Lit Mags

The Rise and Fall of the Luxury Baby Farm

“Ourselves, A Little Better” by Mai Nardone, recommended by Territory

AN INTRODUCTION BY THOMAS MIRA Y LOPEZ

When Mai Nardone first sent me this story, he referred to it as “a thought experiment.” But then he added “I’m not sure what it is really.” He’s right, delightfully so.

This story requires you to do something different with the way you digest knowledge.

“Ourselves, A Little Better” is a work of fiction unlike many others I’ve read before, unlike the other work I’ve read of Nardone’s as well. It’s part reportage, part character study (see: Dr. Sims’ half-and-half creamers), maybe even part-Gothic, as if Edgar Allan Poe were asked to translate a peer-reviewed article for The New Yorker. It’s told, against all expectation, in the first person. Blink and you’ll miss it. The voice, sly in its intrusions, remains anonymous, in the way that the first-person in The Plague or Pnin remains an enigma for much of the narratives.

But the ways in which “Ourselves, A Little Better” deviates from conventions make the story what it is. The narrator documents the science of genetic modification with a fastidiousness that both obscures and reveals the consequences of such an ethics. Like one of Dr. Sims’ experiments, the story bides its time until “forking unexpectedly” and pinning us down upon a matter-of-fact image of horror. The story could be satire, except there seems no opportunity for instruction. It takes place in a future too far away to remember the lessons of the past, yet not far enough to avoid their repetition.

I would argue that the story challenges, perhaps even undermines, how we as readers interact with content and information. If you are like me, and clicking on internet links feels like a game against time — one in which you justify the tendency by focusing on the accumulation of information and opinion — then this story requires you to do something different with the way you digest knowledge. We learn science that is plausible but not yet possible and while the science presented in the story matters, the human permissiveness that allow these developments to take place matters more. The justifications we indulge in order to make ourselves feel a little better matter most.

