interviews

This Is a Landscape of Ghosts

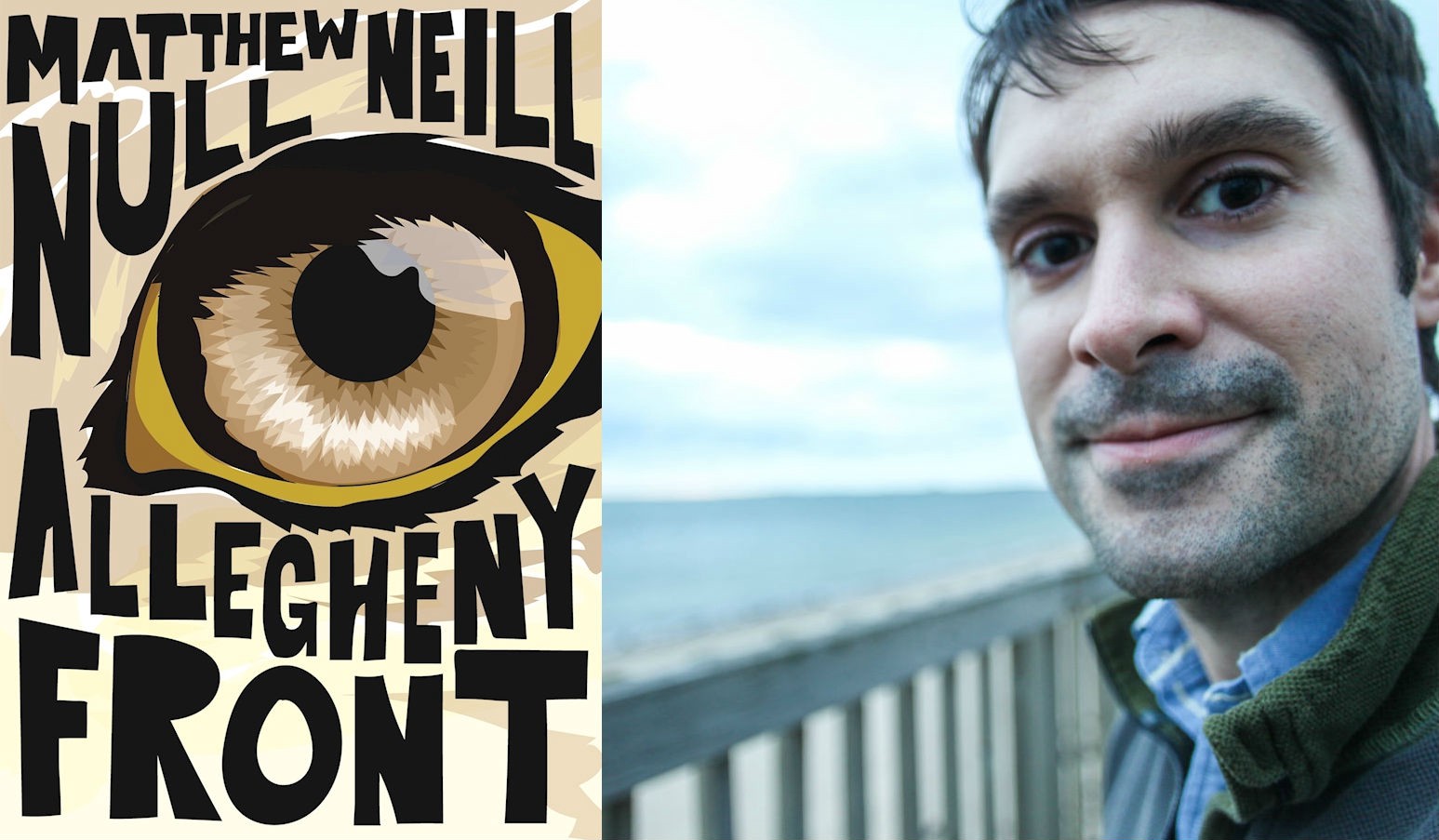

An Interview with Allegheny Front Author Matthew Neill Null

Matthew Neill Null’s collection Allegheny Front is as notable for the strength of its prose as it is for the ways in which it eludes expectations. One story focuses entirely on the shifting relationship between a group of bears and the humans living nearby; another story leaps ahead several decades at its conclusion to show how the aftereffects of its violent resolution are perceived in the decades to come by people with no knowledge of the events described. It’s a way of finding compelling drama in the spaces normally left blank in histories and stories, and it’s to Null’s credit that these stories never feel academic or dry. Instead, they’re as visceral and tense and the landscapes and relationships that they describe. I talked with Null via email about the roots of this collection, the influence of Henry Green and Shirley Hazzard, and how he found the ideal juxtaposition of humanity and the natural world.

— Tobias Carroll

[Read Matthew Neill Null’s story, “Gauley Season,” on Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading.]

Tobias Carroll: Landscapes, nature, and history all play a major part in the stories contained in Allegheny Front. Did you have an overarching theme in place from the beginning as you put the collection together, or did it become more apparent as you reviewed the stories?

Matthew Neill Null: Those are my concerns as a person from West Virginia, and predated my becoming a writer, so the theme cohered without my trying for it. My novel Honey from the Lion was dedicated For the land and the people. Allegheny Front is dedicated For the animals. Many of the stories pivot on fraught interactions between humans and animals. Too often the land is used merely as a stage, animals as props. For me there is a triangular relationship between humans, the land, and other forms of life. Without those three legs, the world tips over.

This is a landscape of ghosts more than one of the living…

This is a landscape of ghosts more than one of the living, as the population has cratered and the houses have gone to ruin. One’s gaze is forced backwards. My family has lived in West Virginia (and western Pennsylvania) for generations, from the colonial period on, so our history is imprinted on that land and vice versa, a legacy of settlement and decay. I could show you the creek-bed where my great-grandmother’s great-grandmother, a Huguenot woman, was scalped and killed. I helped a friend build a cabin there. We set up a portable sawmill and skidded pines off the flat. In order to pay off his mortgage, he had grand plans to sell it to a well-heeled person from D.C. along with some acreage, to someone hunting a rural escape hatch after 9/11, but ultimately it was too isolated to make good real estate. So he lives there now and takes his coffee where her body was found in 1786.

