Craft

The Writing on the Wall: On the Convergence of Literature and Visual Art

On the best new writing blurring the line between art forms.

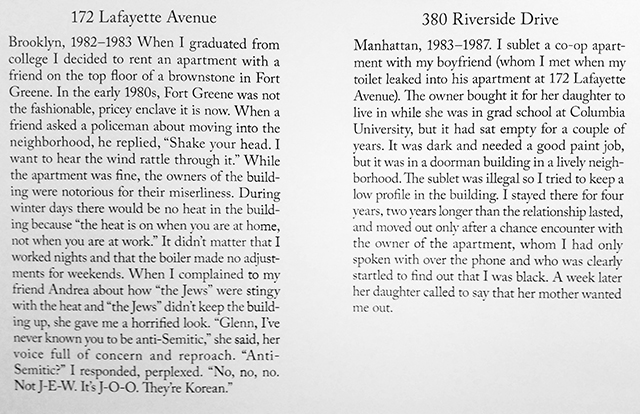

One of the most captivating works of nonfiction I encountered in recent years was not published in a journal or book. I read it while visiting MoMA PS1 to see their Greater New York exhibit. On one wall was Glenn Ligon’s “Housing in New York: A Brief History 1960–2007,” in which Ligon recounts his memories of the different places he has lived across the city.

In a review for Hyperallergic, Benjamin Sutton noted that the piece addressed themes of “gentrification, discrimination, and inequality”–the same concepts that have fueled many an impressive work of literature, especially recently. It’s a spot-on assessment: using a limited amount of space, Ligon is able to both evoke numerous spaces that he has called home, along with the complex dynamics at work in each.

This wasn’t the first moment of literary crossover for Ligon: Yale University Press released a collection of his writings, Yourself in the World: Selected Writings and Interviews, in 2011. In a piece for the Los Angeles Review of Books, Pete L’Official examined Ligon’s literary and artistic influences and the way that they converge in his work. Readers curious to read “Housing in New York: A Brief History” without traveling to a museum may be excited to learn that PS1 published a version of Ligon’s piece earlier this year.

It’s been a memorable time for works that exist in the overlap of fine art and literature.

It’s been a memorable time for works that exist in the overlap of fine art and literature. In the winter of 2015, I was taken aback after reading Caroline Bergvall’s Drift, a stunning book that juxtaposed meditations on traversing bodies of water with ecstatic explorations of language and haunting scenes of refugees seeking better lives via hazardous transportation over water. That same winter, I was stunned again after taking in Bergvall’s “Drift,” an installation at the gallery Callicoon Fine Arts which echoed many of the same themes as its literary counterpart but did so while engaged in a very different discipline.

Trying to pin Bergvall’s work into one category can be nearly impossible: Meddle English, her 2011 collection of “new and selected texts,” features one of the most fascinating collections of supplementary material I’ve encountered. Specifically, Bergvall’s accounts of the histories of the works collected in Meddle English often span continents and iterations, with certain works encompassing time spent in publications and in galleries. One can read Bergvall’s work on its own as literature, or as a counterpart to her work in galleries; one could also, presumably, focus entirely on Bergvall’s art and ignore her books completely. Any of these theoretical readers or viewers would walk away from the experience satisfied, with plenty on their mind.

Bergvall and Ligon are far from the only artists to be represented on both gallery walls and bookshelves. On a list of six recommended books that she assembled for The Week, the novelist Samantha Hunt included The Walk Book, a work by Janet Cardiff, perhaps best known for her large-scale audio installations. (Her 2001 The Forty Part Motet takes Thomas Tallis’s Spem in alium numquam habui and breaks it into its components; it’s both technically stunning and tremendously moving on a number of levels.) And Ben Eastham’s recent T Magazine profile of Heather Phillipson focused primarily on her work as an installation artist, but also noted the acclaim that she had received for her poetry: “Encouraged by her tutor, she applied for the prestigious Eric Gregory Award for poets under 30, and won; in 2009, she had her first collection published by Faber.” Eastham also pointed out that Phillipson has drawn inspiration from Frank O’Hara–who was himself a figure with a foot in the literary and fine art worlds, having spent time as a curator at the Museum of Modern Art.

