interviews

What Do Bruce Springsteen and Chance the Rapper Have in Common?

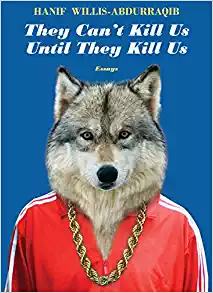

Hanif Abdurraqib‘s new collection asks the big (and small) questions about modern music

They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, the first essay collection from Hanif Abdurraqib, is a towering work full of insightful observations about everything from the legacy of Nina Simone to the music of Bruce Springsteen. Throughout the book, Abdurraqib juxtaposes the societal with the intimately personal, and the end result is a powerful work about art, society, and the perspective through which its author regards both.

In the waning days of summer, I talked with Abdurraqib about the way his book came together, how it relates to his work as a poet, and how the powerful and cumulative structure of They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us emerged. An edited version of our conversation follows.

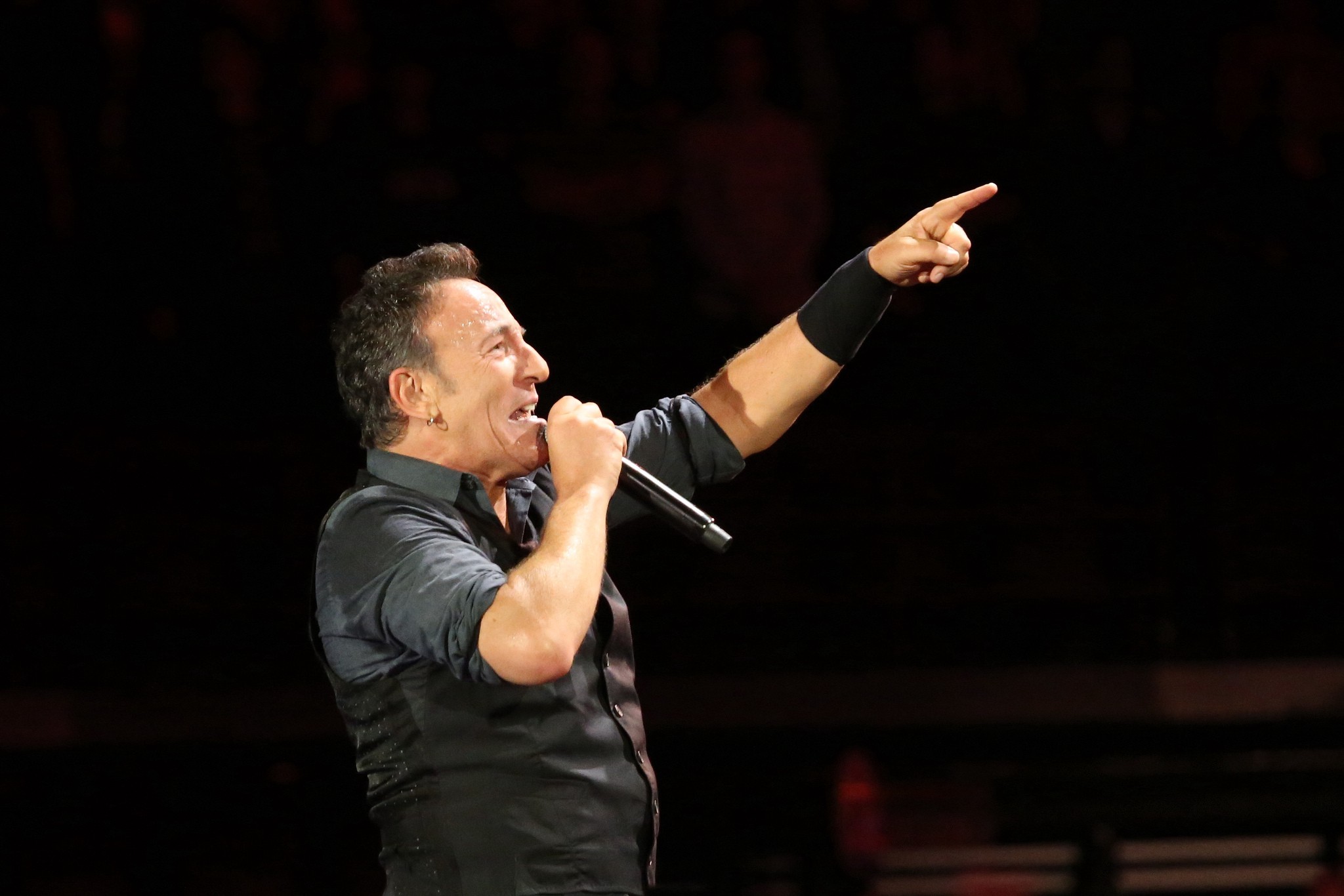

Tobias Carroll: Your book opens with back-to-back essays about Chance the Rapper and Bruce Springsteen, both of whom are very much associated with particular places. Did you have that structural decision in mind from the outset, or did it come later?

