Books & Culture

Weird Old Books: Pow-wows with the Pennsylvania Dutch

In order to cure someone who has “fallen away” (i.e. forsaken their Christian faith), John George Hohman suggested catching rain in a pot before sunrise. He wrote, “Boil an egg in this; bore three small holes in this egg with a needle, and carry it to an ant-hill made by big ants… the person will feel relieved as soon as the egg is devoured.”

Hohman was a printer and a bookseller. In 1802, he emigrated from Germany and settled in the Pennsylvania Dutch community of Reading — the same town where John Updike was born a hundred thirty years later. Hohman is best known as the author of Pow-Wows, or Long Lost Friend, published in German in 1820, and translated into English in 1846. Long Lost Friend is a rambling jumble of hexes and household advice. It’s part grimoire, part recipe book and includes everything from spells “to protect cattle against witchcraft,” to recipes for beer and molasses (“Take pumpkins, boil them, press the juice out of them, and boil the juice to a proper consistence. There is nothing else necessary.”) Since its publication almost two hundred years ago, Long Lost Friend has never gone out of print.

Hohman was a hustler, and he had to be. He and his wife and son arrived in the United States with literally less than nothing; to pay for their passage from Hamburg to Philadelphia, they began their new lives as indentured servants. Hohman made money by publishing on the side — occult, religious, and medical books for the ethnic German population. Over time, his business grew. He put out storybooks, New Testament apocrypha, and a collection of hymns.

In 1820, Hohman published Long Lost Friend. In the opening to the book, Hohman wrote that this collection was “partly derived from a work published by a Gypsy, and partly from secret writings, collected with much pain and trouble.” In Grimoires: A History of Magic Books, historian Owen Davies says that large parts of Long Lost Friend are directly cribbed from Romanus-Büchlein, a German spell-book published in 1788. Items within the book can be traced back to dozens of disparate sources.

This helps explain the haphazard construction of Long Lost Friend — how on the same single page, the reader can find advice for catching fish, a remedy for ulcers, directions for healing inflammation, and a spell “to prevent wicked or malicious persons from doing you an injury.”

Hohman said that he opposed the publication of this collection. His wife opposed it, too. He wrote, “But my compassion for my suffering fellow-men was too strong, for I had seen many a one lose his entire sight by a wheal, and his life or limb by mortification… is it not to my everlasting praise that I have had such books printed? Do I not deserve the rewards of God for it?”

Hohman was bold in pitching his work. Among other sales strategies, Long Lost Friend begins with a list of take-Hohman’s-word-for-it testimonials (“ANDLIN GOTTWALD, formerly residing in Reading, had a severe pain in his one arm. In about 24 hours I cured his arm,” etc.).

But the most significant and resounding sales ploy used by Hohman appeared on the final page of the book, where in a short passage floating above three crosses, it reads: “Whoever carries this book with him is safe from all his enemies, visible or invisible; and whoever has this book with him cannot die without the holy corpse of Jesus Christ, nor drown in any water, nor burn up in any fire, nor can any unjust sentence be passed upon him. So help me.” As Davies points out, “People purchased the Long Lost Friend not only for its contents, but also for its inherent protective power.”

Davies writes about how this strategy demonstrably worked. In a 1928 interview, Charles D. Lewis explained that he had carried the book with him for sixteen years — working as a fireman on steamships — and had evaded physical injury. Lewis said he lost his book when the British seized his liner, and soon after, suffered a life-threatening accident. Frantic, Lewis secured a new copy of Long Lost Friend as soon as he possibly could.

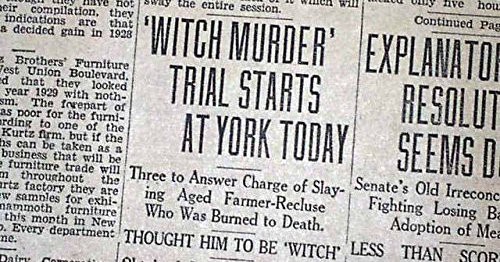

The best example of the haunting impact of Hohman’s final page is demonstrated in the 1928 murder at Hex Hollow. Central Pennsylvania ruffian John Blymire was a man with terrible health and fortune. Blymire suffered from malnutrition, and his first two children died within days of their birth. When he was thirty years old, he lost his job, his wife left him, and he was committed to a state mental hospital; forty-eight days later, he escaped by walking out the door.

On the lam and under the consultation of a witch named Nellie Noll (a.k.a. “The River Witch of Marietta”), Blymire came to believe that local pow-wow doctor Nelson Rehmeyer had hexed him. Blymire convinced a 14-year-old and an 18-year-old that Rehmeyer had hexed them, too; the three of them broke into Rehmeyer’s house at night with the explicit purpose of finding and destroying his copy of Long Lost Friend.

Instead they found Rehmeyer in his PJs. They beat and tied the pow-wow doctor up, and demanded he relinquish his copy of Hohman’s book. Rehmeyer played dumb; the 14-year-old picked up a block of wood, knocked Rehmeyer over the head and killed him. Blymire took a lock of Rehmeyer’s hair to bury under ground (The River Witch had told him to), and then the three of them unsuccessfully tried to burn down Rehmeyer’s house. A few days later they were arrested for murder. Blymire proudly confessed, bragging he had killed the witch who had hexed him.

For its sinister history, Pow-Wows, or Long Lost Friend is actually a pretty benign book. Its hexes are mostly designed to prevent or eliminate danger, rather than to create it. Hohman’s spell to stop bleeding demonstrates the oftentimes toothless nature of his trade: “Count backwards from fifty inclusive till you come down to three. As soon as you arrive at three, you will be done bleeding.” That’s time passing; that’s often how people stop bleeding. To make a buck, Hohman takes credit for it.

While Hohman was able to buy his way out of servitude and make a living for his family, he never achieved any great wealth. He died in 1856, before his book had achieved much beyond local distribution. But Davies writes that by the early twentieth century, numerous further editions of the Long Lost Friend “had ensured that it was firmly cemented in the medical tradition of ethnic Germans.”

Whether it was for pious or self-serving reasons, Hohman invested his soul into what he sold. He wrote that he knew the majority of sensible people believed in him. But he was a reasonable man, and he recognized that there were doubters. “This latter class I cannot help but pity,” Hohman wrote, “ and I earnestly pray everyone who might find it in his power, to bring them from their ways of error.”

You decide which camp you fall into. The full text of Long Lost Friend can be found online here, but Hohman would probably recommend getting a physical copy — for your own well-being.