interviews

Tommy Orange Gives Voice to Urban Native Americans

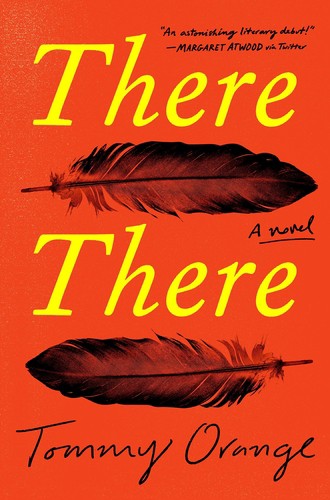

The author of Pulitzer Prize finalist "There There," on writing for a Native audience

Tommy Orange is the author of There There, a novel that circles the lives of Oakland, California-based urban Indians. Tommy’s work offers varied interpretations of Native life, culture and inherited trauma, lived in and through the city. He spoke to me thoughtfully about the potential social implications of his book, so needed right now for urban Natives — living too long as ghosts in the American city.

We grew up not far from one another. I am only an hour further east, inland to Stockton, California. Our cities were post-industrial mirrors of each other, similar in class, construction, and constitution. And our lives as singular urban Natives, separated from our culture but with our culture still swimming through our blood, were submerged in the wilderness of our cities, only ever able to blend in as biracial alone; until now, as we both work to write ourselves into existence within the structures of the cities we grew up in. With work like Tommy’s novel hitting the shelves of the mainstream, priming all urban Native writers to come, we will live as ghosts no longer.

This interview took place in Santa Fe, New Mexico during the graduation residency for the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), where Tommy is an alumnus and now faculty in the Creative Writing graduate department and I about to graduate with my MFA. We met in a high-end restaurant in the center of what is called The Plaza of downtown Santa Fe — an art district showcasing endless amounts of Native American art, authentic and not. It was happy hour in the restaurant and we were the only two non-white people in the place, the only Indians. We were put in a dark corner and ignored by our waitress and most of the staff, had to hunt down our waitress to finally get our check, and several attempts to flag down waiters ignored. A rush of stories ran through my head I had heard from IAIA peers and faculty about Indians being treated inhumanely in Santa Fe by the starkly white bourgeoisie, even as our art sells to these people for thousands upon thousands of dollars throughout their downtown boutiques. The irony of colonialist art appropriation practices never lost on us.

During the interview, though, Tommy and I pretended not to see the obvious — that we were the hidden Indians in the room, ignored against an all white space — so used to being treated as the ghosts we have been. Instead we focused on our work to be done, as always. We conducted our interview with much joy, conversation punctuated by laughter and our bright wide smiles, even as we sat in and spoke on the darkest parts of our historical past and present.

Marlena Gates: What is it to write about the violence and trauma of the Native in the modern sense, and how do you feel about the argument against the writing of Native life as harsh and cruel — a critique coming from inside our own Native literary community?

Tommy Orange: I’m writing to a Native audience and anybody from it knows that these are realities. I’m not making this stuff up based on nothing. It’s a grim, dark world and reality that we struggle through. I tried to have my characters transcend a lot of that stuff. They’re not bogged down by it or it doesn’t define them. I want to humanize all my characters and, sure, they experience things that are a part of our communities; but I wanted to flesh them out and have them experience joy and sadness like all humans do. One thing about Native people is that we’re turned into one dimensional people, a one dimensional thing; we’re a statistic or we’re a historical image. To make fully fleshed human characters represented in a big way, as something that gets distributed everywhere, does a lot of work to update people on what it means to be [Native], to just treat us like humans, know that we exist now, to just treat us like everybody else. We don’t get regular treatment. We are the minority of the minority. I don’t have any problems talking about the realities that we face.

MG: So making your Native representation all sunshiny bright and rainbows was not a priority?

As a reader I feel like I never read about people that I know, the people that struggle financially.

TO: Violence is such an ingrained part of our history but we’re never able to reconcile with it because people aren’t willing to admit that it was such an important piece of the conquering and the killing that has happened. We aren’t even willing to admit it, as a nation under Americans, and so there is this insidious violence. And there are other practices that aren’t direct violence that affect our lives based on policies. The thinking around us, and the erasure that’s happened, is a different kind of violence. So to represent that, as well as the real violence that happens, I liked.

MG: Then it actually humanizes the Native more to show clearly the dark side of their lived experience?

TO: I think so. That’s one of the functions of the novel — to build empathy for the reader. How do you do that? You have somebody go through an experience by having them walk in the shoes of the characters and fall in love with the characters and feel for them and you hope that that transfers somehow to real life. You hope.

MG: Tell me how you constructed your characters so real and true to life?

TO: I worked a lot with the Oakland Native population, at the Oakland Native American Health Center, but the characters were not pulled from any reality. I was not seeing people and thinking I could make a character based on them. The characters are from an imaginary Oakland. A lot of it was trying out a whole bunch of different characters, like an auditioning phase I called it, where I was just writing every day trying to write a new character, and whatever voice that felt like it would last and stick I would keep and develop those further. I created a lot of characters that I didn’t use and then after a distillation process I figured out which characters were most distinct and most essential to the narrative I wanted to write. There’s a spirit of the people of the Oakland Native community that I was channeling for every character.