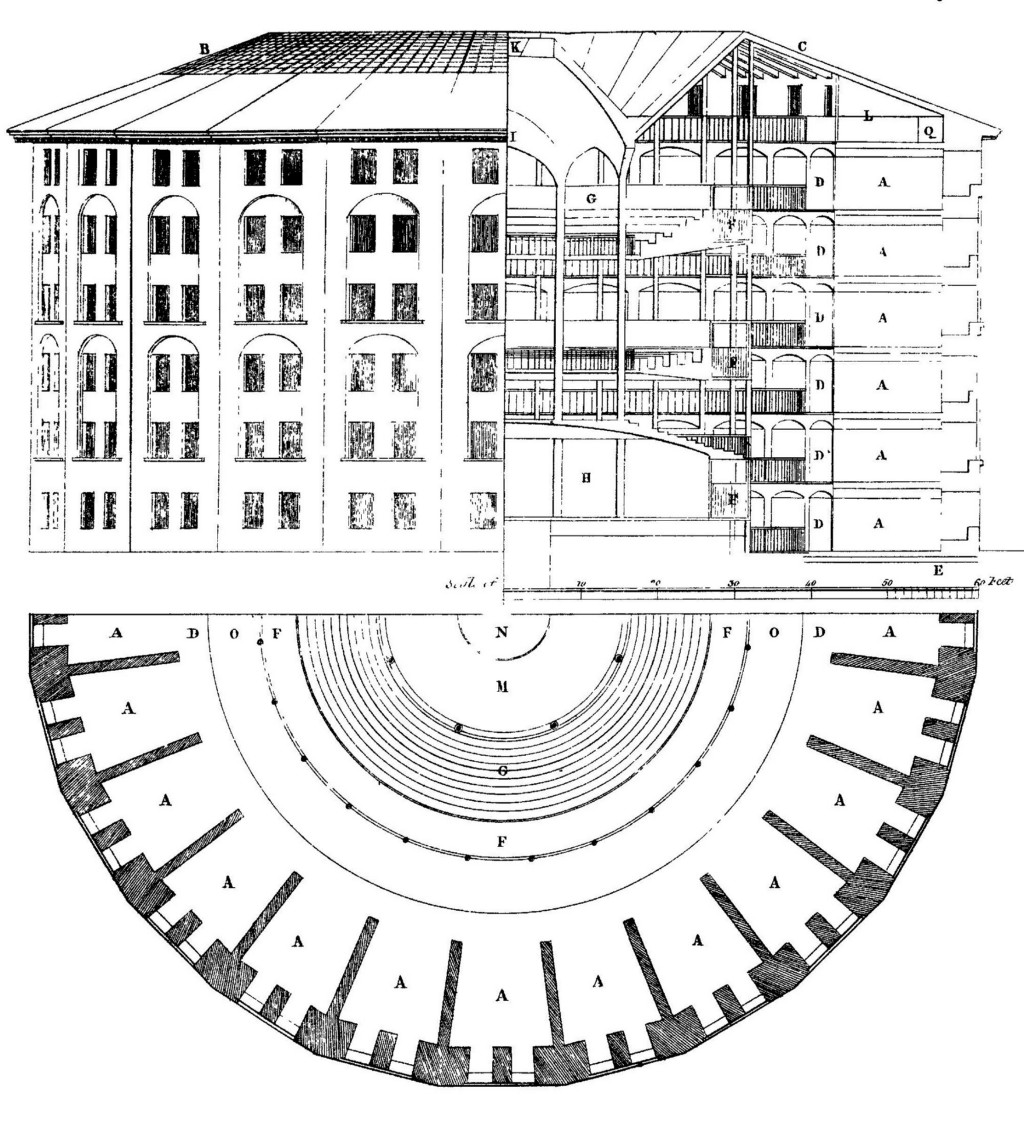

At Territory, each issue we publish has a theme and each piece we publish is based off a map that embodies that theme. Our theme for Nardone’s issue was “Prisons” and Nardone chose to work with a map of the Panopticon. The Panopticon, designed by the 18th century English philosopher Jeremy Bentham, is a circular prison in which all inmates could be observed by a single watchman. It is either a utopian or dystopian structure, perfection or perversion, a mark of utilitarian progress or an overstepping of bounds. In other words, it’s the thought experiment that Nardone found this story to be.

Thomas Mira y Lopez

Territory

The Rise and Fall of the Luxury Baby Farm

Mai Nardone

Share article

“Ourselves, A Little Better”

by Mai Nardone

NEW HOTEL

The opening was timed for the anniversary of the first test tube baby. A facility erected as a milestone: five decades of obstetrical progress. The chosen ground was a frontier of Bangkok, itself a forerunner in the contest for medical tourists. It opened as Newbirth Centre Asia, but for its hospitality-trained staff would be known locally, and later infamously, as New Hotel.

Ourselves, A Little Better (Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading Book 286)

The first commission was from a photogenic Australian couple, Bill and Joyce Boe of New South Wales, of tabloid-famous infertility, of an undefined beige ethnicity. They wanted a boy. Less than a year later, baby Adam was born to specification: 8 lbs., hazel eyes (his mother’s), AB+, and free of Bill’s family’s strain of an enzyme deficiency disease. The headline of The New Century, an Australian newspaper, exalted, “Science Bests Nature”.

UNNATURAL SELECTION

Dial back one decade and two patents, to the year New Hotel’s founder Dr. Susan Sims, then an embryologist at Waindell Medical Institute, pioneered a technique for egg harvesting and maturation.

It was a triumph of will more than science. Sims, Connecticut raised, had been drilled by prep-schools and a childhood fascination with natural selection to understand existence as competition. Like the best Thoroughbreds, she knew only forwards, the grind of track dirt underfoot, the constant gnawing at the bit. She spent her thirties butting her head against the gates that held her back, thwarted in her experiments on oocyte maturation. The object of her obsession she found under the microscope, the prison of her vocation: cell boundaries. She kept a habit of snacking from a bowl of flavored, half and half creamer capsules as she worked. French Vanilla, Hazelnut, Sweet Crème — everyone, said one former lab assistant, “knew what to buy Susan for Christmas.” The popped, crumpled shells littered her desk, giving off the sour stench of obsession. Sims preferred to work alone, and alone she made her discovery.

In vitro maturation (IVM) is the maturing of oocyte in a petri dish (hence, ‘in glass’). At the time, IVM was already on its way to displacing traditional egg harvesting procedures, which required the egg to mature in a woman’s womb before being extracted. IVM made egg donation easier; donors no longer had to endure procedural injections of a hormone cocktail. Dr. Sims’ method also improved egg quality and doubled embryo yield. She produced an unprecedented pregnancy rate: 74%. She didn’t publish the findings or disclose them to the university. Instead, she forfeited her position and, like every great American innovator, took the technology private. A year later Sims’ California-based fertility clinic, the Hatchery, came to be.

