Interviews

The Refugee Woman Who Shaped Brazilian Literature

A long-awaited translation of Clarice Lispector’s second novel, ‘The Chandelier’

Sometimes, people appear in the fabric of a country’s history as an inexplicable aberration. It seems to be the only way to explain Clarice Lispector and her monumental rise as perhaps the most influential writer of 20th century Brazil.

In 1921, as a one-year-old, Lispector came to Brazil with her family as a refugee, fleeing pogroms in war-torn Ukraine, only to become one of the country’s most revered, mysterious, and beloved authors. As Lispector was working on her first novel, Near to the Wild Heart, which was published in 1943, her fellow journalist and friend, Francisco de Assis Barbosa noted that, “as I devoured the chapters the author was typing, it slowly dawned on me that this was an extraordinary literary achievement.” He guided the manuscript towards a publisher and gave her the inimitable nickname, “Hurricane Clarice.” But Lispector’s second novel, The Chandelier, couldn’t have been received more differently: publishers rejected it, and, upon release, the book was considered so strange and inscrutable that it was largely ignored and forgotten, so much so that Benjamin Moser and Magdalena Edwards’ new translation of The Chandelier is its first ever into English.

Though Lispector has been a fixture in the Portuguese-speaking world for decades, she has long been neglected and poorly translated for English-speaking audiences. Over the past nine years, however, she has received a steady revival: a major biography, a first-ever collection of her complete short stories, and the steady retranslations of her novels by New Directions Press, led and edited by critic and biographer Benjamin Moser. Part of Lispector’s appeal is her unique identity as both a part of and apart from Brazil, from her unusual last name to her heavily accented Portuguese, a separateness that let her succeed in a culture and country prohibitive to women. She was one of the first Brazilian women to graduate from law school, and also one of the first to become a journalist.

Lispector’s unique identity as both a part of and apart from Brazil lets her succeed in a culture and country prohibitive to women.

Her name also helped build her famously mysterious allure — when her first novel was published, rumors flourished that her unusual name was actually as pseudonym for a man. Her mystery and mysticism is borne out in her writing, which is as wonderful as it is peculiar, emotive, and sometimes impenetrable: “from the high windowpanes one saw, beside the garden of tangled plants and dry twigs, a long stretch of land of a sad and whispered silence.” Or, when one of her characters is sitting in her apartment and writing letters to her family, she finds that “no, it wasn’t unhappiness that she was feeling, unhappiness was a moist thing on which someone could feed for days and days finding pleasure, unhappiness was the letters.” In drawing comparisons, she is often compared to James Joyce or Virginia Woolf or even Franz Kafka, but her style is one that, in the Portuguese language, is still considered singular and, at first, felt considerably “foreign.”

