Novel Gazing

The Skeletons Tangled Under Our Feet

Reading Paul Monette’s AIDS memoir helped me figure out how to move forward after my boyfriend’s death

Novel Gazing is Electric Literature’s personal essay series about the way reading shapes our lives. This time, we asked: What’s a book that almost killed you?

Paul Monette’s final resting place is in Forest Lawn, a cemetery in the Hollywood Hills, beside the plot of his longtime partner, Roger. Just above their graves, completing a posthumous love triangle, lay the remains of Roger’s romantic successor Steve, the second companion Monette lost to AIDS in a handful of years.

I’ve never found cemeteries all that spiritual: the forced solemnity and clumpy grass are the opposite of transcendence. But there’s something resonant about Forest Lawn. Every day at a Southern California cemetery is the perfect day to visit, cheery skies and wise old trees to lean up against. It’s why tourists like me come to stargaze.

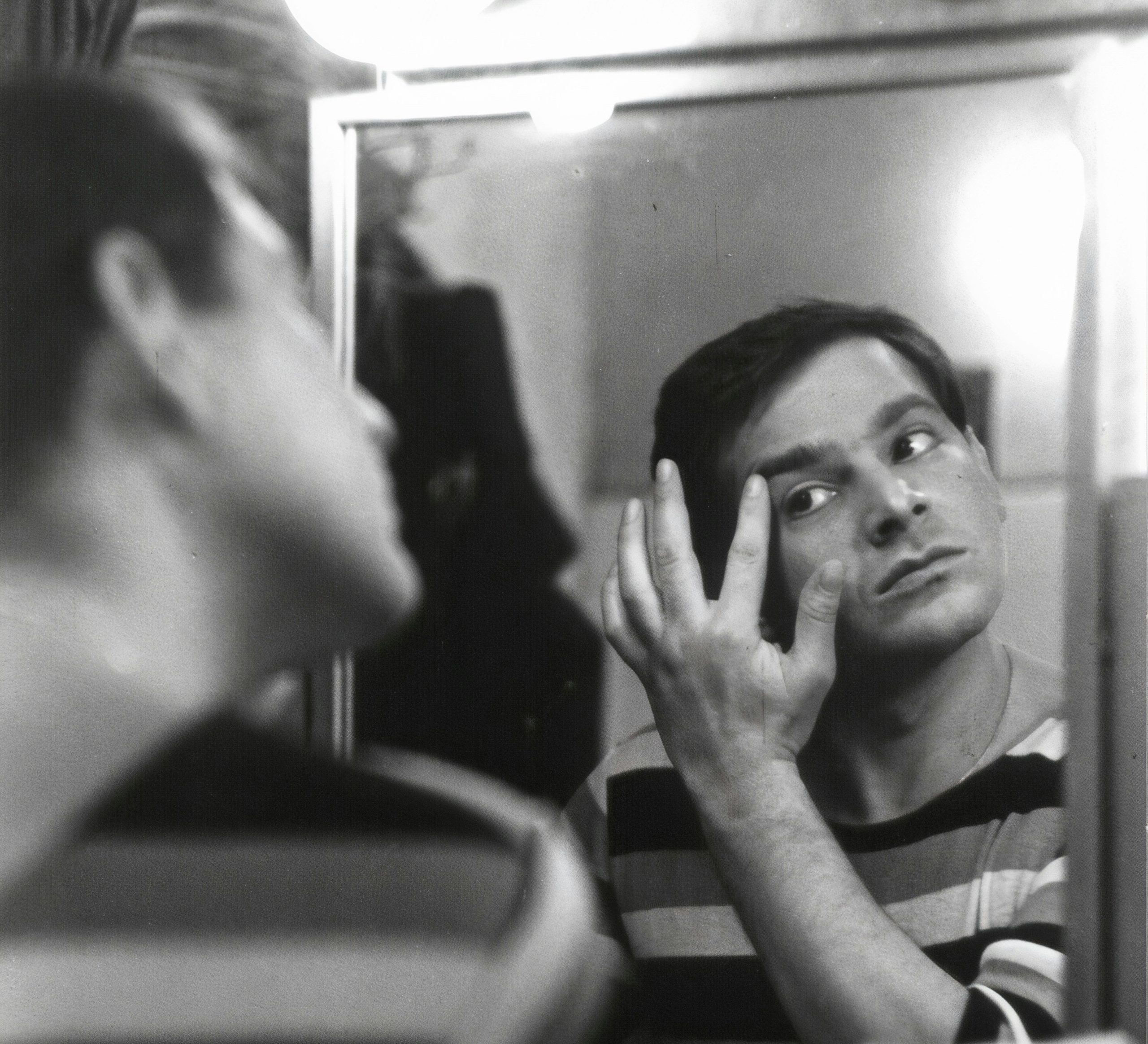

I made the pilgrimage to Monette’s grave in December 2011, a little more than a year after losing Corey, my first real boyfriend, to pneumocystis pneumonia. Corey had lied to me about getting tested for HIV and lied about being negative. At the time of his death, at the age of 25, he had what his little brother described to me over the phone as “full-blown AIDS” and a T-cell count of 22. Corey’s symptoms over the eight months I’d known him — weight loss, a nasty cough, a lesion I’d mistaken for a birthmark — seemed ominous only in retrospect, but according to his brother doctors said Corey’s body was so ravaged by the time his mom drove him to the ER that October morning he’d probably been battling the virus for seven years without treatment.