Enter here the marketing guru behind the Hatchery’s rise, Sims’ partner Denis Osman, who in a previous incarnation had made his name pushing pregnancy skin care products (breast firming cream, elasticity oil, stretch mark gel). Moms of the AOL era may recall the NewYou campaign, a weekly newsletter detailing postpartum mothers experiencing a ‘rebirth,’ second lives as figure skaters or salsa competitors. By the late 90s one prominent magazine was referring to Osman as “the patron saint of new mothers.” Still, his downfall was swift, the result of boasting, on a late-night show, that he had penned the stories himself. The Hatchery became Osman’s own opportunity at rebirth.

Denis Osman’s talent was understanding that relative ease of egg donation after IVM changed the way donors could be wooed. The Hatchery opened as an all-around fertility provider, but was quickly driven to mainstream attention for its hallowed egg donor database. Osman bought full-page ads in newspapers. A booth pushing donation popped up outside the Harvard Square T Stop, and fliers dotted the third-wave coffee shops of Princeton, NJ. Teams of intern copywriters produced think pieces that were pushed out through content recommendation engines. They directed chatter down the why-not route: the money was good, the process was (almost) painless, the eggs would have been flushed, anyway. An early employee of the Hatchery recalls a training session in which she was told to identify target donors as “Ivy League and Out Of Your League.”

The Hatchery went an extra length by providing each donor with complimentary cryostorage of a dozen of her eggs, which were vitrified (‘turned-to-glass’ rather than ‘frozen’). To reinforce this point, in the cavernous lobby of the clinic hung an impressionistic oil painting [1], an artist’s idea of what vitrified human eggs, collected in straws and stored in a dark swirl of liquid nitrogen, might look like: a string of rhinestones, a belt of stars. A hedge against the future — what if? The result of Osman’s campaign? Donors signed on in droves. Soon, the Hatchery had its pick of the country’s ‘finest’. And once the Hatchery had its pick, so did its clients.

[1] Now displayed in the Human Odyssey room at the California Academy of Sciences.

A survey of donor profiles, recovered from a cloud storage facility where the backup database was held, gives us an idea of what a perusing client might have seen. Each profile included a banner, often a collage, but sometimes a single image (a still lake, a rising sun, Machu Picchu). The pictures were themselves a timeline, beginning with baby-with-attitude through cap-and-gown. The average age of donors was twenty-five. Dimples were advertised. Ethnicity, hair type, body type, body weight, body hair, height, SAT score, eye color. Do you: sing in the shower; have gay or lesbian friends; like your handwriting; believe in life on other planets. Donors touted “strong leadership abilities” and “team player.” The language was always effusive. Ancestry.com provided the genealogy, complete with known monogenetic diseases. Everyone had gay friends. Less than one percent of donors identified as gay. Questions most often left blank: Corrective lenses? Multiple sex partners? College GPA? One early donor ended her personal statement with, “I love animals, human bodies, and working out. I love healthy meals. I use my artistic abilities to draw anatomies.”

Two years after opening, the Hatchery had already captured a third of the domestic reproductive technology market, prompting the Federal Trade Commission to open an antitrust investigation into the company’s practices. The Hatchery App topped the Lifestyle category of the App Store (for its app, Osman had hired the product team behind that decade’s most popular dating application). Eggs stored in cryogenic capsules were being shipped worldwide. The period also saw a rise in offspring t-shirt slogans: Rappaccini’s Daughter, Son of Krypton etc. The New York Times ran an Op-Ed piece titled What Do We Do With All These Eggs? an echo of investors’ cautiousness about the egg-donor boom. The public supposed a natural limit to the growth. Was infertility on the rise? It was not.

THE NEW GALTONIANS

For outsiders, the chief difficulty of extrapolating the future of the Hatchery was the seclusion of its founder. It wasn’t that the Hatchery was a particularly secretive institution — to garner client trust in what was a relatively new field, the staff was transparent, the legal team explicit, the doctors accessible. But each subsequent circle of workers obscured the founder, a cumulative effect, as of translucent sheets overlaid. Sims was known to work in isolation, in her laboratory in the center of the circular structure. She had her own entrance that opened onto the carpark. One employee worked there three years and only saw Sims twice. “We didn’t know if she was in or out. We had a running bet, a pot you contributed a dollar to each morning.”

