essays

The Secret History of Cricket Magazine, the “New Yorker for Children”

Kids in the ’70s needed a magazine that didn’t underestimate them, and they still do

No one answers the phones at Cricket Media.

The company has fully embraced the opaque, untouchable nature of most contemporary companies: a pretty website, a menu of general email addresses, and a fully automated phone system.

You press 1 for one set of publications, 2 for another, 3 for the dial-by-name directory. Or you can hold the line for a receptionist who simply doesn’t exist.

In the course of researching this story, I’ve dialed many names, held the line, emailed addresses both general and specific, and tweeted at Cricket. But I failed to reach anyone who currently works there.

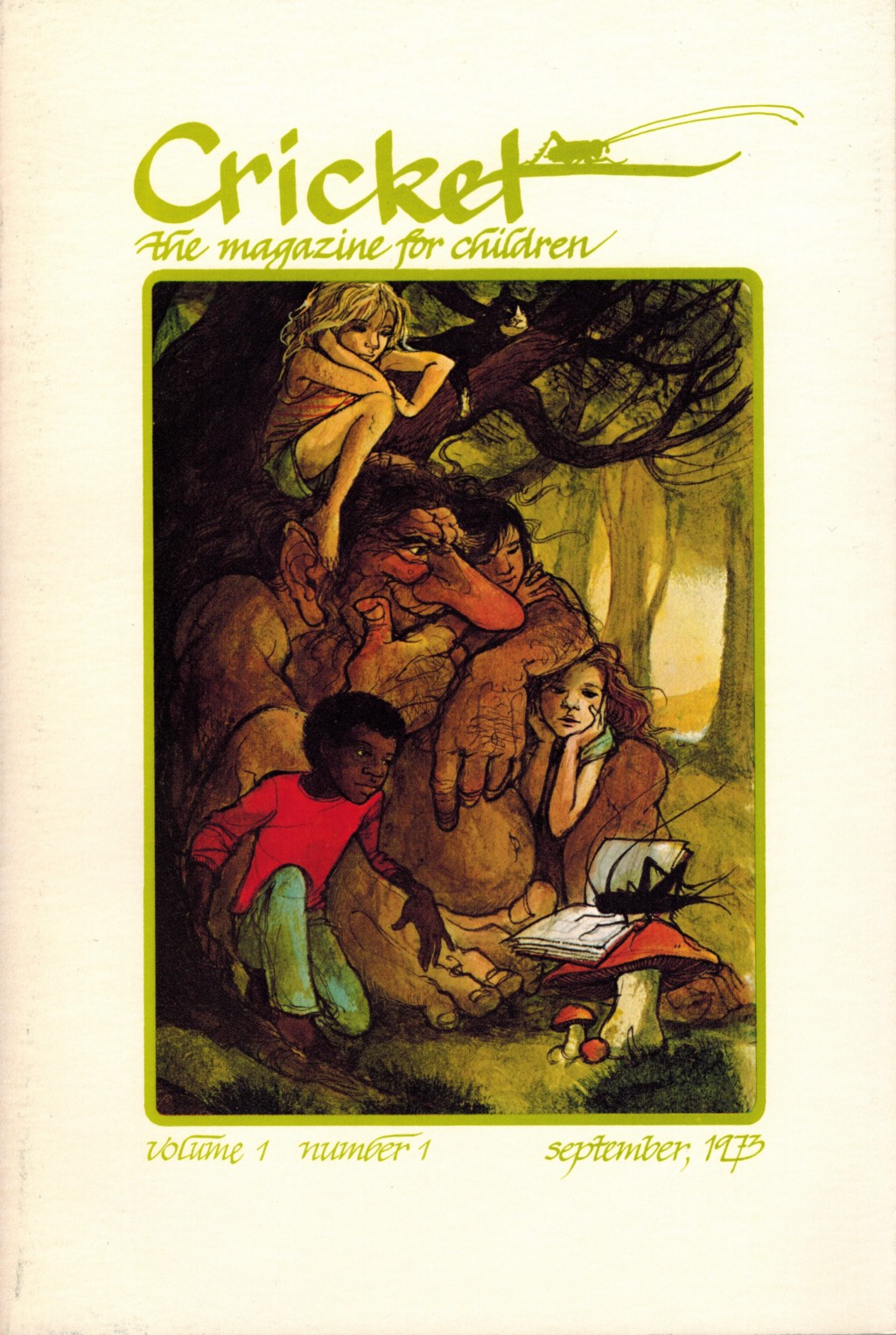

Cricket wasn’t always so unavailable. Founded in 1973 by an educational reformer, Cricket has been accessible to so many children for the last 44 years. Generations of young readers cut their teeth on the pieces in Cricket: work by writers like Lloyd Alexander, George Selden, Ursula LeGuin, and Julius Lester.

In a time when children’s magazines mostly featured hidden object drawings and games, Cricket stubbornly refused to underestimate its young readers. It welcomed their correspondence, and was such a human endeavor that for many readers, finding Cricket in the mailbox every month was like a visit from a friend.

Cricket stubbornly refused to underestimate its young readers.

Kelly Link, whose collection of fantastical short stories Get In Trouble was a Pulitzer finalist in 2016, loved Cricket so much as a child she’s kept all of her back issues — she could not bear to get rid of them. Cricket influenced her to become a writer “one hundred percent,” she says, and more than that, nudged her toward writing short stories.

“[Cricket taught me] that poetry and short stories could be playful,” Link said. “That you could write contemporary short stories deliberately. That I liked some short stories better than others, and I especially liked stories of the fantastic.”

Laura Newcomer, a professional writer and editor, also read Cricket as a child. She loved that the magazine felt like it was written for her.

“I was an intelligent and extremely imaginative kid, and I felt like the magazine didn’t patronize me. Instead, it felt like it celebrated me and other kids like me, and provided a space for us to come together and be smart and imaginative together,” Newcomer wrote to me.

That sense of kids being taken seriously was no accident. It was the whole idea.

In the early ’70s, Marianne Carus received a submission for her fledgling literary magazine. It was from Astrid Lindgren, the creator of Pippi Longstocking. The submission was part of her manuscript for her latest novel, The Brothers Lionheart.

