Lit Mags

The Same Ghosts Haunt All Families

Emily Gould recommends “Les Mis” by Kim O’Neil

AN INTRODUCTION BY EMILY GOULD

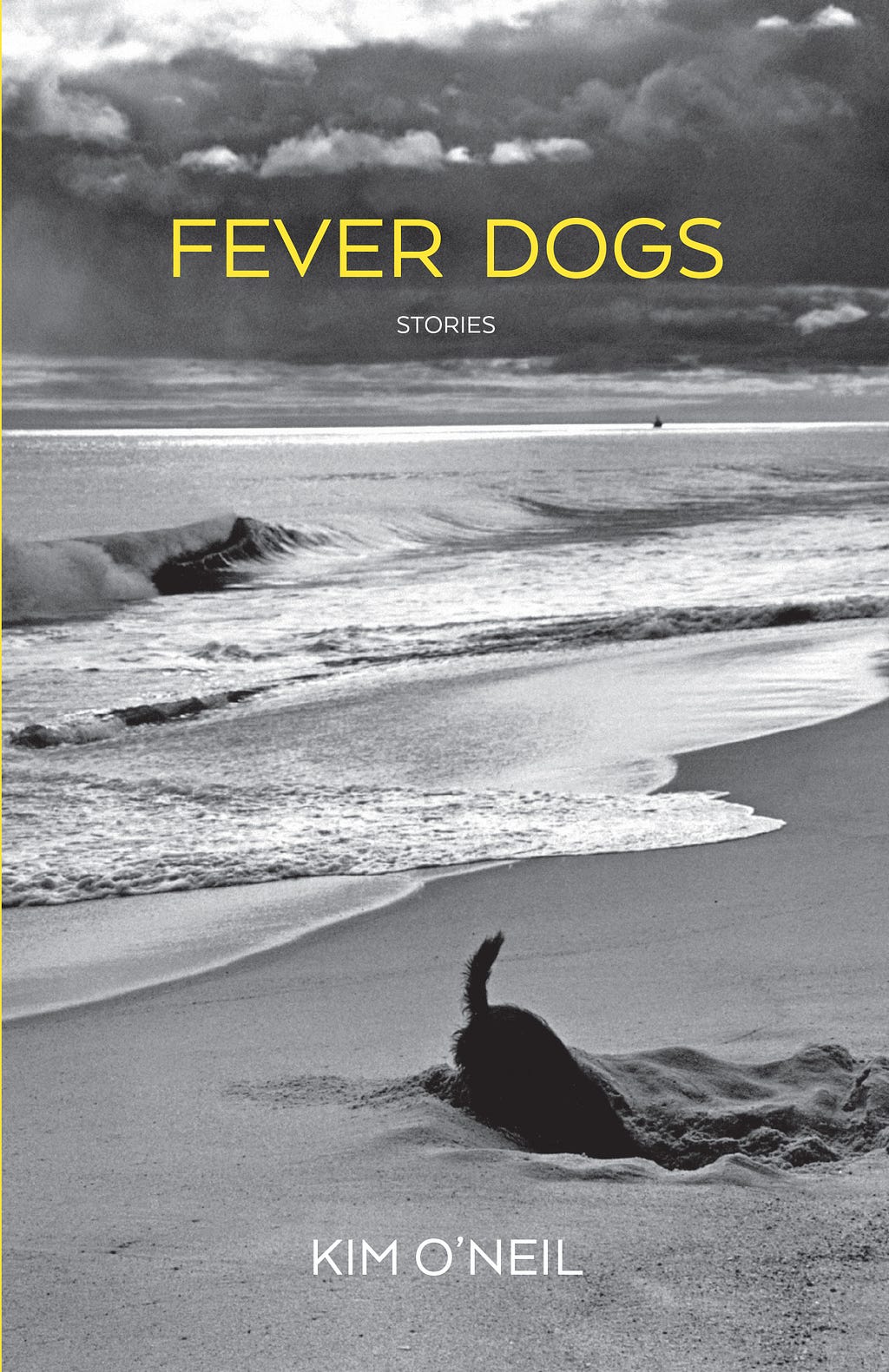

In “Les Mis,” from the new collection, Fever Dogs, Kim O’Neil sends the reader traveling brusquely but thoroughly through time. With her signature rhythmic, flowing sentences, which skirt the line between poetry and prose, she situates us first in the backseat of a car, eating sugary snacks — “an anxious lot of sugar” — as we speed toward Woonsocket to visit “a committee of adults colluding to please you, for reasons that preceded you and were certainly not you.”