Those who live there experience the same struggle they had one hundred and fifty years ago: they love the land, yet are forced to destroy it in piecemeal fashion simply to get the money necessary to remain living there. Timber. Oil. Coal. Natural gas. It’s ghastly, but I don’t see any other way it could have happened. I’ve noticed that most people who criticize extractive industry live comfortable lives in suburban/urban contexts that are impossible without cheap sources of fuel. My family has taken part in all of it. If you live there, even if you aren’t directly taking part in extraction, you are providing services for the workers who do. Which has saved us from the sin of sanctimony.

TC: Over how long of a period of time were these stories written? Did you find that you had to be near the landscapes described in the stories in order to more accurately depict them?

MNN: Between 2008 and 2013. During the same period, I wrote my novel, Honey from the Lion, which was set in a very specific place and time (the high timber-camps circa 1904), so the stories served as a counterpoint as well as a rest. Now and again I craved to write about a time when people could use cellphones. Range around, you know? Also, the lumber camps were by definition a male world, so stories like “Telemetry” and “Mates” allowed me to explore female characters in a fuller sense.

The exception is “In the Second District.” I began toying with it as an undergraduate, overhauling it again and again, for nearly a decade. I tried many different perspectives, perhaps resisting the first-person voice, which is not my natural mode but ultimately suited the story. It’s funny, an ex-girlfriend read the book and told me she remembered certain images from the very first draft: the Chinese merchants measuring the bear’s gallbladder, the dogs boiling at the cave mouth. I write a first draft quickly, often in one go, then give it the Isaac Babel treatment over a number of years:

“The first version of a story is terrible. All in bits and pieces tied together with boring “like passages” as dry as old rope…It yaps at you. It’s clumsy, helpless, toothless. That’s where the real work begins. I go over each sentence time and time again. I start by cutting out all the words I can do without. Words are very sly. The rubbishy ones go into hiding.”