It was a children’s book, but not a happy one: within the first three chapters, the titular characters both die and go to the afterlife; the older brother sacrifices his own life to save the younger in a housefire, and the little brother later dies of tuberculosis.

Carus read it, loved it, and decided she had to publish a portion of the book. It was excellent literature, and that was what she wanted in her newest endeavor, Cricket, a literary magazine for children, a curated collection of the cream of children’s literature, that would eventually come to be called “The Little New Yorker.”

When Carus, now 89, talks about her philosophy in creating Cricket, she paraphrases English poet and children’s author Walter de la Mare, saying only “the rarest kind of best in anything is good enough for children.”

“We only accepted stories and art of the highest quality,” she said. But “the rarest kind of best” and “the highest quality” didn’t always align with what people thought was appropriate for children.

Carus’s staff balked at The Brothers Lionheart. The story’s themes of death and disease seemed too dark for a children’s magazine.

Her art director called to tell Carus that the new magazine could not publish the story. It was too dark, and too sad. Carus was unmoved.

Her art director, Trina Schart Hyman, called from her home in New Hampshire to tell Carus that the new magazine could not publish the story. It was too dark, and too sad. Carus was unmoved.

“I said ‘Trust me, Trina. I will have it in Cricket,’” she said. “So we did.”

Marcia Leonard, then on staff as an assistant editor, remembers not loving the story, less because of the themes and more because of its presentation, but she also trusted Carus’s judgment.

“Although Marianne sought her editors’ opinions, we recognized that she was in charge and the magazine was her baby, so she made the final decisions,” she wrote in an email.

There was no watershed moment when Carus, a German immigrant and mother of three, decided to found a literary magazine for children. Instead the magazine was born out of a cluster of enterprises, pressures, needs, and about 13 years of interest in educational reform.

It all started when André Carus, the oldest child of Marianne and her husband Blouke, started first grade for the second time in the fall of 1959. He had already attended school in spring of that year, when his family was on a year-long trip to Germany. When the Caruses returned to Illinois, his parents were appalled by the repetition and the limited vocabulary of the Dick and Jane books he was given to read in school. That experience prompted the Carus family to launch the Open Court Readers, a reading curriculum that relied on phonics and engaging reading material.