All of this and more is contained in just a scant few pages that the reader swallows in a gulp, then digests more slowly, haunted, changed and craving more.

The oddest, most absent, and most important of these adults turns out to be Gramp, near-catatonic in his La-Z-Boy knockoff. Soon the reader is invited to bear witness to the horrors of Gramp’s childhood and his near-death experience rum-running during Prohibition. All of this and more is contained in just a scant few pages that the reader swallows in a gulp, then digests more slowly, haunted, changed and craving more.

The idea that animates Fever Dogs — that the past is not really past and is always with us, etc., — is a familiar one, but O’Neil’s way of dealing with it makes it new again. By telling the story of a family in endlessly recursive vignettes, she makes the stakes of both the present day stories and the historical ones personal and familiar: it becomes clear that the same kinds of ghosts haunt all families. Universal and deeply specific, strange and familiar, Fever Dogs is the rare kind of collection that has the sustained intensity and connectedness of the best novels. And with it, Kim O’Neil announces herself as a writer of near-supernatural power.

Emily Gould

Co-Founder, Emily Books

Author of Friendship

The Same Ghosts Haunt All Families

Kim O’Neill

Share article

“Les Mis”

by Kim O’Neil

For the Sunday ride to Nana D.’s and Aunt Esther’s Jane brought an anxious lot of sugar. The interstate to Woonsocket took one hour. To Jean and Ruth, Jane passed back Tastykakes or Devil Dogs or Yodels or Yoohoos or Ding Dongs or Dum Dums or powder puff doughnuts. The girls accepted these stipends without appetite. Everything with a soft white surprise in the center.

Or else foods that you could make things out of. Licorice ropes an armspan long and filament thin that the girls knotted into chain-gang anklets.

Les Mis (Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading Book 280)

What Jean and Ruth liked best were the turnips. Jane stopped at Sunnyhurst Farm just past the state border. The turnips were vegetable outlaws, special spawn of Rhode Island, exotic in the proud and debased way of that state. They tasted good and barely edible. Fun to eat, like eating a chair. Jane picked out a dozen — purple grading to yellow and more solid than apples. Propped on the hood she skinned each with a pocket knife. From the blade sprang one continuous skein that Ruth telescoped back to a shell of a turnip, a black joke on turnips. Jane sliced the flesh up into slick fat coins. The coins perspired starch and were for biting designs into. Jean bit hers into moons. Ruth bit hers into frowns that were moons and copycats of Jean’s. Invention for Ruth was a kind of trouble. At the rest stop Jane bit hers into a three-story house using her eyeteeth for windows and widow’s walks and sleep-in porches. Save it! said Ruth and Jean. Give it here! they said and they pleaded shellac it and make it an ornament, but Jane chewed it up, smiling with metal-packed teeth.

It would just go bad if I did, she said.

Jane’s teeth were crafty but her hands were famous. Until the girls walked she sewed all of their clothes. She knit mittens that doubled as puppets. Bent coat hangers into halos and wire-frame wings and wove yarn wigs for Halloween — how the other mothers fumed. For Ruth’s sixth birthday she constructed an angel-food castle with a chocolate drawbridge operated by widget. Boiled lollipops for stained glass. Oh my, said the other mothers when their girls told of it. The basement was feral. Plastic paneled and ceilinged in scabietic pipes — its ugliness inspired Jane. From those pipes swung unoccasioned piñatas of newsprint dredged in flour glue. The girls’ guests clubbed them. Also from the pipes was Jane’s gift-o-matic. The girls’ guests drew numbers. They tugged a corresponding string that dangled and worked a pulley that let down a gag gift — a calico frog stuffed with lentils. Jane sewed, stuffed, and rigged it.