I made the pilgrimage to Paul Monette’s grave a little more than a year after losing Corey, my first real boyfriend, to pneumocystis pneumonia.

I was blindsided. Two months before his death, Corey, then seemingly happy and healthy, had helped me move from Los Angeles to Austin, where I was starting graduate school on a fellowship thanks to the largesse of the epic historical novelist James Michener. The ongoing joke at the Michener Center that fall, at least according to one especially witty poet, was that we’d each be responsible for completing one of James Michener’s great unfinished works — one per semester, in fact. Michener had completed Hawaii, Alaska and Texas in his lifetime. The other 47 states were up to us. “I’ll take Nebraska!” someone would say around the workshop table. Someone else would reply, “Great, because I’ve got dibs on Oklahoma!” It’s a schtick I still find charming as my first semester in the program, my mom gift-wrapped our family’s hardback copy of the Michener tome Space and mailed it to me for my birthday.

Corey got me settled in this new city with its bats and cockroaches and terrifying frontage roads. We bought a TV at Costco, swam in Barton Springs, made love on a mattress on the floor of my unfurnished living room and watched Dirty Harry and Once Upon a Time in the West. After ten days, I bought him an orange Longhorns baseball cap as a thank you and dropped him off at the airport. We weren’t what you’d call a couple, but we Skyped all the time and were planning on spending New Year’s Eve together. I knew he’d look hot in a tux.