Starting publications is a Carus family tradition. In 1887, businessman Edward Hegeler — Blouke Carus’s great-grandfather — started the Open Court Publishing Company. The original goal of the company was to publish two journals: The Open Court, a journal which aimed to reform religious thought using the principles of science, and The Monist, a philosophical journal. (The Open Court put out its last issue in the 1930s. The Monist is still published today, now by Oxford University Press.)

So when the Carus family, in the early ’60s, decided that their son’s reading material was substandard, they used the family publishing house to publish the Open Court Basic Readers.

Blouke Carus is an engineer by training, but absolutely dedicated himself to improving the U.S. education system. He found himself up against not just the Dick and Jane see-and-say method of teaching reading, but inertia in the educational system.

It’s been a long battle. When I reached Marianne Carus to talk about Cricket, Blouke had left their home in rural Illinois to go to Washington, D.C. to talk to education officials.

“He’s 90 now, my husband,” said Carus. “But he’s still very young at heart, and very fortunate that he can still travel to Washington and talk to the most important people there. They listen to him, but they don’t do very much about it.”

While the Open Court Readers were Blouke Carus’s project, Marianne was brought in early on as a kind of tastemaker. The Open Court Readers focused on phonics paired with good reading material, so that children would be interested in reading. Marianne, who studied literature at the University of Freiburg, the Sorbonne, and University of Chicago, knew good work when she saw it, and was able to identify selections that should be included in the readers.

Carus is one of those rare adults who seems to understand children; when you talk to her about the choices she made as Cricket’s editor, she draws on her own experience of being a child who loved to read.

“Short reading material is very important. It gives you a certain sense of accomplishment if you finish a story or if you finish a short book,” she said. “When I was a child, and I was reading one book after another, I was very happy when I did finish a book and didn’t just leave it because I was not interested in it anymore.”

She founded Cricket because in her work with the Open Court Readers, she discovered a dearth of good short material for children.

In the early 1970s, there were about 100 children’s magazines on the market. None of them carried great material, in Carus’s opinion. She recalls reading Highlights for Children to André when he was sick with a sore throat. Highlights did the trick — it put him to sleep. It also put Marianne to sleep.

“I was reaffirmed in my belief that children needed something they would stay awake for,” she said.

‘I was reaffirmed in my belief that children needed something they would stay awake for.’

Carus modeled her new project after St. Nicholas Magazine, a literary magazine for children which ran from 1873 to 1943, and had been edited by Mary Mapes Dodge, the author of Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates.

The magazine began in 1972 with a small staff: Marianne and a part-time secretary worked on-site in the company’s office in LaSalle, Ill. Trina Schart Hyman, whom Carus had met at a book fair and hired as Cricket’s art director, worked remotely from her home in New Hampshire, sending her work in through the mail.

Carus also brought on an editorial assistant, Marcia Leonard, a recent college graduate with a degree in children’s literature. Leonard had been taking a summer course at Radcliffe in magazine and book publishing when one of her classmates showed her an ad for a new children’s magazine. She had been planning to go to New York, but she couldn’t pass up an interview with a new children’s magazine in her home state of Illinois. So she drove out to LaSalle, a little town in farming country.

“After I talked to Marianne about the magazine and her plans for it I knew I had to be there,” she said. “That was very exciting, to be in on the very beginning of something.”

Carus asked Leonard to commit to two years. Leonard promised one. She was there for six and, in that small office in that little midwest town, Leonard received a more rigorous training in editing than she might have gotten in New York.

“Marianne was a great mentor. She would sit beside me and go through a manuscript I had edited and she would talk with me about [why I made the edits I’d made]. I learned tremendously from that experience,” said Leonard, who is now a freelance editor and the author of more than 100 children’s books.

In 1972, Carus, Hyman and Leonard put together a pilot issue of Cricket. There was only one problem with it: Drawing from the example of St. Nicholas, the magazine’s titles were hand-lettered, which made it hard to read. So Carus brought in a designer: John Grandits.