The work of Sophie Calle, another artist whose work can be found in galleries and bookstores alike, has served as the inspiration for a chain of memorable literary works. The story behind Calle’s 1983 Address Book is the stuff of which great plots are made: Calle found a lost or abandoned address book, copied the contents, and reached out to the people listed in it, then documented her interactions with them. (Siglio Press published a version of it in 2012.)

A figure inspired by Calle shows up in Paul Auster’s 1992 novel Leviathan–specifically, an artist who selects people at random to follow, documenting those interactions. In turn, Calle went on to create a work inspired by Auster’s novel. Enrique Vila-Matas’s 2007 Because She Never Asked, newly translated into English, uses that as a starting point. Its plot follows a writer who is commissioned by Sophie Calle to write a scenario for her to perform.

Because She Never Asked rapidly increases the metafictional quotient. It alludes to Auster’s novel, for one thing, but also adds multiple layers of reality, including a character who serves as a doppelgänger of Calle. She isn’t the only example of this: the novel’s narrator also serves as a kind of surrogate or double for the author Vila-Matas, who has incorporated the art world into his fiction on multiple occasions: his 2014 novel The Illogic of Kassel follows the misadventures of a novelist who is asked to write in public as part of an artist’s installation. In this case, the book plays out like a comedy of manners set in the art world; Because She Never Asked reads more like a response to Calle’s work–a literary homage that features Vila-Matas working with some of Calle’s preferred themes and devices.

Enrique Vila-Matas is one of numerous artists and writers alluded to in Valeria Luiselli’s 2015 novel The Story of My Teeth. This novel can be read on its own, as a standalone work about a larger-than-life character who reinvents himself as an auctioneer and falls victim to a strange conspiracy.

But the novel’s origins can be found in the art world. Luiselli was commissioned to write a work of fiction as part of an art exhibition, The Hunter and the Factory, that was shown at Galería Jumex in 2013. In a 2014 interview with BOMB, she described the process.

I wrote it in installments for the workers in a factory. Originally it was a commission from the Jumex Foundation, an important contemporary art collection subsidized by the eponymous juice factory. Two curators, Magalí Arriola and Juan Gaitán, asked me to write fiction for an exhibition there, and I suggested the idea of writing a novel in installments for the factory workers. I wrote one installment a week, and each was distributed as a chapbook among them.

In her afterword, Luiselli writes about seeking to “link the two distant but neighboring worlds”–in other words, the factory and the cultural activities for which it provides support. It’s through her novel, which encompasses questions of class, geography, and perceptions of art, that she is able to do so. It also creates a number of lenses through which The Story of My Teeth can be read. Luiselli concludes the novel’s Afterword by noting its collaborative elements–from the installments in which it was written on through to the process of translating it for Anglophone readers. “[E]very new layer modifies the entire content completely,” she writes.

“Every new layer modifies the entire content completely.”

Luiselli’s novel, like Bergvall’s texts, exists in some middle space in which fine art and literature intersect. Other recent books have used devices and techniques generally associated with fine art towards narrative ends. Since 2015, the first three books in The Familiar, a projected 27-volume work by Mark Z. Danielewski, have been published. As readers of his earlier Only Revolutions or House of Leaves are aware, Danielewski is fond of textual experiments and incorporating manipulation of the book as an object into the act of reading it. In her review of the first volume for the Los Angeles Times, Lydia Millet observed that it was “performance art as well as book — a heterogeneous mosaic of content that can either, depending on your reading preferences, dazzle and intrigue or torment and repel.” That emphasis on structure also calls to mind Eli Horowitz’s recent novel The Pickle Index, which exists in three distinct editions: a set of two hardcovers, a trade paperback, and an app. When I interviewed Horowitz last year, he noted that the differences between the versions was significant. “It’s the same basic text,” he said, “but exploring how the form and the story shape each other.”

That interest in form and format marks one additional way in which the art world and the literary world, never that far apart, have begun to overlap. Perhaps this convergence is a subtle response to the addition of digital formats to the methods by which books can be read. This isn’t to say that this group of writers is repudiating digital publishing formats; instead, it’s one possible answer that can arise after asking questions of just what physicality means for a book. If that answer in turn spins off a host of hybrids and challenging works, so much the better for those who care about a host of artistic disciplines.