Books & Culture

The Problem with Pop Culture’s Love of Wrongful Conviction Narratives

Stories about innocent people being exonerated show the injustice of mass incarceration—but ignore that it's also unjust for the guilty

Wrongful convictions are a particularly American horror story. In no other country is the possibility that you might one day be incarcerated for a crime you did not commit such a pervasive and deeply entrenched part of the criminal justice system. In the United States, such convictions are not only possible but frequent. According to data from the National Registry of Exonerations, there have been more than 2,750 exonerations in the United States since 1989, adding up to a startling 24,596 years of life lost to wrongful imprisonment. In the past decade, 1,447 men and women have been released from prison on the grounds that their conviction was false, reaching a peak of 181 exonerations in the year 2016 alone.

In recent years, countless television shows, movies, and podcasts have taken on the problem of wrongful convictions. Shows like For Life on ABC, Proven Innocent on Fox, and the Innocence Files on Netflix all center around the stories of men and women serving time for crimes they did not commit. Films like Just Mercy and Trial by Fire, as well as the popular podcast In the Dark, also focus on wrongful convictions. As more and more people begin to grapple with the crisis of mass incarceration in the United States, it makes sense that stories of wrongful conviction would capture the lion’s share of our national attention. Wrongful convictions are perhaps the most blatant example of the cruel, unreliable, and racist nature of our broken criminal justice system. They also make for unquestionably good entertainment, offering readymade narrative arcs filled with all the drama, suffering, and human redemption that audiences crave. These stories provoke necessary outrage in viewers as much as they inspire hope. At their center is the innocent hero who stoically endures unimaginable hardship only to emerge, often decades later, resilient, triumphant, and free.

Stories of innocence and exoneration are undeniably important. But they are not the only stories that need to be told.

At a time when many Americans are coming to see policing and prisons as pressing social ills that must be seriously reformed and reimagined (if not outright abolished), stories of innocence and exoneration are essential. Exoneration narratives shed light on the startling number of false convictions plaguing our criminal justice system and bring renewed attention to the junk forensic science, institutional racism, and rampant prosecutorial misconduct that allow a wrongful conviction to happen in the first place. They can even build public momentum behind high-profile cases that might one day result in exoneration and release. Exoneration narratives encourage viewers to question the long-held belief that our criminal justice system is a finely tuned machine that functions without bias, discrepancy, or flaw. They are undeniably important. But they are not the only stories that need to be told.

Starting with the podcast Serial in 2014 and the Netflix series Making a Murderer the following year, exoneration narratives have perhaps been the dominant story we’ve told about the criminal justice system for over half a decade. The popularity of Serial and Making a Murderer paved the way for an impressive number of other shows, films, and podcasts centering on wrongful convictions. The 50-Cent produced ABC drama For Life, which premiered in February of 2020, is based on the true story of Isaac Wright, a Black man who was sentenced to life in prison under New Jersey’s punitive drug kingpin laws. While incarcerated, Wright became a prison paralegal, representing many of his fellow prisoners and eventually getting his own sentence overturned, a reversal that rested largely on the testimony from a police officer who admitted to misconduct. The podcast In the Dark explores how racism in jury selection and the highly questionable conduct of District Attorney Doug Evans and lead investigator John Johnson kept Curtis Flowers on death row at Parchman Prison for 22 years. Ava DuVernay’s 2019 Netflix limited series When They See Us focuses on the Central Park 5, paying special attention to the infamous prosecutor Linda Fairstein, whose tough-on-crime carceral feminism helped send five innocent young Black boys to prison. Documentaries like The Innocence Files, also on Netflix, have helped to counter the prevalent “CSI effect,” or the misguided belief created by popular TV shows and movies that police officers solve rapes and murders swiftly, easily, and without error. Produced by esteemed documentarian Alex Gibney, this nine-part series slowly dispels that myth, showing the ways that debunked forensic science, unreliable witness testimonies, and deeply entrenched prosecutorial misconduct have been sending innocent people to prison for decades.

Insidiously built into the exoneration narrative is the argument that while the innocent person clearly should not be in prison, everyone else should be.

