Lit Mags

This Door You Might Not Open

by Susan Scarf Merrell, recommended by Fifth Wednesday Journal

AN INTRODUCTION BY RACHEL PASTAN

We all have stories that refuse to let us go. We read them, they wrap their tentacles around us, then we carry them trailing behind us for years. Possibly this happens to writers more often than to other people, or maybe it’s just that, when it does happen to them, writers are more likely to let us know. Sometimes, after years entwined in a story, something magical happens — some mysterious alchemical exchange. Then, bit by bit, the story wriggles free from our hold, just as powerful but transformed.

For Susan Scarf Merrell, that haunting and haunted story is “Bluebeard.” If you don’t remember, “Bluebeard” is a nightmare commentary on power roles in marriage in which the price of wifely disobedience is death. In Merrell’s brilliantly original evocation, “This Door You Might Not Open,” something crucial has changed: the wife, through casual inattention, has broken the spell, and now it is the husband who obeys her, bringing her a hairbrush, engaging Ina Garten to cook dinner, even shaving his trademark beard. (“I do not like a beard,” the narrator, Alice, tells us.) All this he finds time for amid the tasks of daily magic that his job requires he perform: from making rain for the crops out of brown clay shaped into baby’s tears, to opening the new Wegmans supermarket. These two modes — magical and mundane — coexist in compelling tension here, as in much of Merrell’s fiction.

Exploring how the world is changing is central to Merrell’s motive, but what I love most about this story is how it sets modern questions in a world that still feels enchanted, crepuscular, alive with the unbounded possible. Partly she does this through the way she uses language. Her prose is both clean and incantatory, and she knows when to explain and when to leave a mystery. In a kind of prismatic sorcery, we see the old “Bluebeard” story in a new way, yet at the same time we feel the hundred tenacious threads that connect our new world with the old one. In both, Merrell suggests, marriage can be perilous territory. A locked, bloody room inside which anything can happen.

Rachel Pastan

Editor Fifth Wednesday Journal

This Door You Might Not Open

Susan Merrell

Share article

Recommended by Fifth Wednesday Journal

My mother wishes most of all for a home that cleans itself. As far back as I can remember she has talked about this. She is turning fifty, ancient for women in my family, and I would like to honor her. Carl says it would be easy to do. A minor spell.

When can we give her the magic, I ask?

But he demurs. Dirt is what makes clean beautiful, he tells me. Certain dreams are better unfulfilled.

Carl, entering through the kitchen door on the afternoon of his first day back at work, is in a good mood. He stopped for beet greens and a fresh-killed chicken from the outdoor market. He was treated royally at the poultry farmer’s stall. He did not have to wait in line; his proffered twenty was rejected. Carl puts the chicken on the counter and watches my face until I remember to give him an approving smile.

We have been pretending all is as it used to be. My family’s curse is broken. His has begun. Why rub it in? I hope to be a kinder tyrant.

In the evenings, lately, Carl and I watch cooking shows on television. He finds knife work infinitely fascinating. I like the way the chefs imagine combinations I would never consider: saffron and chocolate, Aleppo pepper and rose petal, palm sugar with lavender and thyme. Some of the best combinations may not yet have been considered, as Carl pointed out soon after the change between us happened. The obligations of his clan had come to wear on him. He says he is relieved. “The infinite is real, Alice,” he tells me. I snuggle closer on the couch and kiss his neck.

He now shaves twice a day. Rough beard; I swear I can see it growing. He used to wear it long, so that his wife at the time could comb it out at bedtime. I do not like a beard.

“Love is not love which alters when it alteration finds,” I tell him. I want to say something original, but everything — between us and about us — has already been said.

“You are a verse,” I tell him.

The villagers have asked for rain, and tonight he takes an hour to shape brown clay into baby’s tears. The table is littered with the impossibly tiny drops; the dirt under his fingernails would make another dozen. “I am the chorus,” I remind him. It used to be the other way, you see.

I don’t expect an answer. The new ways we are creating leave room for silence. Building bridge struts from folded origami birds that flutter into place, clearing fields with a flung glove: still his purview. Shall we let the villagers know that they are safe? He will not kill again, except on their behalf. He has promised me. He has promised me.

The villagers dressed me in black for our wedding. My mother hugged me tightly, believing we would never meet again. I was the last daughter in my father’s bloodline, and she had no one left to give. Did I know my fate? I’m not entirely certain. I was like the rest of my sisters, my aunts, my cousins — I did my job. I did not think about what was to come.

