interviews

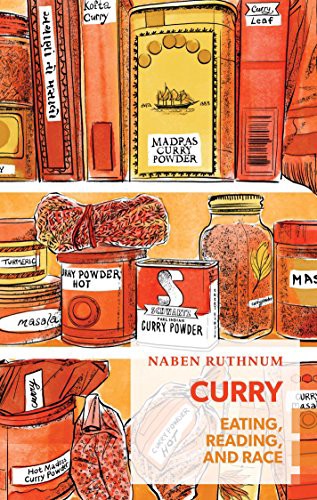

The Secret Life of Curry

Naben Ruthnum writes about South Asian identity and literature by way of South Asian food

What is a “currybook”? Canadian author Naben Ruthnum coined the term to describe a particular kind of diasporic writing that combines easy South Asian cultural touchpoints, swaths of old world nostalgia, and a vague sense of the exotic coalesce beneath a paperback cover — and is then mass-marketed towards both homesick immigrants and curious outsiders.

Growing up in a Mauritian household in sleepy Kelowna, British Columbia, Ruthnum was always unimpressed by the warm rows of these currybooks — their covers tinted orange, plum, or persimmon — that he’d find lining his parents’ bookshelves. As he got older and settled into his career as a multi-genre fiction writer, he began to question his dislike of this particular type of “immigrant as identity” diasporic writing, as well as the publishing industry’s penchant for these so-called “sari and spice” affairs. In Curry, his debut for Coach House Books, Ruthnum set out to investigate his own fraught relationship with curry — as a spice, yes, but more so as a greater symbol of his own identity. He explores how eating curry, reading other writers’ thoughts on curry, and the racialized dynamic surrounding curry play into his own identity as a brown, diasporic writer.

The book is a sort of jumble; it’s part memoir, part literary critique, part culinary history, and part rant, the sort of mashup that makes quite a lot of sense once one considers Ruthnum’s own varied writing background. He doesn’t hold back on his opinions of the more damaging or reductive tropes associated with his target, but pulls no punches when it comes to himself, either. Throughout Curry, Ruthnum grapples with his own prejudices — against currybooks, against their more exoticized, feminized counterparts (which he calls “mangobooks”), against the glut of diasporic novels that felt both too familiar and utterly foreign to his own experience. That penchant for clear-eyed self-interrogation keeps the book from feeling too polemical; instead, it makes Curry all the more accessible, steered as it is by an author who is, quite simply, working through his own shit.

Discussing big, sensitive ideas like identity, authenticity, and the immigrant experience may be a tall order, but in Curry, Ruthnum digs in with gusto.

Kim Kelly: The idea of the “currybook” and your conflicted feelings about the genre is a central theme of Curry. Could you break down what exactly a “currybook” is, and why they’ve become such a thorn in your side as a South Asian writer?

Naben Ruthnum: “Currybook” is a term I had for a certain kind of diasporic brown novel when I was a teenager: the type I didn’t want to read. The way I describe these books in Curry is as “nostalgic, authenticity-seeking reconciliation-of-present-with-past family narratives,” and that tends to spur recognition in readers who know what I’m getting at: often, these books will have drifting red silks and a braid on the cover, or a scatter of powdered spices, maybe a mango or two. And often, as I discovered when reading this book, books that happen to adhere to these rough genre guidelines are well-crafted, heartfelt works of art, not just parroting of the “sari and spice novels” (a more popular term for currybooks) that have come before them.

But the themes and relationships at the heart of these novels didn’t resonate with me as a writer — at least not across all of my work. Problem is, I did write one short story, “Cinema Rex,” that dealt with brown kids on the island of Mauritius in the 1950s and their subsequent, film-obsessed lives in the West as adults — classic ingredients for a currybook, and the first piece that garnered me any real attention from awards juries, publishers, and agents. Many of the people who liked that story were put off by the rest of my work, which ranges from thriller to literary fiction that isn’t always centered around brown protagonists. Pushing forward over the next few years as a writer, I realized that the pressure of expectation to create a literary persona and work that is recognizable as fitting into pre-existing versions of Western brownness, complete with tragic looking back, generational disconnect, and an inability to cook amma’s aloo gobi, was a real part of what was standing in the way of me getting to publish what I wanted.

Wealth and Family in the New India

KK: In the book, you talk a lot about the demands that are placed on brown writers by the publishing industry as well as the reading public — this sense of needing to either seamlessly assimilate or exoticize oneself. How do you think this way of thinking can be effectively challenged? How can the industry make more space for brown writers to be whoever they want to be?

NR: That pressure to exoticize my writing and work in a way that is, funnily enough, actually asking me to conform to a pre-existing story template that we’ve read dozens of time before, a sort of prefab exotique, has been a dominant pressure in my career. The go-to answer to this problem tends to be getting more people of color in editorial boards and agencies. But, as I say in the book, it’s not simply white audiences who gravitate toward echoing, nostalgic stories of brown identity repeatedly: it’s a significant contingent of the brown audience as well, and readers of all backgrounds. So just getting an editor of color to read your book isn’t the magical fix-it to getting stories of unique brown identity in the West out there — or the stuff that I tend to write, which is clearly informed by my racial and class background, but doesn’t often plainly foreground issues of racial and cultural identity. I think the key to getting more space for stories out there is something like a serious version of what I’m doing with this book, where I make fun of and create discomfort in readers and publishing industry operatives who have an extremely narrow internal definition of “diversity.” It has to be an ongoing, and sometimes mean, discussion.