Hanif Abdurraqib: It came later. But I think it makes sense, right? They’re both artists who are speaking to a unique American experience, more than just a distinctly geographical one. Their vision of what freedom in America looks like is governed by two vastly different frames. That’s in part because of their demographics: Chance is younger; he is black; he is of a different era and a different place. I was really interested in examining Springsteen’s relationship with labor as freedom, and who in America gets to claim that gleefully and who gets to feel like that’s a burden.

I was interested in Chance particularly because his idea of freedom is tied to this idea of inexhaustible joy in the face of whatever is trying to take it away. I don’t know if I believe in that, but I was interested in his belief in that. With both of these artists, it’s the same thing. I don’t know if I believe them. I don’t know if I believe in what their ethos is telling me, but I’m interested in why they believe it.

Will Spotify Kill the Local Music Scene?

TC: Did you find that the process of writing about these musicians caused your views on them to change over time?

HA: It’s refined it more. I’ve been a Bruce Springsteen fan for pretty much my whole life. I’ve grown up with, and grown into, the great Springsteen narrative, so my interest in Bruce Springsteen is always shifting. Especially because in so much of his work, particularly in his earliest eras, he’s hinting at some sort of escape. But it’s not an escape from anything, really, because all of his characters are still riddled with this Jersey lower-middle-class minutiae of waiting for a weekend. Listening to Bruce complicates my opinions of him.

The piece in the book is more about complicating what it’s like to be at a Bruce Springsteen show, and to take in everyone at a Bruce Springsteen show and the Bruce Springsteen of now. That’s different than the Bruce Springsteen of the Hammersmith Odeon in 1975. The audience is dreaming more, but he’s decidedly more cynical; he’s performing to an audience of dreamers, but I don’t know if he believes himself as much as he used to.

TC: As someone who grew up near the Jersey shore, that mythic Springsteen figure has definitely loomed large in pop culture for me.

HA: It seems like the songs he believes most now are the ones where there’s no happy ending. Like “Atlantic City,” for example. “Atlantic City” is this harrowing tale where you’re on the edge of your seat, waiting and waiting and waiting for this terrible life to resolve itself into something better. The song opens with the image of a house being blown up, and it doesn’t resolve itself. That’s why I think “Atlantic City” is great — it opens with this image of a house being torn apart and a fight on the boardwalk in a city that doesn’t know how to handle itself. The central character in that story, the speaker of that song, can’t make a better life for himself. He never makes a better life for himself. The last verse of “Atlantic City” is so harrowing, that last line of “Last night I met a guy, and I’m going to do a favor for him.” It’s a person who’s at their wit’s end, and we are to assume that they’re getting by on ill means. Everyone in the song is facing consequences for things they’ve done wrong, and in the end, the character himself says, “Well, I am now one of these people who is going to do something wrong, despite the consequences and how I know it’ll play out.” And that is the Springsteen dream turned on its ear.

TC: Did most of the pieces about music in the book originate as freelance assignments, or were they written with the book in mind?

HA: About half and half. Some of that stuff was published in places like MTV News, where I worked for about 18 months. There’s a piece in there from the New York Times, one from Pitchfork…The thing for me is that I love music, and I think about music all the time. A cool thing about having an essay book is that you’re not beholden to any strict timeline. There were things I wanted to explore that I certainly couldn’t publish anywhere because they weren’t “topical.” I could really grind away at them in that book in a way that felt good. A lot of the things that were rattling around in my brain for several months could finally get outside of my body and have a place to live, outside of me rambling to my friends in bars about pop-punk.

TC: There are a few places in the book where you quote Lester Bangs, including a piece that’s written as a homage to “Sham 69 Is Innocent!” Were there any other music writers who you wanted to invoke or engage in dialogue with through this book?

HA: Bangs is important to me. I’m glad that you mentioned the “Sham 69 Is Innocent!” thing, because that’s my favorite piece of music criticism ever written. It’s this absurd collection of statements, and I feel about Twenty One Pilots the way Bangs felt about Sham 69. I feel that there was a clear lineage for me to bring him up in that piece. He was endeared to Sham 69, but also, “Oh…..those guys.” I’m from Columbus; Twenty One Pilots are from Columbus. I’m endeared to them, but I also have moments where I go, “Oh…those guys.”

I think that Bangs and Greil Marcus are in a similar lineage. Greil Marcus is so good at drilling through the music to get to the story underneath it. I really wanted to do that. And I wanted to honor both Bangs and Greil Marcus, especially because Bangs was so good at making the reader feel like they were in on the joke. I don’t want to write about music in a way that makes people feel like they have to be a music fan to understand why I like it. I don’t want to write about music in a way that makes people feel like they have to be up on the latest things to appreciate what I’m trying to get at. I’m not trying to get the reader to like the music I like — I’m trying to convince them that it meant something to me. The music is kind of perfunctory.