When I appear with him at town council meetings — he no longer attends without my support under at least one elbow — they study me. I measure admiration and fear; neither is the winner. But I am. I am the chorus that returns.

My mother telephones. “What happened? No one has ever — how did you survive?” She is relieved; I think I hear this in her voice. Also curious. There are details none of us have ever been alive to share. And also, there is this: now she will have to get to know me; I am no longer a sacrificial lamb.

I tell her I left the egg outside the room, the one he told me I was to carry always. “Death comes to anyone who drops the egg,” he said before he left on that first journey, a few months into our marriage. In his voice, I heard regret — eons of it. Not simply his own, but that of his brothers, his father, his uncles. (No one lives forever, not even Bluebeard.) His family has always preferred mine.

And me? The fact is, I forgot his orders. Or so I tell myself. Some weeks after his departure, I placed the egg on the table in the hall, watched it wobble for a moment, and went inside the room.

What I saw there I do not share with my mother. I do not share with anyone. The plump mouse that gnawed at Isobel’s toe, that’s what I remember, and how its eyes assessed me expectantly, how it did not bother to be frightened of an intruder. It merely wondered how I would taste. Dried blood crusted the tatters of her jeans and what was left of her brilliant brown hair−strands dotting the bones of her skull. After death had been no kinder to her than life, and she my favorite, my dearest, the sister closest to me in age. The freshest corpse. I saw others, my sisters and my aunts, I saw them all, but Isobel is all I can remember. I squeeze my eyes closed, picture the man my husband has become, the way he holds me on the sofa, how he says he loves me more because I broke the rules. Because the egg stayed outside, he does not have to kill me. He didn’t want to kill any of them.

The curse is broken, I tell her.

“I didn’t know it was possible,” she says. She believes in Bluebeard, what he provides for our village. She married my father knowing any daughter she produced would have to die. I have always found her cold, but I begin to understand her.

I say, “Why didn’t you tell me what he is?” It was not fair.

She says, “Nothing is fair.”

She says, “There was no point.”

She says, “I wanted you to be happy for as long as possible.”

I am happy now.

He shakes his head no when I ask him to do the dishes, but then he does them. He does anything I want. “Bring me my hairbrush,” I command, and because he cannot help himself, he pushes aside the pile of bedclothes, clambers down from our high bed. If I have left the brush in my bathroom, he raises the lights so he can find it. When the moon is full, I hear him tossing and turning like a woman whose reds are controlled by ebb and flow. He has become like the sea, all strength and no purpose. I do not fear him.

“Sing me a song,” I command, and when his voice cracks into tenor, I close my eyes and pretend I am not listening. My head aches with the effort it takes to make no effort. He braids my hair; I tell him not to pull the strands so tightly, and he murmurs that he is sorry. He does not miss the man he was.

