Lit Mags

The Danger of Calling Her “Baby”

Weike Wang recommends “It’s A Shame About Ray” by Lara Williams

AN INTRODUCTION BY WEIKE WANG

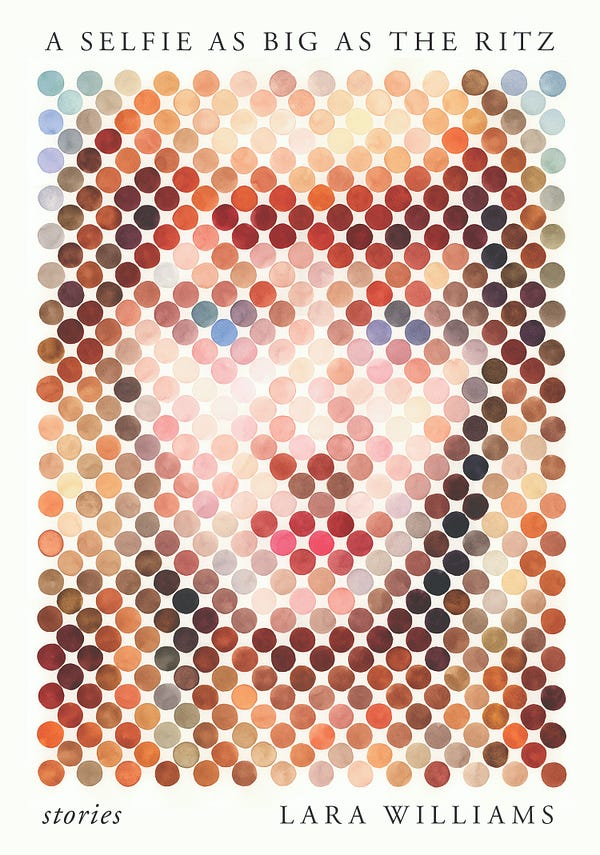

It was not that long ago that I started reading Lara Williams, but I am certain I will be reading her for years to come. Her slim yet powerful story collection A Selfie As Big As The Ritz arrived in my mailbox and I thought, let me just try one story. By chance — and would you believe it — that story was “It’s A Shame About Ray”. A week later, I finished the collection.

For me, a good story is provocative, not only in its set-up and narrative, but also in its sentences. One of Williams’ many talents is starting you at point A and effortlessly taking you to point B. An example, from the second paragraph of this fine story: “[the couple] always called each other baby, babe, babes; it was their thing, but now they had a living, breathing baby, there was a hesitation in it, something else that needed shifting.” Then the thread of babe, baby, babes moves through the story, growing stronger until it finally slips into place.

By this point, I have read “It’s A Shame About Ray” four times. The first two in one sitting — the story’s quiet but necessary ambiguity begs a second read — and the next two in the past month. When I push this book into the hands of my friends, this is the story I first recommend.

Williams is a smart and funny writer. She uses details that in the hands of another writer would lose their punch. When Ray goes to the supermarket for cooked chicken he is relieved because “there wasn’t nuance in cooked chicken. There weren’t gradations.” That Ray thinks so intently about rotisserie chicken endears him to me. A few lines later, Williams delivers her witticism. Ray realizes that he is “the man” sent out “to score meat.” Each time I get here, I smile.

Yet the larger issues at stake for Ray, the couple, the family, are familiar as they should be. How does one live with something in the past that continues to resurface? How does the mundane begin to take on a new meaning? As I believe human experiences tend towards the universal, I admire that at the core of each story, Williams sticks to the familiar. Her writing however, her style, her voice, are anything but.

Weike Wang

Author of Chemistry

The Danger of Calling Her “Baby”

Lara Williams

Share article

“It’s a Shame About Ray”

by Lara Williams

Ray had given up answering questions. There seemed to be, he thought, too many of them. Best to just go with the flow. Be that guy; some easy-going dude, in sunglasses and a papaya print shirt. That guy didn’t hit fifty, take up jogging and have an embolism. That guy didn’t split a dick trying to find decent asparagus, ambling around puzzled; all salt and pepper hair at the Sunday farmer’s market. That guy embraced his paunch, the inescapable inevitabilities of age, the unconquerable ravages of existence, replying “whatever you say, doc!” when asked by his GP if he’d considered cutting down on salt, then went straight out for burgers. That guy was alright. That guy was, as you might say, a cool guy.