While Grandits, who is now a children’s author, started with the Carus Publishing Company as a typographer, he quickly learned through working with Carus and Hyman a truth about Cricket’s philosophy: good storytelling wasn’t just about the printed word. The stories should be linked to the best illustrations possible.

“Illustrations are a speciality field, and in ’73 there were many great illustrators still working and still alive and Trina was able to corral them and get them to work,” said Grandits, who later became Cricket’s art director and took the magazine from its original 6 by 9 size to its now-iconic 7 by 9 format.

All of the artists in Cricket were remarkable; Grandits recalled one conversation in which Wally Tripp painstakingly explained how to correctly alter a horse’s anatomy so it could be anthropomorphized.

“He says, ‘Well, horses have hooves. They have no opposable thumbs. If you’re given a story to draw with a horse, how do you resolve the thing where he has to have a top hat and cane? He can’t put the hat on. He can’t hold the cane. What do you do? There’s a lot of illustrators who sort of lay it nearby, and it looks as if they’re holding it maybe, and nobody ever addresses the question of how the hat got on the head. But what you have to do is make adjustments to the anatomy of the horse.’ So he said, ‘Here’s a horse skeleton.’”

Tripp sketched out a horse skeleton in the dust of the fireplace where they were sitting. He went on at length, about how many fingers a horse should have, and how the cleft part of the hoof could work as an opposable thumb.

“He’s worked through all this, very seriously and very sensibly,” said Grandits. “There are big problems you have to solve if you want to draw this with honesty and honor.”