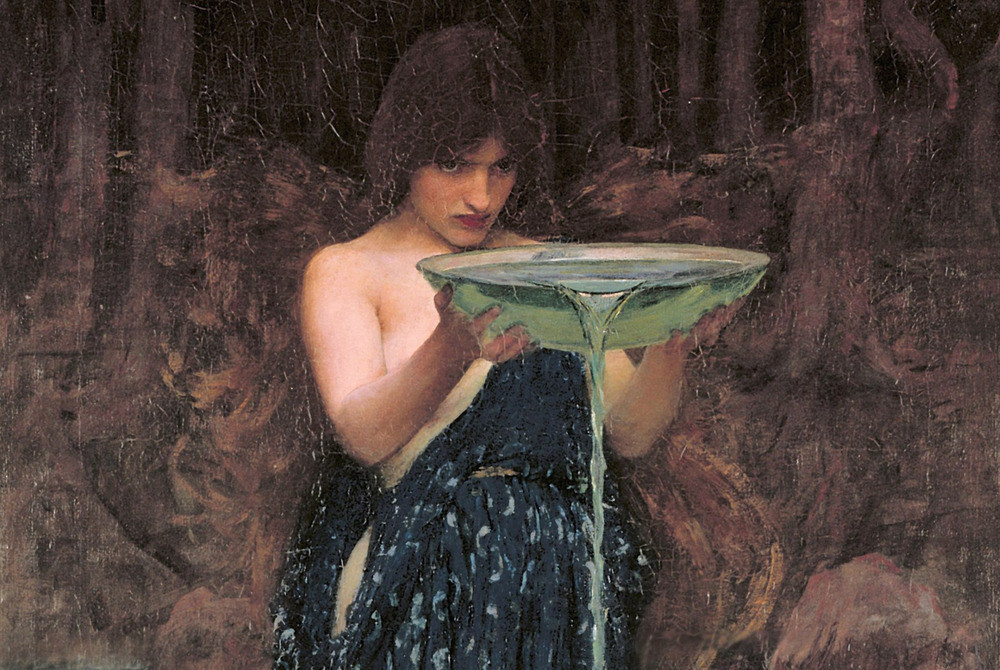

I was provided to him under village statutes. He required a new wife. My family has been fodder for his as far back as anyone remembers. In the uncles’ chamber in my parents’ house are files full of contracts, the correspondence ritualistically identical for each new bride. The walls in that room and in the formal parlors are lined with paintings and (for recent generations) photographs: we have always been well honored. Look at the formal perspective of that Renaissance master, the subtle tones of Wyeth’s brushstrokes! See how our hands are never clutched in fear, or splayed in longing. We are proud, all of the Mansfields are proud! I asked for oils, though my sisters were photographed, Mara by Richard Avedon, Isobel by Annie Leibovitz. Look at our portraits! Museums would salivate to own these beauties. No expense was ever spared to memorialize our sacrifice. Loved? Perhaps. Doomed, yes, yet ours has been a noble profession.

Why does this surprise you? We inherit beliefs, along with eye color and a position with regard to cilantro.

“Did you want to kill me?” I ask again because I want to be sure. “You expected that you would.”

It is afternoon, the sun is high and hot, and we are in our bed letting the dull wind drift over our bodies. He says, so quickly I like him for it, “This is the job my family does. It has duties. I never allowed myself to want.” I put my hand on his thigh. I say, “You like this now.” He nods. He says, “I wonder what comes after us?” We are silent. Neither of us has the answer.

I gather eggs for breakfast. This is the job I chose to keep for myself alone, a private joke. So private I am the only one amused. For breakfast, he makes omelets. I like to see him crack the eggs; his mouth tightens as if each tap on the counter is a knife dissecting wrist from hand. I do not pity him.

“We are going to have a child,” I say one morning. He drops a plate into the sink, but it does not break. Under the faucet stream, it seems as if his hands are shaking. “I’m so happy,” he says finally. I think perhaps he is.

He has always had this house, with its long crenellated roof, and its many rooms, and the grassy slope that smooths down to the county road like caramel. When I was a little girl, my older sisters and I would sit on the high stone pillars and throw horse chestnuts onto his land. He was my sister Mara’s age, and he loved her first. Then Cynthia. Isobel was next. I do not forget this. The house belonged to his great-grandparents, and their parents before them. There has never been a time when our village existed and this house did not. When I moved into it, he mentioned difficulties. What happened to my sisters had been unfortunate. “I am aware,” I told him staunchly, pretending I had all the facts. I had none of them.

For one thing, I had imagined I would find Isobel. That she was hiding here, waiting for me. I knew about sex, about getting stains out of laundry, about thank-you notes. I am not a creative woman, I suppose. In any case, I had not understood.

The baby is a girl. She has a fragile, pale exterior, as if any jolt might harm her, and I fear for her, but do not let her father know. Nonetheless, he shares my worries; he does not like to let her from his arms. He wishes to take her with him when he goes to work, but I do not allow this. I tell him no, leave her at home. Obedience is required, and yet he does not leave her. He will not leave her. Difficult to move rainclouds from one pasture to another when only one arm is free; he did not tell me, but one of our neighbors confided that he set fire to a small section of the Hudson River two weeks ago. If Miriam Dougherty feels free to tell me this, I am certain that others are gossiping behind our backs. That can’t be good.

And now my mother has emailed to tell me she intends to visit. This has never happened, not with me, not with Mara, not with Cynthia, not with Isobel. It has never happened. Carl does not look as tall to me; his shoulders curve from his neck as if his back might begin to hunch under the baby’s weight. I want her to walk, I tell him. My voice is firm. “Listen to me,” I say, “She has to grow up, no matter what happens. We have to teach her, we have to make her ready. That’s what life is.” He puts our dinner on its plates. He has made lamb stew, with spinach and sweet potatoes. Tendrils of steam rise as if from his hands as he places my meal before me; my stomach muscles soften in anticipation; I smooth the skin of my fork.