Actually, I wrote these stories at a great distance from West Virginia, in radically different landscapes. Most in an ugly, flood-ravaged, land-grant library in Iowa City. Others in Wyoming, Key West, and Provincetown, Massachusetts. But maybe I would have written the same stories sitting on a rock in Dolly Sods, playing the autochthon. Impossible to tell. I didn’t begin writing until I left the state. Next year I’ll be in Rome. I look forward to more cognitive dissonance.

I’d rather live in West Virginia than anywhere else, but like most of my generation, financial necessity drove me away. Which is a great shame. My family still has hundreds of acres of land. When I try to think of ways to live there, I’m flummoxed. In the other places I feel adrift, anonymous, without history.

TC: At the end of “Something You Can’t Live Without,” the narrative shifts somewhat and focuses on the way that the landscape changes over the decades that follow the story’s climax. What prompted that as a narrative conclusion? Did you always have that in mind, structurally speaking?

MNN: I did have that in mind, a leap forward through decades, following the decomposition of the drummer’s body, having it break apart and travel, letting the beasts scatter him, letting other people encounter his bones. I wanted to force the reader to reckon with the idea that the story never ends, not even with personal demise; the narrative leaves us behind; stories are minute rituals that prepare us for death. The land rolls on without us. The fields on fire. The maps burning with mold. The names we give lost. The buildings collapse. The closing of that story might be the most important passage I ever write. Which is odd, considering I did it at 24. It was the first story I finished for the book.

I’d rather take a risk and fall short than do conservative work.

At that particular time in my life, I was around people who would make silly pronouncements about what a short story must not do, must not be. “If your main character dies, the story just has to end. You have no point-of-view. By definition you can only tell a story through one character’s eyes.” Whatever. So I wanted to kill off the main character and let this disembodied voice roll out the last few pages, to defy these narrow confines. I often write in an omniscient mode, which has fallen out of fashion. I want a narrator that can go anywhere, perceive anything, indulge in prolepsis, reveal what the characters do not know. In this mode you’re writing without a net. Just willing up a world out of language, out of a handful of dust. If you write a stupid line, you can’t blame it on your poor marionettes. I’d rather take a risk and fall short than do conservative work. People tend to love or hate my writing. I’ve made peace with that. One esteemed novelist told me I should write for television, as he found my dialogue salvageable. But I don’t admire his work, either, so that rolled right off.

TC: “Something You Can’t Live Without” is one of a few stories in Allegheny Front set in a particular moment in the past. When you’re working on a historical story, do you generally begin with a moment and time and go from there?

MNN: Honestly, not at all. My stories are image-driven. I begin with visions that come floating up from my subconscious. In the case of “Something You Can’t Live Without,” the cave-bear’s skull imbedded in the rock, the man rubbing blood off his neck with a neck-tie, the shrieking cloud of passenger pigeons, and the twin boys holding dead foxes, one red, one gray. In “Mates,” for instance, I saw that eagle nailed to the barn siding like an emblem, something you would see on a flag or a coin. In “Natural Resources,” a bear rocking an abandoned washing machine.

This may be an unorthodox tack for a fiction writer. The story, for me, always begins with image, or, if not an image, a sentence, a scrap of phrase. My writing practice is the knitting of these disparate pieces together. All else comes later: character, setting, plot. I reason that if the visions haunt me, they must have some cryptic import. By stringing these images together, I build a narrative skeleton. I make no distinction between contemporary or historical stories. The time will cohere around the vision.

TC: Was there anything that you did while writing any of these stories that surprised you?