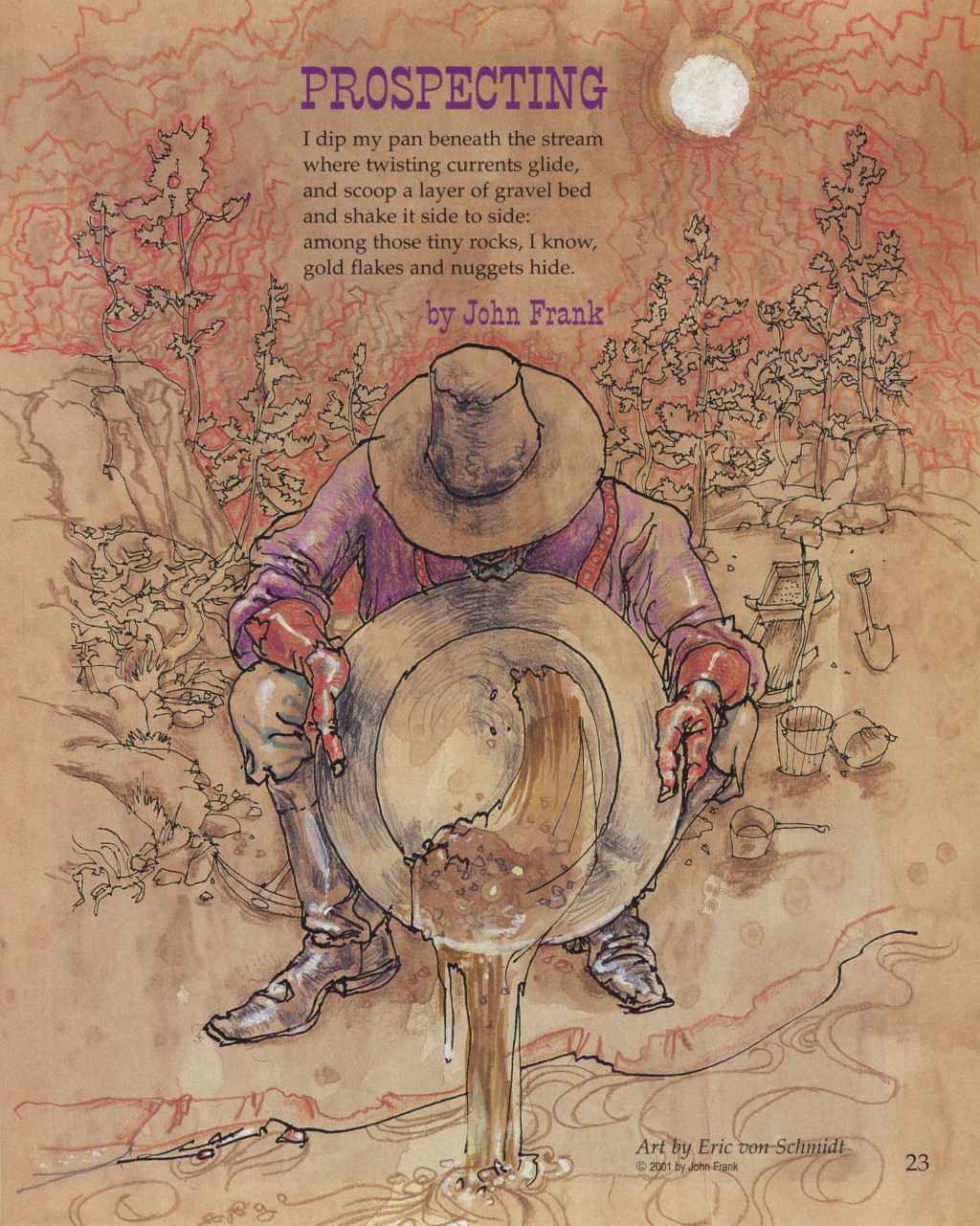

Another of Cricket’s artists was the late folk singer Eric “Rick” von Schmidt. Singer, composer, friend and collaborator to the likes of Bob Dylan, von Schmidt was also an artist. His work can be seen on album covers from the ’60s, but also within the pages of Cricket.

The first piece he did for Cricket was in 1979, said Caitlin von Schmidt, who is herself an artist. (She began reading the magazine that year, when he started working for them.)

“It was all storytelling for Rick,” said Grandits. “You tell stories with your pictures, you tell stories with your songs.”

