interviews

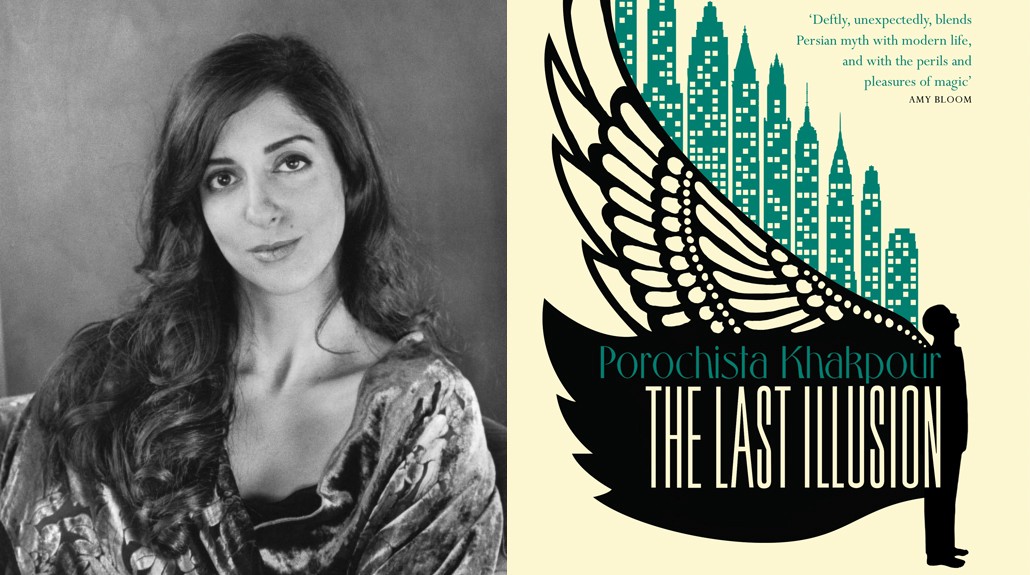

Us Against the End: an interview with Porochista Khakpour, author of The Last Illusion

I don’t remember how I first heard of Porochista Khakpour or her second novel, The Last Illusion, which was released in paperback this month, but I’m fairly confident it was social media’s fault. Usually how this sort of thing happens to me these days is I see a friend post something and a book cover catches my eye. Then I look into the book and if it sounds like I’ll enjoy it, I put it on my ever-growing wish list of books.

For Christmas my wife bought me a signed hardback of The Last Illusion, having seen it on my wish list, and I consumed the book in a way I hadn’t consumed a book in years: I savored it. I read it slowly, trying desperately to draw it out. I haven’t been so excited about a book in a long long time and it inspired me to want to do something else I haven’t done in too long: interview someone.

I reached out to Porochista through Twitter, where she has become one of the few people whose tweets I actually try not to miss, and she was kind enough to indulge my questions via email.

Ryan W. Bradley: The Last Illusion has a beautiful balance between the nostalgia of storytelling and a very modern plot and setting. It is easier to screw up trying to meld such disparate worlds of story than it is to nail it because consistency becomes so important in the voice of the narrative. Were there ever moments where you had to cut things out of the story purely because they worked against that balance?

Porochista Khakpour: I originally imagined something like The Wild Palms, one of the first Faulkner novels I fell in love with. I imagined two separate stories in alternating chapters. I imagined their call and response as subtle. But then as I got deeper into the draft I realized the two stories were very much the same one, that they needed each other, that their friction would create something interesting. It was a problem-solving challenge at that point. By the next few drafts, the relationship between Zal and Silber, man and bird, Y2K and 9/11, ancient Persia and modern-day NYC — it was all there, the connections. A mash-up is only successful if it’s a little bit surprising to the creator too, I think — that can be contagious to those on the other end. But it can’t just be a trick either — I don’t think either story could stand on its own, not the way I wanted it. The satiric, the surreal, the stylized — these were important to me not just ambiently but thematically. I wanted to create something altogether new mainly because the story made a move like that necessary.

