Lit Mags

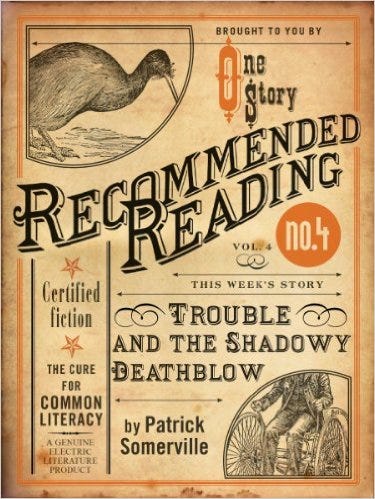

Trouble and the Shadowy Deathblow

by Patrick Somerville, recommended by One Story

EDITOR’S NOTE by Hannah Tinti

Here are some reasons why you should read “Trouble and the Shadowy Deathblow”:

• Spray-on cheese: Before this story was pulled from our slush-pile, I had never given much thought to the science of processed food. But after reading Patrick Somerville’s hilarious first sentence, and meeting artificial dairyman Jim Funkle, I knew that I had to publish “Trouble and the Shadowy Deathblow.” It appeared in One Story in October 2003. He had me at spray-on cheese.

• Star Trek: When I asked Patrick Somerville where the idea of this story came from, here’s what he said: “Well, I was living in San Francisco, and somebody on the BART sneezed on me, and I was incredibly angry about it. Then I went home and watched Star Trek. Worf was dealing with his son’s reluctance to enter into his rite of passage training, and he demonstrated some kind of ancient Klingon martial arts maneuver that I immediately imagined myself using on the sneezing man. Then I ate some Doritos.”

• The Deathblow: Sometimes I think about my life in two phases: Before I knew about the shadowy deathblow, and after I knew about the shadowy deathblow. I do not want to give away too much of this ingenious creation, but there is a spectacularly surprising sentence halfway through this story that involves the deathblow and a certain appendage. I still think about that sentence, whenever I believe I have written something smart and humorous. Is it as funny as that? I ask myself. Usually the answer is no.

• Patrick Somerville: “Trouble and the Shadowy Deathblow” was Patrick Somerville’s first publication. I still find this hard to believe, because the story is so good. In the nine years since we ran it in One Story, Patrick has become a literary rock star, publishing four books, including the just-released This Bright River. In its brief life this book has already received rave reviews and been part of a literary dust-up, which somehow resulted in a friendship between the novel’s fictional main character and a real-life editor from the New York Times. Only in the world of Patrick Somerville could something like this happen.

• Joy: One Story has published over 170 different authors. At this point, I am the only one who remembers them all. I have developed a knack for summarizing each story into a single sentence. Here is my sentence for “Trouble and the Shadowy Deathblow”: It’s about a guy who makes processed cheese and accidentally becomes a killing machine. Even though that sounds super awesome all on its own, this story is so much more. It’s about jealousy and fatherhood and marriage and self-worth. It’s about rage and mystery and ambition and secrets and crazy strangers who send their birds to peck out your eyes in the dark alleyways of San Francisco. It is written with great skill, humor and heart. But most important: there is joy on every page. You can tell Patrick Somerville had fun writing this story, and I promise: you will have fun reading it, too.

Hannah Tinti

Editor-in-chief, One Story

Trouble and the Shadowy Deathblow

Patrick Somerville

Share article

I HAD BEEN INVOLVED in pressurized and spray-on cheeses for over a decade. I would say that only three or four men in American gustatory industry — DeGrolun and Franklin unquestionably, Carmichael and Nussbaum perhaps — knew more than I did about the canning and containment processes of integrated synthetic cheeses. I spent six years at Frito-Lay and was independently contracted at Oscar Meyer during their mid-nineties run at the first pre-cooked cheese hotdog. I was there to provide information concerning the possible manipulations of ewe milk.

The project failed dramatically.

My name was removed from company records. My colleagues wouldn’t return my calls. The credit for my previous accomplishments with spray-on products went to other researchers. I was a pariah.

For a year I did independent specialty riboflavin work in my basement. I needed some time to pass and the hot dog trouble to blow over before I could look for a respectable job in the industry. Start over. Find something I could be interested in. Something that would allow me to respect myself again. I was forty-three, developing jowls, and had no idea how I’d gotten where I was. And where I was was not very interesting.

My wife Gina and I had gotten lucky with a few salmon investments during the boom and our savings had been carrying us through. If you’re married to Gina Funkle, however, you can only live off savings for so long. Our son Eric needed his toys and his trips to the dentist. Gina needed her flowers. Predictably, after Christmastime, when the tree was lying sideways in the snow in the front yard, she started riding me. Told me to get serious about finding a job. Anything. She was working down at Pranges in the mall, managing the jewelry department. She liked what she did. She had coworker friends who would come over to watch television, drink my sodas, and eat my potato chips. I stayed in my laboratory when they came.

I had heard of the National Food Sciences Convention (NFSC), teeming with interviewers and desperate food-industry lackeys like myself, and thought nothing of it while gainfully employed. But when Gina is on your case and breathing down your neck funny things start to happen to your mind. This is trouble, this alteration. The essence of trouble is the connection of the emotional and the rational. You make decisions you would not make under normal circumstances. If you saw Gina operating the vacuum cleaner when she wants you to do something, you would understand.

You can be sitting on the couch, reading a magazine, and she’ll come from around the corner at a near-run, cord in one hand, handle of the vacuum in the other, headed straight for your shins. If you’re lucky you get your feet up out of the way before she pins you down. I’m not very lucky.

“Going to the convention, Jim?” she yelled over the roar of the vacuum, the last time she’d caught me. The middle of April. She was leaning forward with her classic smile.

“You’re hurting me,” I yelled.

