Books & Culture

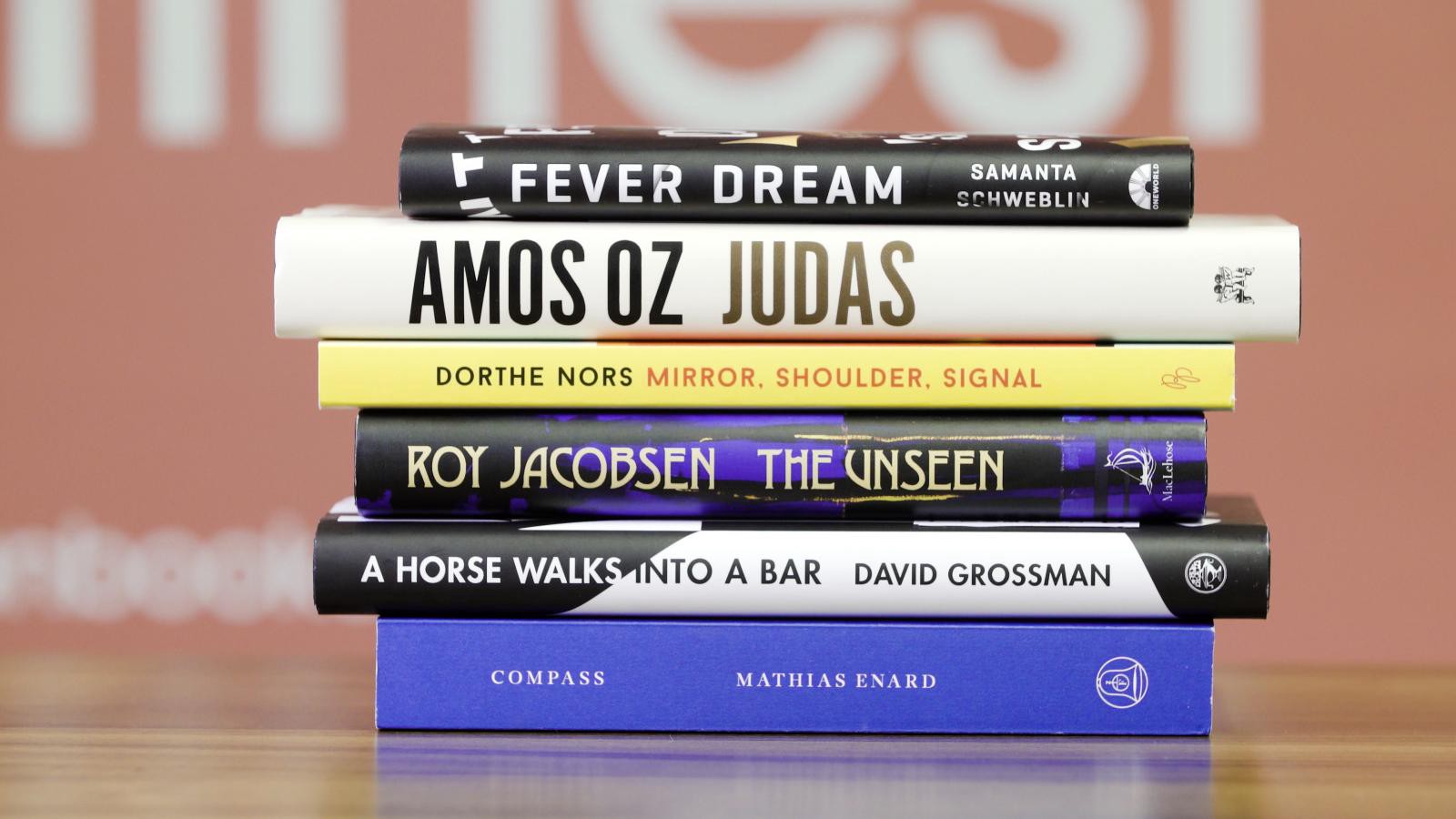

The Queer Erotics of Handholding in Literature

Physical touch in the novels of Patricia Highsmith and Sarah Waters

People always want to know how queer love functions, but that question feels unanswerable. If books have taught us anything, it’s that there’s no right way to love a body. I’ve had people ask how I know a woman wants me. They want some lesbian strategies, a set of documented rules. They ask: how did female friendship miraculously transform into love?

