguerite said, filling our glasses with wine. “Drink,” she commanded.

I brought my fist to the table. Gabrielle sat up with a start. “No,” I said. “She cannot stay. I will accompany her back to France, and the Sisters of the Seventh Sorrow will protect her and educate her. No one will know whose child she is. No one will know of the Governor’s hatred. She will be safe.”

Marguerite took my fist and eased it open, laying her palm upon my palm. She looked at the Abbot and then at me.

“She is rooted here. I rooted her myself. She will not go to the sea. There is nothing more to say. Now. Eat.”

We ate. And drank. The wine tasted of flowers, of love, of mother’s milk, of sweat and flesh and dreaming. The food tasted like thought, like memory, like the pale whisperings of God. I dreamed of Gabrielle, growing, walking upon the water, standing with a sword against the sun. I dreamed of the taste of Marguerite’s mouth.

The Abbot and I woke under a tree next to the abbey’s stable.

There was no need to say anything, so we went in for matins.

The next day, a ship with black sails appeared a mile out to sea. The girls of the Pleasure House reported that Marguerite went to the shore, screaming at the ship to depart. It did not. She called to the wind, to the ocean, to the birds, but no one assisted. The ship stayed where it was.

Soldiers came for Gabrielle. Marguerite saw them come. She stood on the roof of her house and raised her hands to the growing clouds. The soldiers looked up and saw that the sky rained flower petals. The petals came down in thick torrents, blinding all who were outdoors. With the petals came seeds and saplings, rooting themselves firmly in the overripe earth. The soldiers scattered, wandering blindly into the forest. Most never returned.

The next day, a thicket of trees grew up around the Pleasure House and the little cottage behind, along with a labyrinthine network of footpaths and trails. Few knew the way in or out. Whether the girls of the Pleasure House grumbled about this, no one knew. They appeared to have no trouble negotiating their way through the thicket, and trained a young boy, the son of the oyster diver, to stand at the entrance and guide men. If an agent of the Governor approached, the boy darted into the trees and disappeared. He was never followed.

The morning of Gabrielle’s tenth birthday, a storm raged from the west, then from the north, then from the east. Everyone on the island prepared for the worst. Anything that could be lashed was lashed. We boarded ourselves in, or ran for high ground. Outside, the wind howled and thrashed against our houses and buildings. The sea churned and swelled before rearing up and crashing down upon the island. Most of the buildings remained more or less intact. At the abbey, the chapel flooded, as did the library, though most of the collection was saved. Several animals died when the smaller stable collapsed.

Once the rains subsided, I journeyed through the thick and cloying mud to check on Marguerite. I found her kneeling in the vegetable patch, weeping as though her heart would break. I knelt down next to her, though I don’t think she noticed me at first. Her pale hands covered her face, and tears ran down her long fingers like pearls. She turned, looked at me full in the face with an expression of such sadness that I found myself weeping though I did not know why.

“The guava tree,” she said. “The sea took it away.”

It was true. Instead of the broad smooth trunk and the reaching branches, a hole gaped before us like a wound. Even the roots were gone.

“There is nothing to hold her here,” she said. And for the first time since the night in the ship’s hold during the storm all those years ago, I reached my arm across her back and coaxed her head to my shoulder. Her hair smelled of cloves and loam and salt. Gabrielle stood on the rocks at the shore, gathering seaweed into a basket to be used for soup. Her dog stayed close to her heels, as though Gabrielle might, at any moment, go skipping away. From time to time, the child peered out at the water, her eyes fixed on the rim of the ocean, or perhaps on something hovering just past the horizon — something that Marguerite and I could not see.

Two weeks later, Gabrielle Belain was gone. She slipped out to sea on the back of a porpoise, and she did not return to the island, except at last in chains in the belly of a prison ship.

From the window in the library, I saw the ship with black sails unfurl itself, draw its anchors, and sail away. From the forest surrounding the Pleasure House, a sound erupted, echoing across the shore, down the road, and deep into the wild lands of the island’s interior. A deep, mournful, sorrowing cry. A dark cloud emerged over the forest and grew quickly across the island, heavy with rain and lightning. It rained for eighteen days. The road washed away, as did the foundations of houses, as well as gardens and huts that had not been securely fastened to the ground.