She pulled the vacuum back and slammed it against my shins again.

“I’m going to the convention,” I yelled.

I made the calls, paid the fees, and registered as a visitor. I was to be in San Francisco for three nights.

The evening before the trip I tried to play catch with Eric in the back yard but he insisted on wearing his glove on his head.

“Put the glove on right and field this grounder,” I said to him.

Eric is at heart a good boy with a sharp wit. There was a time, even that night, out in the yard, under the stars — Wisconsin can be a wonderful place — when I believed he would grow into a good man. Perhaps a strong man.

I don’t believe it anymore. He plays at life with too much of his heart. He’ll be eaten alive when he leaves the house. The world’s all locusts and people like Eric are corn. Strike one.

He’s thirteen and he doesn’t know how to tie his shoes properly. Strike two.

But strike three. Strike three is the real trouble. His cheese-man dad is a murderer.

I don’t travel much. Almost never. I took a shared shuttle from San Francisco International Airport to the Hotel Maribel, the site of the NFSC. The decrepit man who drove us didn’t write down any of the addresses, just nodded once at us all when we told him our destinations and snapped his neck to the next person in line. It was overcast, and he ran the wipers on the highway, although I never saw any raindrops. I thought to myself that perhaps this was something that they did in San Francisco. A mist-related superstition. He smoked like a Turk, and hunted for radio stations as we cruised up U.S. 101 amidst a sea of traffic. I sat with my hands in my lap and looked out the window, watching San Francisco approaching with all the glory of its whiteness, topography and excellent color coordination. I had never seen it before, save pictures of the Golden Gate Bridge or surly snapshots of the famous Beat Poets outside of the famous City Lights Book Store. We came over the crest of a hill and saw the condos lining the highest parts of the city, all lined up in unison, towering over the lower areas, where all the regular joes must have lived.

The shuttle dropped me off beneath the white and blue-striped awning of the Hotel Maribel on Valencia Avenue. I tipped the driver, and he pulled away without a word. Standing there with my bag, it finally started to rain. I stood and watched the squirming legs of a homeless man across the street, the rest of his body struggling beneath a piece of sodden cardboard. Then the flow of traffic came, honking and fighting, packed in like cattle being driven to the slaughterhouse.

I checked into my room. Heaven. Let me tell you. A long, open hall, a king-sized bed, a big tile-lined bathroom, and an old antique desk. Back at home I had checked off the most expensive room on the sign-up sheet, the type of room DeGrolun would have picked if he were coming. Not that he would ever come. DeGrolun is a masterpiece of humanity.

Inside of my briefcase, which I laid out on the bed, were my cheese folders and my spaceman pen which can write while inverted. I also had a package that had come to the house the week before, containing the schedule of events and a plastic badge with my name written across the front in bold black letters. I took a shower and then, wearing the Hotel Maribel bathrobe, I walked along the hallway practicing handshakes and 180-degree turns with the badge attached to my lapel, feeling extraordinary. At a conference like this you’ll be surprised by someone tapping on your shoulder, some hotshot rabbit who doesn’t have the time to walk around your body and approach you from the front, and a bad turn can literally destroy your career. It’s possible, for example, to knock a drink from somebody’s hand with your shoulder. Or to end up far too close to a strange man’s face, forcing several moments of uncomfortable homoeroticism. In either case you can kiss the job goodbye.

I went to the desk, crossed my legs, and dialed my home number. After three rings the sound of my own voice on the machine came through, and I was informed by myself that no one was home. After the beep I left a message telling Eric and Gina that I’d arrived safely and that everything was okay.

“A-okay,” I said, and frowned at myself in the mirror. I hung up the receiver and sat on the bed for a few minutes, looking at the cream wallpaper. The convention didn’t start until the next morning.

I decided to ride the trolley into Chinatown and make a vacation out of it. Become a better person. Polydimensional. I hung my suit in the closet, closed up my briefcase, locked up, and headed out, into the night. I boarded the first trolley I saw.

The rain had stopped, and I was relaxed, sitting with my legs crossed halfway to the back, studying a brochure I’d picked up in the hotel lobby: Night Tours of San Francisco: The Famous Zodiac Killer! The conductor stood like a sentry at the front of the trolley, one hand gripping the long steering stick and the other above his head, holding the rope that operated his chimes.

We came to a stop, and I heard a gravelly voice making curt demands at the front of the car. I looked and first saw this tall rabbit talking to the conductor, jabbering something and stabbing his finger around. He was a slob. Absolutely. The homeless in San Francisco!

There was a small piece of banana attached to his collar. He had curly hair and a greased handlebar mustache like the famous Milwaukee Brewers pitcher Rollie Fingers. As I watched him argue I compared him to myself — by that I mean our mutual standards of personal hygiene — in order to bolster my self-esteem. It was something I had come across when I was Eric’s age, a selective eye at the right times to get myself together and beneficially distort reality. If you collect the right people in your pocket during the day you end up, once you make it to bed, feeling like several million dollars.

Whatever the problem, the two worked it out, and finally the man pirouetted on the heel of one of his clownishly large shoes and sauntered down the aisle, holding the seats for support as the trolley jerked into motion. He leered at the people he passed, each in turn, as though we were in a Mexican prison and he was one bad hombre trolling for a new gringo (!) murder victim. I looked back down at my brochure. As he passed me he slowed, and I could feel him watching the side of my head, breathing heavily like a gorilla. I concentrated on a photograph.

He sat down behind me and immediately started to sneeze. As far as I know — and I’m no socialite — one sneeze in public is acceptable. Two, possibly even three. I thought of saying, “God bless you,” or something to that effect. But the sneezes kept coming, one after the other, and soon rather than trying to help I was sliding down in the seat to avoid the germ-cloud suspended over my head. These were uncovered sneezes. Uncovered. First to the left, then to the right, and then straight ahead. Particles landed on the back of my neck. The heavy scent of half-digested gin filled the trolley. And as if to punctuate his offenses, each time he exploded — and these were extremely explosive sneezes — he made an additional sharp barking noise which lingered below. Very inhuman. It was like riding to Chinatown with a wounded Pekinese. Which was sneezing.