“Hey, baby,” his wife called from the nursery. They’d always called each other baby, babe, babes; it was their thing, but now they had a living, breathing baby, there was a hesitation in it, something else that needed shifting. She was perched halfway up a ladder, holding the handle, her hair pulled into some vegetal tangle. What was she doing up there? — pawing at the ceiling like a mad thing, feet over the ground, like her body was some unbreakable, undamageable object. He imagined her falling, the slap of her skin and the crack of her bones, and felt jets of adrenaline surge to his heart, a geyser of dread; then recalled his persona, his cool guy schtick. “What do you think?” she asked, fixing some paper birds, some whimsical mobile, over the cot. He held his hands up — I surrender! — shrugging his shoulders, flexing his face. The rehearsed gestures of the recently laidback. She fussed with it some more. The nursery was half-done, in flux. Vinyl wall stickers, scattered stars and half-moons, on the right, on the left, Anita Ekberg, head thrown back, breasts thrust forward, rhapsodic, in the Trevi Fountain. Oh! — it had been quite the guest room.

It would take the weekend to finish the job, the transition near complete, the house almost fully baby-proof. “We’ll soon be set,” he’d said, regretting the phrase, which jarred, summoning images of insects set in amber, jelly tough as varnish. Whatever remained in the mold, doomed to stay there, forever.

He navigated the peripheries of the room, his feet pressing tenderly against the carpet. Since the baby’s arrival, the household had changed. Changed not in the plastic bottles that were everywhere. Changed not in the breast pump that lingered to the side of the bathroom sink like a perplexing adult aid. Changed not in the used nappy containing a single brown blob, which remained on the countertop for hours; the nappy’s frilled edges the split shells of a clam, the blob an offered pearl. No. The changes were more abstract, more semiotic. He increasingly found himself bumbling around in socks and soft clothes, feeling like some senile old fool, some forgetful old pop pops, a lost guest in his own home.

“Things,” his wife said, descending the ladder, with infomercial grace. “We need things.”

Things were her latest demand. An abstract bric-a-brac she willed at random. Like the space around them was significant. Like it needed filling. It was as if she had plopped this squirming animation onto the planet and couldn’t figure out why he too could not create something from nothing. Baby, we need things. Baby, we need stuff. Baby. Baby.

“You can get all this from the supermarket,” she said. “I’ll write you a list.”

She left the room, leaving him with the baby. He looked past him with blissful incomprehension. Babies, with their smug ignorance, their swaggering oblivion. How gladly and giddily they were bewildered. He was propped in the corner, moored to his mobile, with that glazed expression Ray had trained himself not to think too much about. A squidgy, unknowable tumor. A flesh thing. With shining white eyes, roly-poly wrists and the gurgling pomp with which he filled his nappy.

He started to whimper, a soft woolen whimper, as his wife called him from downstairs. Ray froze, unable to decide who to tend to first, mother or baby, apples or oranges. She returned upstairs handing him the list, picking up the baby, who immediately settled. Babies, Ray had concluded, were mostly stupid. But this they did understand. The implicit responsibility of their mothers for them.

Ray scanned the list. It seemed straightforward. “See you later, honey,” he whistled, leaving, and she kissed him on the rough shadow of his cheek. He was trying to introduce honey into their hypocoristic vernacular. Honey was neutral. Honey had no further implications beyond sweetness.

Ray recently found supermarkets stressful. He was used to stress. Of course, he was used to stress. But it was a different kind of stress at the supermarket. Different to the scattered flotsam of swaddling on their living room floor. Other to the lockstitch zigzag of the rush hour drive. The wolfish snapping of the customers, the hummed din of the registers, unique to the shop floor. Life, Ray had decided, was exchanging one type of chaos for another.

He paced the aisles looking at all the things. The crackling packeted things. The primary-colored cardboard things. So many things. All reaching out, wanting to be chosen. He felt like the world was perennially bulleting questions at him. At every turn there was another question; semi or skimmed, paper or plastic, cash or card; another question that needed an answer. Like the whole world was made up of two lost halves of a whole, searching for each other, eternally.

Beneath the requests for wood glue and mason nails, his wife had written “one cooked chicken,” he noticed, with some relief. There wasn’t nuance in cooked chicken. There weren’t gradations. You just picked the thing; you just picked the one thing. His wife had taken to eating chicken since the birth when she’d been practically vegetarian up until then. Ray assumed it was something primitive, something lunar he didn’t understand; to do with nesting and menstruation. He, the man, sent out to score meat.

He approached the rotisserie, the chickens circling in front of him, roasting to a red gold crisp. He stared at them, entranced; the methodic spin of the rods, the earthy odor, broken, when he noticed the butcher in the background, yanking apart the legs of a pink, plucked chicken, forcing his hand inside, pulling out the giblets. Ray felt suddenly sick. He squatted, with his hands placed over his knees, the world a swirling Lazy Susan, swaying in tandem around him. He tried to forget the scene, as he had tried to forget the scene it reminded him of; his wife lying supine, her legs pulled apart, the baby dragged out of her. How they had treated her like a thing, a meat thing, to be cut up and hollowed out. It had been an awful birth. A day he would forever remember as the worst of his life. He retrieved his phone from his pocket, prodding its glassy surface, dialing home, thinking if he could just hear his wife’s voice, if she could just give him some instructions, some direction, he’d be fine. “Baby?” she said, over the thin crackle of static, the shitty supermarket reception. He had the feeling of trying to suppress a cough, that convulsing heaving panic.