The Abbot went alone to the place where Marguerite wept. He brought no one with him, but when he returned, the sun reappeared, and Marguerite returned to her work healing sickness and coaxing abundance from the ground.

Every day, she made boats out of leaf and flower and moss, and every day she set them in the waves and watched them disappear across the sea.

Some years later, shortly after Gabrielle reached her fifteenth year, the captain called Gabrielle to his quarters when the pain in his chest grew intolerable.

“The weight of the world, my girl, rests upon my chest, and even your mother wouldn’t be able to fix it this time. That’s saying something, isn’t it?” He laughed, which became a cough, which became a cry of pain.

Gabrielle said nothing, but took his hand between her own and held it as though praying. There was no use arguing. She could see the life paths in other people, and was able to find detours and shortcuts when available to avoid illness or pain or even death. There was no alternate route for her beloved captain. His path would end here.

The red bird whined in its cage, flapping its wings piteously. “I thought that bird would die with me, but he looks like he’s in the prime of his life. Don’t lose him, girl.” He did not explain, and she did not ask.

The captain died, naming Gabrielle his successor, which the crew accepted as both wise and inevitable. As captain, Gabrielle Belain emptied many of the ships heading toward the holdings of the Governor, as well as redirected ships with human cargo, placing maps, compasses, swords, and ship wheels in the palms of hands that once bore chains, and setting the would-be slavers adrift with only a day’s worth of food and water and a book of prayers to help them to repent. The freed ships followed flocks of birds toward home, and Gabrielle prayed that they made it safely. The Governor lost thousands, and thousands more, until he was at the brink of ruination, though he attempted to hide it. This caused the pirates no end of delight.

The red bird remained in his cage for two years next to the portal in the captain’s quarters, though it hurt Gabrielle to see it so imprisoned and alone. Finally, after tiring of his constant complaining, she brought the cage on deck to give the poor thing a chance to see the sun. The mongrel dog growled, then whined for days, but Gabrielle did not notice. There the bird remained on days when it was fine, for another year, until finally, Gabrielle whispered to the bird that if he promised to return, she would let him out for an hour at sundown. The bird promised, and obeyed every day for ten days. But on the eleventh day, the red bird did not return to its cage.

The next morning, a mercenary’s ship approached from the north, and fired a shot into the starboard hull. It was their first hit since the crew’s meeting with Marguerite Belain eighteen years and nine months earlier. The ship listed, fought back, and barely escaped intact. Gabrielle stood on the mast step and peered through her spyglass to Martinique. A storm cloud churned and spread, widening over the thrashing sea.

Down in the ship’s hold, Gabrielle rummaged and searched until she found the empty rum barrel where she had placed the boats made of leaf and flower and moss, which she had fished out of the water when no one was looking. She took one, then thought better of it and took ten and threw them into the water. In the waning light she watched them move swiftly on the calm sea, sailing as one toward Martinique.

Gabrielle Belain (the witch, the revolutionary, the pirate) became the obsession of the Governor, who enlisted the assistance of every military officer loyal to him, every mercenary he could afford, and every captain in possession of a supply of cannons and a crew unconcerned about raising a sword to the child of a Saint Among Men. The third, of course, was most difficult to come by. A soldier will do as he is told, but a seaman is beholden to his conscience and his soul.

For many years, it did not matter. Ships sent out to overtake the ship with black sails, navigated and subsequently commanded by the girl with red hair, flanked as always by a mongrel dog, found themselves floundering and lost. Their compasses suddenly became inoperable, their maps wiped themselves clean, birds landed in massive clouds and ripped their sails to shreds.

In the beauty and comfort of the Governor’s mansion, I took the dictation of a man sick with rage and frustration. His hair thinned and grew gray and yellow by degrees. His flesh sagged about the neck and jowls, while swelling at the middle. As he recited his dictation, he moved about the room like a dying tiger in a very small cage, his movements quick, erratic, and painful.