I’d had enough. Why not? I thought. Why not become confrontational in public? I was a man, after all. A different man, in a way. A vacationing man. A polydimensional San Francisco Jim Funkle. Perhaps a more aggressive male attitude was exactly what the doctor had been ordering all along.

“Excuse me,” I said, turning to face him. I had never done a thing like it before but as I looked into his surprised eyes I felt a certain power.

He sneezed again, onto the window beside my head.

I looked at the particles of snot dripping down against the moving images of buildings and pedestrians, and then at him, frowning at me.

“What,” he said.

“You’re sneezing on me.”

“I am,” he said, “Minkowski.”

“I am not your Kleenex, whoever you are.” It was thrilling to say this.

“But I’ve caught a cold,” he said. I detected the traces of an elite New England accent.

“I have a conference tomorrow,” I said. “I can’t be sick.”

At this Minkowski raised his eyebrows sarcastically and leaned back in his seat. I figured it was the end of it and there’d be no more sneezing. I had won.

After I turned he unloaded on the back of my head.

I spun around, ready for anything. Minkowski had gotten to his feet, and by the time I turned back he was in the aisle beside me. The trolley was bouncing over a hill, slowing down, and Minkowski was leering down at me again, holding onto the back of my seat, sucking my power with his eyes. He was slightly crouched. I held my brochure tightly and prepared to be verbally abused.

“I have a message for you,” said Minkowski.

I waited. The trolley stopped. Minkowski glanced to the front, raised a knee, held it suspended in the air for what seemed an eternity, and finally, with a vicious snarl, stomped down onto my right foot with tremendous force.

I called out in pain and Minkowski, ignoring the damage he’d done, hurried to the front of the car and leapt from the top stair, off into the night, hands in his pockets, as though, despite his disregard for hygienic safety and his violent behavior, he wasn’t even feeling very bad. He may as well have kicked his heels together. I watched him glide away into the crowd as I held my foot, which now pulsed with sharp pain. Minkowski moved with the grace of a swan.

At the next stop I limped off of the trolley, very upset, and wandered the streets of Chinatown. Fog rolled in. Fog everywhere. That famous unbelievable San Francisco fog. I delved lamely into the nebulous streets, paying no attention to the shops or the lights or the sea of bodies passing me on both sides. I was furious. I limped. I feared for my 180-degree turn. I cursed his name and his mustache. Minkowski! The anger boiled inside of my stomach, bubbling up into my eyes and my ears, and shot jets of some acid body chemical down through my legs and my ankles. I found myself, after what I believe was a very a brief blackout induced by the pain, reeling against a brick wall, delirious, and saw in my mind images of Minkowski’s gaunt body prancing through an apple orchard wearing only cutoff denim overalls, and I wondered with a start whether his malevolent virus had penetrated my respiratory system and was coursing through my bloodstream at that very moment, incubating.

After some halfhearted anger-retching and some time spent at a bus stop bench beside an elderly woman dressed in black garbage bags my head cleared and I decided to go into a drugstore to look for vitamins and perhaps an Ace Bandage for my foot. The thought of the convention now, like this, humbled me. I had no room to give, none, and a sick man with a limp is not the man you’re going to hire to develop your Fleur du Maquis.

I went into a Walgreens. At the counter a young woman, perhaps a student, sat reading a magazine. A man in a wheelchair with his back turned to the door was in front of her, haggling with her over a candy-bar. There were birds sitting on both of his shoulders. I did my best to ignore them. This is San Francisco, I thought. Neither bird looked at me.

The lights were nearly white, and lit the drugstore in a dead incandescence. I limped down the abandoned aisles in time with the Muzak and found a section of special herbal teas and preventative vitamins. If you’re going to survive, I thought, you have to act. If you have a problem, you have to fix it.

“Cold?” said someone to my right. “You got a cold buddy?” I turned and saw the wheelchair man looking up at me. He’d rolled in under my radar. His birds, perched atop his round shoulders, watched me intensely.

“I’m not sure.”

His red t-shirt was torn to shreds, and his face was covered in a black patchy scruff. He wore a green army hat and a pair of loose, ill-fitting blue sweatpants. This was a diseased Fidel Castro in casual clothing. He had a concerned look on his blocky face. “Not sure?” he asked. “You either have one or you don’t, Mack. No in-betweenies.”

“A man on the trolley sneezed on me,” I said. I withheld the stomping information.

He nodded, as though approving. “The people in this town have no respect for tourists.”

“That is exactly how I felt at the time.”

“If you’ve got five bucks I might be able to help.”

“I don’t believe in panhandlers,” I said, trying, again, to sound like a violent man. I turned back to my vitamins.

“I’m not begging,” he said.

I looked at one of his birds. “Have your parrots been properly fed?” I demanded.

“These aren’t parrots,” he said. “They’re Buffon’s Macaws.”

“Are you looking after them well?” I asked. “Do you think they’ve had good lives?”

“I take good care of them, if that’s what you mean.”

“A tropical bird has an inordinately long lifespan.”

“I don’t need your advice.”

“I was making conversation.”

“The birds are my friends.”

“Well. Good luck with them.” It would have made a good moment to go to the counter and buy my vitamins and walk out of his life forever. Instead I stood and looked at the floor.

“I can see that you’re angry.” He sat perfectly still, watching me with gravity. I would like to emphasize as well the beadiness of his eyes. “I have a product for sale.”

I’m not one to wear my heart on my shoulder but Minkowski and his sneezing had thrown me for a loop. “I’m not angry,” I said.