MNN: Yes, that a publisher took them and I signed the contract! My stories tend to be expansive, lush — this isn’t in tune with the zeitgeist. I had the pleasure of noticing that most editors who published my stories in magazine are poets, not fiction writers. I play better with poets. I’m unabashedly concerned with the textures and music of language.

Embrace messiness and difficulty, rather than trying to grab a coveted spot in next week’s New Yorker.

The slender tale well-told has never been my love. I’ve been told I’m a novelist masquerading as a short story writer, but now I reject that, as it implies there is a certain done thing. I like writers who are unruly and push at what short story can hold, can be. Eudora Welty. Babel. Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Mavis Gallant. James Salter. Ron Hansen. William Trevor. Annie Proulx. Faulkner. Primo Levi. Calvino. Cortázar. That said, when I wrote this book, I was purposefully trying out different modes and perspectives — I need that to hold my interest, some technical challenge goading me along like a splinter in my foot — and so “Mates” and “Telemetry” are the more classical, Chekhovian stories. Others expand. MFA-world has narrowed the idea of what the story can be. I’d like to see my generation blow it back open. Embrace messiness and difficulty, rather than trying to grab a coveted spot in next week’s New Yorker.

For me, the writer must be a stylist. This can take many forms. Mavis Gallant might not dazzle one as a Bellow does on the sentence level, but her paragraphs are so rich, supple, and alive. (In another fashion, Henry Green does it by creating a disconcerting web of language where the matter at hand is never quite discussed, where partial thoughts and sentences hang in midair.) I remember talking to another fisherman about “live water” in a trout stream — these transitional zones of conflicting currents where the very water seems a living thing. It can’t be explained, but it’s unmistakable, you know it when you see it. The same with good prose. You feel it even before your mind can articulate what makes the dead syllables come to life. Like the question in Ezekiel, asked in the valley of skeletons: “Son of man, can these bones live?” Yes. Living prose transcends setting, character, and the other workaday facets of fiction. You see this in writers like Evan S. Connell and Sam Lipsyte, Muriel Spark and Shirley Hazzard. Writers who do it on every page, rather than lucking into it. Before Cheever died, he said in a speech that “a good page of prose remains invincible.” No hyperbole. He believed that. It kept him alive through years when he shouldn’t have lived. It has meant the same to me.

TC: “Natural Resources” focuses mainly on a population of bears over time and their interaction with the humans who live nearby. How do you go about making a very dry subject into compelling fiction?

MNN: Oh gosh, I find interactions between humans and animals endlessly fascinating. I never thought it dry. In a place like West Virginia, where people hunt and fish and live close to the bone, animals fill out your world as there are so few people. I would lay in bed, wondering what the deer were doing up on the ridge. How the trout lived under ice. I still consider the world in this way. I live on Cape Cod, and the calendar of the year isn’t divided so much by the months as by the premonition of digging clams in winter, the return of the striped bass in spring, the time to jig for squid off the pier in high summer. All this to do with sustenance and light.

As in that story, we used to drive to the Clay County dump at night and watch the bears feed on garbage. We called it “the poor man’s safari.” Then a woman smeared her toddler’s hand in honey, so the bear would lick it off and give a good photo-op, but instead the bear took the kid’s hand off — and welfare took the kid.

Much of the book hinges on relationships between humans and animals. In contemporary America, we find animals bloodlessly shrink-wrapped in the grocery aisle, or we inflict Stockholm Syndrome on our pets and fetishize them. In my book as in my experience, the interaction is more immediate, without the filter of sentiment or the factory slaughter-house.

We prize the human perspective too much. I wanted to force the reader to think about the bears.

We prize the human perspective too much. I wanted to force the reader to think about the bears. Everyone seems to know the Bechdel Test, a concept I found fascinating and ingenious. So I wanted to create this other kind of test. Are the animals doing anything when people aren’t around? If so, what? Otherwise animals are merely props for humans. That is morally repugnant. Their lives have richness.

