Books & Culture

The Sense of a Happy Ending

The problematic happiness of the film adaptation of Julian Barnes’ Booker Prize-Winning Novel

Signs that you are watching a feel-good movie: a long sequence in which the protagonist opens up the shop where they work; they insert the key in the lock, roll up the blinds, flip the hanging open/closed sign. A tinkling bell announces the arrival of a customer who, by contrast, alerts us to the protagonist’s ennui––whether a klepto who places a books down his pants (Notting Hill), rude customers (My Big Fat Greek Wedding), or an old woman who one-ups the protagonist with talk of her internet sex life (You’ve Got Mail). Further signs: the protagonist attends a lightly comedic Lamaze class; running jokes which involve the mailman, or old men using “modern” technology.

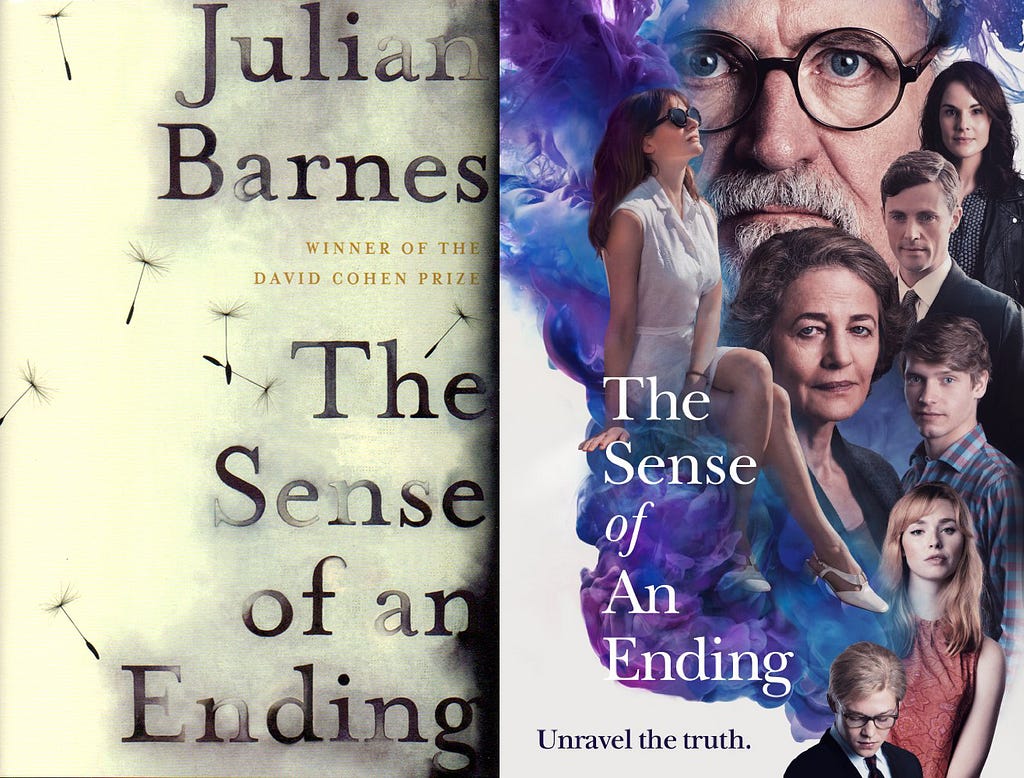

Julian Barnes’ 2011 Booker Prize-winning novel The Sense of An Ending featured none of the scenes listed above. Its 2017 adaptation to film, written by playwright Nick Payne and directed by Ritesh Batra (The Lunchbox), contains every one of them.

Barnes’ novel is the story of middle-aged, middle class British man Tony Webster. Tony narrates his story in two parts. One focuses on Tony’s school years, beginning with his friendship with the enigmatic Adrian Finn, the new student at his all-boys boarding school. Adrian is cool, angsty, and smart; he reads Ted Hughes and comes from a broken home. He offers his teachers pseudo-intellectual justifications for not answering their questions (“I can’t know what it is that I don’t know. That’s philosophically self-evident”). Once at university, the second key character in Tony’s life appears: Veronica Ford, who, like Adrian, is alluringly inscrutable and elusive. Tony endures an awkward weekend at the Ford family’s home, including a steamy breakfast with Veronica’s sexually-charged mother. Before long Veronica dumps Tony and begins to date Adrian, a heart-stomping betrayal that threatens to confirm Tony’s misgivings about his own, prosaic nature.