He held out his hand. “The name’s Georgia.” He smiled for the first time, his lips curled, showing a set of teeth with more grime than the ceiling of Eric’s personal bathroom. “I sell solutions to anger problems.”

I shook the hand, then looked to the counter, at the girl, who wound an unending strand of blond hair around her finger. “You can’t be doing business in…someone else’s place of business,” I said quietly.

“You want revenge,” he said loudly, and pointed. “If you don’t get revenge you die on the inside. Everyone knows that.” He snickered, and the parrot on his right shoulder — blue — began to laugh at me.

This disabled man, Georgia, wherever he had come from, whatever mysterious swamp he had rolled out of, was not that far from the truth. I was livid about Minkowski. And maybe, in the same way that Gina’s glower can make me hop right out of my laboratory and take the car down to have the oil changed, this man’s persistent gaze was pushing me towards trouble. He had a strange charisma in the eyes. As well as the aforementioned beadiness.

“What’s the product?” I asked.

He whispered something.

“I didn’t hear you.”

“I said the shadowy deathblow,” he said loudly.

“I’ve never heard of it.”

“I don’t advertise.”

“What does it do?”

He squinted at the cashier, then back to me. “You can use it to kill a man.” He leaned forward from the wheelchair, towards my lap. “To kill a thousand men.” He paused, breathing heavily on the buckle of my belt. “It can never be traced back to you.”

Minkowsi lying dead in an open field. Minkowski’s body being lowered into the ground. Nobody at Minkowski’s funeral. A cremated Minkowski.

I realized that I was an amoral man.

I cleared my throat and attempted to look distracted. “Maybe I am interested after all,” I said. I took a box of tea from the shelf and started studying the label. “There’s someone with my name on him, if you know what I mean.” I peered at him sideways.

“This is perfect for you then.”

“How do you do it?”

“You take your arm back like this and you jab forward like this.”

“A stabbing motion with the arm.”

“I haven’t shown you all of it.”

“How much more could there be?”

“Five bucks’ worth.”

“And with this deathblow I can kill people and not get caught?”

“That’s right,” said the blue Buffon’s Macaw.

I signaled with my hand that I was interested.

“Are you interested?” asked Georgia.

I made the hand signal again.

“What are you doing?”

“Outside in the alley,” I muttered.

He rolled away down the aisle, and I went to the counter to purchase tea, vitamins, and an Ace Bandage. I mentioned to the girl behind the counter that I’d been sneezed on, and that I was from Wisconsin. She offered minimal commiseration.

Outside, in the alley behind the store, Georgia taught me the shadowy deathblow.

“Now don’t do anything stupid with it,” he said, after the lesson. “And don’t mention my name if you do.”

I handed him the money. “How many things can a person do with a shadowy deathblow?”

“I sell it to people to improve confidence,” he said, folding the bill and inserting it into his shirt pocket. He squinted and looked up at the sky. “Think of me like you’d think of a karate instructor.”

I frowned. “How do I know that it works?” I asked.

“It works.”

I watched a cat meander along some trashcans behind Georgia, its tail vertical. “Have you ever used it?” I asked.

“I used it on a buffalo once. Never on a person.”

“What happened to the buffalo?”

“It died.”

“Whose buffalo was this?”

“Just a buffalo walking down the street.”

“There’s a cat right there,” I said, and pointed to the cat. Georgia must have thought I was trying to use the deathblow on him, and he jumped in his chair and rolled backwards a few inches. The birds half-opened their wings to get their balance and slapped the sides of his head.

“Don’t make sudden movements around me,” he said. “Because of the birds.” He stroked their heads, one with each hand.

I walked around the wheelchair and knelt down a few feet from the cat. It turned and watched me. It rubbed its cheek up against a brick on the ground. I used the deathblow on its head and it died.

“I told you,” said Georgia.

We both looked down at the cat’s dead body.

“All that for five dollars.”

We shook hands — both careful not to use the deathblow on each other — and said goodbye. I walked back towards my hotel, into the famous North Beach Italian area. I had become omnipotent. I considered hunting Minkowski immediately, going back to the trolley stop and picking up the scent. Bursting into his cardboard box. Deathblowing him several times in the forehead.

But it could take all night to find him. More than all night. I needed to rest, to avoid the sickness. The Convention. Why was I in San Francisco, after all? Minkowski and his sneezing made me forget everything in the world that mattered.

I went back to the hotel, drank a cup of herbal tea, ate some of my vitamin tablets, and fell to sleep. I woke at the crack of dawn to no symptoms other than a mild sore throat and stiffness in the legs. I wrapped the foot. After two cups of tea, one thousand tentative jumping jacks, and two hundred and thirty squat thrusts, there was nothing, I felt, to prevent outright victory.

Nine-thirty in the morning and downstairs the convention was in full swing. Tables and booths, special displays of technology, free products for the most advanced food scientists, inflatable snacks hanging from the ceiling, video monitors the size of my living-room wall showing new processes from around the globe. And the people. A zoo. The hum of the living beehive. A crawling room of smiling lackeys. And I was one of them. Ready for anything. What would Gina think as I walked into the house and slapped the new contract down onto the kitchen table? With my name scribbled on the bottom? She would throw herself into my arms. Call me the master of Tillamook Cheddar. And Eric. Perhaps Eric would learn to enjoy my company.

People say it’s good to be in charge of a family. The goal, always, is to be in charge. To run things. In the family or in the office. But being in charge puts you in bad places, people forget. You can only make a bad decision if somebody is allowing you that decision in the first place. Think of the fools. The idiots of the world. The idiots can’t get into trouble. There’s no trouble for idiots. But us? You and me? Regular joes? We’re moving targets.