There is a problem, however, with framing mass incarceration solely as a matter of guilt versus innocence. Mass incarceration didn’t happen because the United States imprisons too many innocent people. One wrongfully convicted person is, of course, too many. But the real problem is that the United States incarcerates far too many people, period, and incarcerates them for far too long. The truth is that most people incarcerated in the United States today have indeed committed crimes, often very serious ones. This does not make their incarceration just. Even if the United States released every person with a valid innocence claim from prison today, we would likely still be the most carceral country in the entire world.

Most mainstream exoneration narratives, especially those on cable TV, seem progressive but are in fact only progressive up to a point. In reality, these shows, movies, and podcasts do not question the whole system of mass incarceration but rather focus on the obviously broken part of that system that allows the innocent to languish in prison while the guilty go free. Insidiously built into the exoneration narrative is the argument that while the innocent person clearly should not be in prison, everyone else should be. While vindicating the innocence of the wrongfully convicted, these narratives can also work to reaffirm the inherent guilt and badness of the incarcerated men and women who did indeed commit the crimes they are incarcerated for.

Exoneration narratives often do very little to question the overall efficacy of extreme prison sentences or explore the various societal factors, including lack of access to meaningful employment, education, or mental health services, that might lead someone to commit a crime in the first place. Stories like For Life, In the Dark, and the Innocence Files seldom reckon with any of the major drivers of mass incarceration, such as the omnipresence of tough-on-crime political rhetoric or the rise of harsh sentencing legislation. While these stories succeed in portraying the daily brutality and inhumanity of prison life, their critique is often limited. In many popular exoneration narratives, the horrors of incarceration are portrayed as horrors only for those we have been deemed innocent of their crimes, not for all people who must suffer behind bars. Mass incarceration will continue in this country until the United States rolls back its discriminatory and excessively punitive sentencing regime and begins to see incarcerated people not as intrinsically dangerous criminals who should be condemned to perpetual punishment and suffering but as human beings who deserve a shot at redemption.

What new stories can we tell about how and why our country punishes both the innocent and the guilty? How can we start to trouble the concept of ‘guilt’ itself?

Adnan Khan, an activist for Re:Store Justice, has denounced the presence of true crime stories in pop culture. On the night of Brandon Bernard’s execution in December, Khan tweeted, “I swear these crime shows and podcasts have perverted the hell out of society’s mind and worse, their hearts. The death penalty isn’t about the intricacies [of a] person’s case or even what they’ve done. It’s about the morality of society and our heartless need to kill people.” Khan served sixteen years in prison under the felony murder rule and has since become a vocal advocate for all incarcerated men and women through his work at Re:Store Justice. As Khan notes, podcasts like Serial take a purely procedural approach to their stories, turning listeners into investigators who can use the carefully presented evidence to decide for themselves who committed the crime. By viewing crime through a solely procedural lens—did they or didn’t they do it?—these stories all too often fail to reckon with the morality of excessive punishment itself.

We have always consumed stories of innocence with fascination and rage, especially when the innocent person is white. Think about Amanda Knox, or Andy Dufresne from the Shawshank Redemption. As we continue to watch, listen to, and read about wrongful convictions, it is important to ask ourselves whether this new wave of stories represents an evolution in our thinking about the criminal justice system or is simply maintaining the status quo. How can we further expand our understanding of mass incarceration in ways that work to dismantle the system as a whole? What new stories can we tell about how and why our country punishes, confines, and all too often kills both the innocent and the guilty? How can we start to trouble the concept of “guilt” itself?