The second part of Tony’s narration opens with a riddle. Veronica’s mother has now died, and has bequeathed the middle-aged Tony with Adrian’s diary. In both the film and novel the diary serves as the story’s hook: why did Mrs. Ford leave it to him? Why did she have it in the first place? And, what information does it contain about Adrian? These questions lead to greater thematic questions about memory and the consequences of seeing life through our own myopic worldview.

The film features some amazing British actors — Jim Broadbent as the older Tony, Harriet Walter as his ex-wife Margaret, Charlotte Rampling as present-day Veronica, Michelle Dockery as Tony’s daughter, and Emily Mortimer as Mrs. Ford. It seems like a missed opportunity not to use the engaging (and Oscar-winning) Broadbent to explore an unlikeable and narcissistic character. He instead plays Tony as one of your eccentric, luddite uncles. Rampling, at 71, remains electric, and manages to embody the person we imagine Veronica would become. But it is Harriet Walter as Margaret whose performance helps rescue the film––which makes it all the more ridiculous that hers is the only major character not featured on the promotional poster.

This is how the movie deals with explaining Tony’s past: Tony sits down with his ex-wife over pasta and wine and regales her with old stories. This scenario happens not once, but twice. Giving us a “plausible” reason for why Tony would be telling someone his backstory ends up feeling more artificial than if we were suddenly sucked into the vortex of the past. Walter, as his ex-wife, helps to mediate this stiff play-like format, in her subtle depiction of Margaret. Thanks to her we ultimately believe that these are two people with a complex past, divorced but still intimate. She can expose Tony’s bias without sounding like the plot device which, in these moments, she is.

A screenplay never contains every scene out of a book, nor does it follow its plot to the letter, and so it makes a certain kind of sense that the movie The Sense of an Ending combines the book’s two-part structure into one cohesive arc––this way the audience is intrigued by the mystery of the diary from the outset, and Tony’s “present” remains our fixed point in time. Still, I was stunned to find the essential character of Adrian practically cut from the film. This presents a problem from a technical point of view: without knowing much about Adrian, the story’s big twist––and it’s meant to be a doozy––doesn’t really make much sense. And yet, what bothered me more (likely because I had read the book, and unlike my co-moviegoer wasn’t left wondering what had just happened) was Batra’s choice to recast the novel as a conventional romance story about a boy and his first girlfriend. In the book it is his relationship with Adrian, not Veronica, that Tony mourns when he learns about the diary. Focusing on Tony’s romantic relationship with Veronica dismisses how important our platonic teenage relationships are, how much we invest in them, and how much they shape our identities.

The decision to minimize Adrian’s role in the film is all the more incomprehensible given the glut of other scenes he added (see: list above). In fact, the movie contains so much original material that it’s basically an entirely new story, that of the redemption of Tony Webster, a bumbling old man who receives a strange bequeathment which ultimately causes him to realize how selfish he’s been, especially with regards to his treatment of his ex-wife and his daughter. Here is one particularly telling sample of that extra material: in the novel Tony briefly mentions that his somewhat-estranged daughter is married with two children. In the film, the entire narrative arc is structured around his daughter’s fraught pregnancy; she is an unmarried 36-year-old who has chosen to have a baby sans father. Her baby’s delivery, with Tony standing at her shoulder as she pushes — literally and finally “there” for his daughter — is one of the film’s emotional highs. But why take a novel already stuffed with emotional stakes — two suicides, multiple broken hearts, forty-year secrets, unwanted babies, festering regrets––and add to it this new plot device?

I can only point to the text, to the sentences themselves. Julian Barnes is easy to read; his language is straightforward and unfussy. He doesn’t load up on adjectives or run sentences on for pages to mirror his character’s emotions. Perhaps the absence of dark, taut, or twisted language misled the movie team, and they read Tony as a conventional old British man (the way he invites the mailman in for coffee in the film certainly suggests this). Barnes excels at subtlety; his Tony’s regrets are slow burning, shrouded in fake candor. Or maybe Hollywood simply doesn’t accept unhappy endings.

Because the novel isn’t happy. Its ending does not uplift the reader, as the final lines suggest: “There is accumulation. There is responsibility. And beyond that, there is unrest. There is great unrest.” Yes, there is a revelation––Tony realizes he has deluded himself about his life, that he’s been indulgent and simply told himself the version of history which made him feel better about himself. This kind of a realization is a personal triumph, but sometimes, maybe oftentimes, it’s a small one, fruitless except for the inherent goodness of realizing the truth. That’s why Tony never actually reads the diary he receives — it’s moot, he can no longer change how he behaved towards Adrian or Veronica; there can be no satisfactory end to their story. There can just be an end.

The Jittery Fearful Tone of Julian Barnes’ The Noise of Time