This isn’t to say Sims neglected her duties as boss. She was meticulous, collecting all the client reports, reading each donor profile. Handwritten notes of commendation were shuttled from her lab to the employees. One recovered note reads, “Tracy, superb work with the Mendez family. You really surprised me this time.” It was an eerie juxtaposition of platitudes and detachment for some, but many were spurred on by the Sims’ gaze, as if aware of a coach’s presence on the sideline. One employee described the environment of the Hatchery as a modern-day Panopticon: was Sims watching now? Sims was present in the soothing minimalism of the lobby and the multi-flavored creamers available in the break room.

Other scholars have argued that there were clues in Sims’ interests, and in the few interviews given by Osman, but such reports are overblown and entirely retrospective. When Sims eventually went on trial, for example, the tabloids went into a frenzy, reading into the Sims’ court-presented possessions the doctor’s peculiarities. They wanted a Henry Jekyll, a Victor Frankenstein. Instead, they found a shy, messy woman. The most portentous of the items turned out to be the bedside reading:

Leach, Gerald. The Biocrats: Implications of Medical Progress

Hornblum, Allen M. Acres of Skin: Human Experiments at Holmesburg Prison

Galton, Francis. Hereditary Genius

Galton, Francis. Kantsaywhere

The last entry especially captured the public’s imagination. Kantsaywhere, written by Charles Darwin’s half-cousin Francis Galton in the early 20th century, is a novel describing a utopian, eugenic society. Sims in college had founded the New Galtonian Society, an unsuccessful attempt to resurrect Galton’s ideas about the inheritability of intelligence in the context of modern genetic determinism. The club only held one meeting, which Sims attended alone, surrounded by chants of a student protest staged outside the classroom.

So how does an idea that a couple decades previous had been spurned by an entire student body come to the mainstream? Michelle Huang, bioethicist and historian, notes in her book Manufactured Evolution that there was a necessary confluence of scientific advancement and “unregulated thinking” to augur the rise of Newbirth and the making of New Hotel.

Huang points the sequence of thinking that was rekindled under the Human Genome Project and saw the proliferation of ‘Understand Your DNA’ services. The mapping of the human genome demystified that final frontier. And although the new preeminence of genetic determinism spawned a number of protests about scientific tyranny and even a hit documentary from The National Geographic titled Cells: Imprisoned by the Genome, the movement lacked the conviction of previous decades.

In medical circles at the time, restrictions to gene therapy were being debated. Recombinant DNA, the technology for genomic editing, had come of age. It was possible to edit germ-line DNA (eggs and sperm) and therefore scientifically feasible to genetically augment (or diminish?) future generations of humans.

At the same time, Huang argues, the world was undergoing a separation of family and kinship. The modern family was an economic unit, a household — consanguinity had lost consequence. The previous year had seen the abolition of the last monarchy (the biggest champion, as it were, of the bloodline). A new era in American statecraft reintroduced pro-democracy regime change on a scale reminiscent of the Cold War. The Arab Spring swept North Africa, and covert CIA operations led to the fall of other dynastic autocracies (see the example of North Korea). Even the family-industrial model favored among the ‘Asian Tiger’ economies had given way to public companies. This was true especially in South Korea, famous for ascension through the avenues of chaebols (Samsung, Hyundai), those paragons of the family conglomerate. Thus, it mattered less in the modern era whether children resembled parents. What was important was improvement, each generation producing a better specimen than the last. Birth became not about reproducing genetic features, but improving upon the old.

Perhaps when we abandoned family, we also lost sight of legacy, and therefore history. The last of the Auschwitz-Birkenau survivors had passed away, and despite the best efforts of schools, new wars were layered over old wars. 20th century eugenics was too far back to provide its cautionary tale. That history had fossilized; it was the wreckage of an earlier civilization.

Huang’s storyline, however, treats history’s course as that of a river: its ocean destination inevitable, and coaxed by the earth’s topography. And yet only a visionary, like Susan Sims, could have charted that route in the present. And there were signs of her unique vision. From its inception, the Hatchery hadn’t been registered under its own name, but that of a parent company called Newbirth.