“Baby?”

On the way home Ray called in for a drink. It seemed like a cool guy move; a leisurely interval before they were set; elbows resting on the gravy polish of the pine bar, a single malt whiskey cooling with two cubes of ice.

He sipped his drink, feeling the heat settle in his stomach, wondering why all comforts were thermal. The muted television flickered foreign atrocities, genocides Ray no longer felt pathos for. It was like grieving the seasons, pining the moon; it was so far away, so abstract, it seemed senseless to engage. Even the television didn’t look like a real-life television, like a television within a television, a film within a film, a dream within a dream, the way a life could feel like a life within some other life, some scripted, unknowable life, some non-linear narrative. Well flip the script, buddy! Ray thought. Spoil the ballot! Throw your homework onto the fire! — as he knocked back the last of his drink and considered asking the guy next to him whether we all saw the same colors. He ordered another drink, turning over the cocktail menu, thinking next he’d have a piña colada, easy on the piña, with a side of shrimp and fries.

He rubbed his face. The suggestion of stubble. The threat of it. Resonating a satisfying scratch. Like the ice chiming against his glass, the clack of high heels on a hardwood floor. A bar sound. One of his favorite sounds. He wandered to the jukebox, put on some music; Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison, Pete Seeger. Some cool guys. Some guys who got it. He returned to his seat and wiggled his glass at the waiter, the way he’d seen in movies, gesturing for another, and then another; stamping his feet in time to the songs. Dance like nobody gives a crap. Drink like you don’t have a family to go home to. Love because what else is the point. By the time last orders arrived, he was a slop; as sloppy as an old sloppy joe, slopping everywhere, slopping his keys onto the carpet, slopping spittle from his jaw. What Ray learned about drunk driving that night is that no one intervenes, no one steps in; like wildlife documentarians, they let nature take its course. And when he came to, his head pressed against the steering wheel, a pool of blood in his lap, flashes of blue from the corner of his eye, he thought, sometimes all you can wish for in life is the physical manifestation of pain.

He woke up in a hospital bed, handcuffed to the rail. It seemed unnecessary. He really wasn’t going anywhere. He lifted up his free arm, bandaged, like lazy fancy dress. His hand had gone, removed; only a white stub remained. A giant q-tip. He told the nurse when he came to he didn’t care; and he still didn’t. What was a hand, anyway? Just another thing. Just another with or without. Everything was just a thing; there was no agency, no ability to affect change. It was the curse of the modern age, options; who needed options, when everything was essentially meaningless?

He thought of his wife during the birth. How he had watched her, her chest heaving up and down, like something equestrian, like something breathing because they meant it. Wondering how so much blood could come from one tiny human person. How he held the baby, but felt like he could be holding anything, any old thing, any old rock or piece of string.

He looked up; his wife hovered over him. It was the first time he had seen her since the accident.

“Baby?” she said. “Are you alright, baby?”

She seemed like she wasn’t really there; superimposed onto the scene, like the Cottingley fairies. She had this ghostly halo of gentleness about her; it was the thing he loved most, like she was from some other planet, lingering inter-dimensionally.

“Listen,” he replied. “Can you stop fucking calling me baby?”

He couldn’t bear to hear the word again.

He couldn’t bear to say the word again.

Mother or Baby, they had asked. A simple question requiring a simple answer. Choose your own adventure. Complete your character arc. They stood facing him, mint green and masked, eyebrows expressing emergency. Like bit parts waiting for their line, waiting for their SAG card. Mother or Baby. Mother or Baby. And he had said Baby. It was instinctive. He didn’t even recognize the voice that said it as his own. Decision made. He had let her go. Let her go like she was a thing. Bon voyage, sweetheart! See you on the other side.

Hospitals, he used to joke, were where you came when your body sprang a leak.

He’d registered some hurt, but it seemed insignificant, infinitesimal; a pinprick of pain among a swarming miasma of emotion.

One thing or the other; how could you choose between one thing or the other.

“Are you okay?” she repeated.

He looked past her, wanting to answer, wanting only to say the right thing.

He stared into the half-light beyond the hospital curtain, the corners gently heaving, in the clear corridor air. The lazily bleeping heart monitors, the silent hurry, the breathless calm, experienced as stop motion, snippets staggered, partially digested. His wife flickering in and out of focus. And a thought, somewhere, papered beneath the cracks, slippery and evasive and impossible to pin down; that everywhere, maybe, is exactly the same.