Books & Culture

There Will Be Tokens (But It’s Not That Kind of Arcade)

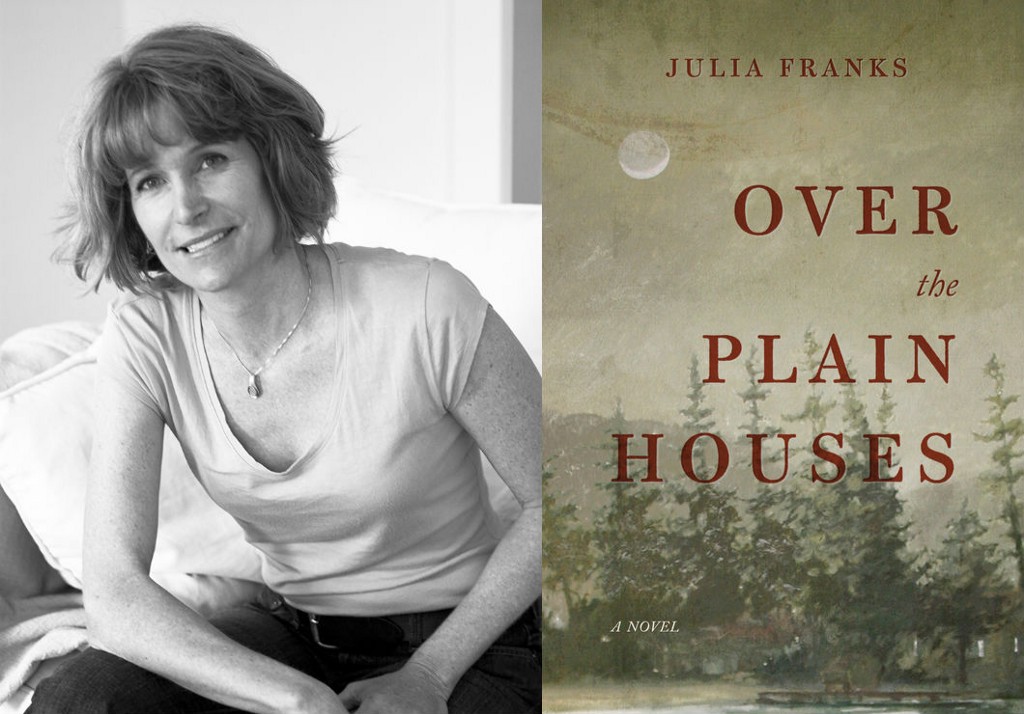

Drew Nellins Smith’s Arcade and its refusal to conform

There is a strange assertion going around the news dealing with the Orlando, Florida hate crime that took place at Pulse, a gay nightclub, in the early morning of June 12, during the club’s Latin night line. This assertion is repeated over and over again by various lawmakers and pundits, and paraphrased, it seems to be something like this: the victims weren’t just gay, they were Americans. A friend of mine wondered aloud on Facebook a few days ago how long it would be before us “gays,” meaning the LGBTQ community at large, would be demoted from the grand AMERICANS (which, by the way, not all of the victims were — there were several who were in the country illegally and the US oh-so-kindly agreed to give their families a whole week in our glorified country in order to attend to the wonderful task of funeral planning and body transporting) to being just “gays” again.

In that spirit, and directly after the massacre, I had the great pleasure of reading Arcade, by Drew Nellins Smith, a book that is both incredibly American and incredibly gay, and I’m pretty sure the latter trumps the former in this case when describing quality. It is also a book that very clearly sees and discusses the feeling of otherness that’s instilled in people questioning their sexuality and acting upon any deviant desires — that is, desires that aren’t het and cis.

Arcade, according to an interview with Smith in the LA Times, had some interest from one of the major publishers, but even after an editor told him to take out all the sex, the book still didn’t get out of the acquisitions process and was eventually turned down. When Olivia Smith — no relation to the author — editor at the excellent Unnamed Press, took on the book, her first editorial request was that the author put all the sex back in. And thank goodness, because without it, Arcade wouldn’t be what it is: a landscape of several months in which the importance of seemingly gratuitous sex scenes and the obsessions of a lovelorn man come together and are made equal, neither more important than the other.

