Interviews

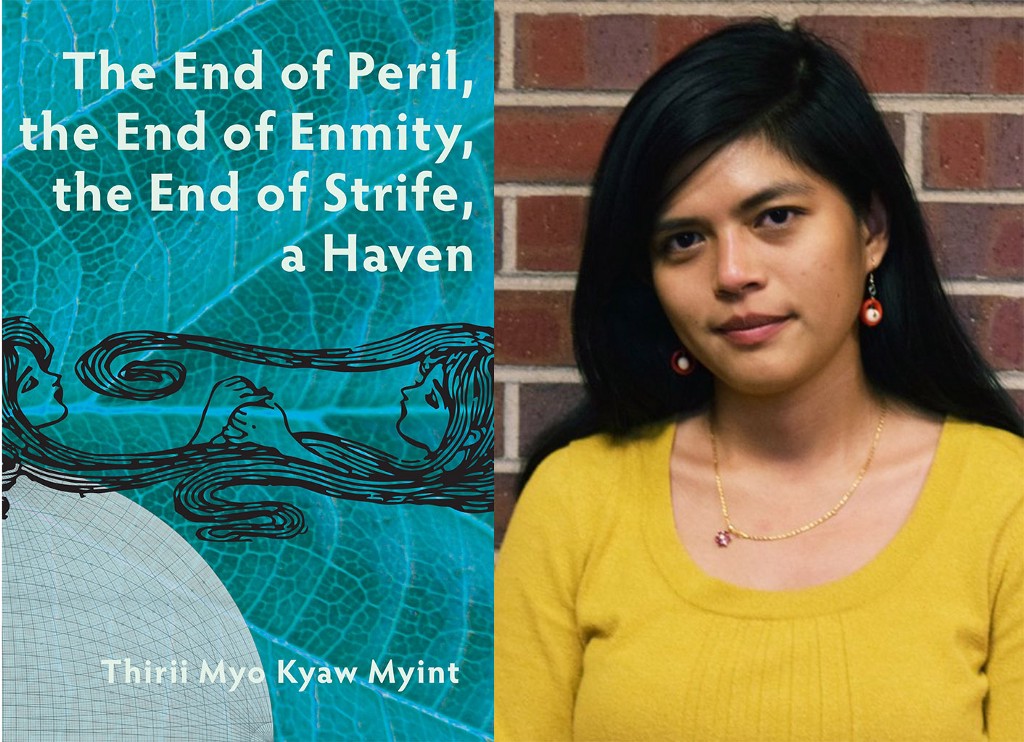

Thirii Myo Kyaw Myint’s Surreal, Haunting Post-Apocalypse

Thirii Myo Kyaw Myint‘s Surreal, Haunting Post-Apocalypse“The End of Peril” envisions an apocalyptic present both plausible and strange

Thirii Myo Kyaw Myint’s debut novel is a powerful work of art. Inspired by Myint’s exploration of embodying hybridity in America and Myanmar, The End of Peril, the End of Enmity, the End of Strife, a Haven tells the story of a young woman returning from emigration to confront “her inheritance of historical violence” while caring for her ailing baby. Through subtle and lyrical prose, the narrator attempts to understand her sense of belonging in a world that at first glance seems futuristic, but, in reality, is a world that devastatingly resembles our own. As the narrator discovers the nuances of her identity, the novel confronts a litany of contemporary themes, including suburbia, the legacy of colonialism, and having a gendered body. Luminous, fresh, and profoundly ambitious, The End of Peril establishes Myint as one of America’s most intriguing young writers.

From her springtime residency at the Millay Colony, Myint found time to generously reflect on her debut novel, the narrative possibilities of hyphenated writers, and how most of the world is living in a post-apocalyptic present.

Tillman Miller: The novel takes place in a post-apocalyptic future, however the details of the story feel fully-realized, lived through, and real. What inspired the story?

