Books & Culture

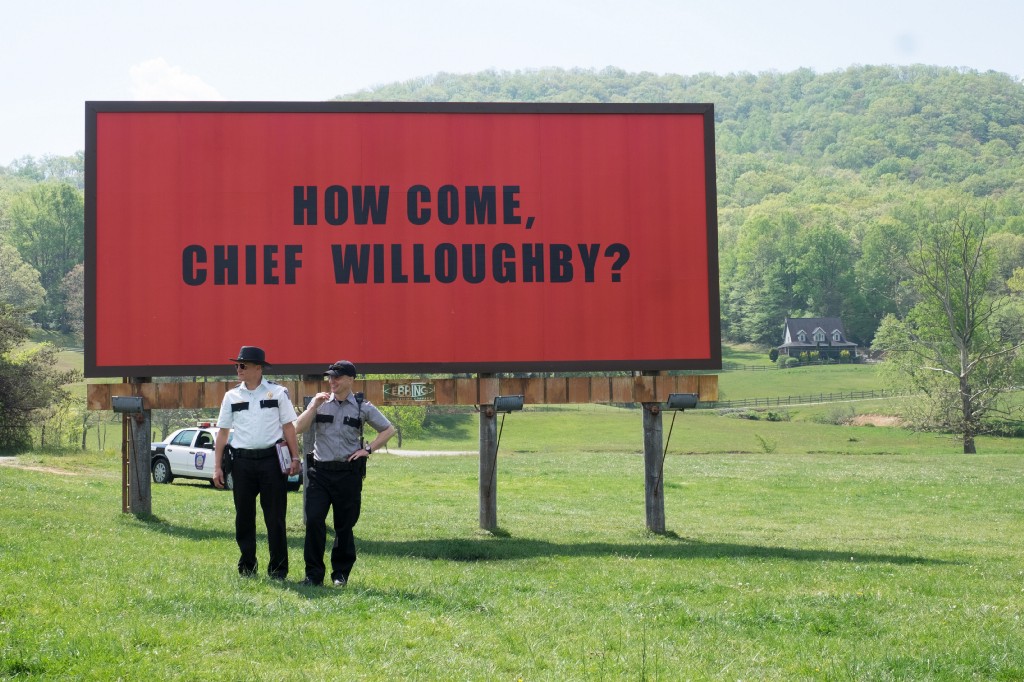

‘Three Billboards’ and the Way We Forgive Racist White Men

What it looks like when a film tries to redeem an unlikable character who might be irredeemable

O f nine Best Picture Oscar nominees for 2018, none have been so polarizing as Martin McDonagh’s Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017). Taking place in the rural south under the backdrop of its racial tension, Three Billboards has become the awards season’s poster child for its narrative mishandling, or downright abuse, of anti-Black racism, the spirit of the 2006 Best Picture-winner Crash reborn — another film that stoked ire for taking on race while failing to appropriately address it, and which gained subsequent success despite. As the light shone brighter on Three Billboards, it went from a film festival darling to a multiple Golden Globe and Screen Actors Guild Awards winner, and now a winner of two Academy Awards after being nominated for seven.

Criticism of Three Billboards is warranted: few Black people are included in a film which explicitly talks about racism in the rural south; Blacks end up portrayed as little more than props in a story that centers (white) victims of violence; a Black woman is thrown in jail, apparently in retaliation against the film’s white star, and is nearly forgotten there. In short, Black pain is the backdrop of a film largely unconcerned with it. But of the many justified gripes that Three Billboards has given rise to, the most insistent defense on the part of the film’s fans (and numerous award committees) revolves around a character named Dixon (Sam Rockwell, winning the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal) as the grievance that is least deserved. What this backlash reveals is not only who we are expected to sympathize with, but also how readily we offer forgiveness when it comes to racist white men.

Black pain is the backdrop of a film largely unconcerned with it.