RWB: You talk about friction between stories and that propels much of the plot, but the friction I found most interesting throughout was that within Zal. There’s the man and bird dichotomy, but I think it goes a lot deeper than that. You have mentioned in other interviews how you tend to write male characters, and in at least one from after your first book came out you mentioned trying to write more female characters. Zal takes a much more complex role than a male or female, he is an outsider to gender, and even humanity in a way. He has been told what he is supposed to be in his life, first by his mother, then by Hendricks and his therapist. But as he strikes out on his own he starts to find some ownership of manhood, it becomes a sort of discovery. He goes through layers of identification. It’s really intriguing. How do you see Zal’s flexibility in this process in the context of how he is or isn’t able to relate to the other characters, and do you think the complexity of his gender blank slate and self-discovery has changed the way you approach writing male or female characters?

PK: Very interesting question. This comes at the end of a hard day, when I’m trying to do everything I can not to cry and give up, but let me take a stab at it. I’ve always been interested in coming of age — Karen Russell and I were speaking about this at the Lannan talk we just gave and she was paraphrasing Antonya Nelson in part and saying that she loves coming of age as a subject because we never stop coming of age. For adults, this quest is still very real — to inhabit that idea of a whole person in us. I wanted coming of age, coming of human, coming of manhood, all to be here in different and similar ways. Is masculinity a metaphor? I want to snort a bit at my own question, but in a way it has been for me — maybe virility, or what the Chinese might call “yang energy.” I do find the worst parts of the stereotypically male — some archetypal straight white male for example — to be very interesting — partially because it’s rather easy to trace all the problems in this world to it, wars, genocides, homicides, you name it. Male energy, hate it or hate it, it has been historically a dynamic force in the world. Is it simply the hormone testosterone? Is it the idea of manhood? Is it the physical body of the male, what it implies, the negative space it requires? And yet aren’t men the ultimate underdogs in the end? We even outlive them, always have! On another level though, I was a bit of a tomboy and very inspired by my father and brother, and men I was friends with — again inspired is a strange word for me, because their shortcomings and mishaps were in their own way inspiring. Look at all that foolishness, and yet they survive! I think my first novel deals with men much more directly. Here I wanted to look more closely at the asexual and the pansexual, and so, yes, in a way it made me challenge what I thought of as male or female. But everything in this book is stylized, satiric, a bit animated in my mind. So it’s never quite that simple. This book can’t quite change what I think of anything — can any book really? maybe — because its universe is its universe. It’s not ours. The book is a retelling, on several tracks.

RWB: Whoever convinced us that we ever stop coming of age did humanity a disservice.

Survival is another strong thread in the book, and not just with Zal and his journey from bird to man. Hendricks is clinging to Zal in an effort to survive the loss of his wife, Silber is clinging to his reputation, Asiya is clinging to anything she can to survive the tempest of her visions and emotions. Human survival is at the forefront of my interests as a writer, and I loved seeing this swirl of frailty throughout your book. Ultimately the book blooms into a sort of 9/11 fable, which provides a wide lens on the same topic. What drives you, personally, to explore particular themes and do you think there’s something to be learned about ourselves or humanity at large by plumbing aspects of primal nature like survival?

PK: Your questions are so beautifully worded and intelligently thought out, I feel like a bit like an idiot before them. There are two ways to approach this question for me. One is a sort of autobiographical cheat: many of my friends and lovers have commented on how I am often preoccupied with life on a very basic survival level. I guess I know what they mean. I am a pretty good person in emergencies — maybe my best self then — it’s like all my life I wait for those moments to be truly me! I become calm, rational, a good leader when usually I’m a distracted goofy follower at best. Anyway I do think of life in terms of food-clothes-shelter and I wonder how much of that is New York, a place nobody can quite survive in and yet we somehow do. I also think it might have had to do with so many heavy survival challenges as a child — first memories all war and revolution, the uprooting, the looking for a new home, the setting in the US and then struggling to survive without a grasp on the language and then being forced to rapidly master it — the playground was such a daunting place for this little immigrant. And then so many awful life events, like 9/11. I think everything we do goes back to basic survival and I get made fun of at times for always saying things like, well, is it going to kill you? No? Then do it? Or what’s the worst that can happen, you die? And really that is all there is. Us against that, our end, the thing that we can’t survive.