[A] book that very clearly sees and discusses the feeling of otherness that’s instilled in people questioning their sexuality

The novel’s plot is not what the novel is really about, but in brief, it follows an unnamed narrator who occasionally goes by the false name Sam, as he very slowly overcomes an unhealthy obsession with “the cop” he was involved in (also never named) and the cop’s new boyfriend, “the kid,” who is 19, almost ten years younger than the narrator, and has replaced the narrator in the cop’s affections. It also follows the narrator’s discovery of a hookup spot whose front is an adult video store on the outskirts of the Texas town he lives in. And, finally, it follows his friendship with a gay man named Malcolm with whom he talks regularly and jerks off with.

The sex in the novel is nothing short of splendiferous — deserving of the word in that it is varied, fascinatingly intimate at times and completely detached at others, and unflinching to the point where some readers may be uncomfortable. Personally, I found it rather steamy. The arcade, which is really a series of booths in two corridors — one smoking and one non-smoking, very civilized — in which mostly men come together in various configurations and according to various codes is where the narrator spends much of the book. Though not meant as a manifesto by which to force readers to look at queer sex close up and accept it without flinching, it does have that unintentional side effect of presenting sex as both neurotic, which it is for many of us, and completely normal, as it is for many of the characters grazing at the narrator’s body and its outskirts (because the narrator doesn’t always participate directly but often watches from the corner).

There is something essentially satisfying about passages in books that present, intentionally or not, a metaphor for the novel as a whole. About halfway through Arcade there is one such:

One of the great gifts of the arcade was the way it put us all on the same level. Of course I could tell which men were rich or poor or middle class, but it didn’t matter out there. After the three dollar threshold, we were all the same. I went to the arcade when I was flush with cash, and at other times when I was so hard up for money I debated whether or not I could really drop a fiver on the venture. It didn’t change anything. It didn’t change my luck. It was the first and only level playing field I’d ever been on. I liked the idea that most of us never would have met or interacted if it hadn’t been for that place, divided as we were by our jobs and incomes.

This closes a chapter in which the narrator presents the arcade as incredibly different from his workplace (he’s a clerk at a motel, down on his luck after a career in real estate that ended with the crash of the housing market), and the next chapter begins with what struck me as a laughably apt continuation of this metaphor: “I drove to the cop’s house almost an hour away.” That is, chapters describing sex, chapters describing the narrator’s job, chapters describing his philosophy of the arcade, and chapters describing his outright obsession with his former lover — they are all presented as an equal playing field, none made more particularly important than others, even if we, as a society, would like to put some sort of claim on the importance of the narrator’s fascination with sex with other men, still a taboo subject in many parts of our society (and the novel is set, remember, in Texas, a red state with blue spots, but a red one nonetheless). The novel’s structure simply doesn’t allow that.

Another remarkable thing about Arcade is its refusal to be a coming-out novel. From its start, it’s clear that the narrator is interested in sex and romance with men, though at first he tries to explain to himself that it is just about the cop. He uses the philosophy of “I’m not into men, I’m into one man.” His actions belie this, of course, and he describes in passing how his coming out happened accidentally as he began to fall apart and cry obsessively about the cop whenever he was with friends or family. But that’s not what the novel is about; the narrator’s coming out is a byproduct of his personal realization that he’s gay, and even that isn’t what the novel is about. It almost doesn’t matter, except that it matters hugely because of the culture of the arcade (that of LGBTQ spaces historically occupied by gay men, spaces like bathhouses and other cruising spots) that the narrator becomes embroiled in and as obsessed with as he is with the cop.

Yet even so, it’s impossible to wrap the novel in any sort of simple “this is what it is about” narrative. As it’s a book in which both almost nothing and a great deal happens — both externally and internally for the narrator — it defies the notion of how we think of many novels. Still, there is a journey of sorts, and it is one that is worth following from its bitterly beautiful start to its bitterly wonderful end. The narrator’s frantic obsessiveness may be uncomfortable or overly familiar to readers depending on the state of each individual’s anxiety levels, but what is almost guaranteed is that the bafflement of the narrator’s actions, his difficulty in understanding himself even as he parses and analyzes every tiny thing he does, will be discomfiting because we’ve all been confused and lost and exactly where we’re supposed to be at one point or another.