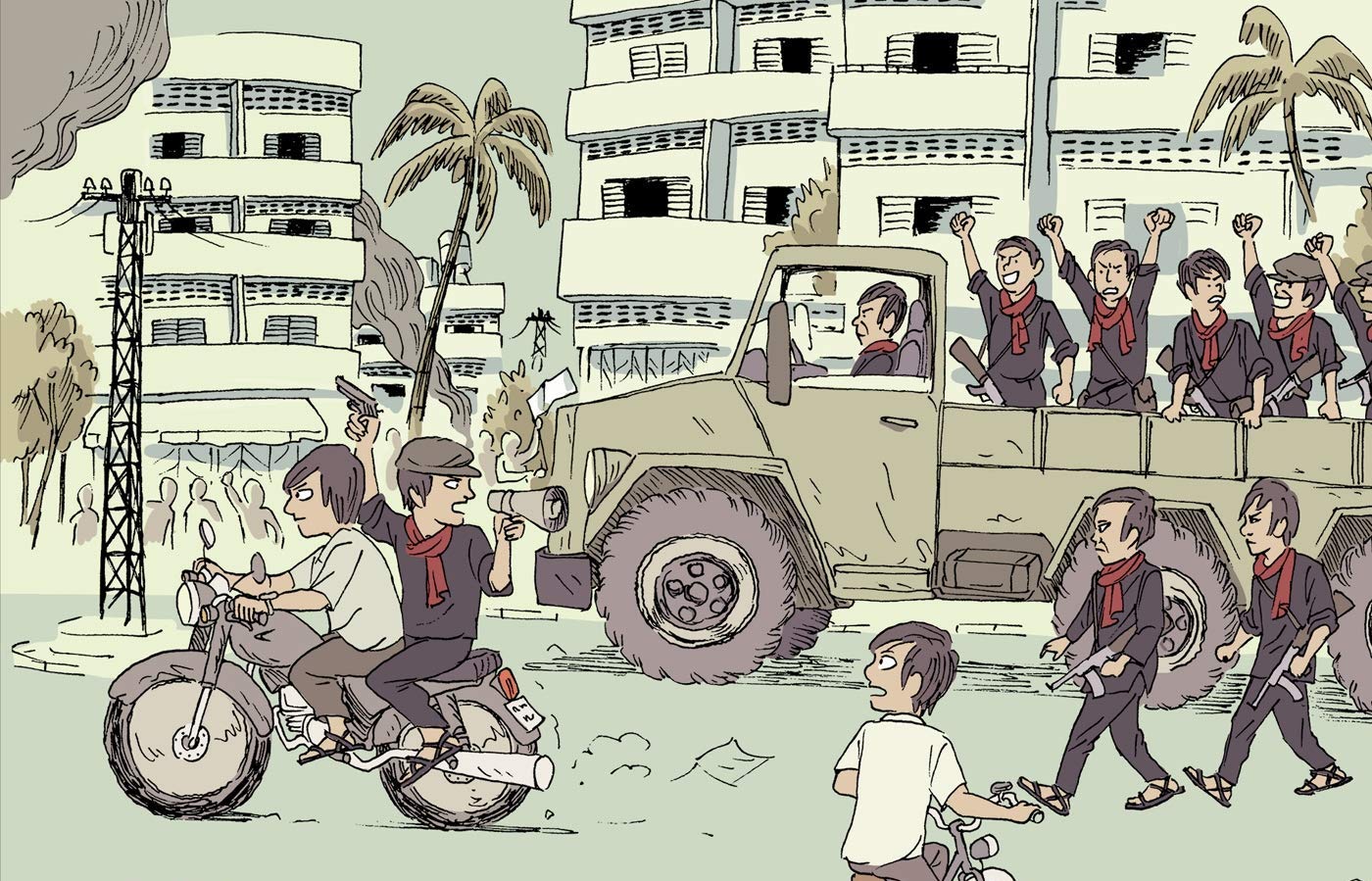

If she were of our current moment, Lispector might be best identified as a “Dreamer” or asylum seeker — when she turned 21, under the threat of being deported to Russia as a Jewish woman during the height of World War II, she appealed directly to Brazil’s infamous dictator, Gertúlio Vargas, saying she was: “a twenty-one-year-old Russian who has been in Brazil for twenty one years minus a few months. Who does not know a single word of Russian but who thinks, speaks, writes, and acts in Portuguese. . .Who, if she was forced to return to Russia, would feel irredeemably foreign there, without a friend, without a profession, without a hope.”

If she were of our current moment, Lispector might be best identified as a ‘Dreamer’ or asylum seeker.

Her petition was successful, and this good fortune, among the stability of a then-supportive marriage, and a husband in the prestigious Brazilian diplomatic corps, allowed Lispector to flourish as a writer, despite the obstacles she faced as a woman attempting to write and publish in a male-dominated culture that was skeptical of this foreign woman and her strange name. As one Brazilian critic noted of her work: “There are no chandeliers in Brazil.”

The Chandelier centers around its heroine, Virginia, growing up in the nondescript, rural “Upper Marsh” in a mansion known as “Quiet Farm” with her brother Daniel, until she is eventually old enough to move to an unnamed city to pursue her studies. While the novel might be generously described as “quiet,” without much of a plot, it instead concentrates on Virginia’s intensive, meandering internal monologues as she tries to understand her place and identity as a woman. While playing one day as a girl, she sees the novel’s eponymous fixture:

But the chandelier! There was the chandelier. The great spider would glow. She would look at it immobile, uneasy, seeming to foresee a terrible life. That icy existence. Once! once in a flash — the chandelier shed chrysanthemums and joy. Another time — while she was running through the parlor — it was a chaste seed. The chandelier. She skipped off without looking back.