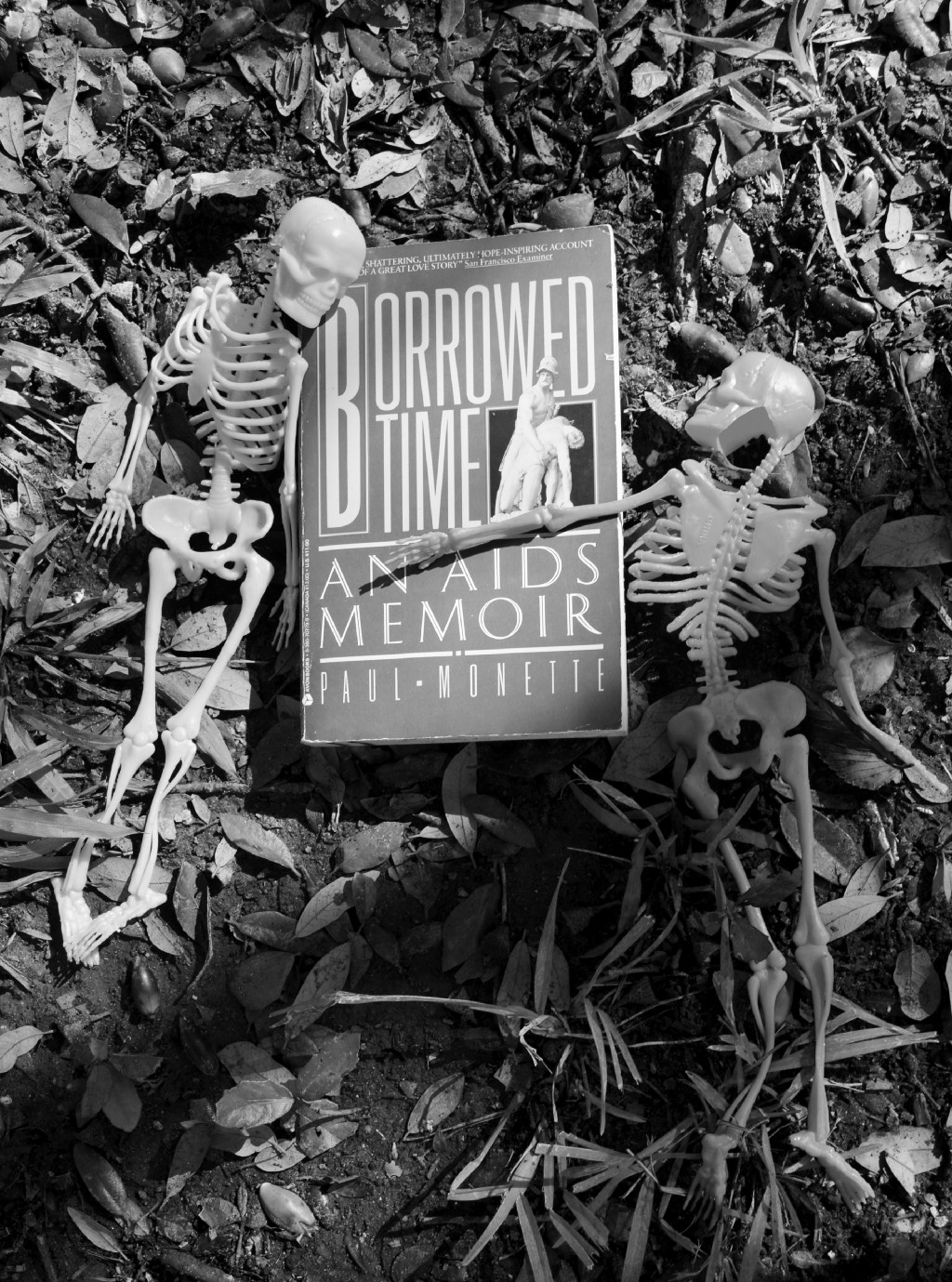

Instead, I passed Christmas break that year in shock in my childhood bedroom in Salt Lake, sobbing over Monette’s Borrowed Time, a harrowing account of Roger’s nineteen-month battle with AIDS.

The white stone and green grass of Forest Lawn are as corporately beautiful as the JW Marriott in Palm Desert where my family used to vacation when I was a kid. The grounds boast fountains and neoclassical architecture and the kinds of winding roads and spectacular views we’ve seen a thousand times in movies, usually set to bagpipe music.

It may be the fact that Forest Lawn is so spectacular, so idyllic, so country club that makes it start to feel haunted. Your eyes get bored. You start to look past the Xanax-ed prettiness of the place, to suspect the prettiness. We’re all a little goth in cemeteries. “Certainly, this can’t be it,” you think. “Can death really be nothing more than a golf course?”

‘Certainly, this can’t be it,’ you think. ‘Can death really be nothing more than a golf course?’

Finding Monette’s grave required GPS coordinates, helpfully available on his Wikipedia page, which my friend Katie pulled up for me on her iPhone. Still, we stumbled upon the final resting places of Walt Disney and a dozen other celebrities trying to find it. It’s just a marker in the ground, not covered in flowers or housed in the grand mausoleum, like Michael Jackson’s remains. Nor is it the gaudy, autographed white marble of Liberace’s tomb, though once you spot it there’s no mistaking it for any other. Under Monette’s name, the grave unapologetically reads “CHAMPION OF HIS PEOPLE.”

