interviews

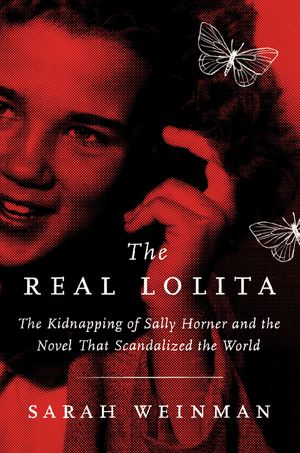

The True Story of the Real Lolita

Sarah Weinman on the kidnapping of Sally Horner that inspired Vladimir Nabokov’s novel

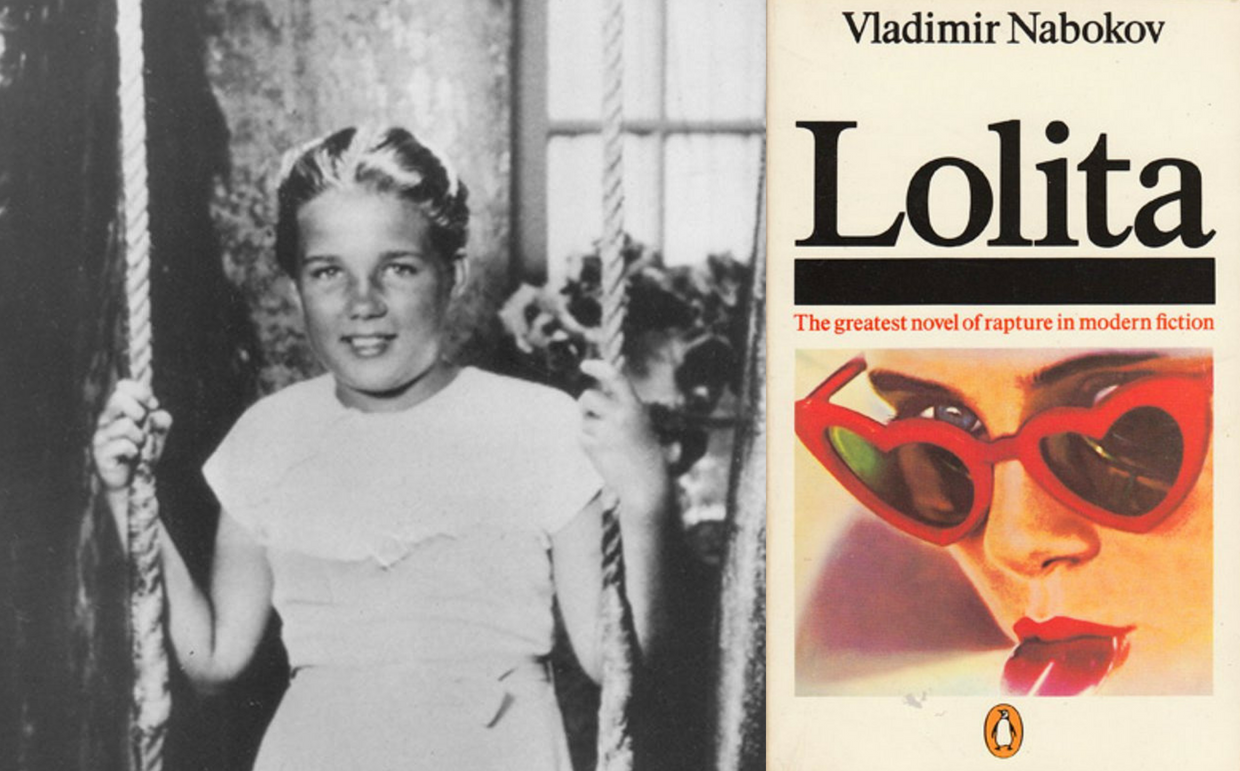

Sally Horner was 11 years old when she was caught stealing a notebook from a corner store in her hometown of Camden, New Jersey, by a man named Frank La Salle, who claimed to be an FBI agent. La Salle said that Sally could avoid being sent to a reform school (or worse) only by staying in his good graces, a threat which turned into a 21-month ordeal of kidnapping and rape as the two drove across the country posing as a father and daughter.

