Books & Culture

The Portable Veblen Is a Delightful Synthesis of Psychological Study

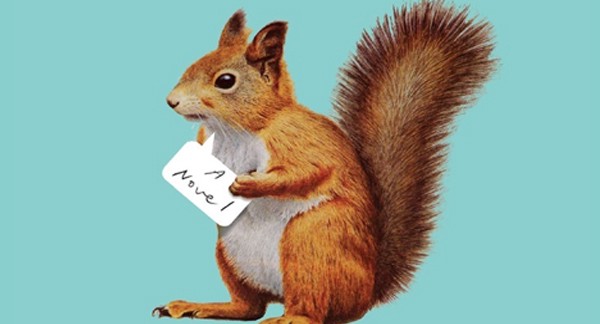

“It is one kind of trouble to kiss your fiancé goodbye in the morning and immediately turn your thoughts to another man,” muses Veblen Amundsen-Hovda, protagonist of Elizabeth McKenzie’s riotous sophomore novel, The Portable Veblen. “But it’s another kind altogether if the other man has been dead for nine decades, or is of the genus Sciurus.”

The man dead for nine decades: Thorstein Veblen, Norwegian-American economist and sociologist, ferocious critic of capitalistic materialism and coiner of the phrase “conspicuous consumption.” The creature of the genus Sciurus: one peculiarly tenacious and sagacious squirrel, with whom Veblen converses on a somewhat regular basis throughout the novel, and which proves particularly frustrating to her fiancé and the book’s co-protagonist, Dr. Paul Vreeland.

“Another kind altogether”: this novel, a delightfully knotty synthesis of psychological study, philosophical inquiry, romantic page-turner, and economic critique.

At its heart is the aforementioned “independent behaviorist, experienced cheerer-upper, and freelance self” Veblen Amundsen-Hovda. An amateur scholar of her namesake and Norwegian translator, Veblen gets by as a temp living a freewheeling life in a miraculously quaint bungalow right in the middle of the Siliconified Palo Alto. Freewheeling, at least, when she’s not helping her step-father manage her narcissistic hypochondriac mother, hitting the road to visit her PTSD-afflicted Vietnam Vet father in a psychiatric facility, or planning an impending wedding.

Enter Paul, the brilliant, Stanford-educated doctor and proud inventor of the “Pneumatic TURBO Skull Punch,” a medical device designed to help brain surgeons quickly and effectively treat traumatic brain injury by quickly cutting a neat hole through the skull. Straight-laced Paul is the rebellious product of a hippie family so devoted to his mentally disabled brother that Paul falls by the wayside. He is overjoyed to learn that the device has just been picked up by Hutmacher Pharmaceuticals, who plan to market it to the military and potentially make Paul a very wealthy man. His family, however, is not so thrilled — and for the Veblen-loving Veblen, it’s quite the philosophical hang-up.

In another novel (or ill-fated Zach Braff and/or Zooey Deschanel film), Veblen might be portrayed as the dreaded and dreadful manic pixie dream girl, and Paul the misguided good guy unsure how to secure her affections. McKenzie, thankfully, dashes that potential to bits. For one thing, instead of ending a love story with an engagement, she begins it with one, meaning the novel is filled with the aching anxiety of waiting for a wedding, rather than frivolous love.

For another, these characters aren’t just quirks for quirk’s sake. Veblen’s habit of talking to squirrels, living in her head, and avoiding traditional employment aren’t affected, but coping mechanisms, subconsciously constructed to help her manage a lifetime of being forced to mother her own mother. Yet they are aspects of her self from which she derives genuine joy — and why not? Can victims of trauma not find respite in its byproducts? Life is, after all, often that complicated.

For Paul, too, the desiring of stock portfolios and yachts, of fine, large homes and fancy dinners, is a reactionary response to his own damaging childhood. This is a man who, as a child, worried constantly of FDA raids of his family homestead, and who lost his virginity to a longtime crush after mistakenly inviting her over during one of his parents’ drug parties, during which they both unknowingly drank spiked punch. He is desperate to escape the “freedom” of the counterculture his parents indulged in and find normalcy and succes. Perhaps too desperate, as his stumbling venture into the corrupt world of corporate medicine and big pharma shows.

All of which is to say that The Portable Veblen is, in many ways, a novel about mental illness. The afflictions that Veblen, Paul, and their families confront have real emotional weight, even as they are dealt with more than a touch of manic humor. McKenzie’s prose has its precious moments, but they are more than made up for by her ear for the sound and flow of words. Like Veblen, the author shows a fascination with the specificities of flora and fauna to match that of the Romantic poets — not just squirrels, but “dark jelly newts” and Helix aspersa, “pale olive lichen” and a “handsome, muscular madrone.” And her deadpan send-ups of the outrageous marketing language of the medical economy — ”Corpsaire™ Sachet — Helps Eliminate Unpleasant Corpse Odors” — never fail to land.

At some moments, it’s hard to understand what brought Veblen and Paul together in the first place, and the novel’s rare moments of flat dialogue come when the narrative puts the most pressure on their conflicting ideologies. “You’re an awesome cook and a totally sexy, gorgeous woman,” Paul blathers in desperation after expressing frustration with Veblen’s impossible mother. “He was so transparent,” she thinks — a little too transparent, even for fiction.

But then you remember the commonalities. Paul may not be fond of the genus Sciurus, but he and Veblen are certainly both squirrelly: “crazy, nutty, weird.” And they work at love — truly work. Maybe that’s enough.