MAPMAKING

One of the documents to survive the Hatchery’s paper purge, which preceded the court hearings, is the handwritten notes of one doctor. Under the heading Corrections, the doctor has scrawled the following: “Type 1 diabetes, myopia, father’s height five inches below the national average, poor visual-spatial intelligence.”

Imagine now that you believe in the correlation (and it’s been argued there is one, especially in men) between height and success. You’ve lived with the daily inconveniences of myopia, the shadow of diabetes, a lifelong difficulty interpreting maps. A fertility provider promises to manufacture the desired result. The Hatchery was already in the business of gene therapy. Preemptive genetic screening was a given, and the usual suspects — sickle-cell, Tay-Sachs, hemophilia — were routed. Sims simply needed to expand the existing menu and up the price. She asked Osman if he could sell it. He said he could.

NEWBIRTH: OURSELVES, A LITTLE BETTER

The phrase was borrowed from James Watson, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA. His response to questions on the potential of genetic engineering was, “Why not make ourselves a little better.”

Osman also studied DuPont Pioneer’s successful branding of genetically ‘edited’ crops, a follow-up to the poorly marketed GMOs of the previous decades. The language of education was employed: head start, trajectory, success. Osman molded the message to suit focus groups of various demographics. The message was always positive; it emphasized augmentation. Through the Newbirth campaign, Osman hoped to gently usher the world into a new age of genetic tinkering.

Sims meanwhile had utilized her egg database to map polygenetic traits that could be marketed to intended parents. Polygenetic diseases had long plagued the scientific community. How to pinpoint the responsible genes, given how many different genes could influence, say, heart disease. Such diseases were not as easily isolated and snuffed out as monogenetic ones, like sickle-cell anemia. Germ-line augmentation was only as good as the traits that could be isolated. Many in the scientific community moved on to epigenetics, and the naysayers trailed those advances for a time.

Sims, however, had delved into the race to map master-regulator genes (a race led, incidentally, by Sims’ former employer, the Waindell Institute). A master-regulator gene is a gene thought to determine the pathway for cell fates. It’s a switch that creates a cascading effect; an initial flash in the bolt that arcs through the human genome, forking unexpectedly, activated or muted by environment, by chance. Sims realized that she only needed to isolate the such genes for the select traits she wanted to sell. Hers was a nimble and small operation. She already had the largest collection of human eggs and corresponding genealogy ever amassed. Also, America’s embryonic stem cell research was sluggish in returning from years of suppression under the Bush Jr. administration. Within a year, she had already isolated three master-regulators, discoveries that only surfaced for the scrutiny of the hovering NIH, Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee, and FDA when Denis Osman filed patents for the genes’ locations.

Sims wasn’t doling out certainties, of course, but propensities. Switch on a gene and increase the likelihood for logical-mathematical intelligence, for verbal-linguistic intelligence, and even, perhaps, for kindness. How she charted the cascade set off by the master-regulator gene was described by one geneticist as triangulation. Sims fixed one trait’s position using its relationship to two known traits, and once oriented, mapped down, pausing at each level to find her bearings. Once she had covered the master-regulators for various intelligences according to Howard Gardner’s theory of intelligence, she devoted herself to other favorites from the questionnaires: leadership ability, body type, dimples.

MEANWHILE…

Osman, in filing the patents, had in mind success on the scale of Genentech’s patent of recombinant insulin in the 80s. His ambitions were quickly stymied by the courts.

Meanwhile, The Economist magazine ran a special report on surrogacy, highlighting China after the lifting of its one-child policy. Picture this: Chinese families wanting for first sons, more sons, but the mothers beyond childbearing age. There followed increased demand for women who could carry a fetus to term. That demand, it turned out, was huge. Market forces prevailed. Thailand and India became the world’s surrogacy destinations.

Meanwhile, Sims was vacationing in Thailand. What was she doing there? Scouting. She would find Thailand a hospitable country for Newbirth. It already had an established gestational surrogacy industry. Also, thanks to a recently-completed high-speed rail that began in southern China and stitched together Southeast Asia, Bangkok was the playground of China’s millionaires. Specific records of Sims travels are scant, especially because the attention of geneticists and the media was on the patent case, which that week was settled by the Supreme Court.