Once a month, at Building 19, laserlike in that headache hangar, Jane pawed the priced-to-move ends of fabric bolts.

She made Italian ice with a hammer and syrup.

Any day of the week, any guest of the girls would not leave giftless.

The girls’ guests loaded up in a bewildered frenzy.

Jean and Ruth could give no explanation. They said of Jane only, She likes to do it.

Your mother can make anything out of anything — this from the other mothers, who knew Jane from the distance of the uncrossed yard. The mothers waved from the car when dropping off or collecting. When Jane spoke to them, it was by phone in the kitchen with her back to Jean. It was about when to drop off and when to collect. With stagey gestures — fending off favors or gnats.

Jean watched these calls in the crossed-arm pose of a cop.

After, Jane would say, That woman buys six-packs of underwear when her maid goes on vacation. A medical doctor who can’t operate a washer.

Or sometimes, mad: What are you looking at?

Jean’s mother never cried.

Her sister never cried.

Her father never lied.

Jean lied sometimes and cried often, so strong-lunged and bestial that Jane could do nothing but close her in a cold shower clothed. She got Jean in fast with those fast-thinking hands — the way she crushed spiders or plucked out teeth.

For Ruth, the trouble was not crying but wiseness.

Don’t get wise with me, Jane said, and it was not water to cure it but a slap to the face. She was slapping her own was the feeling you got.

Ruth took it and walked, uncured. Like she had appointments in that house to keep.

In her lonesome immunity, Jean held her own hands.

In the car to Woonsocket, Jane told a story about an orphan girl adopted by a thieving man. In the story, everyone poor was good and French. The best ones died of galloping consumption. Jean assumed it was the story of Jane’s life. Assumed this although they were on the road to Jane’s still-breathing parents. When Jean was grown she said as much to Ruth — remember how Mom used to tell us her life on that drive?

It was Ruth’s burden to be right (which came down to being attentive and unforgetting). By its inattention and forgetfulness the world contrived to pain her. She lodged her complaint by keeping her voice low. At her most right and pained, Ruth was an alto. In that low way she said to Jean, That was the plot of Les Miserables. You know it. You’ve seen it. We saw it together.

Jean felt ill then with theft — felt that someone had seized, with legal warrant, what she had wrongfully owned.

Tell it again, said Jean and Ruth in the car as soon as Jane finished, but Jane always said, I can’t. We’re here.

Woonsocket was danceable.

You could feel it: a committee of adults colluding to please you, for reasons that preceded you and were certainly not you. Your pleasure, it was clear, was the outcome of a treaty.

Woonsocket was cigarettes and fudge, dogs and dress pins.

The fudge was undercooked, the dogs frenetic.

The dress pins were rhinestone ladybugs set on felt velveteen, and Nana D. would show them shyly and sometimes give them up.

You ate until your stomach was a pendulum and its upswing toppled you.

The neighborhood had the lying-low breathing of the recently bullied. You sensed the triumphal exit of earth movers. The land had no features but crowfoots and newts.

The houses on Nana and Esther’s street looked like the town you’d make, bored, with old school milk cartons. Like every fifth on the street, their house siding was mint.

And behind it: old persons, the significant ones fitting in ready-grin teeth the moment that Jane killed the engine out front.

Guess who ruined the fudge! Nana D. greeted them this way. We’ll eat it with spoons.

She stood back-to-back with Ruth and beat her by only inches.

That grin as athletic and jazzed-out as a tap dance. Nana did somersaults on command. That’s enough, said Jane. Let Nana D. be.

Charming Nana!

Attached to a cigarette was the other old person of note, Aunt Esther, with a bullfrog’s mesmeric perseverance and register — stay stay stay stay STAY — and attached to her by that leash of voice were three Boston terriers. They speed-skated linoleum. They dropped glutinous plumb lines of spittle. Esther’s hands took turns, one on cigarette detail and one off duty interred in a pot of shea butter.