For nearly 300 pages, this is the only reference that Lispector gives to the curious and inscrutable title — the chandelier of Quiet Farm that Virginia looks into only to see a doomed future. It’s description and resonance for Virginia, as she’s figuring out what it means to be a woman and have a body in Brazil and the world, is striking: a glowing spider, at once a seductive flower and a hard seed. From the start, Virginia is perplexed by all the irreconcilable demands of society on a woman’s body. After returning home from the city for her grandmother’s funeral, Virginia realizes, near the end of the novel, that the chandelier had vanished from Quiet Farm:

She was looking through the window and in the lowered and dark glass was seeing mixed with the reflection of the seat and the people the chandelier. She smiled contrite and timid. The featherless chandelier. Like a great and quavering cup of water.”

Virginia’s memory of the chandelier as an adult is as strange and ambiguous as the rest of the moments in the novel, deeply introspective and without a clear meaning, but the energy and spiritual wonder of her descriptions make the cryptic writing all the more resonant and spiritually urgent for both her character and her reader.

Even from a young age, Virginia is resolutely fixated on her body, its perceived awkwardness, and the bodies of others, which only intensifies as she grows older. Like the chandelier, she feels at times glowing with beauty but also as awkward and horrid as a spider. In a world before Photoshop and Instagram models and the concept of body dysmorphia, Virginia’s perpetual anxiety about the shape of her body, how she fits into her space, is nearly prescient, like when she is looking out her bedroom window at Quiet Farm: “She would grow more alone, watching the rain. She felt purplish and cold inside, her body a little bird was slowly asphyxiated.” Or later, when an adult Virginia attends a dinner party in the city and obsesses over the beauty of one of the other women:

What was making [Maria Clara] difficult was the crystalline part of her body: her eyes, her saliva, her hair, her teeth and dry nails that were sparkling and isolated

. . .Maria Clara’s pink camelhair dress was reminding her of a motionless river and the motionless leaves of engravings. With a movement of her leg, with the breathing of her breast the river would move, the leaves flutter. How clean and brushed she was.

All these beautiful women, fawning over Virginia’s lover, Vicente, make Virginia begin to feel not just jealous, but murderously inadequate, until “there was no point pretending she wasn’t beautiful, she would penetrate your heart like a sweet knife. The thin, confident women were chatting — they seemed easy for the men and hard for the women; and why didn’t they have kids? my God, how disconcerting that was.”

Throughout all this, Virginia struggles under the brutish and commanding nature and memory of her patriarchal father and the manipulative Daniel. Daniel’s psychological torment only furthers Virginia’s introspection and crises of self-doubt, her low self esteem and her paralysis preventing any change in her life. Once, while playing as children, Daniel commands Virginia: “Virginia, everyday when you see milk and coffee you like milk and coffee. When you see Papa you respect Papa. When you scrape your leg you feel pain in your leg, do you get what I’m saying? You are common and stupid. . . you don’t think, as the saying goes, deeply.” It is no surprise, then, when Virginia struggles to connect with the men that she meets in the city.

Despite being lovers, she is hardly able to strike up a conversation with Vicente. Virginia befriends her apartment’s married doorman, Miguel, and they share platonic but intensely romantic evenings drinking coffee and reading the Bible to each other — a sort of recompense for their quasi-immoral behavior. Eventually, the guilt is too much for Miguel and he tells his wife, and he and Virginia end their rendezvouses on sour terms. The repercussions of a stilted and repressed youth ripple throughout the psychodrama of Virginia’s life — Lispector herself did psychoanalysis for many years and was familiar with the trauma a wrecked childhood could have on a person: her mother, who was raped while fleeing the Ukraine, contracted syphilis and suffered paralysis before dying in Brazil when Lispector was just a girl. Her father struggled to provide for her family, working as a peddler, and died of an untreated illness before her first book was published, leaving Lispector orphaned at twenty. As Vicente notes on seeing Virginia for the first time: “she looked like a child withered, withered between the pages of a thick book like a flower.”

Lispector herself did psychoanalysis for many years and was familiar with the trauma a wrecked childhood could have on a person.

In his biography of Lispector, Why This World, Benjamin Moser writes “Clarice Lispector has been compared less often to other writers than to mystics and saints.” In reading The Chandelier, one finds an odd, mystical sort of clairvoyance in its pages — after pages and pages of a spiraling, circuitous, and rambling thoughts, the narrative will come up for air with a remarkable suddenness. A line, a passage will rise to the surface and ring brutally true or poignantly absurd. Near the end of the novel, Virginia reflects on the discomfort of even her own name:

Boys and girls would have to change their names so much when they grew up. . . after losing that perfect, skinny figure, as small and delicate as the mechanism of a watch, after losing transparency and gaining a color, she could be called. . . any other name except Virginia, of such fresh and somber antiquity.