I have a more theoretical answer but perhaps that’s the most honest. Writing is a performance and sometimes we answer as critics but you are a much better reader than I am — the best thing I can do is tell you where my impulse was, I suppose. But what a day to talk about survival — the city is all ice and I’ve taken three bad falls and I’m all bruises and cuts, and I keep thinking how crazy that this can kill you, or that choking on a sandwich like the great Mama Cass, how radical our fragility is indeed…

RWB: I’m just trying to do justice to you and the book!

I love when someone finds the best of themselves in difficult situations. There’s something truly amazing when everything goes wrong and you feel suddenly slowed down, calm, and think to yourself, “I’ve got this.”

You mention death, and like you said, it seems like it’s always the smallest things that hit us, make us think “so this is how I’m going to go.” My nearest-death experience was choking on a bagel and that was exactly what I thought to myself.

People often call death the great motivator. But it seems you and I are alike in our view of death, that it’s the worst that can happen, and eventually it will. For everyone. Do you think death motivates you? And how do you see it playing a role in your writing, because as a reader I didn’t once find myself thinking about death in The Last Illusion, everything to me seemed like it was focused on perseverance?

PK: Okay! Death! I made it through a cancer scare yesterday — had some bad news from a doctor that turned into good news — so I’m feeling bold. I am obsessed with death — it’s a big part of my everything. Was it Dali who speaks of Lorca practicing his “death face?” The Spanish obsession with death is not unlike the Persian one. I am so hooked on the great Sadegh Hedayat of Iran and his 1937 surrealist masterpiece The Blind Owl, which I got to write the intro to in 2011 (Grove put out a new edition of the English translation) — so much of my feelings about death and creation are tied into the nightmares of that book. But I am most obsessed with death because I am most obsessed with staying alive — and that is in the psyche of all the characters of The Last Illusion too. The end is coming — a sort of end is coming anyway — and what can we do but try desperately to live? The book is very anti-nature in some sense, very much pro-civilization. The City is everything, it IS the cosmos. The rural, or the village of the first chapter, is almost to me a paradise lost — I meant those sections to seem a bit unreal — the rural and the ethnic-specific there where everything went wrong, where everything could have gone to death, where myth meets a sort of nightmare of invisibility. But The City is where everything is laid bare, where all of life’s theater plays out. It’s shorthand for the world, of course — even all our nicknames for New York, “the Greatest City” all of that. The horrors of symbolism made literal — it’s all over the 9/11 narrative, the hijackers very intentionally created that. Symbolism and spectacle, so many of the seductions and tools of the artist now turned material, literal, organic — how horrifying it can be. What is metaphor and what is not, in our manmade world, all the déjà vu, the Baader-Meinhof phenomena, the cult of social media and its own superstitions and mysticism like the recent popularity of mercury retrograde, for example — well, I became obsessed with the magical thinking of our contemporary world as I wrote this, starting from the numerological delirium of Y2K. But we do these things, I think, out of a great fear of dying. With religion too, we fashion the god that we’d most want: forgiving, benevolent, a stern caretaker but caretaker nonetheless. But we fear its power and therefore want its power. Even the suicide bomber martyr I think is some ways marries himself to death, because it can’t live with death making the first move — that’s a sort of laughable way to put it perhaps, but I think of the power-hungriness of suicide, the need to take control. It’s maddening to not understand our ends, to not even experience them consciously in the end — how are we not tempted daily to just submit to it, to stop the horrible waiting? I realize I am a particular kind of dark bird, so many probably won’t relate to this, but this is where my mind goes, all the time. The basis of optimism is sheer terror, goes the famous Oscar Wilde saying, and I think that’s there in my book, in everything I do and write. We make the best of things, but we wouldn’t have to do if we were deep in truly the best. I learned we died older than most — I thought death by natural causes was impossible and you just kept getting old (let’s face it, some old people look several centuries old!) — and so maybe I am just trapped in that late realization. It makes people a bit nervous when I speak about it, so I try not to, but I think this “problem” is there, here, all the time. It shouldn’t paralyze us, of course, but I’d also say, what a miracle that it doesn’t!