And this is what he says, as if I don’t already know: “Everyone answers to someone, Alice, even me.”

You answer to me, is what I want to say.

Carl is asked to preside over the opening of the new Wegrnans supermarket. The stores are large and modern and clean, the prices are good, and they have a huge organic section. Nonetheless, we are both taken aback by the request. We do not talk about it. My mother arrives just in time for the opening; she is very excited to hear we are getting a Wegrnans and says she will visit frequently because of it. She has six insulated grocery bags in her car.

“The world is changing,” Carl says, as if I am too inexperienced to notice.

“What will you do for them? Freeze the ice cream?”

He is putting various supplies into an insulated bag just like the ones my mother brought. They have not yet said hello to one another; it is as if my mother cannot see him, as if he is only real to me. Post-it notes in various colors, a plastic container of toy soldiers, some cotton balls and silver glitter. Baking soda. A length of gray thread.

My mother wants to go ahead before us to make sure she gets a place. She offers to take the baby, and for the first time Carl looks at her directly. “No,” he tells her. “That’s my job.” Then he asks for a trowel, some chicken dung, and a box of matches.

My mother says she is not frightened of him, not any more. That no one is.

“Shh,” I tell her. Why is everyone so nasty? He did not want to do the things he did. It is the way everyone blames the woman who has an affair with a married man. My family is also to blame. My mother is obediently silent. Either she is a good guest, or she has figured out the same thing Carl has.

I am the chorus, I think to myself defiantly. I am the chorus that reappears. There has never been another woman like me. I tell her to get in the car; I will drive us there. Carl sits in the back, his hand on the baby’s car seat. I watch them in the rearview mirror. “You look handsome,” I tell him. When we arrive at the grocery store parking lot, my mother takes out a tube of coral lip stick, but there are so many people watching, waiting to greet us, that she doesn’t get a chance to put it on. The clerk who helps me from the car compliments my outfit. I smile at Carl. We picked my jacket out together.

Then I say, “My mother will take the baby. That way, you have both hands free.”

When I place her in my mother’s arms, Carl shudders. The baby’s skin glows against the pink of her lips. Her eyes are marine blue and always watching. She is not afraid.

At first, Carl has trouble with the spells, but eventually he settles in. The crowd likes it when he sends the boxes of breakfast cereal floating high above and has them waft slowly down, a gift from the store. Later, in the car, I mention that the first flourishes were not up to par. “A little embarrassing. You can do better.”

He has the baby on his lap. He shakes his head absently, busy fitting her into the car seat. My mother wipes some spit-up off her shoulder with a wet nap.

Carl was ill for nearly two months after I went into the forbidden room. I was not ill; I was — something. Angry? Confused? I don’t know the word. If no one has ever survived but me, what does that say about my family? Generation after generation, century after century, and I am the first woman lazy enough to place the egg on a table before stepping over that threshold? He had told me the egg was my responsibility, that I must hold it in my hand or keep it in my pocket no matter where I went or what I did. He told me it was tradition. It was my job. I think of Mara and Cynthia and Isobel and all the aunts that came before me. We are responsible women, we fulfill the requirements of our clan. For all I knew, the egg was what kept my family alive. And when I placed it on the table outside the forbidden room, I wasn’t thinking about them at all. I wasn’t thinking. I just put it down, the way I might do to brush my teeth. A moment here or there, and all the world is changed.

I shrink from the knowledge that I was as close to death as anyone else. To change history I would wish to have been purposeful and wise. But what is true is often not pretty.

His strength returned slowly, as did the color in his cheeks and the shine to his hair. One morning, he said that he was ready to dress, to come downstairs. I told him I would help to shave his beard. Comb it, he said stupidly. No, I told him, we are cutting it off. I do not like it, I explained.

The baby and Carl and I rent a house in the Hamptons for August. I trust he will be able to speed us through the traffic jams on Route 27 and get us into all the best parties. I have a hankering to meet Ina Garten and discuss cooking with her, and Carl assures me this will be easy to manage. Our house is a modern home, on the ocean, and I like the way we are visible to the vast blue-gray expanse and the horizon while protected on the dusty dirt road side. The babysitter we hire is short and plump, and has a funny name — I think it is Amina, but never feel it is the correct moment to ask again — and she recommends a cook and housekeeper. I tell Carl I would like to hire Ina. He studies the outsize black and white photos of English castles our landlord has placed ironically over the fireplace and says nothing.

