essays

The Video Game That Shows Us What the E-Book Could Have Been

How ‘Device 6’ illuminates the past, present, and alternate future of the book

By now, we’re all used to the idea that books don’t have to be physical objects of ink and paper — but with only a few exceptions, our digital books behave almost exactly like our old-school ones. Yes, you can change the print size of an e-book, or look up a word instantaneously, but on the whole, reading a digital book is effectively the same experience as reading a physical book in a slim plastic shell. Our e-books are almost always electronic versions of our print books, and our e-book readers are often designed to mimic the print book experience as closely as possible. I love my Kindle, but it doesn’t really feel like a quantum leap over the shelves and shelves of printed books that I still own and read.

After all, it isn’t meant to. A printed book is one of the first technologies many children learn how to use, but it’s still a technology, and once we’ve mastered it most of us don’t appreciate being asked to figure out how to read all over again. This one of the reasons why books that experiment with form, whether digital or print, tend to sell rather poorly. No matter how radical the content, we are conservative about the structure of our reading.

For a vision of a more daring alternate future for digital reading, though, we can look instead at a game. Device 6, a 2013 mobile/tablet game by Swedish developers Simon Flesser and Magnus Gardebäck, lets the reader encounter and explore text in a format unfettered by the demands of the printed book, giving us a peek at what the rewards of pushing text a bit further in the digital era could be.

As a story, Device 6 reads like W. G. Sebald writing an episode of The Prisoner. As a game, it plays like a version of the 1993 CD-ROM classic Myst pared back to its essentials. (In Myst, you spend your time exploring parallel universes at the behest of two mad brothers who are trapped inside books; in Device 6, you’re exploring inside the book yourself.) But as a book, Device 6 is something altogether new: a vision of what the printed word could be when set free from the prison of a static page. And Device 6 doesn’t just gesture towards an imagined lost future of digital reading — it’s also a commentary on what books mean in the present. It brings us face to face with the reality that every book, printed or digital, is not just a record of language or the conveyance of an idea but a construction of a particular space.

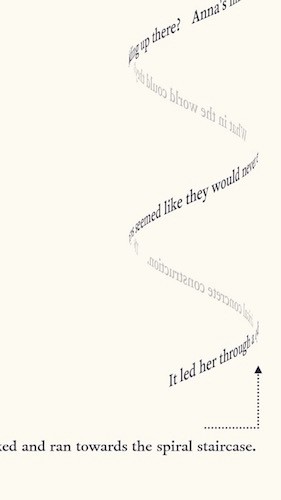

Like most electronic text (though not, interestingly, like e-books), Device 6 invokes not the codex book but the scroll: it features a single extended written surface rather than a series of discrete pages. While readers who spend a great deal of time online will find this immediately familiar, it’s also a canny physicalization of the story’s action. The protagonist, Anna, inexplicably awakens in a mysterious mansion and must explore its rooms and halls, a journey that the reader experiences through scrolling text that labors to mimic the mansion’s sprawling layout. That is, when Anna turns a corner, so does the text.

As Anna’s paths lead her back and forth within the mansion, the words of the story itself reflect her varied motions.

This can, in a still image, become a bit complicated.

In motion, however, this multiplicity of direction is much more intuitive. In the image above, the reader can follow the arrow and scroll the story to the left (well, the right, as I imagine most readers would, like me, rotate the screen rather than trying to read upside-down), or she can instead imagine herself turning into a different hallway and scroll the text down instead.

But while the experience of reading Device 6 resembles unrolling a parchment scroll and discovering foldouts pasted into the main body of the text, leading in unexpected directions, Device 6 is not in fact a parchment scroll, and whether it can be considered a book depends a great deal on how far one is willing to stretch that particular category. I’m not sure Device 6 should be properly described merely as a “video game” — in part because of the stigma that label can carry, and in part because I’d like to try to break down the walls we tend to build in our media consumption and consideration. (We all know that we “play” games and “watch” films and “read” books and “listen” to music, and that conventional wisdom tends to let boundary-breaking media, like games you read, fall through the cracks.) But at least part of what makes Device 6 work is its very gaminess.

The experience of discovery and revelation, described in the text, is reinforced by being enacted by the reader.

While Device 6’s story is primarily textual, and the movement through its spaces is guided and shaped by its manipulations of that text, it also requires the reader to solve a number of puzzles to open new spaces, and these puzzles largely play out through sounds and images. Like Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, Device 6 places black-and-white images among chunks of text to help build its eccentric imaginative world — but freed from the permeance of the printed page, the images in Device 6 shift and change. These dynamic visual and aural elements, as well as Device 6’s textual direction and manipulation, are made possible by the specific code-driven environment of a mobile app executed on a mobile device. And the experience of discovery and revelation, described in the text, is reinforced by being enacted by the reader.

