interviews

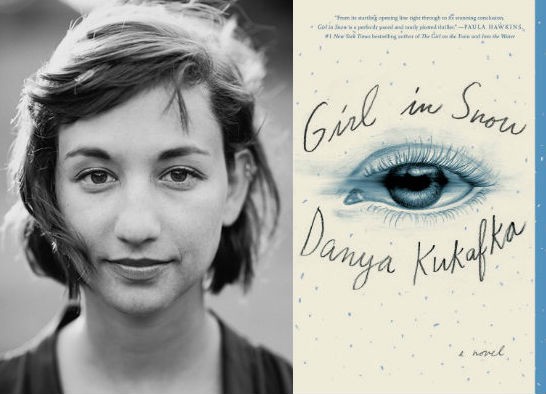

Upending the Small Town Murder Mystery

Danya Kukafka on small town tragedy, teenage angst, and pushing beyond the question of whodunit

Danya Kukafka’s debut novel, Girl in Snow, tells the story of what happens after 15-year-old Lucinda Hayes is found dead at a playground in her Colorado suburb. After the death is declared a murder, all eyes turn to Cameron Whitley, a loner who hardly knows Lucinda but spends his nights watching her and her family from their front yard and drawing portraits of Lucinda. Girl in Snow is made up of alternating chapters following Cameron, Jade Dixon-Burns, an angsty teen with an unexpected connection to the victim, and officer Russ Fletcher. The question that propels the narrative of Girl in Snow forward isn’t “Who killed Lucinda?” but “How will Lucinda’s death change the people she left behind?”

I spoke to Kukafka over email about how she played with the form of the murder-mystery novel, why she decided to focus in on these three characters, and her unpublished novels.

King: Obviously, your book is not the first murder-mystery book about the death of a beautiful, popular girl. I think one of the things that makes this book unique is that, yes, you’re reading to find out what happened to Lucinda Hayes, but as a reader I became equally invested in what will happen to Cameron, Jade, and Russ. How will Lucinda’s death affect the three of them? How is it changing them, how will it continue to change them? When you were writing and editing, were you cognizant of using certain genre tropes to your advantage, turning them on their head, in a way?

Kukafka: I was cognizant, yes, and I wanted to do something different. I decided very intentionally to stay on the periphery of the central event (Lucinda’s death), and to make sure that in the end, the story wasn’t about that. I never found the details of Lucinda’s death particularly interesting. I wanted to focus on the way death affects people, especially in small communities, and the things we learn about ourselves during disaster. But of course, there is a body, and in the end, there is a murderer. I knew I couldn’t leave the reader unsatisfied, so in that sense, I did decide to adhere to the tried and true structure.

King: Are you a big reader of murder-mystery novels (apologies for that phrase, which I think oversimplifies your books and many other books that get placed in that genre). If so, what are some of your favorites? What appeals to you about the form?

Kukafka: I am! Some of my favorite books are those that play with the form. Celeste Ng’s Everything I Never Told You is wonderful, because it uses a similar murder-mystery structure to talk about family, social class, and race. Megan Abbott’s books take teen lives seriously, and allow them to be ominous, dangerous. I love books that scramble the usual equation — The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold is one of my classic favorites, and so is The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides, and I even think Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro could fall in this category. I’m also a big fan of Gillian Flynn, Paula Hawkins and Emma Donohue.

King: I’d like to hear how you decided on the ending. When you were writing, was the ending changing? When you began, did you know how the story would end, what happened to Lucinda and how? Or did that reveal itself along the way?

Kukafka: I had a very hard time with the ending. When you set out to write a murder mystery where the murder doesn’t really matter, you trick yourself into thinking it will just work itself out, which isn’t true. The murderer was always the same person (except for a brief period at the very start where I thought maybe Lucinda’s mother did it, but that made no sense). I did a lot of intensive work with my editor to pull all the plot points together, and to make sure we were striking the right balance. At one point, there was too much information about the murderer, and at another, there was too little. A lot of work went into getting it right, keeping the focus on the main characters while also coming to a gratifying conclusion for the reader.

King: The setting seems so important in this book — and not just because of snow. When I was reading, I kept picturing everything in shades of white, blue, and smoke grey. Yes, probably because of the cover, but there’s also something about this story that seems like it has to take place in winter in Colorado. Why did you decide on Colorado for the setting?

Kukafka: Well, I grew up in Colorado — though I grew up in a city much bigger than the fictional Broomsville. Having lived in New York for seven years now, I realize when I go back to visit just how unsettling the landscape can be. On the front range of the Rocky Mountains, where Broomsville is supposed to be, you have these towering peaks on one side, with a sprinkling of suburbs tucked into the base. Then on the other side, you have miles of open plains. Moving away made me realize just how jarring this setting is, and also how beautiful.

King: Girl in Snow is being called your first novel, but am I correct that it’s only your first published novel? I’ve read that you wrote your first novel at age 16 and several thereafter. Are there parts of Girls in Snow in those novels? How do you think writing those unpublished novels at such a young gage helped you understand the form of the novel and develop a voice?

Kukafka: Alas, you are correct! I wrote a couple of very rough young adult novels before I began Girl in Snow. They were really different from my current work, though — they all contained paranormal elements, and they were absolutely of the young adult genre. They were also rejected by dozens of agents.

But they certainly helped me develop a voice, and to realize I wanted to write about teens, for an older audience. And they helped me understand just how much work goes into getting a novel to its final draft.