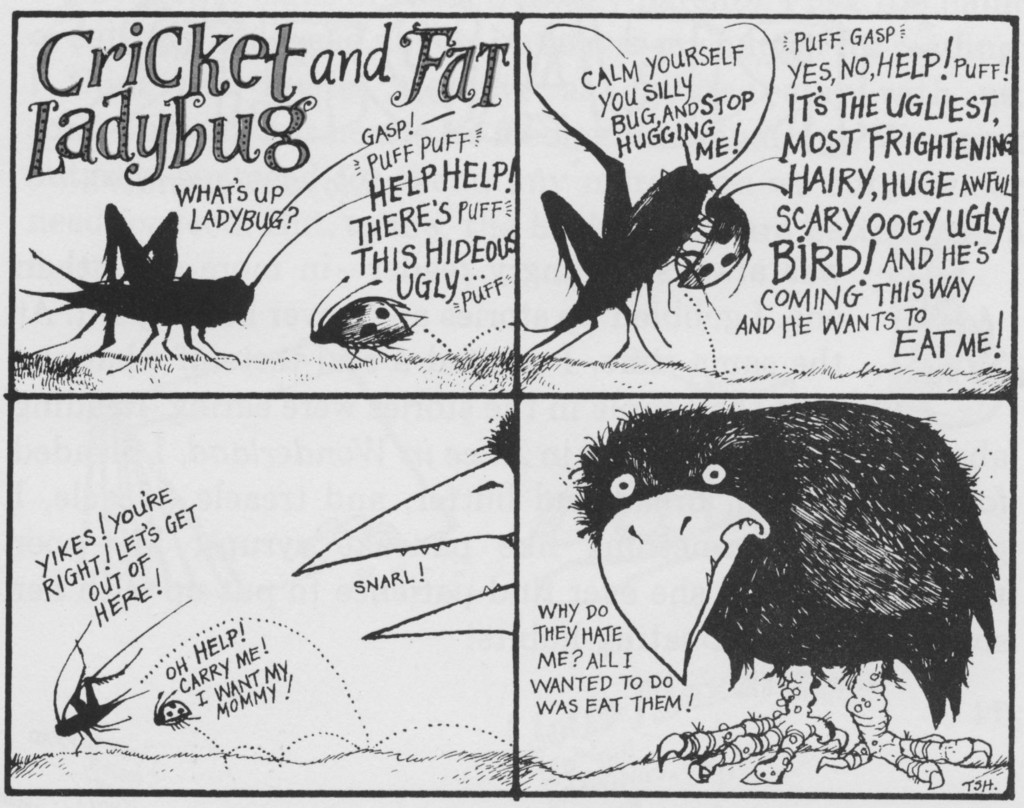

Hyman herself, who died in 2004, was an incredible artist. Her dreamy, detailed drawings won her the Caldecott Medal in 1985 for her work in St. George and the Dragon by Margaret Hodges. (She also garnered three Caldecott Honors.) It was Hyman who drew Cricket, Old Cricket, Ladybug, Sluggo, and all the other bugs, worms and spiders that still crawl, wriggle and jump through the pages of Cricket and its sister publications.

“[Trina] just had such a wonderful way of drawing them,” said Leonard. “They served as explanation of difficult words so if there was a vocabulary word that might stop a kid reader the crickets would explain what that word meant. They also had their own little life in the four-block cartoon.”

The Brothers Lionheart was published serially in 1974, beginning in Cricket Vol. 2, #12. The response from readers affirmed Carus’s decision to include the excerpt in the magazine. A Librarything review from 2013 describes having read the first installment and not being able to find subsequent issues of Cricket to finish the story.

“Oh how I suffered, not knowing what happened to the two brothers who jumped out of their burning house to what seemed certainly to be their deaths, ” wrote user anderlawlor. “Then in 2002, I was working at Dog Eared Books in San Francisco and someone brought this book in to sell. One of the best days of my life. It actually holds up to twenty years of longing.”

‘Kids love to cry. I wanted to cry too when I was a child.’

Susan Bernofsky, a translator shortlisted for the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation for her German to English translation of Memoirs of a Polar Bear by Yoko Tawada, was a voracious reader of Cricket as a child. She remembers The Brothers Lionheart as a particular favorite.

“I think I loved it so much because of the sadness and the modeling of how to deal with sadness with love and grace,” she told me. “I loved the picture the story painted of fraternal love, and the idea that somebody could send a message of love from beyond the grave.”

Carus, in giving children credit for being able to respond to a range of emotions, had made the right decision.

“Kids love to cry. I wanted to cry too when I was a child,” said Carus. “And in some ways, it was a relief, to be able to cry about something. Just as it is a relief to cry about when you are very very happy.”

Children — like Link, Newcomer, and Bernofsky — responded to the trust that Carus showed them. They wrote in en masse, often addressing their letters to Cricket and Ladybug, sending story suggestions, recipes, and letters. One child, said Grandits, found a cricket in their home and mailed it to the bugs “as a friend.”

“The response from the readership to the magazine was phenomenal,” he said. “These kids took this thing very personally… from very little to very mature, kids would write to us.”

“Cricket was a gateway drug to The New Yorker,” said Sarah Burnes. Burnes — now a literary agent at The Gernert Company — read Cricket cover to cover when she was a child. She loved the stories and conversations between Cricket and the other bugs.

‘Cricket was a gateway drug to The New Yorker,’ said Sarah Burnes, a literary agent.

“It certainly played a big role in my becoming a fanatical reader of both magazines and books, and then an English major, editor, and now agent,” she wrote.

“It sounds cliche, but I think the word ‘transported’ applies to my experiences with reading the magazine,” said Newcomer. “I eagerly looked forward to its arrival and could get lost in current and back issues (I saved every single magazine for years) for hours. It was like entering a flow state through creative consumption as opposed to creative output.”

Bernofsky began reading Cricket as a 7-year-old in 1973. Her mother, a teacher, learned about the magazine before its official launch, and subscribed Bernofsky and her younger sister to Cricket, starting with the very first issue. She read each issue multiple times.

“I still remember some of the drawings and poems and stories today,” she said in a Facebook message. “There was a little poem ‘Pity the girl with the crystal hair, how can she run, how can she bicycle?’…I could probably still recite most of it.”