How should I know, I want to say, shrugging off the thing that might trap me. How should I know any of it? I’ve only ever really held hands once and look how that turned out.

‘She thought of people she had seen holding hands in movies, and why shouldn’t she and Carol?’

Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt provides readers with countless glimpses of queer hands. The novel documents the burgeoning relationship between Therese, a young woman working at a department store, and the much older object of her affection, a soon-to-be divorcée named Carol. It’s a novel about two women falling in love. It’s the story of how queer attraction sometimes functions: in closeted spaces, coaxing emotions that are difficult to navigate. These liaisons, born in secret, are often fraught with anxiety. For lesbian relationships in the 1950’s, there are no rules for knowing what shouldn’t exist.

Much of Therese and Carol’s attraction is documented through touch. Hands crop up incessantly throughout The Price of Salt: they perform domestic duties and work unwanted day jobs, they pilot cars and open motel doors. More importantly, they’re viewed through the eyes of a woman looking for romantic signals. Therese watches Carol’s hands as they move and perform. Carol’s hands become the impetus for the erotic. As readers, we’re shown their significance through the lens of Therese. She watches Carol’s hands like she might watch a barometer. By viewing what the hands do, she’s able to ascertain what is wanted from her. Do the hands coax? Are they pushing Therese away; are they standoffish and flighty? A fundamental element of eroticism is the tension of what might be. We understand Therese’s longing as it pertains specifically to Carol’s hands.

In the novel, Therese wonders why she can’t achieve a simple moment of intimacy, the kind heterosexual couples achieve without having to overthink the act. Holding hands is considered a rite of passage for most people. Palms pressed together, fingers interlaced. It’s a sweet, uncomplicated way to move a relationship from friendship into something more.

For lesbian relationships in the 1950’s, there are no rules for knowing what shouldn’t exist.

“…why shouldn’t she and Carol?” muses Therese, who considers what it might mean to walk hand-in-hand with the person she loves. Handholding. It happens in movies and on the street, casually reaching for the hand of the person you want. People do it all the time.

But considering queer female sexuality, touching hands is illicit. For lesbians it often marks the entrance into what might happen next in an erotic sense. Queer women assess hands in terms of their readiness for sex: the length of someone’s fingernails, the strength in their grip. We look at hands to see if they’re up for intimacy. Our hands do the work of sexual organs.

What would happen if we touched, we wonder. What would happen if my hand found yours? What would come next?

Highsmith, a queer woman, knew this. In 1952, she had to write her novel under a pseudonym or risk tanking her career. There was no lesbian writing available for mass-market publication at that time. No place for queer female romance in the strictly heteronormative audiences that populated mainstream fiction.

We look at hands to see if they’re up for intimacy. Our hands do the work of sexual organs.

Publishers were unwilling to take on the novel. It was farmed out to a smaller house and ultimately picked up as pulp. The book’s cult following, mostly queer women, gained momentum over the past decade. The tender, anxious relationship that blossoms between Therese and Carol showcases the stress of coming out for women in a time period where they were expected to marry men and maintain households. Not so many years ago, the simple act of touching another woman’s hand meant you might have to give up everything you knew for love. Concerned with documenting that struggle, The Price of Salt turns handholding into a marker of queer rebellion.

The first time I held a girl’s hand, I thought about it so hard beforehand I made myself throw up. It was an anxiety so all-consuming that I puked three times. A rocketing kind of barf; the kind that made my guts want to exit my body, exorcist-style. My mother, normally someone who made me suck a thermometer for twenty minutes before she’d let me stay home, took one look at my face and called me in sick for school. Rolling around in my bed, I twisted the sheets and prayed something might give. Things I worried about:

How I’d reach for this girl. How she’d respond.

