news

Ursula K. Le Guin‘s Folk/Electronica Album Can Teach Us a Lot About Storytelling

Le Guin’s soundtrack for her novel ‘Always Coming Home’ has been praised as a piece of music. But is it any good at telling a story?

I n tandem with the release of her 1985 ethnographic tome of a novel, Always Coming Home, beloved science fiction and fantasy novelist Ursula K. Le Guin put out a cassette tape called Music and Poetry of the Kesh. The album, made in partnership with the composer and analog synth specialist Todd Barton, was conceived as a kind of soundtrack to the novel. Music and Poetry of the Kesh has just been reissued, and reviewers at The Guardian and Pitchfork agree: Le Guin and Barton dropped the most fire indigenous folk music/electronica/new age/avant-garde album of 1985. But here at Electric Lit, we’re more interested in literary value than musical chops. We wanted to know: Is the album any good at telling a story?

Le Guin’s novel Always Coming Home tells the story of the Kesh, a tribal civilization of people living in a California of the future, after an apocalypse so far in the past nobody can really remember it. Part of the novel tells the life story of a woman named Stone Telling, but it is also a giant assemblage of poems, maps, artwork, anthropological texts, plays, and music that illustrate Le Guin’s ability to make up a whole new world and its archive all at once.

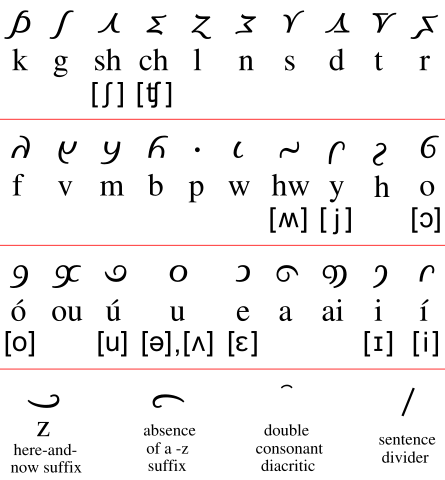

According to Pitchfork, Barton was onboard for world-building in the album, too. He designed instruments that Le Guin and Barton imagined the Kesh people would use, like a seven-feet long houmbúta horn, or a flute made out of bone. When Barton asked Le Guin if the Kesh spoke English, Le Guin made up an alphabet for the Kesh and used that vocabulary for the songs and spoken-word poems. The project took two years to complete.

In a word, the experience of listening to Music and Poetry of the Kesh is immersive. The album opens with the song “Heron Dance” a slightly discordant and mysterious pile of clatter, with high synth-y sounds that break into a rhythm that helps translate the sound into something like narrative. Listening to “Heron Dance” echoes the experience of reading the first few pages of a novel, when you’re trying to get your bearings in a new world built by someone else’s language in an unfamiliar setting, and figuring out if you want to stick around.

The first song echoes the experience of reading the first few pages of a novel, when you’re trying to get your bearings in a new world.

The pacing gracefully picks up in “Twilight Song,” when we hear Le Guin speaking in Kesh. Behind her voice, there’s suddenly depth — crickets, a babbling brook, and a breeze (which were all recorded on Le Guin’s ranch in the Napa Valley). Then, we learn to listen deeper in the space of the album, and are rewarded with more voices. We move closer to the voices somewhere in front of us in “Yes — Singing” and suddenly we’re at the center of a community of men and women singing, clapping, dancing, laughing. Many of the songs sound like they are heavily influenced by indigenous music, and at times I wondered how much the music brushes up against cultural appropriation. The culture of the Kesh may be her own creation, but Le Guin’s relationship to indigenous tradition was inherited from her parents, both cultural anthropologists who spent much of their lives studying and working with the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest.

But to return to our original question — how does the album stand as an act of storytelling? On its own, the music tells a different story than the narrative of Always Coming Home — one that’s much more abstract, a story about listening wide and long, about how community accumulates, about the act of listening as an act of imagination. You won’t pull off your headphones with a concrete cast of characters, or plot, or setting. But listening to the album alone does illuminate other elements that make for good storytelling: how to build atmosphere out of disparate details, how to create dimension by building tension between what’s up close and what’s far away, how to balance monologue and dialogue. Reading the novel alone without the album will still give you a complete story—but once you’ve heard the album, you realize it may not be the complete story. Together, the novel and album also enhance and play off each other to create a new story, a dynamic, totally immersive experience of imagination, where suddenly the story is taking shape in several voices: those on the page and those on the tracks. It’s a serious exercise for your imagination that makes me think of Le Guin’s words on how we build imagination in the first place.

Together, the novel and album enhance and play off each other to create a new story, a dynamic, totally immersive experience of imagination.

In her 2002 lecture titled “Operating Instructions,” Ursula K. Le Guin argued that imagination was not a given, but something we learn by way of the people around us. It starts, she argues, with listening: “Listening is an act of community, which takes space, time, and silence. Reading is a means of listening.” With Music and Poetry of the Kesh, Le Guin seems to suggest that listening is a means of reading, too.