Throughout the morning I roamed and refused to commit myself. I executed three archetypal 180-degree turns with no foot complications whatsoever. I spent time in the frozen pizza area and spoke to a flavorist who was interested in what I could bring to her company. I played the zucchini video game, and when I was through I got back in line and played again. I gave awkward high-fives to other middle-aged men. I ducked, I scampered. I cast a web of control and illusion across the chaos of the place.

At about three o’clock, having just sampled an enriched carrot juice, a man who I’d worked with for six months just out of college approached me with a smile on his face. His name was Hunter Harris. He had enormous white teeth, an ovoid head, and was wearing a suit that cost more than my car.

“Funkle?” he asked, laughing. He slapped me on the shoulder. “Jim Funkle? That you?” He reached past me for a bottle of the carrot juice.

According to the nametag on my lapel, it was me.

“Hello Hunter,” I said.

“Didn’t recognize you behind that mustache.”

I wear a fashionably small and well-groomed mustache.

“I guess it’s not a surprise to see you here,” he sighed.

“No.”

“Where are you at these days?” he asked. “Oscar Meyer?”

“No,” I said. “That’s why I’m here. I’m looking for something new.”

“No shit?” he said, in a way that made me remember the extent to which I despised him. He had copulated with my secretary twice. A real lady’s man, Hunter Harris. He took a pull from the carrot juice and wiped his mouth with the sleeve of his jacket. “’Cause I’m looking for a food scientist.”

Personal contact, personal knowledge of expertise, looking to hire someone with my kind of experience. Harris and I had always been on friendly terms, despite his being more charismatic, intelligent, forthright and handsome.

“Who are you with?” I asked casually. I reached for another bottle of the carrot juice. I had some difficulty getting the cap off.

“Nabisco,” he said.

That’s about as good as you can get.

“Came in as an independent about six years ago. A hole opened up on the marketing side and I decided to change over and work that angle instead. What the fuck does it matter to me, right Funkle?” Hunter Harris the nihilist. He held up his now-empty bottle of the juice. “Very multifaceted product.” It was all salt to me but after a comment like that I felt compelled to drain the rest of mine as quickly as possible.

“Hung up the tongs?” I asked. This was food scientist humor.

“What do you mean by that?”

I set my carrot-juice bottle down on the table. “Just a little food scientist humor.”

“I’m out of the loop.”

“I didn’t mean to offend you.”

“Look. Are you interested?” he asked. “I want to leave knowing I have someone. Save me the trouble of drawing names from a hat.”

I pursed my lips and nodded. “I’m interested.”

“Tell me you’ll take it. I need to get the fuck out of San Francisco.” As he said this, an eight-foot sub-sandwich walked up to us and picked up a bottle of the carrot juice. Harris watched him suspiciously and sneered after he’d gone. “Why am I here?” he said tragically. He pulled a small leather wallet from his breast pocket and gave me a business card. “You like San Francisco, Funkle?”

I pursed my lips and nodded, looking down at the card. My ticket. “I like it,” I said. “Although last night — ”

“Fucking shithole,” he said, replacing the wallet. “The only place worse than San Francisco is the entire Bay Area taken as a whole. Either way I’m in it.” He was looking off vacantly, into the mass of moving bodies. “What ever happened with that hotdog fiasco up at Oscar Meyer?” he asked.

“Faulty equipment,” I said immediately. “Bad long-range planning.” I had scripted both of these lines on the airplane.

He nodded, and I was unsure if this meant that he believed me, that he didn’t, or that he didn’t care one way or the other.

And then I sneezed on him.

I didn’t have a chance to turn my head. It came too fast. I hardly knew that I was sneezing. The head went back, the lungs at a fast stutter filled themselves with air, and I blew. Or maybe the Minkowski in me blew? Because it certainly was the germs within me, not the Funkle within me. Six-hundred miles an hour, they say. My snot and saliva exploding in a conical pattern, coating Harris’s face. In the instant before his reaction I saw a vision of myself dying alone in a boxcar, drunk and emaciated, somewhere in southern Ohio. My dead body then rolled slowly towards the open door and fell out onto the tracks. It was sliced neatly in half by the caboose of the train.

“Funkle,” he said. He hadn’t moved, except for closing his eyes. “You’re a moron.”

I stood still, heard the echoing sounds of Minkowski’s laughter. I saw Gina leaving with Eric and becoming a successful entrepreneur. Meeting Hunter Harris in an airport bar. The two of them hitting it off. Eric achieving puberty.

Harris reached into his breast pocket and withdrew a monogrammed handkerchief. Wiping his face, he sighed, turned, and without a word, he walked away.

This was a problem. Quandary. I had the card, but possibly not the job. Did I have the job? I resisted the urge to call out after him, believing that if I did my voice would rise to the timbre of a six-year old schoolgirl. Instead I left the floor, entered the lobby, rode the elevator, walked down the hall, unlocked my door, and sat down on the bed. I saw my suitcase, a black Samsonite, open on the floor. It was my soul. Some of my socks were still inside. I thought of calling home. Instead I pulled myself together and took a shower. I spent the night rolling from side to side, tearing up the sheets of the bed, waking myself by sneezing. I dreamt that I had Minkowski’s mustache, and was selling encyclopedias door to door. At one of the houses, a dog, a tiny Pekinese, chased me through the yard, around and around in circles. As I ran I stabbed downward with the deathblow.

The cold was gone in the morning. The foot was healed. I felt better than I had in months. Of course I had the job, of course Harris would come through. He’d have taken the card from me if his offer was retracted, I reasoned. I’d made an escape, come out on the other side a stronger man. A Nabisco-man.