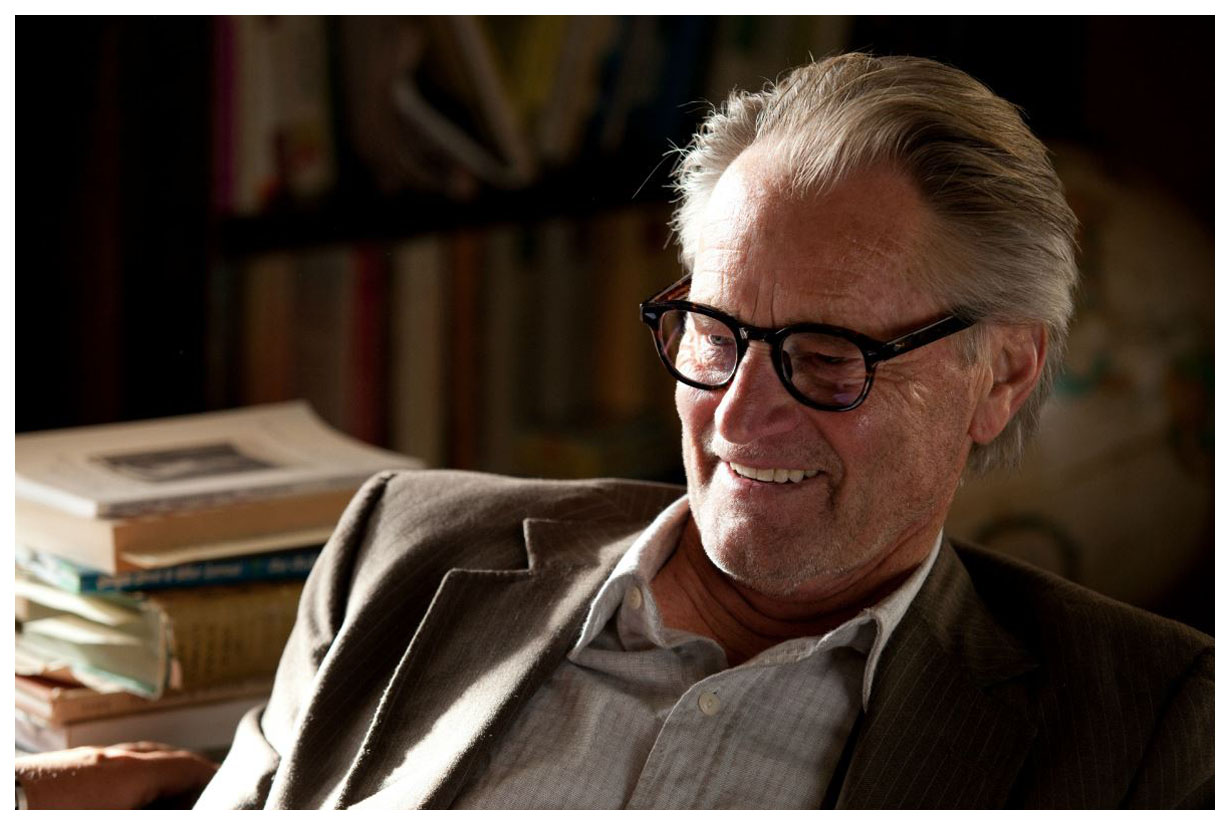

10 Great Vanishings in Literature: A Reading List from Idra Novey, Author of Ways to Disappear

King: Let’s talk about Cameron. if we didn’t get so much of the story from his perspective, the reader might be — to use a less than eloquent term — creeped out by him. But you allow us to understand the tenderness in Cameron’s obsession, and so much of his personality can be explained by what happened to his father. How did you go about developing his character?

Kukafka: I went into this novel wondering: can you be a good person, and still do something bad? I’m curious about people who commit atrocious crimes, what gets them to that point, and whether they do these things with a level of awareness. How do you reckon with that? Cameron, of course, is only slightly creepy, but I set out to create a character who could do questionable things, and still be lovable. I was also interested in his personal trauma, and how that can manifest, especially in the mind of a fourteen-year-old. Cameron is always straddling that line. His age, his psychological past, and even the little things that make him “not normal” all allowed me to work with a sense of unreliability, which I loved.

“I’m curious about people who commit atrocious crimes, what gets them to that point, and whether they do these things with a level of awareness. How do you reckon with that?”

King: Both Russ and Cameron’s chapters are told in close third-person, but Jade’s chapters are in first-person. Can you tell me about this decision?

Kukafka: Everything is immediate and explosive for Jade, and the first-person just felt right for her. She’s a teenage girl — her emotions are her life, and she experiences the world viscerally, always looking for meaning. First-person felt closer, and more volatile, which was perfect for Jade.

I chose the third person for Cameron because it allowed me to hold certain things back; what he may or may not suspect about himself. I don’t think he understands himself well enough to narrate his own life in the first person, and the same goes for Russ.

King: Okay, last question. What books are you reading now that you’re excited about?

Kukafka: I recently read Chemistry, by Weike Wang, which I loved, and I also really enjoyed What We Lose by Zinzi Clemmons. Lately I’ve been on a bit of a galley kick — two upcoming books I’m excited about are Red Clocks by Leni Zumas, and Back Talk, a short story collection by Danielle Lazarin (both come out in early 2018). I also finally read The Secret History, by Donna Tartt. I know I’m very late to that party, but I’m glad I showed up eventually.