Thirii Myo Kyaw Myint: In my mind, The End of Peril takes place in a fictionalized, post-apocalyptic present, not a future. It is important for me to make this distinction because most of the world’s population (the “global south”) already live — presently — in the post-apocalypse. For a person like me, who was born in a postcolonial country, a so-called “developing” country, the apocalypse began centuries ago with European invasion and imperialism. That was the end of the world.

I began this novel because I wanted to write a post-apocalyptic narrative which acknowledged this reality. I wanted the apocalyptic event in my book to be directly linked to the apocalypse of colonialism. I wanted to show how those two events — the speculative apocalypse and the historical one — were actually one and the same, and taking place simultaneously in the present. In the Location of Culture, Homi Bhabha says the “post” in post-colonially doesn’t mean after but beyond. I wanted to show that this was also true of the “post” in post-apocalyptic. The world ended long ago, but it is still ending now.

TM: America is certainly one of the foremost purveyors of apocalypse. And yet, most Americans will justify purveying apocalypse because they believe America is an innocent savior with superior values. Have you found that unhyphenated American readers — when confronted with the fact that colonialism and imperialism have been apocalyptic to the “global south” — are unwilling to acknowledge this reality? Is that part of why you redirected your hope that the book would help break down stereotypes?

TMKM: When people find out that I was born in Burma/Myanmar, I find that they often want to talk to me about the military dictatorship, or the civil wars, or more recently, the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya — and always in a completely de-historicized, de-contextualized way. I am sure they are “just trying to connect,” but sometimes it almost makes me feel as if they are trying to remind me of how dysfunctional and oppressive “my” country (Myanmar) is, and how lucky I am to be in America. As an immigrant, I am often made to feel as if I should be grateful for having been “allowed” to “become” American. Only a few people have put it in so many words, but that is the general attitude I’ve encountered.

I redirected my hope for The End of Peril because I realized that it’s not my responsibility to change this attitude, so I shouldn’t make it my goal to do so. I admire and respect people who work to educate others, but I don’t want that to be my job. I just want to make art.

As an immigrant, I am often made to feel as if I should be grateful for having been “allowed” to “become” American.

TM: One of the beautiful elements of the book is the deft prose. It’s often haunting and ghostly, which echoes one of the pivotal ideas in the story, that people — mothers, in particular — are haunted by their family history and legacy. Can you talk about the importance of motherhood and familial legacy in the novel?

TMKM: As a child, I remember looking at my mother’s body and my father’s body and not believing that one day I would grow up to look like my mother. Even though I have a woman’s body now, whenever I see pregnant women, I still feel the same way I did as a child. I cannot believe that one day, I might look like them. Motherhood, for me, and for the narrator of The End of Peril, is the limit of the self, both physically and emotionally. It is the point when the self becomes the other, or becomes other to itself. Because the narrator is trying to understand her identity and where she belongs, the mother, becomes this fraught symbol she keeps butting up against. On the one hand, she is still trying to extract herself from her mother, to be separate from her mother, but on the other hand, she has already become a mother herself, already given birth to her own ghosts. She goes directly from being a child to being a mother, without the relief of being herself. Having a family, either in the past or future, I think, is the condition of always being only partially oneself.

TM: Do you consider The End of Peril to be speculative fiction, magical realism, or something else entirely?

TMKM: I think that markers of genre, like all other markers of belonging, are markers of difference, of deviation from a normative center. In the same way that “man” is unmarked and “woman” is marked, “fiction” is unmarked, while “speculative fiction” is marked, and “realism” is unmarked while “magical realism” is marked. I consider The End of Peril to be fiction and realism. It is my interpretation of reality. If the book is strange, it is because I am strange, the way every single person is strange. The “normative center” is, after all, a social-construct. I truly believe no one is normative, no novel is normative, and that reality is nothing like realism.

If the book is strange, it is because I am strange, the way every single person is strange.

TM: There’s a moment near the end of the book where, for the first time, the narrator appears to understand her identity and her desires. The narrator expresses love for another girl and it seems possible that the world can finally accommodate this desire. Does this moment offer the narrator access to something that she’s been denied her whole life — access to hope and freedom?