Sarah Weinman’s The Real Lolita considers the real-life kidnapping of Sally Horner as a direct influence on Nabokov’s famous novel of obsessive romance and sexual abuse. Although Sally is mentioned by name in Lolita, Nabokov never acknowledged her case as having any serious bearing on the book, and The Real Lolita makes a compelling argument that this demurral is both specious and, in many ways, tragic.

By coincidence, I published a novel in June 2018 called Invitation to a Bonfire, inspired by Nabokov’s marriage to his wife, Véra, and the complicated power dynamic that existed between them as he rose to become a literary star. As a Nabokov fan and a true-crime obsessive, I was primed to admire The Real Lolita which explores the Nabokov marriage from a related angle, honing in on Vladimir and Véra’s collaboration over the writer’s image. When Weinman’s book crossed my radar, it felt like fate — as if we were already in conversation, without ever having met.

Adrienne Celt: I was intrigued to learn you did graduate work in forensic science before becoming a full-time writer. For those of us who view that discipline through rosy, Dana-Scully-colored glasses, can you talk about what led you down that path, and whether you considered pursuing forensic science as a career? How does it influence your journalism today?

Sarah Weinman: It’s funny, I recently finished working on a feature talking to forensic science experts about the ongoing true crime boom and whether it’s a boon or a hindrance to their work, and it’s been a massive excuse to reconnect with my old graduate school professors, instructors, and classmates. I grew up splitting my time between science at school and music in extracurricular — my older brother was the “writer in the family”, not me — and when I was finishing up undergrad at McGill University, where I majored in biology, I stumbled onto the website for John Jay College’s forensic science program and had that light bulb moment of, “holy shit, there’s a program for this? I can combine my love of crime and science as a profession?” So I applied, got in, moved to New York, the city of my heart always, in August 2001, and with the exception of a two-year stint back in my hometown, have been here ever since.

‘The Real Lolita’ is my version of Sally Horner’s kidnapping, rescue, and tragic demise. But the only one who could really tell her story fully and properly is Sally herself.

I did consider pursuing forensic science as a career. But I realized (though it took me a while and several failed job interviews) that I was more of a macro thinker in a micro world. Forensic biology in particular, but really so many of the fields, are about the day-to-day of laboratory work. And I wasn’t good at it. I wanted to look at real crimes and cases (and, well, drink with crime writers at book events & conventions). I wanted to understand what makes ordinary people snap or why psychopaths kill people for sport. Crime is society, the world, life. And I wanted to understand it all, through reading and writing both fiction and eventually, journalism.

Though the vast majority of my feature stories don’t involve forensic science, what I learned in grad school was indispensable to doing this journalism. Being curious, a natural skeptic, looking for evidence. But it’s also counter to journalism, which prides itself on creating narrative. Science gives you facts even if they don’t fit into a tidy box, much as we desire that they do.

AC: I can see the difficulty of being a macro thinker in a micro world; it’s very clear in The Real Lolita how your work benefits from room to breathe. The story raises questions not just about incident, but ethics, ambition, art, and the murky origins of inspiration. Which leads me to my next question.

You point out a number of times in the book that Nabokov had a lifelong interest in writing about obsessive relationships with prepubescent girls — though you’re careful to categorize it as an aesthetic interest, not a deviant one. Still, that compulsion was clearly important to you as a writer, and I’d love to hear more about how this motivated your work.

SW: Just to be clear here: you mean that it was important to me that I trace the literary progression of Nabokov’s own compulsion?

AC: I do!

SW: Then yes, I felt like I had to spell it out in a way that showed there was a pattern, an unscratchable itch, the main “thing” that he so often wrestled with in fiction in different ways, with varying success or failure, until he finally arrived at Lolita. Part of it was to show the aesthetic aspect, or even the craft part: that authors have a root theme they come back to repeatedly, but not necessarily successfully. The paragraph in The Gift is a clear precursor to Lolita but it isn’t written as well or obviously developed with the same brilliance. Same as The Enchanter, where the bare bones of Lolita are present, but dressed in a way that doesn’t quite work — and Nabokov knew it, otherwise he would have published it during his lifetime (though I am glad it appeared posthumously).

But compulsion as a basis for fiction fascinates me in general, because I believe readers know when a writer is acting from some more primal instinct, no matter how brilliant they are at conveying the complexities of that compulsion. Whether or not Nabokov was acting from some sense of cloaked moral outrage or something more sinister, or something in between, is not knowable, at least based on his archives, his history, his experience. Though I do tend to think it’s the former (and Véra’s diary note about it lends further credence) but since he was all about art for art’s sake, he wasn’t about to admit it!