André Carus went from being the inspiration for the Open Court Readers to being their publisher; he managed the Carus Publishing Company (Open Court’s parent company) from the mid-’80s until 2011.

It was during his tenure that Cricket’s magazine family expanded to include its 14 sister publications, including the other “bug” magazines: Babybug for babies, Ladybug for toddlers, Spider for small children and Cicada for teens. There were other magazines as well: Grandits and his wife Joann were brought back to Carus Publishing to launch the nonfiction magazines Muse and Click.

When I reached out to him for this article, Carus was willing to be interviewed, though he asked me to do some homework first. He wanted me to read a 2006 book called Let’s Kill Dick and Jane: How the Open Court Publishing Company Fought the Culture of American Education, written by Harold Henderson.

The book, commissioned by Carus, is less about Cricket, which is mentioned just once, and more about Open Court Readers and Blouke Carus’s quest to reform U.S. education. In fact, although Carus was attached to the magazines, he feels the textbooks were the greatest contribution to education in the U.S.. The Open Court Readers, he points out, made a difference to disadvantaged children who needed to learn how to read. Cricket was aimed at a demographic that would probably have been literate anyhow.

I asked Carus, now 64, what it was like growing up alongside his parents’ publishing enterprise and educational efforts.

“Oh, I was a believer,” he said. “I think the company made a difference.”

Unfortunately, Carus inherited a difficult business model; magazines are normally supported by ads, and none of the Carus magazines ran ads, relying instead on subscriptions.

The business model was made even more difficult by the rise of the internet. Cricket and its sister publications did move online in some ways: by 2007 parts of all the magazines were available online and electronic versions of the magazines were available to subscribers. That didn’t help, however. Cricket, which had long relied on subscriptions to its physical magazine, had a difficult time finding a way to adapt to an online environment.

Cricket, which had long relied on subscriptions to its physical magazine, had a difficult time finding a way to adapt to an online environment.

In 2011, when it was sold, the company was still fulfilling many print subscriptions. Two thirds of those subscriptions, said Carus, were gifts from grandparents.

It wasn’t enough to keep the company afloat. The Carus magazines had always catered to an audience that was willing to pay a little extra for quality, but there weren’t enough of those customers to keep the company solvent. While the Carus Publishing Group had some success finding new customers through direct mail in the mid-’00s, the 2008 financial crisis dinged it badly. Banks were no longer as willing to deal in cash flow lending.

“If we hadn’t sold, we would have gone bankrupt,” said Carus.

Now that he’s out of the publishing business, he is engaged in another of the Carus family’s passions: philosophy. Carus earned a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Chicago in 2007, and writes a blog dedicated to the work of the German-American philosopher Rudolf Carnap. He now lives in Germany, where he is a visiting fellow at the Munich Center for Mathematical Philosophy.

He seems both saddened and relieved when we talk about the sale of the Carus Publishing Company. He’s finally free to pursue his love of philosophy — he says he never really got any peace until the company was sold — but he’s sorry to have to sell the company his parents built.

The textbooks had already been sold off in the late ’90s. The magazines were sold in 2011 to ePals Corporation, a Canadian digital education platform that would hopefully be able to bring Cricket and the other magazines into the digital age. That company is now called Cricket Media.

Cricket is still around.

I found one of the latest editions in a library this fall, and it’s as well-written and well-illustrated as ever, which is unsurprising, considering that the current editor-in-chief worked with the Caruses before the magazines were sold.

If reviews from current and former employees on Glassdoor are to be believed, the current editorial staff still cherishes the values held dear by Cricket’s founders, although the management is struggling with the realities of magazine publishing.

Today’s Cricket is exactly like its namesake. Its output can’t be ignored. But if you’re trying to find the cricket itself, good luck.

There is a hint in those reviews that the current owners might be educational reformers in their own right: one review talked about the owners’ vision for school-wide technology and their conviction that the way students are educated must change.

It sounds quite familiar, but I never found out, of course.

Cricket is named for a scene in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s A Day of Pleasure, in which a cricket in the house chirps all night, “telling a story that would never end.” Today’s Cricket is exactly like its namesake. Its output can’t be ignored. But if you’re trying to find the cricket itself, good luck.