Be good, Special, or I’ll put you down, my love. Esther said this to her favorite, Someone Special, and then her bones, slip stitched in khaki veins, shuddered.

Jane and Nana would cry, Don’t laugh, don’t laugh!

Esther laughed as one giving out.

After, she’d have to lie in the bedroom and hook up to the tank.

The oxygen tank with tattling sighs reinflated her.

Jean and Ruth fitted soupspoons of fudge in their mouths.

Woonsocket was one marathon baptism.

It was as if Jane could not bear to see them there dry. Like it was her mission to liquefy all points of contact.

Woonsocket was a slugfest of low-rent water fun: hose, sprinkler, wading pool, bath.

With the hose and sprinkler you turned the scant apron of backyard to slaphappy mud.

In the pool you drowned newts you mistook for aquatic.

In the bath, you machined products. You conducted science. Every cream, lotion, shampoo, and shaving soap pestled to paste and rolled into straight-to-market beauty pellets, gray from your skin, whose benefits you evangelized hard to Nana D. Close your eyes and just feel this, you’d say, and snail the pellet down the loose sleeve of her arm skin.

Ooo! she’d say, the easy mark, but sometimes too soon. You’d have to scold her.

Gramp was a sweatered installation in a La-Z-Boy knockoff. His hue was tobacco. The chair was balding, the sweater misbuttoned. If it weren’t for the eyes and hands, you would think him asleep. The fingernails were claw thick and injurious as weevils. They worried the armrests, found loose thread and pulled. The skull was fixed on its axis and handsomely armed in a spring-loaded pompadour. Inside the eyes swiveled. They saw people as columns of darkness moving in with agendas to part him from that which he still held rights to, that chair. They saw dogs as avengers. The eyes were watchdogs for dogs and alerted the hands. When a dog entered the room, one hand leapt up to puppeteer a mouth.

Gramp’s hand growled. It nipped the air. The nails of it gnashed.

Feel lucky? Gramp said.

Someone Special skated backward.

Every bath was a plenary session. Esther rested, but Nana and Jane attended. While Ruth took hers, Jean moved in on Gramp with a spoonful of fudge.

Open up, she said.

She held the spoon to the mouth. With one fervent hand she parted the lips. The teeth within were his last defense.

Open up, you pickleworm, she said.

The self-acting hand on the armrest tensed. In Gramp things roiled. Kicked up a bad sediment.

Telepathic Esther, hooked up out of view, knew. Stay stay stay! she called from her bedroom. Thrush, you stay or I’ll put you down!

Jean put down the spoon.

Gramp’s eyes beheld the sun-stroked yard with speculation.

Feel lucky? Gramp said. Soon the white stuff will be coming down.

Why does he always say that? said Ruth in the hall. It’s June.

Jean watched Gramp’s eyes roll to show their white backs.