Also I wanted to ask you a question, Adrienne: did you have a sense, while writing Invitation to a Bonfire, that you were up against the Nabokovian ghosts? I sometimes felt like I was going to be haunted by Vladimir, and especially Véra, for publishing The Real Lolita, but of course it wasn’t about to stop me from writing the book. But VN, that dynamic duo with the same initials, is such a daunting specter — and yet I also feel like the most successful writers to grapple with that specter are women. Not only you, but also Roberta Smoodin with Inventing Ivanov(have you read that novel? It’s so wonderful.)

AC: I love that the compulsion itself is such a driver for you — in a sense, you’ve made Nabokov’s aesthetic obsession into a narrative engine for your story, which is a beautiful and very literary form of cannibalism. (I hope it’s clear I mean that as a compliment.)

In answer to your question: I wrote the first two drafts of Invitation to a Bonfire completely privately — didn’t tell anyone about them, didn’t talk about the story — and I think that helped me largely escape the agony of influence. The only person I was really in conversation with during the process was Nabokov himself (and, of course, Véra), but I think I was talking to my personal Nabokov, the one who is so intimate and familiar to me from reading, rather than the real man. Which allowed me to insert my own sense of authorial control into the process, in place of his — which would likely have been more forbidding. (Also, no, I haven’t yet read Inventing Ivanov, but I very much want to!)

It was fascinating for me to dive into The Real Lolita after working on Invitation, because despite taking inspiration from the power dynamics of the VN/VN marriage, I actually avoided doing research while I was writing, to give myself and my (imaginary) characters a bit more free reign. Your work is so richly researched and meticulous with the truth; I felt like there was an inspirational kinship between the books, if a differently refracted one. So I’m interested to hear what your intellectual process was with The Real Lolita: did you come to it with a solid hypothesis (“Sally Horner was definitely the inspiration for Lolita” for instance, and/or “Nabokov was hiding something”) or did you start with a question?

SW: First I have to single out this idea of “talking to my personal Nabokov” because I think it has to be that — dealing with specters, avatars, biographical representations, but the only person who could truly understand Nabokov was Nabokov — even Véra couldn’t have had access to every personal and intellectual part of it. (If she had, what of poor Irina Guadinini?) And I think it was wise you knew enough to have the seed of your novel, but not too much to let reality seep in.

As for my intellectual process: I started with the parenthetical in Lolita: “Had I done to Dolly what Frank Lasalle [sic], a fifty-year-old mechanic, did to eleven year-old Sally Horner in 1948”? That line blinks like the most garish neon sign, waiting for someone to notice. And while it turned out (as I discovered while I wrote the book) that someone else had noticed, as far back as 1963 — a young jazz writer named Pete Welding, later a record producer of note — it was Alexander Dolinin’s 2005 essay for TLS that made the connection between Sally’s kidnapping and Lolita more, well, explicit.

I figured Nabokov was far too smart to map Lolita exactly to Sally’s plight. He had this compulsion and it was bigger than any one girl, any one case. But I also figured that he knew of Sally Horner before reading of her car accident death in 1952, but didn’t want to make that too obvious, lest prying eyes like Pete Welding ask him about it. (Once Welding, and the NY Post reporter, Al Levin, who read Welding’s piece, got the brush-off by letter from Véra, no one asked for decades!) The clues are there, though the case for how much Nabokov knew about Sally is ultimately a circumstantial one. I would have loved to slam-dunk it beyond the notecard in Nabokov’s archives at the Library of Congress, but I think a part of me would have been disappointed in VN if I had? I peeked plenty behind the curtain, so to speak, but I appreciate there’s enough of a veil left over that keeps him at an opaque distance from my prying eyes.

AC: Let’s talk about Sally Horner. Were you ever tempted to write a more straightforward true crime book about her, and leave Nabokov as more of a footnote? The inspiration you mentioned above suggests not, but I’m curious how you balanced your desire to give Sally’s story a voice with the need to let that story stay entangled in Nabokov’s messy, private set of influences (and his ambition).