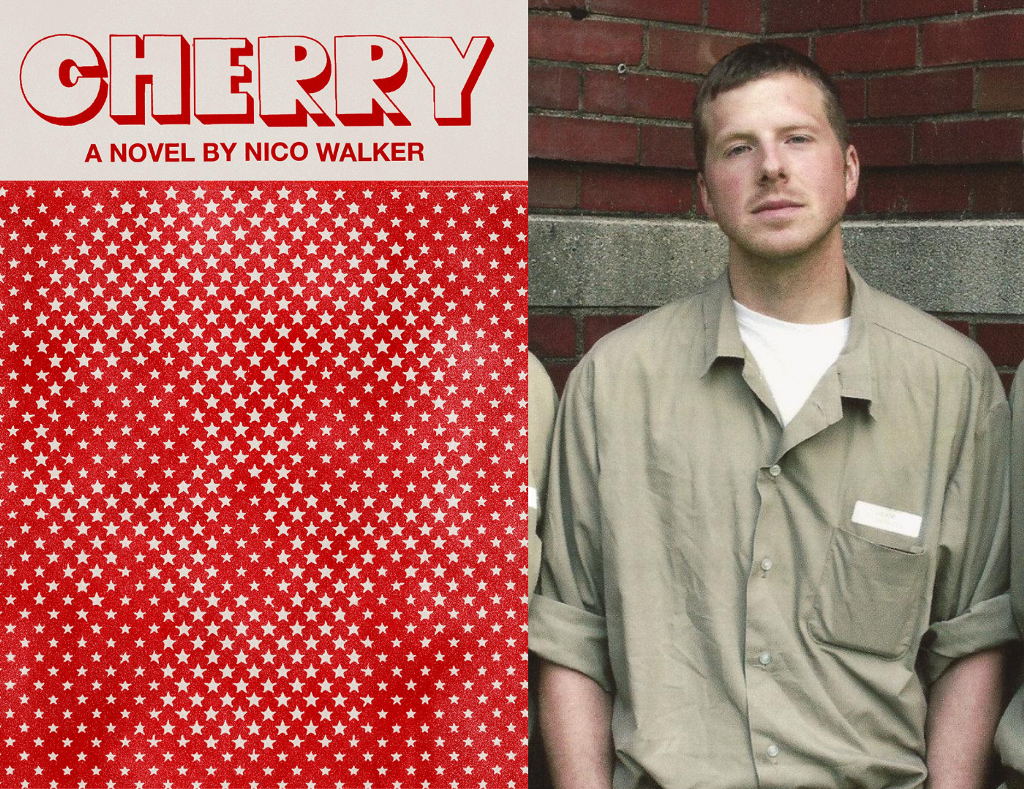

While there has always been at least some necessary fear and outrage about wrongful convictions, we have yet to see many mainstream stories where a truly “guilty” person is given the complexity and deep humanity that exoneration narratives give the innocent. Individuals who have committed serious crimes should obviously be held accountable for the harm they have caused, but society is doing itself a grave disservice when we continue to portray these individuals as irredeemable monsters who can only be stopped by a life sentence or worse. Shows like Orange is the New Black and The Wire, documentaries like The 13th, movies like Claire Denis’s death-row-in-space drama High Life, poetry collections like Felon by Dwayne Reginald Betts, and novels like the Mars Room and Riots I Have Known are a great start, but we can go further. We need more movies, television shows, documentaries, and podcasts showing that the “criminals” our country has long taught us to hate and fear are in fact complex human beings with the capacity to grow, change, and make amends. One does not surrender their humanity at the prison door. Furthermore, we must make space for more directly impacted people to tell their own stories about the criminal justice system, regardless of their crime. Elevating these kinds of stories will complicate our understanding of violence and help us to view crime in a more complex and morally nuanced way, not as the result of some intrinsic evil or corruption but often as the result of larger societal problems—economic deregulation, generational poverty, systemic racism, the shrinking social safety net, toxic masculinity, the legacy of trauma and abuse, and so on—that a prison sentence will never cure. We might even learn that we are culpable too.

Mass incarceration is of course a problem of policy, but it is also a problem of storytelling.

If ever we have needed a reckoning with our system of punishment in the United States, it is now. More than 380,000 incarcerated men and women have been infected with the coronavirus since the start of the pandemic. Over 2,300 of those people have died, as have more than 190 prison staff members. What’s more, thanks to harsh sentencing laws and ineffective clemency processes, our prisons are filled with men and women over the age of 55, the demographic most vulnerable to the coronavirus. Though most of these men and women no longer pose a threat to society, they remain behind bars. More of them will die before the pandemic ends.

Mass incarceration is of course a problem of policy, but it is also a problem of storytelling. We desperately need more stories that counteract our deep-seated collective belief in the value of punishment and that show the humanity and complexity of all incarcerated people. By focusing so much of our recent storytelling on wrongful convictions, we have neglected many larger questions. This isn’t to dismiss or discredit the incredible value of exoneration narratives but rather to encourage more writers, filmmakers, and creators to expand beyond this limited framework. Our entire criminal justice system is broken, for the innocent and for the guilty. Let’s start telling that story too.

Correction: This piece originally conflated activist Adnan Khan with Serial subject Adnan Syed.