RWB: I’m so glad you got good news! I had one of those scares a few years ago. It’s so otherworldly, the experience of waiting for the results. And even when you get good ones, there’s this weird internal emptiness, almost like crying it out, where you’ve spent so much energy preparing for the worst that you’ve emotionally bankrupted yourself.

In my research for this interview, I actually came upon the edition of The Blind Owl you wrote the intro for and instantly put it on my Amazon wish list (a great way to keep track of all the books, movies, and music I want to buy when (if) I have money).

I want to focus on the ideas of optimism and fear. I find your learning about natural death later in life interesting, because I don’t remember when I first became aware of death. On any level. I remember people in the family dying, but I was old enough by that point that surely I was aware of it beforehand.

For a lot of people death is the ultimate elephant in the room, especially for artists. So, if optimism and fear go hand in hand, how do they show themselves in your writing? What fears do you have that get translated into your writing, whether concretely becoming themes, or just in how you approach your work, being a writer, working on novels, etc.?

PK: Okay, where were we? So much has happened. Feb 12 was the one-year anniversary of the death of my friend Maggie Estep — which I’d been dreading for weeks — and then suddenly David Carr died that evening (I didn’t know him well, but I had hung out with him at events and parties and such). He was also an idol of mine though. I loved his memoir, and I love his work and just his presence around town. So gutting. And the Chapel Hill shooting, my god, the discussion around that. And many of my friends are seriously ill plus it looks like I may be having a sort of Lyme relapse (as I seem to do every winter). Oh, and I have an ex who has tried to take over months of my life with all sorts of messes. And the snow won’t stop. Last winter seemed to be The Worst Winter Ever in NYC, and now it has a rival. It’s Valentine’s Day and I’m neck-deep in deadlines, student neuroses, a bored dog, a house that is so unlivable that I basically can’t stop thinking thoughts like, what if I just threw away all the dishes and lived on paper plates and plastic utensils ’til this period blows over? This period! I don’t know if every late winter was as bad as these past two, but I’m now becoming phobic of winter, my second favorite season (autumn of course is first). Have I always been this unhappy? I have to remind myself that I have been much unhappier.

Death! Oh god, where were we? I am terrified I will die in a few days in my plane flight for my Australian book tour, I am terrified I will die of late stage Lyme, terrified I will die of the cigarettes I have brought back into my life — I’m terrified. Of a lot! The one saving grace of my mind is that I burn out on all terror — the energy short-circuits and I fall into a weird black zen state and then I feel a sort of very genuine primal fearlessness that lets me do things. Thank goodness for that. Otherwise, on the day-to-day, I am finding life impossible these days, and yet I badly want to live!

So maybe this is a way the good and bad work together. Sometimes good has be there — something has to fill the space. Occasionally, the odds fall with good.

I’m stalling, I think…

Magical Thinking and its cousin Conspiracy Theory are big fears of mine — not unrelated to death! — that are all over The Last Illusion. Asiya becomes the embodiment of all that — in a sense I almost felt her anxiety was bringing on the inevitable 9/11 of the ending, so much that I began to dread writing her with all my heart. But they are also understandable. It makes the world smaller, a culture of superstition. There is something so human about thinking things might not be what they appear. After all: death! Afterlife! What the hell is all that? Dreams even! Babies coming from sex, growing inside and ejecting themselves from human bodies! Shitting! Breathing! (At one point in my Lyme Disease journey I was losing the ability to swallow food and so I would for hours a day read online about swallowing. It’s incredible how it works — how many systems have to operate perfectly for swallowing to happen.)

So much about our lives seem psychedelic to me.