In the evening, however, Ina is there, cheerfully describing the rib-eye steaks and duchess potatoes she is making for our dinner, her interactions with the camera crew and support personnel so practiced and off-hand that I almost imagine she is there only for us. The meal is delicious. I ask her for her shortcake recipe and she says she uses cornmeal. I ask her to return and cook for us again, and she murmurs something noncommittal. I tell her I would like to meet some of her friends. “Yes,” she says, but her tone is neutral, and then the two young women who have loaded up all her equipment in large brown tote bags usher her from the house. When she is gone, the silence is deafening. Even the baby’s cries are not as loud as the swirling confidence of fame.

“I want to tell people about you,” I say to Carl. “About us.”

Carl arranges for me to be interviewed by Jane Pauley, who has been given an hour-long slot on network television in the late afternoon. This is a new opportunity for her, and it seems fair that she be allowed it, given all she has done for the medium. I like her. She has a soft and friendly energy. Jane and I do several long shots of us walking along the beach in front of the rental home. Although I am far taller than she, it feels as if we are the same height. The white caps on the waves have a certain ominous gray soapiness. And then we sit in the living room, where the camera crew and Jane’s staff hover officiously, and she asks me to describe what I saw inside the forbidden room. No set-up, no polite dithering, just the question. I should have been prepared. For a moment, I think I will faint, the entire room goes fuzzy like an Impressionist painting, and her face shimmers. “Jane,” I say, buying time, “I’m not sure you want to know.”

“That’s why we’re here,” she answers, shifting her trousered legs so that the toe of one pointy pump is slightly lifted, perhaps a better angle for the cameras. The surface of my eyes feels taut, as if I will cry. I can see Carl holding the baby; they are out on the deck, and the sun glitters in his hair, and I am a little frightened at what I have done, what he has let me do. And then the words rise like fuel or blood, and I am ready to tell. My sister Isobel was the one I saw, and I describe the way I found her. Blood in dry pools, her jeans stiffened with it, the way her neck lolled and the sparse remnants of her hair trailed. He had left her hooked to the gray wall. Jane is aghast, as if this is not the story she expected me to tell, when it is of course precisely what I had described for the cheery pre-interviewer hours earlier. Why was that so much easier? Cameras, I suppose. They make you believe your words are permanent as death.

I do not tell her about the mouse.

“How can you stay with such a man, such a brutal man? He should be imprisoned,” she says. Carl sits down with the baby, on the sofa near us, and he dandles her lovingly. Bouncy, bouncy, she has taken to standing on his thighs and bending her knees. She wants to walk. In the long silence, the ocean begins to make itself heard. I can feel my body pulsing to align itself, to find the languor in the crash and drag of the surf along the sand. Jane clears her throat, glances meaningfully at her producer. The silence throbs. Sunlight flickers across the photos above the fireplace, along the crease of Jane’s white slacks. The baby emits a sound; it is not glee or sadness, simply a coo, a statement of being alive.

The producer opens her mouth, about to prod us into further revelation, and Carl lifts one hand. Violets spray from the producer’s mouth, a firework of florals. Jane bursts into astonished laughter, and then the crew does, and then the producer says, “Can you do that again? For the cameras?”

Carl nods. Of course he can. Take after take until the camera crew is satisfied. I notice that Jane does not repeat her question. He has stolen my interview, but I try not to mind.

That night, before he puts the baby to bed, I mention to Carl that Jane has raised an important question. He has brought our girl to me in bed, so I can kiss her. He pets my shoulder with his broad, hairy fingers, and I latch onto them before I turn away, drawing his hand with me. It is dark enough for sleep in our beachfront bedroom, but the light the moon makes on the waves dances along the ceiling like so many shooting stars.

“I’ll take her now,” Carl whispers. “So you can sleep.”

I had been pretending I had already drifted off but now I change my mind and turn back toward him. “If she breaks, will you fix her?”

“The baby?”

“Nobody did that for me,” I say. Lucky girl. I am thinking that my mother raised me for death and principle. For ritual. To be broken was the reason I was born.

He strokes my back. “I would fix her,” he says.

I sit up against the pillows, take her in my arms. She is a fragile little thing. I meet his eyes directly as I hug our baby’s precious body.

His breathing goes faster. “Not so tight,” he says.

He is scared, isn’t he? And that is why I love him.