What was patentable, it turned out, was Sims’ method. But no matter. On the other side of the world, the foundations were being laid for Newbirth Centre Asia. Its primary market was China, a nation less squeamish about the sort of genetic augmentation Sims would sell. The previous year, genetic modification of the human embryo had been attempted at Sun Yat-Sen University with barely a ripple of dissent. China was a country of over 10 million millionaires. Its Ministry of Culture had spent the last decade pushing money into ‘historical’ blockbusters with the purpose of re-education. They emphasized Confucian principles. And so, when time came for Osman to put together a narrative for the marketing team, he sold two packages. One involved surface changes, what Sims liked to call ‘the shell’, and the other emphasized the Five Constants of Confucianism:

仁 Ren — humaneness

義/义 Yi — righteousness

禮/礼 Li — propriety

智 Zhi — knowledge

信 Xin — integrity

How and whether Sims isolated a ‘righteousness’ master-regulator is unclear. Being a private enterprise, Sims’ research wasn’t open to peer review, and with its Thailand base, it wasn’t under the scrutiny of the FDA.

Build-a-baby, as the process was later called, started at USD 300k. This base package involved “maximization.” The baby’s genome was comprised of the best of each parent, without any additional features. Augmentation (beyond maximization) was 50k-80k per feature, depending on the difficulty in creating a reasonable propensity for that feature.

At the program’s inception, the main obstacle for Newbirth was that the pregnancy rate for in vitro maturation was still 74%. Given the intricacies of gene editing and the wait to see whether the fertilized embryo would take, Sims realized that it was inefficient to implant the embryo in the intended mother. Instead, she used surrogates. She implanted identical embryos into four women (sometimes as many as eight) at a time. If more than one fertilized egg was successful, they aborted the remainder, a cold and clinical and demonstrably effective strategy.

For its first trial (a batch?) Newbirth Centre Asia received over ten thousand applications from all over the world. Osman chose the Boes as the poster parents, citing their “empathetic features”.

CHAMBERS

The New Hotel is today a museum, a display of hubris, or ambition. Try the guided tour. One guide suggested to me that the structure was built to resemble a cell: solid outer boundary, the nucleus of the main office in the center of a glassy atrium. On a later visit, I was told the structure most closely resembles Jeremy Bentham’s fabled Panopticon, a prison design. The upper chambers, they’ll tell you, are where the surrogate mothers were imprisoned during their pregnancies. They’ll use that word: imprison. You’ll be invited to step inside a room.

Personally, I see in the structure a Russian doll effect: hollows within hollows. The facility, a round chamber, and within it chambers, and the mothers, round, fulfilling roles as chambers. And when you’ve arrived at the smallest chamber, a thing growing.

A year after New Hotel opens, Sudhidaa Chaiprasit, an undercover journalist, enrolls herself in a new cohort of surrogate mothers. What follows are the headlines we know: GENETICIST GROWS POST-HUMANS IN PRISONERS. We learn of a surrogate’s self-induced miscarriage, of a suicide, of infanticide. New Hotel is shut down.

Sims is later charged by the International Criminal Court of violating the Nuremberg Standards. Osman and the lab technicians testify to believing that the implanted embryos belonged to clients. Many were actually Sims’ experiments. She needed chambers; she hid her experiments in the children born to clients.

The following was taken from Sims’ court statement:

“I tried to free us from genetic determinism. From our evolution, our genes, which will fail us. You look at me and see the worst of humankind. I looked through the glass and saw in my work a future for our kind.”

In her experiments to perfect the human race, Sims held the embryos against a standard that could be traced back to the client questionnaires of the Hatchery. She wanted to create the ideal embryo, and by planting it her army of surrogates, begin the work of propagating a generation of post-humans. Ourselves, a little better.

On the eve of the trial’s verdict, Susan Sims kills herself with an injection of phenol to the heart. She is 49.

Despite the media barrage, there’s much that was kept secret by the Thai police. We don’t know, for example, how many children were born to Newbirth in that first year. A conservative estimate puts the number at two hundred. It’s suspected that the CIA has been working to track down the children for genetic testing.

And what of the promised qualities? Was Sims successful in her attempt to imbue these children of science with the Five Constants? The many intelligences of Howard Gardner’s theory? With kindness? It’s not known whether she managed to perfect the embryo according to her designs. However, Sims, who never married, kept in her home a vat of liquid nitrogen, a chamber, in which she stored a straw of her own embryos, vitrified and glimmering, already modified, already fertilized, one woman’s ante in a game for the future — what if?