MG: This book is getting so much visibility already, nationally and even internationally, with literary powerhouses such as Margaret Atwood calling it an “outstanding literary debut.” It will be read by large swaths of people and is already set to make a huge impact on the literary world as a new American genre. How is the average American reader going to benefit from understanding the plight of the urban Native in particular?

TO: My readership is for Native audiences, but you hope when you’re a writer you’re writing something that can connect to anybody. Not writing in a general way, but there’s this weird thing that the more specific you get the more universal you can be, for some reason, it doesn’t make sense but somehow it does. I think the idea of acclimating to a city environment is something that everyone has gone through. Also the way I frame environment through a Native lens has to do with understanding a way of life — to respect the “all your relations” thing. “All my relations” is a thing you hear in the Native community. It’s a way to have a relationship to your environment that gets to the cities too. It sort of counteracts this “connection to the land” Native trope, it’s a way to have connection to the land. Native people can have a connection to the city in the same way that you would any place. Like the way the sound of the freeway sounds like a river and how you can have that connection to it — a respect and love for the environment no matter where you’re at.

MG: All the urban Native characters of There There are a part of the American poor working class (PWC). In this way, through the details you map in your novel, could it then be an anchor for the PWC American to relate to the urban Native, finally, rather than continuing to see all Natives as mythic creatures in headdresses out on reservations somewhere?

TO: When you look at a lot of literature, if you do the numbers, the data, not only is it crazily white, but so much of the narratives have been upper middle class. As a reader I feel like I never read about people that I know, the people that struggle financially. A lot of the problems have been rich white people problems, and so getting the PWC onto the page was a big deal to me because I just didn’t see it. There was a gap. People do it more now, because there is a transformation happening in literature where representation is getting better. But for a long time you don’t get that many stories about people struggling. You got a lot of white privilege dramas about divorce in New York, or a college campus story.

Native people are turned into one-dimensional people, a one-dimensional thing; we’re a statistic or we’re a historical image.

MG: Can the urban Native genre as a whole help to transcend racial divides on the level of the poor, by creating a picture of the modern Native struggle in a real way, where Natives are right there alongside the PWC?

TO: I would hope so for sure. That’s an empathy connection building possibility. When you read about another culture, or another group of people who have another experience than you, but you can see yourself reflected in them anyway, it does a lot of work on your soul, on your brain. I’m a believer in the power of what books can do and what they’ve done for me.

MG: I can think of so many, but to you, what aspects of the book specifically break into that structural empathy building?

TO: Opal’s mother’s experience of domestic violence, the eviction notices they would pretend they didn’t see, riding the bus, everyone takes the bus. When you read a lot of novels people are driving everywhere, people are taking planes. When you go to an airport there’s a certain class of people at airports; poor people don’t fly. So I think a lot of the little details throughout the book connects people because I chose to have my characters living in this particular class.

MG: In many ways the Native American in general, living in America, surviving under so long a history of policies bent on destroying our bodies and cultures, is a walking contradiction just for existing. On the contradictions of the lived experience of the Native in America, outlined well in many moments across the stories in your book, in some ways are these cultural contradictions felt in the body of the urban Indian more than that of the reservation Indian?

TO: Yes. Reservation people will ask you where you’re from and if you say Oakland they will say “No, where are your people from?” even when some people go generations back in Oakland.

This goes back to the environment thing — what is your environment and what is your home and where do you belong? When you can make Oakland your home. Reservations aren’t home. That’s where we got moved to, shitty land. We got moved there because they thought it was shitty land, and then they found oil and they did more shitty things. So this idea of how to exist somewhere and feel like you belong and feel like it’s home is a contradiction because we feel misplaced.

A lot of Native families came on [the Indian Relocation Act], which had insidious reasons. But not everyone came because they got fooled. Some people were like, “I don’t want to live on the reservation, I want to live a new kind of life.” So I have a line in the book that says, “the city made us new and we made it ours.” It’s a contradiction to be from a people who are thought of to be historical and who live such a contemporary life, but 70 percent of Natives live in the city now.

We are thought of as historical, but 70 percent of Natives live in the city now.

So many people spend their time looking through glass, and around wires and cement, and that feels like a contradiction. You’re supposed to be Native yet you live in the city, and that’s most of us now. So it’s a contradiction we have to reckon with, and that’s part of the reason why I wanted to represent the urban Indian consciousness. Everyone has to reckon with this.

A lot of reservation Indians now live in cities, and their children probably will too. There’s not going to be some massive move back to reservations, so we have to forge a new identity that’s related to the city in a way that we bring cultural values and ways with us. We must leave behind some of this narrow-minded thinking on what it means to be Indian, because all this reservation identity based stuff didn’t exist before reservations, and what did it mean then? Reservation consciousness is an adaptation after removal, after being pushed there. Being Indian meant something totally different before reservations. So we can’t just refer back to reservations like we’ve been on reservations forever. We have to think of the new thing that we’re going to be. How are we going to remain Indian and not have to fall back on trope and tired stereotype? We have to make new ways.