What my fingers would do. Would my thumb go on the outside? Inside?

Would my palms sweat? Would I tremble?

The first time I held a girl’s hand, I thought about it so hard beforehand I made myself throw up.

Most of all, I wanted to know where holding hands would eventually lead: because if I held her hand, my hand might then touch her wrist, her shoulder, and then her breast. We were very young and good friends and neither of us had dated before. There’d been no discussion of romance because neither of us was “that way.” Every step toward this new part of our relationship existed in how she brushed my hand when we passed a can of coke between us during choir practice. Every pass of the can left her fingers on mine until we were touching each other more than the soda. I liked the way she held the high notes. I drew caricatures of her face in my vocal scores. High A, high A: a beautiful second soprano who made the notes sound like clear, ringing bells. I was a first alto. Nobody cares about that vocal range.

I asked her to a movie, just the two of us. She said yes.

“This doesn’t mean anything,” she whispered as we sat in the darkened theater. I couldn’t watch the movie. I closed my eyes and thought about her hand. The webbing of her fingers pressed hard enough against my own to form a seal. “It doesn’t mean anything,” she repeated as she stroked the inside of my palm with her littlest finger.

Handholding is a trigger for the wider issues of the erotic. In The Price of Salt, Therese considers the action a relationship-defining event. Once the hands grip, there’s no turning back. It’s the line in the sand. The action changes the relationship into something denser; the pressure like smashing coal into a diamond.

‘It doesn’t mean anything,’ she repeated as she stroked the inside of my palm with her littlest finger.

I don’t like the dictionary definition for hands. It’s all metatarsals and bone fragments, so clinical it removes the movement from the parts. But what I do like of the definition comes from the secondary source. We’re told that a hand can be considered a personal possession; that to “hand” something means you have given someone an instance of control or supervision. The example provided:

left the matter in her hands

To leave matters in someone’s hands means they maintain autonomy over their actions and their desires. The Price of Salt repeatedly provides images of hands that chart the course of their owner’s lives. I read these sentences and think of the hands that have touched me, certainly, but mostly I think of my own hands and what they continue to do. Holding a beer, peeling the wet label from the bottle. My fingers scratching behind my dog’s ears. One long ago summer, I wet my palms with lake water when I went on a trip with that first girl I loved, the one who only acknowledged my presence when we were alone. When we swam, I held her buoyant above the drifting algae. Her body felt insubstantial and I gripped harder just to know she was present; just to know she was there with me. At that point in my life, queer hands were only allowed to touch when no one else was looking.

“This doesn’t mean anything,” that same girl said in the theater as she stroked my palm, but what she meant was:

It only means something to you because I won’t let it mean anything for me. If exposed to air and light, my hands will untangle themselves from yours.

Highsmith looks at hands in The Price of Salt as conduits for future intimacy. She showcases them as what-will-come. I often look at hands as objects of desire and self-ruination.

Control, supervision. The matter is left in my hands.

The movie version of Highsmith’s book, Carol, often puts the camera’s focus on character’s hands. Gauzy close-ups of Carol’s fingers as she smokes cigarettes. Hands caressing the soft, peachy fuzz of women’s faces. Fingering fabric and carting around purses, grasping at the straps. Holding onto drinks. Women are always clutching alcohol in these scenarios, as if to do the work they need to do, the hands must first be inebriated. Highsmith writes about hands in ways that suggest the erotic and the romantic, but as separate entities. Though the book has an unheard-of happy ending for its time, it’s also one of the first queer books I read where sex doesn’t necessarily mean love. For queer love to exist in much of literature, it must be shown in mortal agony. People want to see it born so they can watch it die.

For queer love to exist in much of literature, it must be shown in mortal agony. People want to see it born so they can watch it die.

