Reading Lists

The Rise of Dystopian Fiction: From Soviet Dissidents to 70’s Paranoia to Murakami

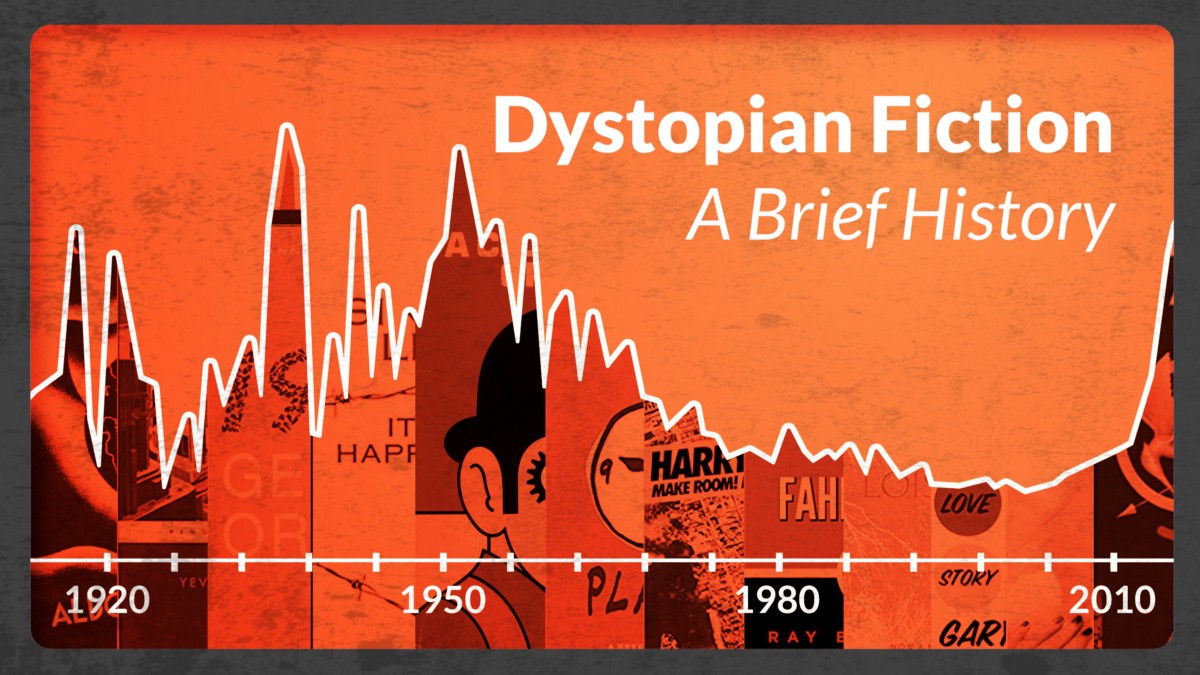

Charting the wild progress of literature’s genre-of-the-moment

George Orwell is back in vogue these days — a far cry from 2014, when The Guardian was debating whether or not 1984 was good bad or bad good fiction. In January this year, 1984 shot up the bestseller charts, and the trail doesn’t just go cold there. Soon joining it at the top were 1984’s old dystopian buddies, Brave New World and It Can’t Happen Here; in the meantime, sales of The Handmaid’s Tale were up 30 percent in 2016.

We are re-reading these past giants of the genre, even though we’re used to the idea of dystopia in our pop culture by now. (Credit where credit’s due: The Hunger Games was something of a big factor.) Yet the dystopian novel — as we know it, in its full totalitarian glory — is itself a relatively new phenomenon. Before 1900, only the British satirist Jonathan Swift wrote books that could, with one eye squinted, be called dystopian. So when did dystopias and dystopian themes start taking off in modern fiction? And is there a pattern to their rise and fall throughout the past?