I pulled back the blinds and looked out at the sunlit financial district of San Francisco. It was early, but the streets were filled with moving bodies; people were already getting things done. The morning is the time when the Earth and living make sense, and there isn’t any other way it could be. Night’s the problem. You get tired. The chemistry is wrong without the sun shining on you. Trouble comes, you think poorly. What else is there to do? And which one is real, the morning or the night? I smiled at the glass, amazed that people do this, that this is their choice, that they walk and they work. It was what I did, too. I ordered breakfast and executed over two-thousand jumping jacks. I decided on a whim to cancel my squat thrusts.

My schedule told me that today, Saturday, was to be more of the same. The convention would be concluded at night with a dinner and a speech or two from the leading researchers. Instead of hitting the floor again I spent the day walking in San Francisco, feeling satisfied that having connected with Harris, I had accomplished my goals, and I could afford a quick run through the city. I went to the Museum of Modern Art, saw famous pieces of sculpture by the incomparable Yoko Ono, then rode the ferry to Alcatraz, surrounded by screaming children and young European tourists wearing Capri khaki pants like Gina wears on the weekends. A man’s hat blew off on our way back from the island, and a group of us on the deck solemnly watched it as the ferry continued on and left it there, floating in our wake. After most of the others had turned away — the man’s wife having patted him on the shoulder and he, with a carefree shrug, having laughed it off — I saw a seagull swoop down, pick the hat from the surface of the water, and carry it back towards the prison.

I had saved my good suit for the dinner. I preened more than I would have, again attached my nametag to the lapel of my jacket, and rode the elevator down. My table was at the back of the converted auditorium, which had become, since I’d been there last, an oversized dining room. I introduced myself to the others at the table and listened to their conversation, saying nothing and sipping my water. My well-honed groveling instincts had been suppressed in the wake of victory. I was now a Nabisco-man having dinner. We ordered, and the salads arrived.

I was looking around the room for Harris when the keynote speaker was introduced by a beaming blond in a green dress, standing at the podium and leaning into the microphone. He was described as a genius. A groundbreaker. A man who had revolutionized the industry, fusing the academic and the practical with unheard of feats of intellectual acrobatics. He was an accomplished flautist, and had, in his youth, done missionary work in the jungles of Uruguay. Saved children. I raised my eyebrows as I poured the dressing.

I stopped clapping when I saw who it was.

He walked out onto the stage holding both hands above his head, clasped together, smiling out at the roaring audience, wearing leather pants and a white cardigan.

The curly hair, the Rollie Fingers mustache. The clownishly large shoes.

He stood at the podium and waved with both hands. It took a full minute for the noise to die down. I sunk into my chair, set my fork in my salad, and felt acrid emotions being created in my stomach.

“He’s absolutely brilliant,” whispered someone at my table.

Minkowski’s speech started with the history of food science and with no transition whatsoever moved to Uruguay and a long, confused story about the people of his village, a crippled woman’s spirit of emotional survival, and an allusion to the more eclectic facets of South American shamanism. I looked around at the people in the room. Rapt. He then spoke about outer space and the possibility of receiving signals from extraterrestrial civilizations, alluding first to the Drake Equation and its controversial variables and then citing several statistics from an underground paper circulating amongst the Berkeley faculty concerning artificial intelligence and the defunct Soviet Space Program. He rendered successful jokes. He was a fearless public speaker. He quoted French philosophers with ease. The body motions he employed conveyed perfectly the subtle truths behind his structured and well-considered points. As he spoke I sank further and further into my chair, hating the man for his sneezing and his general excellence, and also developing a fear for my ignorance of his reputation. Why had I never heard of him? Had I somehow consistently missed the relevant articles in the journals? In all my work and at all the different offices had I been walking out of the room just before the conversation turned to Minkowski? Or worse, had people stopped talking about Minkowski when I walked into the room? Who was Minkowski? With a speech my history was recast as conspiracy. A shadowed hue. Sweat dripped down my arms, my back, and the inside of my thighs as my salad was quietly whisked away by the waiter, untouched. Minkowski continued. He introduced slides and diagrams, wielding a laser pointer for over twenty minutes. He questioned the relevance of Foucault. Called for the reemergence of humanists. And then, briskly, the lights dimmed. The spotlight focused. I heard the tinklings of a hidden pianist, recognized the discord of Thelonious Monk’s most important work. Papers were passed out to the awestruck audience. The finale. Several sonnets. A pause. Then, balling up all of his momentum and all of the energy of the room, a series of villanelles outlining his vision for what he called, “The ineffable future of riboflavin.” With this last line he hung his head in a dramatic silence.

Standing ovation. People screamed. A woman at a nearby table swooned and was caught by a passing waiter. Somebody threw a bouquet of flowers onto the stage. Minkowski knelt solemnly, picked up the flowers, and, with unflagging grace and a true sense for the aesthetic of the moment, kissed the red petals of the most prominent rose.

I went to the bathroom and vomited up what looked like everything I had eaten in San Francisco. With it came my heart and my stomach, perhaps parts of my brain. Also Gina and Eric. Because Gina and I fell in love young, very young. I remember the day, at a park in Wisconsin, her at the tennis courts and me in the woods with my vials and my lepidoptery textbook, retrieving her lost yellow ball, attempting to throw it back to her over the fence. I didn’t have the arm. She laughed. She had friends and wore white skirts. I was Jim Funkle. And I knew, as I went to the sink and wiped my mouth with the gritty edge of a paper towel, that I had always loved her much more than she loved me.

At the peak of my despair, at the bottom of my life, Minkowski burst through the door and walked across the bathroom.

He unzipped the fly on his leather pants at one of the urinals. He was the kind of man who urinated with his hands on the top of his head, leaning back onto his heels and looking up at the ceiling, whistling. I watched his image in the mirror, my heart racing, and then looked back at myself, at my round, red face, the beginnings of my jowls. My small mustache. This man would never respect me, never have the slightest interest in me, and never, in fact, know me. He could, with a flick of his wrist, buy or sell all the Jim Funkles (and even Hunter Harrises) of the food industry, and on a whim determine our collective fates. He was so powerful that he no longer needed to make decisions, let alone be aware of the people around him, let alone see anything like trouble. He was Minkowski. He was a god.

