Novel Gazing

What a Cross-Dressing Lady Knight Taught Me About Gender and Sexuality

Tamora Pierce’s ‘Song of the Lioness’ series helped countless girls to be strong—but for a gay boy, the lessons were a little different

Novel Gazing is Electric Literature’s personal essay series about the way reading shapes our lives. This time, we asked: What book was your feminist awakening?

On the morning of my first day of high school, everyone in my homeroom sat in silence — stiff-backed and rigid and afraid, sweating through the dress shirts our mothers had bought for us. No one knew what the social hierarchy was here, at this all-boys Catholic school where black-robed friars walked the halls and the upperclassmen towered over us, their voices deep enough to be our fathers’. It seemed better, that first morning, not to risk breaking any unspoken rules. It seemed better not to speak at all.

But this unnatural reserve didn’t last long: by mid-September, my homeroom buzzed with voices. The boys around me complained about our biology homework, and speculated together over whether the Bills had a shot at the Super Bowl this year. Most of all, though, they liked to talk about the girls at our sister school. Sluts, the boys called them, in an easy, matter-of-fact tone that made me flinch. Whores. Their disgust became even more pronounced when they talked about gay men. Fags, they said, the word making little tendrils of alarm uncurl along my spine. Homos. Worst of all were the times when my new classmates pretended to be gay. They lisped their words and waved around boneless wrists until it was clear that to be gay was also, in some mysterious but definite way, to be a grotesque parody of a woman.

While all of this happened, I stayed quiet. Watchful. Whenever I was at Saint Francis, my chest always went tight with fear, and I clenched my teeth until my jaws ached, reminding myself to always be careful. Every now and then, though, I slipped up.

Once, in the early weeks of school, I watched a group of freshmen play dodge ball with some upperclassmen. I couldn’t stop looking at one senior boy, the class president: earlier, he’d spoken to all the freshmen in the dim quiet of the school chapel, lecturing us about responsibility and respecting our teachers. Shirtless now in the cavernous gym, he ducked and wove and whipped until sweat gleamed against the lean muscles of his chest. I was still watching him when another boy stepped close and murmured something in his ear.

I had a fraction of a second — just long enough to feel a flicker of doubt, long enough to hear more acutely the squeak of sneakers and the boom and crack of balls — before the senior turned his head to look right at me, dark eyes pinning me in place. Caught.

And though I looked away immediately, I could feel the heat rising under my skin, shame flaring inside me like a lit match.