Keep luck on her toes. Make her feel lucky. You said that. Your skin was gone that skim-milk blue. May I never drink milk. You said luck must like my looks, me hanging on, unfevered, so keep her. The blood wormed thickly out of your ears. Stained the ticking. The wild dogs outside were numerous, plunderous, rooting the earth where I buried Hank. They let out moans like humans rutting. May I never feed a dog. March of ’19 was the Spanish flu. Every door in Fourchu marked out for quarantine, a wet tar X in the hand of that pink-eyed Halifax officer. Fourchu occupants jailed to their sick house. But lobster would not haul themselves — get what’s ours before it’s got, you said. So we got out and got it. Now the March earth hard and Hank dug too shallow. You yelled to dig your grave deeper from the sickbed window. Stand in it and let me see how deep. I want to see just the rims of your eyes. The ground was hard and I was tired. I was twelve. Eleven graves, one for every year I’d kept on. This my first to dig alone. Yours will be my last, I thought. So I crouched. I cheated. You see me, I called, it’s up to my eyes! May I never have to sweat to eat. A tip, you said: Pay luck no mind, then pay her mind when she’s given up. When her value’s down. Buy low, you said. Timing is all. How do I pay luck mind? I said. Me twelve and you sixteen, my last and my least. Your lungs two sets of lips gummed and smacking. Two drowning mouths inside your chest. Smack smack. It made me ill. The sound of me overboard that once, just us two. I was eight. Ma just passed and Da long gone. I was drowning before you. You docked the oars in the wherry and studied me. Your eyes an odd annunciation. Some new truth: paler than I knew. I scrabbled for the surface, beat the water with my fists. Try harder, you said. Try harder, you said. You stabbed the oar at my hand on the corkline. I pawed the tumblehome. You rowed from reach. The waters swallowed me. They had taught you swimming this way too. Chester taught you and Lloyd taught Chester and Tom taught Aubrey taught Donald taught Hank taught Fred taught Cyril taught Clint taught Lloyd. The water closing its cold throat above me. Light spilling down, a shafting liquid. I beat through that to air and saw in your eyes that you did not like me. Indifferent eyes. Not blue blue but skim-milk blue. May I never drink milk; may I never be beholden to one who never liked me; may I ever be a gift to the one who does. To spite you, my lungs on the spot grew feathery gills. I went amphibian. I kicked away from you and straight for the bottom and lay there amid soft and soundless decay for three nights straight. I chewed on substrate. I became a bottom-feeder. A human lobster. And when I returned to that house, you could no longer touch me.

Then I was twelve, unfevered, and it was your turn to feel death upon you. Gag up blood yolks in the bucket I held. What you had left was an hour maybe. You were drowning on blood, my last blood kin, who never liked me, and the last order you gave was the one I did not keep: Dig me deeper than Hank. If you let the dogs eat me, I’ll kill you myself.

If you could you would. But the dead can’t kill.

The wild dogs ate you five feet before me and yet I breathe.

I quit Fourchu.

What I did, I joined the rummies.

The Boston Rum Row syndicates are onetime banana boats, battered beam trawlers, tramps, schooners, bankers, yachts, all rust-faced fugitives from the knacker’s yard. Swivel’s freelance. He’s got an ex-navy subchaser. He rides it at anchor five miles off shore. The syndicates unload faster and funner — call girls board who double their shoreside price, a hazard bonus is what they call it — but Swivel’s dependable. He pays the go-through decent.

I’m seventeen and a go-through man. My little flat-bottom skiff I call Tortoise. Never show your cards in a name. Her payload is fifty cases. She docks in the mud flats, down past the busted molasses tank. Flea sedge and spike rush give good cover.

Sundown, I pull out with the sunset fleet. Go-through jobs sprung from hidden coves zip across the three miles of U.S. territorial. I move with them at twenty-five knots. Hail the mother ship. Pull alongside. Pay off the supercargo. Load to the gunwales. Wave to the Coast Guard revenue cutters: Spanish-American War relics with coffee-grinder engines straining flat out to make ten knots. Designed for iceberg patrol is what they are. The poop-along ladies. They count tonnage, wave back, sleepy.

At the landing point, the Stateside agent’s there with his convoy. His work gang unloads. His gunmen smoke and suck cream from éclairs.

Here’s the math: Swivel buys up Scotch for eight dollars a case at St. Pierre; sells it off Rum Row for sixty-five to the agent who sells it to bootleggers for one hundred and thirty. Landed price is at least double. Now, shoreside bootleggers doctor it three to one, turn around the eight-dollar case for four hundred. National Aridity is a regular wet nurse. She suckles the good and the bad alike. Even the Coast Guard men in their picket boats score — it’s promotions and promotions, a gravy train.

It doesn’t even take luck. If you were a fisherman yesterday, today you’re a rummy.

For one year straight, everyone’s happy.

But spring of ’24, the Coast Guard and Congress make a resolution about balls. How they adore them and want to grow some. They get ideas. Idea number one is to push back the Rum Line from three miles to twelve — thinking to put the Row out of reach of us small craft. Some, it’s a fact, can’t do the distance. But Tortoise is tight as ticks. Idea number two is hire on Swedish merchant seamen named Lars, their two words of English yes and put-put. Idea three: Take twenty-five destroyers out of retirement. Thousand tonners, moving at thirty knots. Mounted one-pounders for close-in work. These take station at mile twelve, to breathe down hard on the necks of Rum Row. And behind them at intervals the bad news for go-throughs: flotillas of six bitters and picket boats. Shoreside sand pounders haunt the beaches.