I walked up behind him and used the deathblow on the back of his head.

He crumpled satisfyingly onto the floor, urine still exiting his penis, only now it shot upward and arced onto his stomach. The penis was like a small white worm coming up from the cavernous fly. His eyes were open, looking up at the ceiling, when I left the bathroom.

There was an isolated foyer on the other side of the door, a small square room with a red carpet and a coat-rack, and unwisely I stopped there to consider the situation. Minkowski was lying dead, twenty feet away, and I had killed him. I turned back to look at the door, planning to conceal what I’d done. Then it occurred to me in a series of gruelingly calm thoughts, like minotaurs arriving at my door for a cocktail party, that it didn’t matter whether or not I was caught. It was possible, for example, that holding Gina was out of the question forever, that a bad dream, that lying in bed with her after a long day’s work…that I may one day accidentally kill my wife. Or my boy. I was standing in the middle of the room like this, the consummate hesitating, ruminating lackey, when I heard a roaring sneeze behind me.

I reacted robotically. The polished 180-degree turn brought me around to face the man. Before my rotation had come to a stop the deathblow was already moving forward, always forward, out from my torso, and landed with a dull thud on the flesh of the man’s neck. He fell to the floor like a sack of potatoes, dead. Hunter Harris.

Again it was as though I had done this all before, that this was only a minor hiccup in an otherwise successful convention. I took Harris by the feet and dragged him backwards into the bathroom, then, releasing the legs, I went to the door and locked it. I turned and absorbed the scene: two dead men on their backs, one with an exposed member. I considered playing the homosexual suicide pact angle. But no, I thought. Too dramatic. Too unexpected. Extremely suspicious. Not correct.

After a moment I again took Harris’s shiny patent leather shoes into my hands and dragged him, his arms now up behind his head as though he were cheering at a Frank Sinatra concert, into the far stall. He was much bigger than me but with a progression of volatile pulls, my back wedged between the toilet and the stall’s metal wall, I got him into a sitting position, put his pants down around his ankles, locked the door, and scrambled over the top.

Then Minkowski, the same operation, the same tugging. When I got him seated I stepped back and looked at him and saw that there was something wrong with his face. He was still leering. I realized this probably meant he’d been leering when I killed him. I closed his eyes with two fingers. I felt as though it was appropriate for him to have died in a moment of arrogance but now I saw that it was something else, perhaps even more chilling — his pale face had become the image of amused benevolence. Minkowski was the Buddha. He happily understood the worthlessness of all things, and as I stepped back in horror, he emitted pure sympathy, knowing and caring that I still struggled in the worldly realm. Minkowski the God wished me well. His apotheosis was complete!

I opened his pants and began to tug at them, to arrange them around his ankles in a way that looked believable for a man doing his business. I was beginning to feel the heat. The weight of the anxiety. And I was having trouble with the right pant leg. I got it down around his knees but as I leaned into it my hand, wet with perspiration, slipped off of the leather and shot down with inconceivable force onto my right shoe. Impossible force. I fell backwards onto the cold tile, halfway out of the stall, looking up at the ceiling.

I had deathblown my foot.

“Mercy me Jesus Christ,” I said. It was as though a small demon had bitten it off at the ankle.

I held on to the toilet paper dispenser and pulled myself up, shaking the leg. No good — the foot only dangled loosely. I thought of a trick I used to play with Eric. You push your middle finger down and stop just short of touching it to the bottom your palm. The last segment of the finger goes dead, and you can move it back and forth as though it’s not a part of you. Phantom Finger, I called it. The sensations were not dissimilar.

With one last look at Minkowski’s grin I closed the door, locked it, and pulled myself over the wall. The landing was somewhat difficult.

Moving awkwardly between the sinks and the urinal, I discovered that with my knee locked and leg held out at a forty-five degree angle, I could put a negligible amount of weight on the deceased foot, as though it were a cane of sorts, in order to initiate a potent hopping movement that served as a substitute for my customary walk. The process put maximal stress on my left quadriceps but I had very few options and someone had started to bang on the door.

“One moment!” I called.

I hopped to the sink and washed my hands.

More knocking.

“One moment please!” I called. I arranged my hair and hopped to the door. I took a breath. All was in order. I turned the lock, looked back over my shoulder, and pulled the handle.

“Why is the door locked?” asked the man standing in the open doorway.

“I’ve been urinating excessively,” I said, extemporizing.

He looked me up and down with crossed arms, nodding. “It’s a public bathroom,” he said, walking past me. “You can’t lock the door.” He was in a suit and looked to be generally important.

I nodded sheepishly. Play the social anxiety card, I told myself. Paxil Paxil! Present the visage of a man afraid to urinate in public.

“I sometimes grow uncomfortable in these situations,” I said. I attempted to chuckle. I held the door open and watched his back.

“I don’t care,” he said. He was at Minkowski’s urinal.

“I’m going now,” I said.

He didn’t respond.

Success! Out into the night! Explosively hopping down Mission Street! I was after Georgia; I had a plan. I was going to unlearn the deathblow. I saw my innocence, my untainted self, laid out before me, happily interacting with its family. As I entered Chinatown I saw rollercoasters and birthday parties. Trips to the zoo! Several trips to the zoo! It started to rain.

Georgia was not at the Walgreen’s. I questioned the girl behind the counter. She knew nothing. I hopped back into the street and peered into alleyways. I divvied out change and questioned the homeless: men with plastic flutes, men with shopping carts, a woman in army fatigues. A saturnine rabbit with a pancake birthmark informed me that tonight, extraterrestrials would arrive.