When Gabrielle was a child and still living on the island, she was to the poor Governor an unfortunately located tick, a maddening bite impossible to scratch. When she boarded the pirate ship and gained the ear of a captain who was both a matchless sailor and ravenous for French gold, she became for the Governor an object of madness. He outlawed the propagation of redheaded children. He made the act of bringing fish back to life a crime punishable by death. He forbade the use of Gabrielle as a given name, and ordered any resident with the name of Gabrielle to change it instantly. He sent spies to infiltrate the wood surrounding the Pleasure House, but the spies were useless. They could have told him, of course, that Marguerite Belain went to the surf every morning to set upon the waves a small boat that sailed straight and true to the far horizon, though it had no sail. They could have told the Governor that every night a blue albatross came to Marguerite’s garden and whispered in her ear.

They told him no such thing. Marguerite instead led the spies into her home, where she fed them and gave them drink. Then, she led them to the Pleasure House. They would appear a few days later, sleeping on the road, or wandering through the market, examining fish.

The Governor, gesticulating wildly, dictated a letter to the king, asking for more ships with which to capture or kill the pirate Gabrielle Belain. He detailed the crimes of the pirate — twenty-five ships relieved of their tax gold, eighteen slave ships either freed or vanished altogether, rum houses raided, sugar fields burned — all these things I wrote to his satisfaction, confident that the king would, as usual, do nothing. In the midst of our audience, however, a young man threw open the doors without announcing himself and without apologizing. The Governor, sputtering with rage, threw his fist upon the desk. The young man did not stop.

“The black ship,” he said, “has been lamed.”

The Governor stood without breathing. “Lamed,” he said, “when?”

“Last night. They hailed the Medallion, who brought the message presently. They have taken refuge on the lee of St. Vincent. The injury to the black ship is grave and will take several days, I am told, to remedy.”

“And the ship who lamed it. Is it sound?”

“They lost a mast to cannon fire, but the ship, crew, and instruments are sound. Nothing lost, nothing.” The young man paused. “Strange.”

The Governor walked across the room, threw the doors open with such force that he cracked one down the middle. Whether he noticed or not, he did not acknowledge, nor did he take leave of me. The young man also left without a word. I laid my pages on the table and went to the window, the prayers for the intercession of the Blessed Mother tumbling from my lips. I stood at the window and watched as rumors of lightning whispered at the sky.

On the first of May, 1698, the ship with black sails was surrounded and beaten, its deck boarded and its crew put in irons. Messages were sent to the islands of France, England, and Spain that Gabrielle Belain (the pirate, the witch, the revolutionary) had been captured at last, and her execution had been duly scheduled. The citizens of Saint-Pierre brought flowers and breads and wine to the edge of the wood surrounding the Pleasure House. They lifted their children onto their shoulders that they might catch a glimpse of the woman who was once the girl who brought the fish to life, and who rode on the back of a porpoise, and who inherited the saintly, healing hands of her mother.

The day before Gabrielle Belain was to be executed, a large red bird visited the window, hovered on the sill, and kissed her mouth through the bars. This the people saw. This the people believed. In that moment, Gabrielle began to sing. She did not stop.

The Governor, as he welcomed representatives from neighboring protectorates and principalities, attempted the pomp and protocol befitting such a meeting. He heard the song of the girl pirate in the tower. His foreign guests did not, even as it grew louder and louder. The Governor rattled his sword, ran a shaking hand through his thinning, yellowed hair. He attempted to smile, as the song grew even louder.

The people in the market square heard the song as well. They heard a song of flowers that grew into boats that brought bread to hungry children. They heard a song of a tree that bore fruit for anyone who was hungry, of a cup that brought water to any who thirsted. She sang of a kiss that set the flesh to burning, and the burning to seed, and the seed to sprout and flower and heavily fruit. The people heard the song and sorrowed for the redheaded child, barely a woman now, who would die in the morning.

The song kept the Governor awake all night. He paced and cursed. He made singing illegal. He made music a crime worthy of death. Were it not for the celebrations planned around the scheduled execution of the pirate, he would have slit her throat then and there, but dignitaries had arrived for a death march, and a death march they would see.