Now luck counts. So I make luck want it. I go bold. Push Tortoise harder. Go after dark, cloud cover, no lights, trust luck to steer us shy of sandbars. Those who woo luck wrong get boarded. Too much sissy foot unmans you for luck. If you’re outward bound, tossing salt over shoulders and twiddling hare foots, cutters will surely find fault with your life vests. They’ll ask for documents. They’ll take two hours to analyze handwriting.

God likes the bow and scrape. He cuts deals for toadies. Well, I dance swell, but not on my knees. I take instead luck. Luck is a call girl who likes my looks and my steps. Sometimes a slap. But sometimes all that fatigues a man. Here was my misstep running go-through for Swivel. I became too cozy. I drank up the days, dillydallied my runs. I misread the weather. One day in June I saw them: clouds banked up against the sky, green-gray, sun showing as through a film of ground glass. Wrong clouds for Tortoise. Tortoise hates snow. I foresaw the snow, but who would believe it — it’s June, you fool, I told myself. I discounted the clouds and drank my cut brew. I stewed off the day. But the light filtering down through cloud cover blurred me, and, like

a fool, when at sundown I pushed out I by accident prayed. Pleasebetogod-letthepissfuckingsnowholdoff. To what in hell was I praying? No matter. I two-timed luck. And for that one day, luck didn’t want me.

The waves are steep at mile twelve and snow comes hard as Swivel’s men hand down the last case. On your mark, the revenue cutters. They skulk up, lights off, tonguing your way, lappity lap lap, and you might think it’s fish. You might think big game. But it’s not halibut. It’s picket boat. Swivel signals it. And me already loaded up fifty case. Cut the engine, Swivel says. Give the wheel a turn to port and lash it, says he. Lappity lap lap. Lappity lap. And the cutter closes in and then pisses off. Nothing. Hoopla.

Trouble is, I’ve drifted. Can’t see for snow. And the engine, overloaded from a dead start, labors. I’m misdirected in bad sea, shoved headwise to Swivel. Twenty footers and my prow blowing Swivel’s stern. The blessed romance of it. A row of pale patches where the faces of Swivel’s men glow watching from the subchaser deck, immovable. The air hurts. My engine won’t catch. Then the hit. Glancing, and my pilothouse lays out sideways. The rail swoons starboard, buckled down flat to deck. By the moon — it’s high — about two ante meridiem. Not a good hour.

Nor the worst. If the wave had hit any sooner I’d have nailed the counter of the subchaser square and been gone. Instead I beat death to the punch and dove.

To all eyes I disappeared for good. The water took me.

But did luck take me back, a lobster?

You judge.

I drifted the bottom for three nights straight.

It was so soft down there and so soundless.

I was a goddamn peaceful crustacean.

When I at last surfaced, I met luck herself. She had taken the body of a flat-chested kid. Younger than I thought and a good deal odder. She touched my cheeks like they were flesh, not shell. She laid her body on mine like ours were one body. So close was she, my eyes could not converge to see her. She doubled before me. When she spoke, I could not say from whose mouth the words came: I paid for you and you’re mine to keep.

Drink hulled Gramp’s brain. When Jean was grown, Jane spoke of how Nana was going to put Gramp in a home, but Esther said keep him for the pension check. Wasn’t it Nana’s house, her say? asked Ruth. Jane said it was not. The house was Esther’s, Eddy’s when he lived, willed him by Alice. Thrush would have hated nothing more than to know he lived off Eddy’s good graces.

Soon the piss-fucking white stuff will be coming down.

As if to back him, Gramp’s eyes showed only their whites.

Nana D. came in from the bathroom and stood before him. When Nana’s hand touched his cheek, Jean saw him shiver.