And I tend to be overly empathic and I think that might have to do with trying to infuse meaning into the things I fear. Being on a playground, immigrant kid, not speaking English and having to read people’s faces and gestures for what they thought. I feel like I am always searching, always taking people perhaps too seriously. So when confronted with Magical Thinking and Conspiracy Theory, with all their damages, I have to remind myself this is what happens to good strong minds who feel they can no longer understand the experiment at hand. They create ghosts, they reinterpret reality, they try to bring a sort of rationality and reason to the table. The intention is often a good one and the problem solving here is seductive, but who can live that way? Apparently many but I’m not sure they are living.

RWB: The older I get the more it truly seems that life is a never-ending cycle of the world going to shit, people dying, being killed, horrible, disgraceful treatment of humans by other humans, not to mention the way humans treat other creatures and the environment. When you really get down to it, it’s hard not to think, well maybe Morrissey isn’t so melodramatic after all, or about that comic stereotype of a character in a French film taking a drag of a cigarette and saying “life is shit.” And yet, there are such wonderful, beautiful things woven in, that in spite of it all we keep living, keep striving to live.

Asiya fascinated me, dealing with my own struggles with mental illness I tend to feel discomfited when I can recognize myself in a character, even if it’s just a small piece. In a way she is a ghost herself, she is disappearing into her prophetic hysteria. And while it seems that Zal is attracted to her because she is the first person who gets to know him first as Zal rather than Zal the Bird Boy, Asiya is attracted to him because of his own chaos. She only knows chaos, from her family, to her mental state, to her sense of artistic identity. How did her character evolve? What informed her development?

PK: Asiya: you described her set-up so perfectly that not sure what I can add! I love “In a way she is a ghost herself, she is disappearing into her prophetic hysteria. And it seems that Zal is attracted to her because she is the first person who gets to know him first as Zal rather than Zal the Bird Boy, whereas she is attracted to him because of his own chaos. She only knows chaos, from her family, to her mental state, to her sense of artistic identity.”

Though I’d guess that the chaos is from being parentless. Like Hendricks. Like Zal. Like pretty much everyone in this book.

Asiya, as I said, was the character I least enjoyed writing. For one thing, I have no interest in writing about women with eating disorders. At a certain point when I was very young I suffered from something resembling one, but to be honest, it’s hard to say if I was just very poor and therefore starving or very crazed and starving. Probably both. I know when I was young control was very important to me — much more than it is now (I relish losing control so much these days, more than ever, maybe because of all my years very sick with chronic illness). It was also a way to create shape in my days, to give meaning to my life, to create goals I could achieve. Once I abandoned perfectionism, I no longer had the urge to go there.

It’s my own fault but I don’t love depictions of them in literature usually because so often they fall into the trap of presenting the disease as sexy. Which it is not at all. I know there are many things I can read that surpass this, but I haven’t had the time to look at much of it — but perhaps I will.

But I went there. And as I said, I did not enjoy writing her. But the story made me do it — I had no other choice. I finally have a sense of “inhabiting a story” and “let the characters show you the way” etc, all the old clichés of creative writing workshops that are decent advice!

She seemed black and white to me in so many ways. I was scared of her. I never trusted her and resented her for what she did with Zal.

It’s crazy how real these characters feel to me and yet in so many ways they are symbolic to me. I hadn’t really let symbolism dictate character and plot ever before — and I think it’s actually unadvisable and for good reason! But I wanted the challenge and it so happened that I had a story that wanted that treatment.

As I may have said earlier, the challenge here was to take archetypes and even stereotypes and inflate them into very real life.

RWB: I think you did an amazing job conveying that in the book. And honestly I think there are enough things that I loved about The Last Illusion that I could ask enough questions to fill a book, but I really appreciate you taking the time to talk with me a bit. I’m really looking forward to getting a chance to read your first book, Sons and Other Flammable Objects as well as everything you do going forward!

PK: Thank you for your questions. The dream of any writer — this writer at least, and definitely some I know — is to have someone read their work this carefully and really care to engage them on its ideas. I don’t really make a penny from anything I’ve written but this sort of interaction makes me feel richer than anyone. Thank you. It’s a real gift and I can’t wait to read your work.