SW: I was never tempted, no. Because The Real Lolita grew out of the article I wrote for Hazlitt — also “The Real Lolita”, though while I was writing the book I had a different working title, Among The Wholesome Children, which I think of as the book’s shadow title still! — and the entire point of that piece was to write about “the real life case that inspired Lolita,” so I always thought of Sally’s plight in conversation with the novel. That said, it was crucial that Sally’s voice take prominence, because her voice was erased. I wanted to know what happened to her. I still feel such a sense of tragedy that her life was cut short too soon, that she did not have the chance to grow up. That, in some alternate universe, she would have read a book like Lolita and responded to it, because Sally, as friends and relatives told me, was quite bookish, the type of girl to read contemporary literature of the day (I still wonder if she read The Catcher in the Rye, and if so, what she thought of it!)

Balancing Sally’s story with the Nabokovian influence was not easy, though. I always knew Sally was the book’s spine, and the road trip helped tremendously with the structure. But getting the Nabokov sections to fit, like spokes, took a long time, and several rounds of edits. Once I realized that mirroring where Nabokov was at a particular point in his life to where Sally was in her cross-country nightmare was the best way to go, The Real Lolita did start to come together more fully.

AC: The symmetry really works. But that’s the challenge of non-fiction, isn’t it? To structure a compelling story while faithfully adhering to facts. Interestingly, we live in a time when many writers — Rachel Cusk and Karl Ove Knaussgard, for example — are having their cake and eating it too in this regard, publishing work that takes direct influence from their lives but calling it fiction, and therefore reserving the right to shape it however the story requires. Autofiction is so much at the vanguard of contemporary literature; do you think, in this environment, Nabokov may have been inclined to loosen up a bit, and more freely acknowledge his influences?

SW: What a great question. I suspect he would have, but under serious duress! Though there is a larger consideration of whether Lolita could be published in our current climate, considering all of the recent bad-faith efforts to intuit literal meaning in what are clearly obvious, if tasteless, jokes. And while I hope the answer is still yes, because even after all these years of working on the book I do believe Lolita holds up as brilliant art, some of the parallels between 60 years ago and today are pretty spooky! Mostly in terms of publishers who didn’t have the nerve to be the ones on the hook, legally, if they needed to defend Nabokov or Lolita in court. Do you think Lolita could be published today?

AC: I’m honestly not sure! I do think that our tendency towards moral panic today is different than the American attitudes towards sex (both sensationalist and Puritan) that made it difficult for Nabokov to publish Lolita in his time. Today we’re more focused on callout culture as it relates to one’s private life; so it’s possible that the book would actually face less scrutiny from publishers now, unless there was a plausible accusation to be made against Nabokov the man. (Which, who knows.) I mean, Alissa Nutting’s Tampa was published in the past few years; Amber Tamblyn’s new novel is about sexual violence. I don’t think there’s as much sense these days that a book about prurience will cause prurience, though I grant that both those examples are imperfect analogues, since they’re written by women (which I think makes them easier for a certain part of the culture to accept).

I do wonder if there would be a less voluptuous reception to the novel once it did come out. I mean, can you imagine a Lolita musical being produced today? (Or, for the sake of a clearer parallel: a Tampa musical?)

SW: I’m also thinking of John Colapinto’s most recent novel, Undone, which was consciously trying to update Lolita for the 21st century — and it was turned down by all manner of US publishers, only finding one after being published in Canada, and ultimately did not sell all that well. On the one hand, no one tried to intuit that Colapinto himself was his narrator; on the other, the appetite for reading such a book by a white man was, shall we say, muted? And would likely be even more so post-#MeToo?

Many misread the novel as a love story because the truth is so hard to digest.

Of course, Lolita was the first, and still the best (I love Tampa; I haven’t read Amber Tamblyn’s novel yet, though.) And because the novel is so genius, so singular, no wonder it’s had a hell of a time being adapted into other media, no matter the attempts. I’ve spent the past few weeks looking more deeply at the ill-fated Lolita musical, because I am amazed so many people who should have known better thought it could be a viable Broadway musical. I am amazed Edward Albee thought he could adapt Lolita into a Broadway play (it flopped, of course.) The two films tried, but Kubrick ran into censorship trouble and Adrian Lyne did too, after a fashion. My brother, also a writer, told me his theory of why Lolita is so hard to adapt: because when you strip away Nabokov’s dazzling prose and manipulative obfuscation, what you are left with is a character, in Humbert Humbert, who is a crashing bore. And seeing Dolores Haze on screen is a queasy experience.