TMKM: I love your interpretation of the relationship between the narrator and the girl. I think at the end of the book, the narrator does come to realize that she wants to be with the girl — not with her mother and father, nor with the baby — and this realization is empowering and freeing for her. I don’t think, however, that the narrator understands her desire as an identity. I don’t think the love between the narrator and the girl can be labeled as romantic or sexual or platonic. It is simply love — intense, pure, and complicated.

TM: When the narrator says, “My mother does not let me forget I am descended also from the enemy. The raiders from the north who drove the king’s men to the end of peril,” what is that a reference to?

TMKM: In the novel, the narrator is descended from two ancient/mythological peoples, “the king’s people” who are native to the harbor city, which they named the end of peril, and the enemy who are invaders from the north. The two groups are fictional and function as almost mythological tropes: the agrarian civilization, and the nomadic raiders. There are stories of conflict between such groups in many cultures. In the narrative present, the people who live in the end of peril are descended from both of these groups which are “one people now.” The narrator’s mother, however, holds onto the mythology, and reminds the narrator that “[she] is descended also from the enemy,” that some of her ancestors were invaders. It is important to me that the narrator’s understanding of her identity is complicated in this way because I did not want her to be able to view her return to the harbor city as a true homecoming. I wanted her to be wary of the idea of a pure ethnic group, or a pure homeland.

Finding Black Boy Joy In A World That Doesn’t Want You To

TM: There are elements of feminist dystopia in the book. Women are blamed for the sky flying away and the narrator considers disguising herself as a man to defend her country and become a hero. As a result, it seems as though parts of The End of Peril can be read as a condemnation of misogyny and the chauvinistic power structures that currently exist in Burmese society. Was that deliberate? Were you intending to look at the experience of Burmese women and examine a cultural source of oppression?

TMKM: The story about women being blamed for the sky flying away was something I read while taking a standardized test on reading comprehension. I don’t even remember what culture the story originated from. In a way, it doesn’t matter, because the story is universal: women are universally blamed. As a Burmese-American woman, I was well aware that the feminism in The End of Peril might be read by un-hyphenated American readers as a condemnation of Burmese society in particular, but in fact, I meant it to be a condemnation of all misogynistic societies in general. The last thing I wanted to do in this book was try to represent or speak on behalf of anyone, especially people I had little interaction with and knowledge of, such as “Burmese women” (an unwieldy category even for a dedicated expert since the country is so incredibly diverse). I cannot speak about or for Burmese society or Burmese women because I did not conduct any research on those topics for this book. I have however, lived in America since I was seven, and have been a woman since I was eighteen, so I did deliberately try to condemn “misogyny and chauvinistic power structures” that I observed and/or experienced in current American society. The “domed city,” in my mind, is an American city, and it is where the narrator grows up, and comes to understand what it means to be a woman. The main “cultural source of oppression” that I examined in the novel, then, is actually American culture.

The feminism in “The End of Peril” might be read by un-hyphenated American readers as a condemnation of Burmese society in particular, but in fact, I meant it to be a condemnation of all misogynistic societies in general.

TM: There’s no denying that scores of American readers need to broaden their canon. Can you share what books have opened up narrative possibilities for you in the way that you hope The End of Peril will open up narrative possibilities for readers? And who are the young writers you’re most excited about?

TMKM: The books that influenced The End of Peril the most were Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North (translated by Denys Johnson-Davies), Ama Ata Aidoo’s Our Sister Killjoy, Marguerite Duras’ The Lover (translated by Barbara Bray) and Fleur Jaeggy’s Sweet Days of Discipline (translated by Tim Parks). Even though I am a native English speaker who writes in English, being raised bilingual estranged me to English from the beginning, and I have always been drawn to literature in translation and works by multilingual writers in which I am able to (re)encounter that feeling of estrangement — that feeling that there is a distance or dissonance between language and experience, a gap. I like books that peer into that gap, instead of pretending that it isn’t there. Writers who are gap-seekers, who I am excited to read and follow are Valeria Luiselli, May-Lan Tan, and Sara Veghlan, whose novel The Ladies won the Noemi Press Book Award for Fiction.