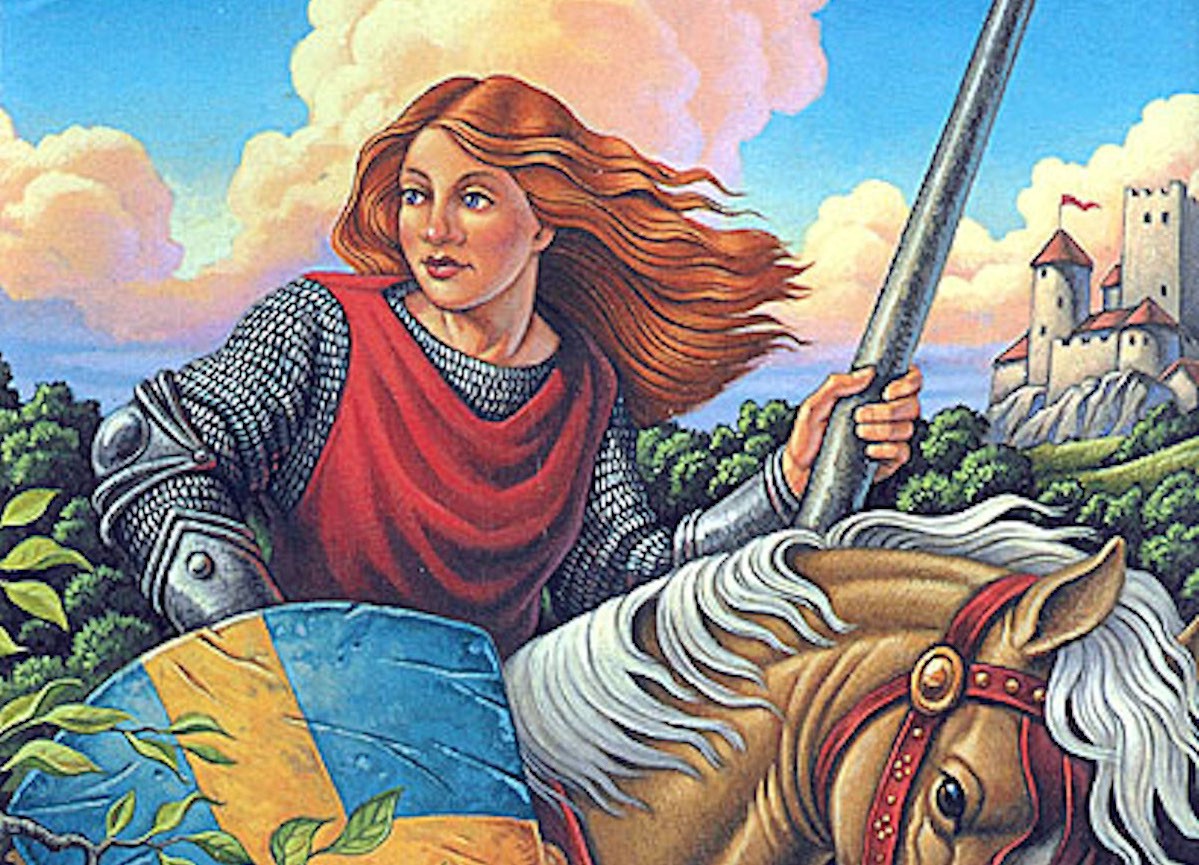

After days like these, there was only one way I knew to feel safe again, one way to make my muscles loosen and my jaw unclench. On the bus ride home, I would curl up with Tamora Pierce’s Song of the Lioness quartet, a series of young adult fantasy novels that detail the adventures of Alanna, a teenage girl who disguises herself as a boy in order to train for knighthood in the medieval kingdom of Tortall. I first began devouring the series in middle school, reading and re-reading the pastel-colored paperbacks until they were dog-eared, their spines broken from being opened again and again. But the Alanna books became even more important to me as high school began. Oddly enough, they felt relevant in a new and pressing way. Because even though she had violet eyes and a horse named Moonlight, Alanna’s daily life training at the palace ran strangely parallel to my own at Saint Francis.

In the first books of the series, Alanna has to keep her true identity a secret from her classmates. She refuses to go swimming, even on the hottest summer days, and binds her breasts once she starts developing. Despite these obstacles, she does well at the palace, making friends and facing down bullies. When one of them breaks her right arm, she starts to train with her left, practicing relentlessly until she’s ambidextrous. And yet, Alanna is still nagged by self-doubt, a creeping sensation of inferiority. Even after she finally defeats the bully who broke her arm, she can’t quite let herself feel proud of what she’s accomplished. “She was still,” the narrator tells us, from a perspective deep inside Alanna’s mind, “a girl masquerading as a boy, and sometimes she doubted she would ever believe herself to be as good as the stupidest, clumsiest male.”

For reasons I was only beginning to make out, Alanna and I were kin.

My freshman year at Saint Francis began in the fall of 1999, a time when there were very few YA novels about gay teens. But even if more had existed, I would have been too afraid to read them: afraid both to be seen with these books, and afraid to identify with their main characters. The Song of the Lioness series let me think about the experience of being closeted in a way that was safely distanced from my real life. In Alanna, I found a heroine who thrives despite her inability to come out, and despite the psychological costs of remaining in the closet.

In Alanna, I found a heroine who thrives despite her inability to come out, and despite the psychological costs of remaining in the closet.

The novels also held another truth, one I wouldn’t be able to fully register for another few years: how important it is to fight back against all those voices — both outward and inward — that claim that being either female or effeminate is disgusting and shameful.