No wonder so many who read the novel really misread it as a love story. The truth is so hard to digest, which is why putting Sally Horner at the forefront forces us to reckon with this most unpleasant of truths, the repeated rape of a child.

AC: Yes, Humbert Humbert’s power lies in his ability to charm readers directly; on screen, you can only see him charming other people, and it doesn’t work as well. He has to be able to seduce you, because otherwise you see right away that he’s seducing a child.

I wonder if you could speak to the effort writers are asked to put into cultivating a public persona. It feels gauche and sort of gross to admit to having any sort of personal “brand,” but in a year when you have a book out, you become very aware that the public is going to develop a story about you — and you can either participate in that story, or just let it happen to you. I find myself wondering if I tilt towards being too available; whether it allows people to cherry-pick elements of my personality (for example, being young, being female, being social) that validate a subconscious desire to consider my work less seriously. Nabokov clearly tilted hard towards controlling his personal narrative, and in many ways it worked — but arguable at the cost of Sally Horner’s legacy, among other things.

How do you think about this for yourself? Is there less call for it in journalism and non-fiction, where the text itself at least appears to give readers the authentic access they crave? Or you feel there’s a moral imperative to outline what “kind” of writer you are (sincere, gonzo, distant, emotive, etc.) when other people’s stories are at stake?

SW: Ah, see, I have come to realize, after all these years of doing journalism and criticism and feature writing and publishing reporting, that I am actually a pretty good marketer. I joked to my publisher that I was less concerned with reading reviews on Goodreads and Amazon than I was about making sure the metadata was on the level and that the search engine optimization was 100 percent sound (you may surmise I am a geek, and this is correct.) So by virtue of the niches I’ve occupied — editing anthologies of women crime writers of the mid-20th century, then true crime at the intersection of culture, also usually 20th century — that adds up to a pretty tangible brand. My newsletter’s called The Crime Lady for a reason: it’s the simplest, pithiest phrase to describe what I do all day, and what I plan to do all day for the rest of my working life.

So maybe that’s another way I admire the Nabokovian desire for utter authorial control. I’d also rather people respond to my work, and not to me personally. It’s only recently that I’ve felt confident enough to venture into personal essay territory. I never felt I was much good at it before and hid behind writing about other people. But when it’s done well, the personal essay is one of the most rewarding genres of writing. I just finished Anne Boyer’s new collection, A Handbook of Disappointed Fate, and that sparked my mind in ways I’m still contending with. So too do hybrid-y writers like Maggie Nelson or Nathalie Leger (everybody has to read Suite For Barbara Loden!) or, from earlier decades, Theresa Hak-Kyung Cha or Elizabeth Smart or Elizabeth MacNeill aka Ingeborg Day. I love writers who engage me on every possible level. But I also love a damn good yarn, too.

AC: Finally, I know you talked to Sally’s surviving relatives as part of your research, and I’m curious if you’ve reached out to them again — or plan to — now that it’s finished. Have they read the book?

SW: I’ve stayed in contact with Diana, Sally’s niece, yes. (I spoke with her father, Al Panaro, for the original Hazlitt article, but he passed away in 2016. There may be other relatives who emerge, but I didn’t find them!) She hasn’t read the book as of this writing, but I suspect she may have by the time The Real Lolita publishes. There’s no hard and fast rule about how long to stay in touch with sources after an article or a book publishes — I’ve talked to fellow journalists about this, some do, some do not — but it felt important for me to keep Diana apprised of some of the major publishing developments, since Sally Horner will belong to the world in a bigger, more archetypal way than ever before. But for Diana, Sally was family, the aunt she barely knew (because she died when Diana was only 4 years old), memories informed by photographs and film clips a whole lot more than the actual person. And if I lose track of that, and also a sense of care and duty, I’ll feel like I did a real disservice to everyone.

Obviously, The Real Lolita is my version of Sally Horner’s kidnapping, rescue, and tragic demise. Other people could have, and do, put together their own versions. But the only one who could really tell her story fully and properly is Sally herself. Since she cannot, and never got a chance to, I hope I did the best I could, and that Sally remains in our cultural consciousness from now on, and for good.