Origins

First, there was the concept of utopia, the yin to dystopia’s yang. The former sprung from the mind of Sir Thomas More, who wrote Utopia in 1516. Ironically, More possessed serious reservations about the existence of utopias. (The word itself could be a pun, derived from the Greek word u-topos (“no place”) and also eu-topos (“good place”). Such a good place, More seemed to reason, was not anything we knew, and so it must not exist.)

If a utopia is a place that’s too good to exist, a dystopia is a place that we certainly don’t want to exist.

Today, we can define dystopia as “an imagined place or state in which everything is unpleasant or bad, typically a totalitarian or environmentally degraded one” (OED, 2017). The first public usage goes all the way back to John Stuart Mill in 1868. In a speech to the House of Commons, Mill said, “It is, perhaps, too complimentary to call them Utopians, they ought rather to be called dys-topians, or caco-topians” (‘cacotopia’ was relegated to the Wastepaper Basket of History). But it wasn’t until about 50 years afterward, when authors made the word their own, that the idea of dystopia began to actually take root in the public consciousness.

1920s & 30s: Defining The Genre

Perhaps it makes sense that the modern dystopian novel emerged at the turn of the 20th century. It was a time of political unrest and global anxiety, with two world wars awaiting in the near future. Jack London’s 1908 novel Iron Heel was said to be a remarkable prophecy of the impending international tensions that would give way to World War I. Yet we don’t see dystopian fiction becoming a more defined genre until the publication of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s slender We in 1921.

Before We, fiction about an “ideal” society (with the exception of H.G. Wells and London) tended to end utopian. After We, the genre took a grim downturn (or upturn, depending on which way you’re squinting). We set up many of the tropes that would come to dominate dystopian fiction. These included troubled, unresolved endings (very fun!) and a totalitarian government gone mad.

Also importantly, Zamyatin’s book greatly influenced two fictional works that tower over the rest of the genre to this day: Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s 1939 Brave New World. Both were written in the shadow of a world war. Both predicted an even darker future. Admittedly, the worlds within these two dystopian novels differ vastly, and the influences that Orwell and Huxley feared were not the same. According to critic Neil Postman:

“What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egotism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumble puppy.

In short, Orwell feared that what we fear will ruin us. Huxley feared that our desire will ruin us.”

But the stage for the genre was set, in spite of any differences. In this early crop of dystopian fiction, we can see the themes over which future novels would continue to obsess: political capital, the meaning of free will, and, perhaps most significantly, fear of the state and the unchecked power of government.

Prominent Dystopian Fiction from the Era

In Huxley’s colossally chilling vision, people come to adore the very authorities that undo their capacities for thought. Half of the Big 2.

Whereas Huxley’s dystopia is based upon affluence and pleasure, Orwell’s 1984 is just gray totalitarianism: a towering cross-examination of government surveillance, information, and the meaning of freedom. Gave rise to the concept of Big Brother. Half of the Big 2.

An often unacknowledged father of modern-day dystopian novels, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We predated both Orwell and Huxley, and inspired Brave New World.

A semi-satirical novel that experienced renewed popularity after 2016. It Can’t Happen Here was written in 1935 and predicted a fascist America under the control of a dictator.

1950s and 60s: War And Tech

OK, we’re out of the woods of World War II, you say. Time to breathe a sigh of relief! Surely, post-war optimism means that authors are going to start cheering up, right?

Sorry. This chart from Goodreads says, nope!

Political commentary shouldered many of the dystopian themes that emerged from the end of the war. And World War II fueled the prospect of World War III and apocalypses. (See: Kurt Vonnegut’s classic Player Piano in 1952 and Philip K. Dick’s 1964 The Penultimate Truth.) We do differentiate between apocalyptic fiction and dystopian fiction — but there’s always a fair bit of crossover when crumbling societies and their governments are involved.