In the grand tradition of lesbian novels, there’s always the reveal of the emotion and the quick killing off of one of the women. Lesbian love doesn’t often survive written scenarios or even many movie scenes. The Price of Salt is different. Highsmith allows for the pain of losing a straight, heteronormative life, but she leaves the two women intact at the end of it. In her novel, the erotic focuses less on romance and more on who’s in control of the relationship: “I feel I stand in a desert with my hands outstretched, and you are raining down upon me.”

Hands are used to mark instances of scarcity and plenty. They’re always reaching out; to touch something, anything, to embrace another person so they know they aren’t alone. Touch in these instances moors the characters in space and time.

The Price of Salt might use hands to mark discovery, but I use hands as warning signs. I keep them outstretched, like a person searching a darkened room. I want them as barricades. It would be nice to find things, sure, but I don’t want anything finding me.

…to obtain information about the texture of an object, people rub their fingertips across the object’s surface, and to obtain information about shape they trace the contour of the object with their fingertips. Conversely, in object manipulation there is precise motor control of the hands. The fact that individuals with numbed digits have great difficulty handling small objects even with full vision illustrates the importance of somatosensory information from the fingertips.

Encyclopedia of the Human Brain, Vol 2

In the span of a day I count 494 separate hands. This number is an instance of a single day. It’s a pastime I perform repeatedly; something I do without thought. I look at people’s hands and note them, checking them off. Everyone’s hands. As a librarian, I see patrons pick up books, palming library cards, clutching overdue receipts. Fingers flipping through pages. Rifling the newspapers. I watch the way people hold their belongings and shoulder their backpacks. I note the value they place in their things and the garbage they toss without thinking. I count hands the way someone might count sheep.

Though I shy away from friendly intimacy like hugging, but I’m fascinated by what fingers and thumbs and palms can do. Dexterity. Manipulation. The movement of our speech so often contained in the movement of our hands. Mine are birds when I speak, flapping until I ascend and reach the apex of my sentence. When I’m stressed, I move my fingers like they’re gears that power the momentum of my thoughts. Help me reach the point, I beg, as they open and fold and smack into each other.

Dexterity. Manipulation. The movement of our speech so often contained in the movement of our hands.

Highsmith wants the reader to know queerness in terms of the other. The other, in this instance, is anyone aside from the two women and their relationship. Their magnetized bodies are what draw us close to them as they draw close to each other. We want to know: why do they feel the way they feel? We want to know because no one understands these impulses. We want to know because our bodies want unknowable things and most of the time our brains can’t understand why.

We see the body here, broken up into parts. The eyes. The voice. Most of all the hands, which Highsmith uses for directional control. Touch is the thing that binds the characters. Touch is the thing that maps the body. In the novel, it’s a driving impulse. But we understand this as readers because we are that way ourselves. How do we react in moments of pain? Of fear? Of intense need? We stretch out our hands. We reach for the unreachable thing. We ache and want. We grasp.

‘You ask if I miss you. I think of your voice, your hands, and your eyes when you look straight into mine.’

It’s said that fingers contain some of the densest areas of nerve endings on the body. If I drink, I can numb my brain and also the sensitivity that comes from touch. How hard is it to orgasm after three beers. Four? Five beers in and my hands could be touching the smooth, warmed-over flesh of a melon. In those buzzed moments, every time I touch something I am touching it for the first time.

Could hands address the same issues over and over again without knowing? Do hands hold amnesia cupped in their palms? How else do we describe the illusion of seduction. Even when we’re touching ourselves, we’re inventing scenarios for our hands to chart. We imagine the hands as belonging to other people. We imagine those hands are capable of things far beyond their potential.

We can use our hands not only to manipulate the physical world, but also to perceive it. Using our hands to perceive the shape of an object often involves running the fingertips over the object’s surface. During such ‘active touch’, we obtain both geometric and force cues about the object’s shape: geometric cues are related to the path taken by the fingertips, and force cues to the contact forces exerted by the object on the fingertips. These cues are highly correlated, and it is difficult to determine the contribution of each to perception.