The setting is idyllic, dappled in the shade of a California live oak on a hill, though it was the ashes and skeletons underneath that I was thinking about.

In Monette’s final book, an essay collection called Last Watch of the Night, published in 1994, a few months before his death at the age of 49, Monette describes visiting these plots at Forest Lawn to bury Steve. Standing over his own future gravesite, Monette imagines Roger and himself as a pair of skeletons “tangled together like metaphysical lovers out of Donne.” He goes on to picture one of his “bone-white arms reaching above my skull, clawing the dirt with piano-key fingers, trying to get to Steve’s ashes, just out of reach.”

For all its lyricism, dark humor and beauty, Borrowed Time has a fairly traditional riches-to-rags structure: it tells the story of how Paul and Roger met and fell in love, and how they lived a bougie, glamour-adjacent life in Los Angeles: Paul drives with the top down and writes novelizations for blockbusters like Predator; Roger is a successful lawyer. Paul was educated at Yale, Roger at Harvard. In the early ’80s, AIDS starts picking off their friends. Roger falls ill. Then Paul does. The epidemic ends up costing them everything: the sporty car, the easy money, even Roger’s eyesight. Everything, that is, except each other’s devotion.

The New York Times review of Borrowed Time, published in 1988, aptly describes Monette not as an AIDS prophet or an angel of death but as a war correspondent. The first sentence of the book reads, “I don’t know if I will live to finish this.” Three hundred and forty-one pages later, Monette has not only finished his memoir, he has managed to write one of the most moving love stories of his time, and done so on a mortal deadline.

Borrowed Time is a test of writerly endurance, an unsparing account of Roger’s painstaking decline written with such command and grace that in a different world high schoolers would know Paul and Roger as thoroughly as they know Romeo and Juliet.

In a different world high schoolers would know Paul and Roger as thoroughly as they know Romeo and Juliet.

The book is also the story of one of the most gifted writers of his generation finding his voice and subject. It was only after Roger’s death in 1985 that Monette devoted himself exclusively to chronicling the human toll of the epidemic, famously saying that AIDS was the only thing worth writing about.

Normally, I’m attracted to big-hearted, bright voices like Elizabeth McCracken, David Mitchell, and George Saunders, but Monette’s style is epic in another way. It’s almost Homeric: classical, starchy, riddled with allusions to the Greeks, as reportorial and unflinching as anything in The Iliad. Early in Borrowed Time, Monette writes about feeling “confirmed” by the idea of the Ancient Greeks even as he acknowledges that he’s being hopelessly romantic about a civilization that treated women like garbage and enslaved folks to build its palaces. A gay man, he says, “seeks his history in mythic fragments and jigsaws the rest together with his heart.”

I love Paul Monette’s prose in the same way I love a crumbling Greek statue that’s lost an arm, part of a leg, maybe had its nose snapped off, but is somehow still sporting an archaic smile. Monette writes like William F. Buckley’s queer, not-evil twin, not like he’s nibbling a canapé at the Yale Club but like he’s marshaling the full weight of his privilege, intelligence, and pedigree to prosecute the case against the world’s indifference to AIDS.

I didn’t read Monette that Christmas for closure, as a saner 26-year-old might have — one who wasn’t in a writing program, say; one who wasn’t also in search of his voice and subject. Monette offered me not closure but confirmation, confirmation that it was worth risking your heart on every page if that’s what it took to tell your story.

Corey’s funeral announcement that fall had consisted of 39 words on a newspaper website — fewer words, I’d find out later, than the inscription on Paul Monette’s grave. There was no mention of what had killed Corey, just that he was a beloved son, grandson, and brother and that he’d be missed — all of which was true, but come on. After all, it was shame and secrecy that killed him in the first place. I was ready to let in some light.