Incidentally, it was during this time that authors’ growing suspicion of technology bubbled to the surface. Some major technological advances during this time included:

- the inception of the Turing test (a test for intelligence in computers)

- the creation of Sputnik I

- the invention of the first personal computer

As a result, dystopian novels began to cross paths more regularly with science fiction worldbuilding, such as in Dick’s 1968 novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

After witnessing war, authors grew particularly concerned with totalitarian governments’ ability to regulate the arts. One of the most popular examples continues to be Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, which breathes into awfully vivid life the possibility of a future in which books are burned. (Today, Fahrenheit 451 is banned in many schools in the United States, and so one cannot say that real life does not possess a solid sense of irony.)

Prominent Dystopian Fiction from the Era

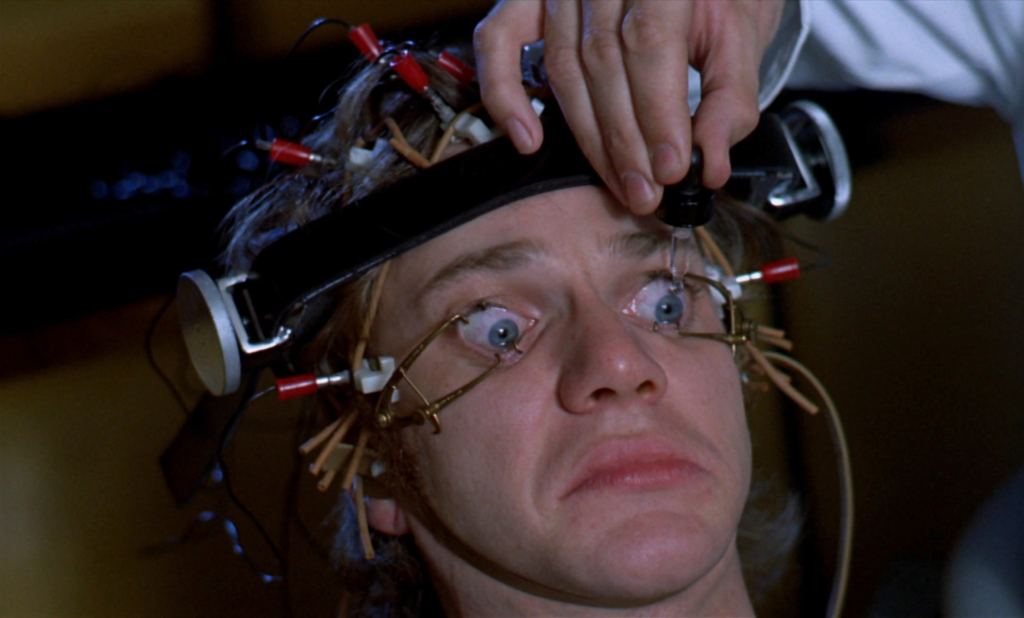

The brainwash of an ultraviolent youth in A Clockwork Orange’s dystopian but complacent society allows author Anthony Burgess to pose this question: “Is it better for a man to have chosen evil than to have good imposed upon him?”

Internet thinkpieces about machines presiding over the future are nowhere near as grim as Vonnegut’s Player Piano, set in a class-divided society after World War III.

A classic novel of overpopulation. In a crime-ravaged New York City, food is scarce and the government is rationing portions of a mysterious substance they call “Soylent Green.”

You wonder: why the title, Fahrenheit 451? It’s the temperature at which the paper of books catches fire. In Ray Bradbury’s world, all books are banned — and burned.

In which a man who increasingly wonders about the difference between people and androids he must kill. Also the inspiration behind 1982’s Blade Runner.

1970s-1990s: Corporations and Poisoned Bodies

While the volume of dystopian fiction declined for a period entering the 1970s, the variance within the genre broadened. If the genre reflects our fears back to us, then in the 1970s we see the public moving past a perpetual fear of war to explore new meadows. Environmental crises dominated the conversation (the Clean Air Act was only passed in 1980) while the onslaught of advertising, misgivings over the body, and economic stagnation ushered in a new era of cynicism.

It was a catalyst for quite a few dystopian classics that took the genre in brilliant new directions.

The Handmaid’s Tale, a book in which women’s bodies are nothing more than reproductive machines, shook the world when it was published in 1985.