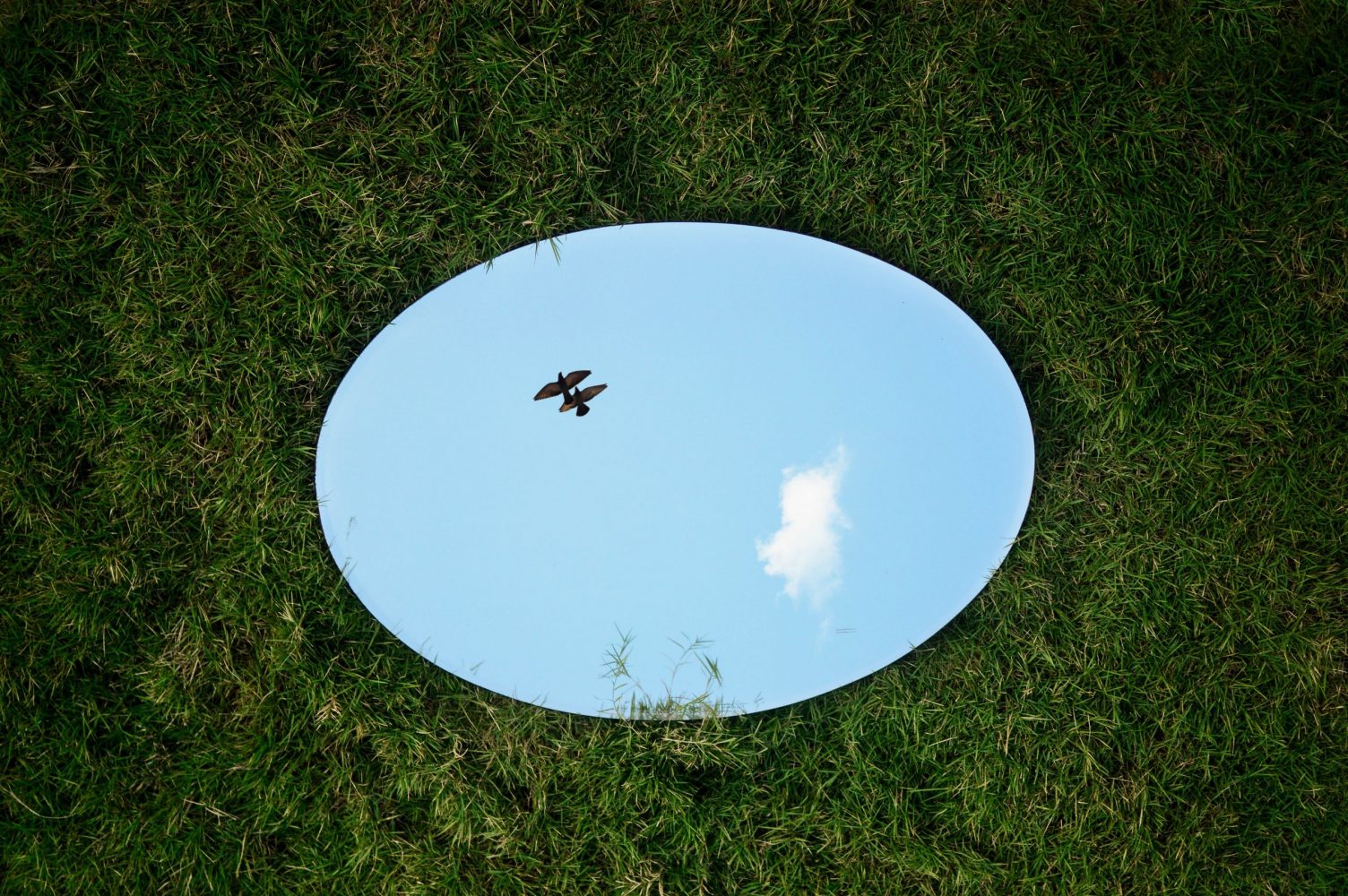

The Chandelier, too, becomes a mutable thing, not just for Lispector’s heroine, but for any who look within its pages and sees what strange thing is shining out.