Nature, Vol 412, 26 July 2001

In the aptly named 2002 novel Fingersmith, Sarah Waters discusses queer hands in the same way Patricia Highsmith does. A work of historical fiction, Fingersmith is concerned with the lives of two women: Sue, an orphan who’s been sent to gain the trust of Maud, a wealthy heiress. Waters narrates from both female perspectives throughout her book. In the first instance, we’re given narrative from Sue, posing as a lady’s maid, who has set out to manipulate Maud. Sue eventually falls in love with Maud, much to her dismay. In the second part, we’re given the perspective of Maud, who’s got her own agenda. Both sections of the book deal with the improbabilities of love and honesty, and both scenarios demarcate what it’s like to discover something unexpected with your hands.

In Waters’ books, bodies discover love ahead of the conscious mind. But again, the bodies are the ones leading the charge. The characters bodies are often tools for the protagonists to enforce their will. They find love with their hands before their hearts are willing to acknowledge any kind of true intimacy. Sex is a power dynamic. Sex is ruled with the hands.

“Do you know how careful my love will make me? See here, look at my hands. Say there’s a cobweb spun between them. It’s my ambition. And at its centre there’s a spider, a color of a jewel. The spider is you. This is how I shall bear you — so gently, so carefully and without jar, you shall not know you are being taken.”

Waters makes these bodies open and accessible to the reader. Yet at the same time, their minds are closed. Both women seek ways to understand. They forsake each other, again and again, but their hands always do the most honest work. Even when they can’t admit they love each other, their hands say it for them.

Even when they can’t admit they love each other, their hands say it for them.

Their hands draw a pleasurable agony. It is the most understandable kind of pain.

I like hands the way I like knowing the exact right thing to say in a conversation. How they open and shut, how they fold into themselves and hide things. I want hands the way I want to know my own mind. I want them with a fierce, unknowable throbbing. Once very late at night, a friend asked what part I liked most of a body. We’d been talking about sex for hours and I’d spoken without flinching: orgasms, one-night stands, documenting our best sexual experiences and our worst.

What part do you prefer, that friend asked, and I replied:

“Hands.”

My voice was so unsteady I could hear the ache in it. I looked at that friend’s hands when I said it and swallowed hard. An entire night discussing sex and the red flush only crept up my neck when I thought about those parts that inevitably do all the touching. The part that precedes my brain; that shows all my want. The part I can’t hide from myself

Forget toolmaking, think fisticuffs. Did evolution shape our hands not for dexterity but to form fists so we could punch other people?

— New Scientist, 19 December 2012

In hands, power sometimes means violence.

Even when we’re touching ourselves, we’re inventing scenarios for our hands to chart. We imagine the hands as belonging to other people.

There is sex happening with hands in these narratives, certainly, but there’s also fraught emotion — a love that hinges on manic.

Unlike Highsmith, Waters’ novel looks at how two queer storylines might eventually intertwine to show how bodies function within the construct of aggression. There is sex happening with hands in these narratives, certainly, but there’s also fraught emotion — a love that hinges on manic. Too stressful to be dealt with outright, the sex and the intimacy become a kind of ownership. Revisiting that secondary definition of hands, we see the word control. What are the hands doing if not guiding the other into the role they wish them to play?

“…but when she saw me turn to her she reached and took my hand. She took it, not to be led by me, not to be comforted; only to hold it, because it was mine.”

Hands in traditional feminine roles perform “women’s work.” They guide the domestic. They’re the hands that carry babies, create meals, that clean and maintain households. Capable hands. As a person who grew up in a space where gender roles were rigidly enforced, I look to these domestic spots and wonder how to reimagine them. One way of doing that is in how I think about art outside of writing.