“San Francisco!” I raved, and thrust my hand into the air.

I found him and his winged entourage at The Embarcadero. I saw them from across the street, their backs to me, Georgia in his wheelchair with an umbrella mounted at the back and the birds huddled together, leaning on one another for support behind his head. The three looked to be contemplating the dark, choppy waters, the stretching piers, the rocking boats, and, further East, the glowing blob of Oakland. The Bay Bridge loomed high above us all.

“Georgia!” I cried. He craned around and saw me. The birds also looked. When I started across the street Georgia began to flee down the sidewalk.

“Stop!” I yelled, hopping.

He turned his head. “Leave me alone!” he yelled. I believe he then pressed a special button on his wheelchair and accelerated.

My memories now become shadowy themselves. Wet concrete, labyrinthine corners, head fakes, muscle cramps. Burning lungs. Hoarse screams. I threatened him as I ran; I threatened to kill him. He threatened to kill me. There would be no unlearning; there would be only bloodshed and death, an end to this rolling menace, this source of forbidden knowledge. I became resolute, and hungry for his life. How long could his battery last, after all? Around us the headlights of uncountable cars lit the chase. We moved very slowly. The rain soaked me, dripped down into my eyes. I remember stumbling but not falling. I remember Georgia piloting his wheelchair into a mailbox and losing his umbrella. I remember striking out with the deathblow and missing, and Georgia sailing away before me, always ahead, always extending his lead, especially on the hills. And then his yell, his arm thrust into the air, “Fly! Fly!” and at his command the Macaws bursting upward in unison like griffins, crying out to their beloved master, circling in tandem above us in the ecstasy of the hunt. What is living if not this, I thought, and they dove at me and pecked at my eyeballs, and I shot outward and upward with the deathblow, always hitting only air. I screamed after Georgia. The birds drove me down an alleyway, crying out again and again, and finally I stumbled and fell into garbage; the birds flew away; Georgia was lost to me forever.

Minkowski is gone. As well as Hunter Harris. My nonexistent career at Nabisco is also gone. My foot is dead. Gina believes I was involved in a tractor accident on Divisadero Street. I have hardly thought of riboflavin. I am working at a pharmacy by day. The homunculus of the pharmacy, actually, with a wooden cane and small pieces of half-melted taffy for children. People hand me their slips of paper, and I sort their pills in a metal dish. I notice all the colors, and wonder if there are sugar coatings. I chat about arthritis. The head pharmacist is named Eugene Carmichael, and he kissed Gina’s hand when they met. Last night, under the same Wisconsin stars, I considered teaching the deathblow to Eric.

I thought better of it. He has enough problems, and some rather unfortunate accidents have occurred, leaving a bitter taste in the back of my mouth, near the uvula. The mailman, for example, who died of a sudden heart attack on my front lawn. But how could the details be of use? There are no rodents in the Funkle home. I touch people carefully, and hug with my neck and torso. I continue holding my cane when it is no longer needed for support. Once, angry and lost on a lonely road near Wausau, I pulled over and murdered eight cows.

Every year, as a gesture of solidarity, the students of Berkeley organize a candlelight vigil for their fallen professor, singing his favorite songs and reciting the most famous segments of his autobiography to the weeping crowds. The family recently watched it on C-SPAN. I felt nothing. Eric devoured his Oreo Cookies. Gina turned to me and said, “That was when you were there, wasn’t it?” She snuggled against me. She’s proud that I have a job and a clean white coat. A steady income. She wants another baby. How can I tell her that she would be bearing something grotesque?

Minkowski Minkowski Minkowski! Shockwaves have rocked the very foundations of the food sciences! Because of Jim Funkle! Trouble!

“Gina,” I said to her, that night in bed. She was reading. She looked over at me from behind her glasses.

“Hm.”

“Gina,” I said. I needed to tell the truth.

“What?” she said.

And then I couldn’t speak. “Piled bodies,” was what I had wanted to say. I grunted and got out of the bed. She went back to reading her book. I took my cane from the corner of the room, hung it from my neck, and descended the stairs, holding my special railings. Again, the nighttime. Very close to midnight, the most famous of all the hours. There is nothing to help me at that hour. I went to the kitchen and turned on the light. I stood unmoving in the center of the room, my deceased foot sticking to the newly tiled floor. What I needed was a glass of milk. What I needed was to dust myself off and get back into the lab, to mix up some chemicals and to innovate. I needed a new idea. Anything.

Eric insisted on moving into the basement shortly after my return from San Francisco. For moments of creative passion, as well as arguments with Gina, I had installed a bathroom and a spare bedroom in the lab, and Eric now claimed that a young adolescent needed such private spaces for personal development. Something all to his own, in order to shore up self-worth. Eric is a talented orator, and he presented his case well. Of course Gina did not understand, but I had helped to push it through; a child like Eric needs to feel strong at least once in his life. Besides, I wasn’t using it.

I hobbled through the dim utility room and cracked open the door. Pure blackness. I flipped the light switch, but the bulb was burned out. Eric Funkle is no handyman. I considered calling down to him, asking him to meet me halfway up with a flashlight or a candle, but the lab was soundproof, so instead I planted my cane on the top step and gripped the rail. I raised up my lame foot. As I descended I recalled the late nights in that bedroom when the magical ideas would come, rolling over my half-conscious mind in mute waves: glowing milk, liquid pretzels, potato spread, strawberry sour cream. Now each night I slept deep and icy sleep next to Gina. When I closed my eyes and drifted off I left the Earth completely.

At the bottom, I caught my breath and smelled the basement’s must. I felt my way along the wall, through the dark, towards the tiny blinking lights of the lab’s hermetically sealed entrance. With luck it would be unlocked, and I’d flounder past the beakers to the bedroom. I’d rap once or twice at the door, and wish my boy sweet dreams.