The pressure to exoticize my writing and work is, funnily enough, actually asking me to conform to a pre-existing story template that we’ve read dozens of time before.

KK: The subject of family consistently appears throughout the book, from your own Mauritian clan to the overarching concept of “authenticity.” How did writing this book lead you to interrogate your own relationship with family? What’s the most significant thing you learned as a result?

NR: Family dynamics are so often at the heart of currybooks, good and bad, and there is a very recognizable pattern that many of these books tend to stick to, which often reflects the lived reality of their authors. You know what I’m going to write — conservative parents who don’t understand why their children are listening to rap and sometimes dating white people. I’m being wildly reductive here to get a point across, and that point is that the lived reality of some brown people in the West may fit this pattern — but bring individuality, class, education, artistic leanings, religion, isolation, generational distance from the subcontinent into it — and what you get is an incredible range of different parents and children interacting differently.

For example, the scolding aunties that I see in certain novels are a type I recognize as real, a type that resonates with young South Asian people I’ve talked to — but the closest aunt in my family lived in London, is highly progressive and independent, and was taking me to bizarre Wooster Group plays when I was in university, encouraging me to think and write exactly what I wanted. That extended-family-disapproval thing was never a part of my life, while it’s embedded in the lives of many other brown Westerners.

I did learn, as elsewhere in the process of researching this book, that my initial, childish dismissal of trope-heavy books by South Asians was immature and incorrect. There are truths about family relationships that don’t become any less true from being repeated: it’s just that there are other truths that I’d also like to read about, and they need to be published more often. There are also truths among the currybook tropes about family, nostalgia, and homecoming that are distinct, odd, and hyper-specific, that risk being lost as these books are marketed and promoted as belonging to one mass of shared experience.

KK: The concept of curry is itself rooted in sociopolitical turmoil, stretching from the earliest days of the British Raj to the racism still experienced by South Asian people. How do we decolonize curry?

NR: Pushback is embedded in curry’s recipe, I think. The chilies in Indian curries come from Portuguese traders centuries ago, planted on Indian soil to make commerce with Europe and elsewhere easier: but Indians took ownership of the spice through culinary ingenuity. Adapting the incredible variety of dishes that are classed under the curry banner to Mughal courts and the Raj afterwards expanded the definition while catering to certain palates, but there’s no sense of the colonist owning the dish — I feel that curry is a dish that has the world in it, a historical, evolving food that can’t perhaps ever be properly “decolonized,” but it can spur a discussion for just how complex and worth unpacking these terms and this insane history is. That discussion has to be about making these different historical and colonial paths to what’s on your plate known.

I feel that curry is a dish that has the world in it, a historical, evolving food that can’t perhaps ever be properly “decolonized.”

KK: Your discussion of Soniah Kamal’s essay “When My Authentic Is You Exotic” and the “mangobooks” seemed to hit a particular personal nerve, especially the idea of how diasporic brown people feel forced to police themselves to avoid falling into perceived stereotypes. What is at the root of your (and other brown writers’) professed dread of writing to “serve” white audiences?

NR: I’ll speak for myself, but it’s probably a sentiment many brown writers share — the idea of serving your own banal existence as exotic to white readers, or, even worse, inventing a sense of connection to the past, or a sense of alienation that you might not properly feel in order to create an effect in a white reader that is based on seeing your name and author photo then reading a narrative about an orphan trying to reconnect with their severed homeland — is just plainly chilling.

I certainly try not to let this get in my head too much. Despite having written this book, I do think it’s extremely important for my time spent writing fiction to take place inside my own head and in the story, as divorced from ideas of audience reception as possible. That’s part of what I was working out with Curry: exactly what it was I thought of all this stuff, and how I could find a way to have a career that didn’t involve me trying to outsmart industry expectations behind the scenes. Making my part of the discussion public seemed to be a good way to do both.

Support Electric Lit: Become a Member!

KK: As a writer, what did you seek to accomplish by publishing this book? And now that it’s out, would you say you’ve achieved that goal?

NR: Now that the debate about diversity in literature is loud and ongoing, it’s important to have disagreement-within-ranks about what constitutes diversity, and what the various problems in the industry may be. I had to work against this obstacle personally when it came trying to get my work published, because I kept running into a tacit definition of what brown writing looked like: a definition that my work didn’t fit into. “Being accepting of diverse narratives” risks morphing into an acceptance of “being accepting of THE diverse narrative,” whatever that may be for one’s insert-cultural-group here. Of course, writers like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie have already precisely nailed this problem, and in part, my book was just adding to the work they’ve already done — but the other thing I wanted to do with this piece was to joke, to suggest, to discomfit people, whether they be of color or not, into thinking about these issues for themselves, and not just seizing onto a solution that I myself never arrive at, in the book or in my own career.

And I can’t forget the publishing-my-first-book part of the deal, especially because I’ve been fortunate enough to get press and reader attention for Curry. My selfishness as a writer, my desire to have books out across genres and to write for other mediums, is a motivation that I never want to underplay, and I think that’s useful in making the points I made the way I made them — in talking about the career and aims of an individual writer who is constantly confronted with a genre-cast mold of what he is supposed to writing, I’m telling to story of the racialized writer as an individual, not a type, not a category: a weird person shaped by race and class, certainly, but too many other important and trivial factors to enumerate.