In the moments before the dawn crept over the edge of the sky, the Governor consented that I would be allowed into Gabrielle’s cell to administer baptism, absolution, and last rites. Gabrielle stood at the window where she had stood all night and the previous day, the song still spilling from her lovely mouth, though quietly now, barely a breath upon her tongue. I offered her three sacraments, and three sacraments she refused, though she consented to hold my hand. I thought she did this to comfort herself, a moment of tenderness for a girl about to die. When the soldiers came to take her to the gallows, she turned to embrace me for the first time. She placed her mouth to my ear and whispered, “Don’t follow.”

So I did not. I let the soldiers take her away. I did not fight and I did not follow. I sat on the floor of the tower and wept.

Gabrielle, still singing, walked without struggle in the company of soldiers, all of whom begged her for forgiveness. All of whom told her stories of how her mother had saved a member of their family or blessed their gardens with abundance. Whether she listened, I do not know. I remained in the tower. All I know are the stories people later told.

They say that she walked with her eyes on the ground, her mouth still moving in song. They say she stepped up onto the platform as the constable read the charges against her. He had several pages of them, and the people began to shift and fuss in their viewing area. As the constable read, Gabrielle’s song grew louder. No one noticed a boat approaching in the harbor. A boat made of flowers and moss and leaves. A boat with no sail, though it moved swift and sure with a woman standing tall at its center.

Gabrielle’s song grew louder, until with a sudden cry, she threw her chained hands into the air and tossed her red hair back. A mass of birds — gulls, martins, doves, owls, bullfinches — appeared as a great cloud overhead and descended over and around the girl, blocking her from view. The Governor ordered his men to shoot. They did, but the flock numbered in the thousands of thousands, so while the square was littered in dead birds, the cloud rose nonetheless, the girl suspended in its center, and moved to the small craft floating in the harbor.

The Governor, his rage clamping hard around his throat and heart, ordered his ships boarded, ordered his cannons loaded, ordered his archers to shoot at will, but the craft bearing the two women skimmed across the water and vanished from sight.

This I learned from the people in the square, and this I believe, though the Governor issued a proclamation that the execution was a success, that the pirate Gabrielle Belain was dead, and that anyone who claimed otherwise risked imprisonment. Everyone, of course, claimed otherwise. No one was imprisoned.

That night, I stole gold from the coffers of the Abbey and walked down the road to the harbor. My beloved Abbot knew, I’m certain. The stores where such treasures are kept are always locked, but the Abbot left them unlocked and did not send for me after my crime. I purchased a small skiff and set sail by midday.

I am, alas, no sailor. My map, one that I copied myself, paled, faded, and vanished to a pure white page on the third day of my voyage. I dropped my compass into the sea, where it was promptly devoured by a passing fish. I have searched for a boat made of leaf, but I have found only salt. I have searched for two faces that I have loved. Gabrielle. Marguerite. The things I have loved. The scratch of quill to paper. The Abbot. France. Martinique. Perhaps it is all one. One curve of a wanton hip of a guileless god. Or perhaps my believing it is one has made it one. Perhaps this is the nature of things.

I do not know — nor, indeed, does it matter that I know — whether these words shall ever be read. It is not, as our beloved Abbot told me again and again, the reading that saves, but the writing: it is in the writing that the Word is Flesh. In our Order, we have copied, transcribed, and preserved words — both God’s and Man’s — for the last thousand years. Now, as I expire here in this waste of water and wind and endless sky, I write of my own disappearing, and this, my last lettering, will likely fade, drift, and vanish into the open mouth of the ravenous sea.

I have dreamed of their hands. I dream of their hands. I dream of a garden overripe and wild. Of a woman gathering the sea into her hands and letting it fall in many colored petals to a green, green earth. I dream of words on a page transforming to birds, and birds transforming to children, and children transforming to stars.

More Like This

A Secret Reverberates Across Four Generations of an East African Indian Family

Janika Oza fictionalizes her family's immigration story in "A History of Burning" to question complicity, safety, and belonging

May 12 - Rosa Boshier González

The Real Housewives of 16th-Century Scotland

Public spectacles of female conflict have long enforced social codes about male and female behavior

Nov 3 - Carissa Harris

The Daring Life of Philippa Cook the Rogue

"The Daring Life of Philippa Cook," from MANYWHERE by Morgan Thomas, recommended by Meredith Talusan