When I make things for friends, I use my two hands. I’ve sliced myself and blood has wet these created objects. Bits of me — my hair, flakes of my skin — inevitably embed in the work. Fragments of my body make their way from me, through the mail, and into the person’s home. My fingers ache when I’m done. It’s a reminder that I used the tenderest part of me to engineer something they open and touch. That part of me, that building part, will always be with them. Let my hands do the talking, I plead with these gifts.

It’s not unlike how I perform sexually. Just let me show you what these hands can do, I say.

As a perceptual organ, the hand has several advantages over the eye: the hand can effectively ‘see’ around corners and can directly detect object properties such as hardness, temperature and weight. During active touch, the perceptual and motor functions of the hand are tightly linked, and people tailor their hand movements to the information they wish to extract. Whereas ‘local’ information about the object, at the fingertip’s point of contact, can be extracted simply by touching the surface.

Nature, Vol 412, 26 July 2001

When I was young, I bought a hand strengthener from the dollar store because I wanted to be able to fend for myself. I was seventeen and my hands, dangling from my skinny, praying mantis frame, looked inordinately large for my body. The strengthener, I thought, would help me achieve some measure of control. I wanted to be the one someone turned to when they needed something.

Correction:

I wanted to be the one that women turned to when they needed their sodas opened. So I bought the hand strengthener and used it every night in my room, clenching down on it over and over again until my repetitions beat into the backdrop of the sad, lovelorn music that played on my stereo. I’d cut off all my hair that summer and bought men’s cargo pants. I wore a sweater vest and oxford brogues and my mother wouldn’t let me leave the house because she said I “looked to much like Ellen.”

The girl I first loved told me she liked my shoes and she liked my pants and her hair was longer than anyone I knew. When we held hands, finally, I took hers gently and tried not to crush her fingers with my own. My hands were strong enough by then I could’ve hurt her. I didn’t want to crush her. I wanted only to show tenderness.

“This means nothing,” she said in that movie theater, but I let my hands cradle hers like baby birds. It was important that I show the utmost delicacy. Tenderness was foreign to me. I wanted her to know I could love without hurting someone.

Therese thinks logistically in The Price of Salt about how her hands work in conjunction with Carol’s hands. She’s always at odds with them just as she’s always at odds with her own feelings. The characters emotions are so overwhelming that her body works against her mind’s wishes most of the time.

“Therese leaned closer toward it, looking down at her glass. She wanted to thrust the table aside and spring into her arms, to bury her nose in the green and gold scarf that was tied close about her neck. Once the backs of their hands brushed on the table, and Therese’s skin there felt separately alive now, and rather burning.”

Handholding with the girl I once loved made me feel like my skin was being slowly peeled from me. I remember that when we kissed it was something good — but it was handholding, that precursor to the other kinds of holding, that made my insides ache. Her hands and how they touched mine let me know how they might touch other parts of me. Those parts, alive with nerves and singing, singing, refused to let me forget what they could do.

Handholding with the girl I once loved made me feel like my skin was being slowly peeled from me.

Highsmith writes that Therese thinks about the desire to “thrust” and “spring” at Carol. The imagined actions are followed closely by the real action — the tender brushing of the backs of hands against a table. That bare contact is enough to send Therese into agony.

Hands function in Highsmith’s text as conduits. They are grappling objects, passing across each other’s skin only to alight the flesh with “burning.” Hands work frantically to conjoin bodies. Perhaps that’s the thing that brings the erotic to the forefront of the mind when we consider queer hands: the fact that they indicate what might happen next. Unlike most queer stories, which focus on bringing the hidden to light (coming out narratives), Highsmith and Waters’ hands are all about possibility. They’re already out. They’re actively seeking.

I love you, they say, but don’t hold too tight. Gently. Don’t crush me.

The woman who would not recognize me outside our theater-darkened handholding let me touch other places on her body. Understanding of my own frame hinges on a complex understanding of hers. Handholding. Heartholding. It was a body I knew under the scope of my palm.