Cyperpunk was born out of William Gibson’s 1984 Neuromancer.

Private corporations became a wellspring of repression and public enemy #1 alongside totalitarian governments in many dystopian novels, such as Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash.

And meanwhile, black satire became all the more pronounced in the genre, as José Saramago showed in the Blindness and its sequel Seeing, which both use an omniscient narrator to great effect.

Perhaps most notably, in 1994, Lois Lowry quietly published The Giver. A slender book about a community in the future that doesn’t feel pain anymore, The Giver was a dystopian novel for young adults before the breed was cool. It built upon past traditions of adult dystopian fiction while managing to popularize the genre among young adult readers. This would be significant because of what would occur in the next decade or so…

Prominent Dystopian Fiction from the Era

“A world without color — fantastic!” said no-one ever. Yet people embrace this society within The Giver, which asks what a world with Sameness really is: a dystopia in sheep’s skin.

About a robot’s death wish in a world where people don’t possess the ability — and, worse, the desire — to read.

Saramago uses a third-person omniscient narrator and an ever more ominous tone to create this chilling and ultimately bewildering work about a society suddenly afflicted by blindness.

The dystopian world found in this romping science fiction novel was one of the first to introduce cyberpunk to society, capturing first-time novelist William Gibson the Hugo, the Nebula, and the Philip K. Dick Award in 1984.

A vision of a dystopia steeped in gender discrimination, The Handmaid’s Tale was giving folks the shivers decades before it became a popular television show on Hulu.

The Turn Of The Millennium: Youth Betrayed

Today, dystopian fiction is predominantly associated with the young adult genre. Young adult dystopian series — Maze Runner, Divergent, Ready Player One, among countless more — dominate the shelves, bleeding into Hollywood. The Divergent films alone grossed over $700 million in box office receipts worldwide.

How did we reach this point? In big part, it’s due to The Hunger Games, as the trend that The Giver began exploded in popularity among young adults with the publication of Suzanne Collins’ series. In dystopian fiction, young adult readers can find a tangle of themes to identify with: themes of self-discovery, of one young person pitted against the whole terrible world. Overall, the rise in dystopian novels since 2000 is said to be a symptom of the pooling anxieties that followed 9/11 and other troubling geopolitical events.

But The Hunger Games still managed to change many aspects of the game. In an essay, the AV Club noted:

The Giver comes from what seems to be a lost tradition in dystopian storytelling. It used to be okay for genetics to eventually yield an individual who wants to break free from societal homogeny, and choose to escape that oppression to a safer community. Now, merely escaping isn’t enough — dystopian-thriller protagonists must learn brutally militaristic tactics and enact violence that brings tyranny crumbling down in increasingly bloody action sequences.

And so in today’s crop of dystopian fiction, the stakes are bigger than ever. Continuing in a proud tradition, they carry on vindicating the definition of a dystopia: a worst possible world. But what each of them (sometimes) offers is a brief, shining belief that such a world can be fixed. And now, the resurgence of sales for books such as 1984 and Brave New World shows that a vast contingent of us continue to turn towards the genre for comfort, or answers.

Prominent Dystopian Fiction from the Era:

A part of the trilogy that ends with Mockingjay, Hunger Games needs no introduction anymore. Except this: may the odds be with you when you read it.

Like MMORPGs? You perhaps won’t be such a fan of them after you read Ready Player One, which won the Alex Award from the American Library Association and the 2012 Prometheus Award.

(Un)coincidentally, 1Q84 is only one number removed from George Orwell’s 1984. Once called the dystopian novel to end all dystopian novels, this winding epic is a feat of brilliant imagination that only Murakami could’ve conjured.

In the background of a burgeoning romance between a Korean-American and a Russian, America teeters on the brink of economic collapse and consumerism threatens to overwhelm all.

Who says you’re ugly? This book does. Uglies turns a very dystopian eye upon plastic surgery: in this future, when you turn 16, you get an operation to turn “pretty.”