Monette offered me not closure but confirmation, confirmation that it was worth risking your heart on every page if that’s what it took.

This business of letting in light sounds a little grand, I know. After all, I’m alive to open a window and feel the sun hit my face and Corey isn’t. And I’m not talking about getting tested or keeping in touch with Corey’s little brother over what has, impossibly, become eight years since his death. All of that just sort of happened. I hate to admit it, but what I’m getting at is a little grand: I didn’t want to forget him. I wanted to tell people about Corey and me, and not just his senseless end but the dumb, fun parts of our relationship, too. “You can just be done,” one friend told me, but I knew I wasn’t.

The risk of talking about the dead is that we romanticize them. On the other hand, what’s wrong with a little romance? Let me remember watching a Clint Eastwood movie on a mattress on the floor of my unfurnished living room with the only other person I knew in this entire city lying next to me, his arm going to sleep under the weight of my neck.

Borrowed Time is romantic in the way that Grimms’ Fairy Tales are romantic. The memoir is a love letter as sharp and true as an arrow, one that draws blood. I read it with a pit in my stomach and realized only later why: I was jealous. Monette had not only written about the passion between two men in the face of an epidemic, he and Paul had lived it. Corey and I had every advantage — two decades of medical advances, ACT UP protests, movies, novels, televised fundraisers — and none of it had saved or even prolonged Corey’s life. We weren’t Paul and Roger 2.0. Corey hadn’t even trusted me enough to tell me he was sick. That’s the part that almost killed me.

There’s something scary about reading the exact right book at the exact right moment. I remember feeling about Borrowed Time the same way I’d felt when my dad and I took up Cormac McCarthy’s The Road together the summer after he’d been diagnosed with ALS. When I’d asked Dad if he was liking the book, maybe a dumb question considering it’s about the apocalypse, he’d said matter-of-factly, “This is our life right now.”

The risk of talking about the dead is that we romanticize them. On the other hand, what’s wrong with a little romance?

Dad’s fingers weren’t working anymore and I remember him sitting at the kitchen table, pinning the book down with one curled hand and turning page after page with his knuckles. Dad had been a newspaper publisher. Though his job was more on the business side of things, I knew he valued writing. I’d come across a line or two in a notebook of his when we were packing up his office. I don’t remember what the lines were, only that there were unmistakably the start of a book about his life he was never going to complete. It was already too late. He couldn’t even peck out an email.

I had a journalism degree so new the actual diploma hadn’t yet arrived in the mail and a habit of writing poems under the gazebo at night with my friends, but it was only hanging out with Dad that summer that I had the conscious thought that I wanted to be a writer so when the next bad thing happened, I’d be ready. I didn’t have to be Picasso doodling a masterpiece on a bar napkin. I just wanted to have something to say when shit hit the fan.

About a year after Dad died, a friend of mine who had already lost both her parents said to me, “At least you’ll never run out of material now.” I remember being taken aback, but the statement has turned out to be true time and time again. Another way of saying it might have been, “Your dad is dead and you’ll never get over it. You’ll lose other people, too. You can write or you can die.”

Your dad is dead and you’ll never get over it. You’ll lose other people, too. You can write or you can die.

Monette said writing kept him alive. Indeed, his words feel snatched from the grave. “He kept writing until the end,” the Times noted in his obituary, this in spite of Monette being hooked up to an IV and taking heavy duty meds while completing Last Watch of the Night. Monette’s final years were easily the most prolific of his career. They included the publication of two novels and a second memoir, Becoming a Man: Half A Life Story, which won the National Book Award in 1992. It remains Monette’s most popular work. But it’s Borrowed Time I return to again and again. It’s Borrowed Time that sent me to the cemetery.

I wasn’t sure what to do once we actually found the grave. If I’d thought ahead, I would have brought flowers or even a card. As it was, I just sat in the grass next to Monette and had Katie take a picture of us, and then I got up, brushed off my jeans and went blinking back down the hill. That’s the thing about books that almost kill you. They’re the ones that end up saving your life.