At one point, Anna dons an electronic mask to make an invisible bridge visible through words.

Of course, neither that sentence nor even an animated gif can really capture the experience of discovering the invisible bridge. Following the text from left to right, the reader discovers the electronic mask after unwittingly passing the location of the bridge. When she puts it on, the visual landscape changes immediately, like looking through a sheet of red transparent plastic, but the reader must discover the extent of that change — including the bridge — on her own. In order to discover the bridge, the reader has to retrace her steps back into the text, moving against the flow of the words while wearing the electronic glasses in order to discover a new path that quite literally wasn’t there before.

In a sense, this is like turning back to an earlier chapter and finding that it reads differently than it did the first time, not just because it exists in a new context as a result of later chapters, or because something has changed within the reader herself, but because the words on the page have altered themselves for their own purposes. Books from Martin Amis’s Time’s Arrow, which narrates its story in reverse, to Choose Your Own Adventure novels have experimented with asking the reader to move through its pages in manners other than the conventional left-to-right, beginning-to-end—but by creating the ability for the text itself to respond to conditions created by the reader, the tools of digital games expand those possibilities dramatically. It’s as if the earlier chapters in a book developed new words and sentences and had to be revisited after a later chapter revealed some crucial piece of context.

This is like turning back to an earlier chapter and finding that the words on the page have altered themselves for their own purposes.

Participation is a powerful mechanic, and Device 6’s game nature makes the experience of exploration and revelation feel visceral in a way that merely reading about exploration struggles to match. In a book, the sentence “Anna put on the mask and discovered a bridge” can cause a feeling of triumph in the reader, but there’s something no less than magical in achieving it yourself.

Even as it makes use of game elements to go beyond the book experience, making it more immersive and reactive, Device 6 also illuminates fundamental aspects of the book that usually go unnoticed. One of the primary tasks of a video game is to create a space in which the player overcomes obstacles in order to reach some sort of a goal. Games may accomplish this through the creation of a two-dimensional map (think Pong, Pac-Man, or nearly any board game), or by repeating a series of pixels again and again with some minor variations, until it becomes a three-dimensional hallway. Device 6 uses text itself to create a space through which the reader passes, building upon but also replicating a set of tools that books tend to take for granted. Our use of these tools in a book — the syntax of motion across and between pages, in English left to right, top to bottom — is so ingrained as to frequently be invisible, but it’s there. Every book, every story, is a space through which we travel: one sound, one letter, one sentence at a time. Device 6 emphasizes and reconsiders this movement through text by making its words a map through which the reader is initially led, but which requires later that she retrace her steps back through the text into new, previously obscure corners.

Every book, every story, is a space through which we travel: one sound, one letter, one sentence at a time.

As in most media, there is a long tradition of books calling attention to their nature as media objects — Jonathan Safran Foer overlapping text in Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close until the page is nearly a solid mass of black ink; Bret Easton Ellis starting and ending The Rules of Attraction mid-sentence, itself an invocation of James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake; Cervantes making Don Quixote aware of the publication of his own adventures by the later chapters of his book. What is a bit more unusual is a book that dwells on the peculiar physical geography of textuality — think, say, of Gertrude Stein’s Patriarchal Poetry, in which Stein’s repetitions stretch the very possibility of visual tracking, forcing the reader to make physical contact — a finger, a pencil — to locate herself on the page. Only a handful of printed books do what Device 6 does: highlight, rather than obscuring, the way we move inside a text.

It is not accidental that we judge e-books for their success (or failure) in making the space and architecture of their text disappear into the act of reading. E-readers are praised when they make us forget that they are not books and criticized when they insist on presenting themselves as the objects that they are: blocks of text on a screen, navigated through gestures that never quite become unconscious. One of the essential tasks in literacy acquisition is the ability to move from decoding the building blocks of language — letters and words, syntax and grammar — to understanding the information and expression encoded within the language. Success is measured in part by internalizing the elements so thoroughly that they no longer require conscious effort. One level of proficiency is gained when the reader stops seeing letters and starts seeing words, another when the reader stops seeing words and starts seeing sentences, and so on.

Device 6, on the other hand, is able to point to the way books work by never quite seeking to become one. As a game that the player reads, Device 6 turns its text into a playful antagonist, and creates a set of rewards for the otherwise onerous demand that the reader continue to look at the text as an object in itself.