If Pierce’s books armed me with a nascent feminism, they also helped me make real friends. Right before my freshman year began, my mother brought home a new, internet-enabled computer. I used it to find fan sites devoted to the world of Tortall. Hosted on free websites like Angelfire, GeoCities, and Tripod, these sites had names like “Lady Jayla’s World of Fantasy,” “Seraphsong’s Page,” and “The Dream Plains” — and nearly all of them, it turned out, had been made by girls around my own age. Soon I was trading long emails with half a dozen other fans. Our letters started out as detailed discussions of Pierce’s books, but before long the focus shifted to our daily lives: our friends, our schools, our families. These were the bookish, clever, sarcastic peers I couldn’t find at Saint Francis, but desperately needed in my life. Even now, almost twenty years later, I can tell you their names: Shanti, Alison, Kel, Eiram.

Before long I started role-playing with some of these friends online, in a chat room devoted to Pierce’s world. After the daily fear and silence of high school, the relief was incredible. In the chat room (which, for game purposes, was a tavern in Tortall), there was no need for macho posturing, no need to worry about my high, feminine voice or my short, weak frame. We were in a place where bodies vanished, leaving only our words — and those, too, would be gone the next time we logged in. Safe in this knowledge, I relaxed. I let myself be warm and funny and playful: all of the things I couldn’t allow myself to be at Saint Francis.

But I let myself be more than those things, too. My character, Darius, was a mage, and he always entered the chat room — the tavern — in the same way: he appeared magically, “in a blaze of silver fire.”

At school I wanted to be forgotten, to erase myself like an Etch-a-Sketch when you shook it hard enough. But in front of the new computer, chatting with all my new friends, I wanted so much more. I wanted to burn with a light that you wouldn’t soon forget.

Today, more than three decades after the publication of the first book in the Song of the Lioness series, many millennial-age women have written about how Pierce’s heroines provided them with powerful feminist role models. In her blurb for Pierce’s latest book, the author Sarah J. Maas writes that Pierce’s novels “shaped me not only as a young writer but also as a young woman. Her complex, unforgettable heroines and vibrant, intricate worlds blazed a trail for young adult fantasy — and I get to write what I love today because of the path she forged throughout her career.” Author Bruce Coville, meanwhile, observes that, “Having been with Tammy at signings and listened to the young women who speak from their hearts about how they were empowered by her books, I know it is impossible to overstate her impact.”

But the Alanna series was valuable to me for slightly different reasons. Long before I took classes in feminism and queer theory, it helped me to understand that misogyny is a weapon wielded against women and gay men alike. And it promised me, too, that this weapon could be overcome. The first book in the Song of the Lioness series culminates in a chapter where Alanna and her close friend, Prince Jonathan, enter the mysterious Black City and fight a group of evil creatures known as the Ysandir. Midway through the battle, the Ysandir realize that Alanna is actually a girl and use their magic to burn away her male clothes in an attempt to humiliate her. Although Jonathan is shocked to learn Alanna’s true identity, he keeps fighting alongside her, and together they defeat the Ysandir.

Long before I took classes in feminism and queer theory, ‘Alanna’ helped me to understand that misogyny is a weapon wielded against women and gay men alike.

In the final pages of the book, Jonathan — who has been trying to decide which of the knights-in-training he should select as his squire — asks Alanna whom he should choose. “A week ago,” the narrator tells us, “she would have told him to pick Geoffrey or Douglass. But she had not been to the Black City then. She had not proved to the Ysandir that a girl could be one of the worst enemies they could ever face.” Alanna keeps thinking about her time training at the palace, remembering all her hard work, all her accomplishments. “All at once,” the narrator says, “she felt different inside her own skin.”

Alanna tells Jonathan that he should pick her, and he says that she was already his first choice.

She felt different inside her own skin. The first time I read that sentence, more than twenty years ago, it was a promise. A promise that I would not always be so afraid, a promise that I could fight — and win — against all the voices that crackled inside me, telling me that I would never be as good as the stupidest, clumsiest male.

She felt different inside her own skin. It was a promise, but also a gift — one as beautiful and unexpected as silver fire.