Also, in “Natural Resources” I wanted to write the type of story that has no discernible human characters, in terms of a single perspective, but wills up a world merely out of a disembodied voice, purely on language. Along with Borges, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings” and “The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World” served as models, but I wanted to take it further, describing change partly from the perspective of animals, valuing that, breaking away from the narrow human realism that mostly characterizes our stories.

TC: “Natural Resources” and “Gauley Season” make use of unorthodox points of view: second person and first person plural, respectively. How do you best find what works for a particular story?

MNN: I don’t really think of point of view — for me, it’s a shorthand concept, too reductive as it concerns the merely visual. I think of narrative consciousness, a certain stance/personality the narrator takes toward the world. So I don’t consider “Natural Resources” second person. It’s unyoked from viewpoint, singular or plural. I doubt Faulkner, Joyce, or Tolstoy ever thought of point of view. It’s a concept that the MFA world began stressing as a teaching tool, which I understand, but now writers take it seriously. In a common workshop setting a challenge is taken as deviation. “Strike one! You dipped into another character there!” Rules are anathema. There are no rules. This ain’t golf. “Throw away your mind,” as Dr. Vigil says in Under the Volcano. I try to do what feels right.

As I said, a set technical challenge sometimes pushes me on like a wind-up toy. Like, “This story won’t have dialogue.” Eudora Welty fascinates me because she has a natural ear for speech, perhaps her greatest gift, yet she’ll write a story like “First Love,” with the deaf-mute boy Joel Mayes as protagonist, and she’ll deny herself the ability to feature human speech because she wants to explore that aspect of the boy’s experience. I adore that. She’s taking a risk. She cut out her own tongue and wrote toward her weakness, toward the unknown.

TC: Dynamics related to class and education both play a large role in “Telemetry.” How do you best integrate aspects like these into the wider scope of a short story?

MNN: Americans have never been good at talking or writing about class. One ignores it, or one becomes didactic and thumbs Das Kapital like a lunatic. There are better models. For example, Isherwood’s Berlin Stories is all about class, but that’s not the first aspect that comes to mine when one thinks of the book, or even the tenth. The book wears that concern so lightly, but class informs every page, rippling there, like the shadowy light a swimming pool casts upon a ceiling. Shirley Hazzard’s Transit of Venus is a more direct treatment of class, but even so, it’s so nuanced and fleet-footed — that vision of villagers tossing Clement Attlee in effigy on the bonfire! You get it in a sentence or two, then Hazzard moves on, dropping it. So deft.

Henry Green wrote:

“Prose is not to be read aloud but to oneself alone at night, and it is not quick as poetry but rather a gathering web of insinuations which go further than names however shared can ever go. Prose should be a long intimacy between strangers with no direct appeal to what both may have known. It should slowly appeal to feelings unexpressed, it should in the end draw tears out of the stone.”

Amen.

Robert Stone’s Hall of Mirrors is another fine model, I think, from someone who knew the underside first-hand, the child of a schizophrenic, out of orphanages and Marist homes. Class is all, yet is never spoken aloud.

TC: What would you say that you’ve learned from writing these stories that you’ve been able to apply to your subsequent fiction?

MNN: Writing, for me, is thinking aloud about the world. A story is the fossil record of that thought. After that, I move on. You could say I’ve learned nothing. I don’t look back except to say that I’ll never have to write a story like “Something You Can’t Live Without” ever again. No point in doing the trick twice. Of course, in a commercial sense, the world craves that you do the same trick over and over, but dedicated artists — say, Joyce, Faulkner — tore down their art and made it anew in each book. But the temptation is there. You even see a great writer like Flannery O’Connor repeating in certain lesser stories, doing imitations of herself.

After Allegheny Front I may never write another story. I may write a thousand more. I don’t know. The snake sheds its skin. So now I’m looking for a new syntax.