Both criticisms and defenses of Dixon usually refer in some way to his “redemption arc.” A redemption arc is a specific type of storyline in which a morally repugnant character reveals the good inside them over the course of the narrative and ends up acting on their better selves, essentially paying an emotional restitution to the viewer and regaining their favor. You hated Jaime Lannister for pushing Bran Stark out of a tower, but you hate him less — or even come to like him — as he grows close to Brienne of Tarth, saves some characters’ lives, and protects King’s Landing. You hated Severus Snape at the beginning, only for his journey to lead you to care about him, despite what came before. The same, as applied in Three Billboards, looks like this: initially depicted as racist and violent, Dixon draws empathy from the viewer through a reveal of his sad home life with his verbally abusive mother, from his personal growth as he tries to become a better person, and as he helps Mildred find justice for her daughter.

The problem is that none of those things should change how we feel about a violent and racist character.

Viewers sympathetic of Dixon believe that he, by virtue of his attempt to change, pays an emotional price that is restitutive to the other characters, as well as to the viewers themselves. But none of Dixon’s acts are in relation to the violently racist portrayal that makes viewers hate him in the first place. While Dixon is shown to have a pathetic home life, that doesn’t begin to pay the moral or emotional cost of his racist violence. And while he tries to help Mildred find her daughter’s rapist and murderer, he ultimately fails. In the end Dixon accomplishes nothing, and helps no one. When it comes to restitution, he doesn’t actually pay.

A redemption arc requires a redemptive act or accomplishment, which begs recollection to 2006’s Best Picture winner, Crash. Widely lauded by many white critics to the chagrin of many Black ones, Crash features a racist cop (Matt Dillon) who sexually assaults a Black woman (Thandie Newton), but who, in the end, rescues her from a burning car. The movie’s theatrical poster famously includes the woman clutched to his chest, putting this narrative at the forefront out of all others in the ensemble film. Its message was cringingly clear as a racist-cop redemption arc — the character’s saving of a Black woman intended to reflect his deep-seated valuation of her life, which was only buried under the trauma of his own life experience (to say nothing of his failure to value her life when he molested her before).

Why We Love Women’s Revenge Narratives

It makes for a ripe comparison, Three Billboard’s Dixon standing alongside the racist, assaultive cop from Crash, except that from a narrative point of view the latter crosses the finish line to include what every redemption arc ultimately needs: a redemptive accomplishment. The result is Crash’s cringeworthy message and imagery, while Dixon in Three Billboards actually fails to accomplish anything at all.

Three Billboards ends in an uncomfortable place, treating with sympathy a character who remains undeserving, while expecting that the viewer will be endeared to a racist cop with no redemptive accomplishments and who achieves literally nothing positive. Those who do find Dixon sympathetic raise the question of whether his character arc is the problem, or whether such sympathy reveals an uncomfortable latitude in their feelings towards racists. The alternative is not to find Dixon sympathetic at all — to actually hold his character to the standard of redemptive accomplishment.

Those who do find Dixon sympathetic raise the question of whether his character arc is the problem, or whether such sympathy reveals an uncomfortable latitude in their feelings towards racists

To deploy the redemption arc loosely, as McDonagh has in Three Billboards, is to afford more credit than racists deserve. It presupposes that someone’s attempt to change is enough: that their positive intent is enough to outweigh their negative impact. Frankly, the price of Dixon’s redemption is so high that even if he had been successful in bringing down the film’s unseen murderer and rapist, its indirect relation to his racist past (and presumably racist present) would still be inadequate. The film sets the bar for redemption dishearteningly low, if we’re meant to see this racist white cop’s attempt to help a white woman as the sole requirement for him to be able to redeem himself. Worse, his character only succeeds in making Mildred more like him, as they both spiral deeper into unchecked violence and white vigilantism, failing to change the status quo. Familiar territory for a racist white police officer.

Three Billboards invites a lot of deserved criticism for its handling of racism, which will hopefully lead to more careful consideration among moviemakers who tread the same landscape in the future. But the questions it raises of who we sympathize with, and expect sympathy for, ask for self-reflection from us audience members, too.