Jessica Hopper is a massive influence on me. There was actually a piece that got pulled from the book that was written after a piece of hers. I really wanted to honor the impact that she’s had on my writing. She was my editor for several months at MTV; she edited me when she was at Pitchfork. There’s a working relationship there, but I’ve also just been a fan of her criticism and her insistence on the fact that music is not a small or stupid thing. Pop culture is not small or stupid. It should be treated with respect; critics should look at it with respect and write about it with a level of respect. I was trying to honor that as well.

Pop culture is not small or stupid. It should be treated with respect.

TC: Is that why you began the book with music and gradually expanded it to include questions of family, faith, and race?

HA: Yeah — it’s a reverse blooming. I opened with music because I want to open my palms so that everyone can feel welcome. I don’t want to crush people, obviously, but slowly making the stakes smaller and smaller and making the space more intimate — that’s a gift that a writer can give a reader. I opened with music to say, “Here is a conversation I want you to be in. Here’s a peg that you might be comfortable with, and I want you to be in on this conversation that I’m going to get to later.” And by the time you actually get to the conversation, people are either uncomfortable or a little more comfortable, but they’re there. I wanted people to feel like I was talking to a part of them that they were comfortable with. I wanted people to be able to step comfortably into a conversation that was going to get gradually more difficult.

TC: In the book, you talk about having spent time in the Columbus punk scene. Do you feel that that had any influence on shaping you as a writer?

HA: I think I am less romantic now about being in a punk scene than I was then. I was often the only black person on the punk scene, or definitely othered by a punk scene. When you are a token in a setting that is branded as a familial setting, even your othering can feel like it’s a part of this familial ritual. Even the fact that you are being distinctly othered by people can feel like it’s done out of this sense of brotherhood. Which, at the time, I needed. At the time, I was in my late teens, and that was a thing I needed. That was where I felt most like I fit in.

It did also teach me a lot about the lengths that we will go to — and when I say “we,” I mean “me,” and I particularly think, at least in my punk scene, of young straight men — the lengths that will go to to escape emotions, and the reckoning that comes when those emotions come back to live, to live a full life. If anything, growing up in in a punk scene pushed me to a level of vulnerability in my writing that I don’t think I ever would have gotten to. I want to be vulnerable because I did not see a blueprint for vulnerability in the scenes I was in, and I saw the damage that did to people. And I saw the damage it did to me, personally.

At least in the scene that I was in, there was a lot of performed vulnerability in the musicians. We demand a performance of vulnerability that we think is going to transfer to us, but instead it all feels like a performance. I think it’s easy to perform vulnerability when the stakes are low. It’s significantly harder to come correct and come through with real, actual, sustainable vulnerability that allows you to, for lack of a better term, be in your feelings when you need to be in your feelings, and handle that in a way where it doesn’t harm or put other people at risk.

I want to be vulnerable because I did not see a blueprint for vulnerability in the scenes I was in, and I saw the damage that did to people.

TC: You write about the phenomenon of bands playing songs that express sentiments that they felt in their 20s a decade later, and how that doesn’t always age well. Do you find that that’s the case with a lot of the artists that you liked at a certain point in your life, or does it vary from artist to artist?

HA: I think it varies from artist to artist. I do think that there’s a specific brand of early-to-mid-2000s emo or pop-punk album wherein a dude or several dudes are angry at a woman or several women. I’m thinking of the first Fall Out Boy album. The longest piece in the book is a piece about Fall Out Boy, so I have a lot of love for them, but that first album is horrifically violent. It’s all about how much Pete Wentz wants his ex-girlfriend to die. That’s played out in a very literal way. I’m thinking of Mayday Parade’s A Lesson in Romantics, which is kind of bad in the same way, and Cute is What We Aim For’s The Same Old Blood Rush With a New Touch. The first Brand New album is also in that same vein. There’s a brand of album that really leans into this idea of punishing women who rejected the men in the band.

That’s not specific to this genre, and it’s not specific to music. It’s specific to men and the world we live in. Just a couple of days ago, there was a story of a man in Dallas who rolled up to his ex-wife’s house and shot everyone inside.

I don’t want to pretend that this is a specific thing to a genre. But if you’re talking about things that don’t age well, that hasn’t aged well for me. In my criticisms of those albums and those songs, it’s been vital for me to be honest with myself and remember that there was a time when I loved those songs. There was a time when I sang along with those songs. In order for me to properly critique them and properly write on them, I needed to reckon with myself on why I liked them, and not just chalk it up to, “Well, I was young.” That’s an easy window out, and I’m interested in creating harder windows out for myself so that I might, hopefully, be a better critic at the end of it.

Support Electric Lit: Become a Member!

TC: You mentioned your book of poetry. Did you start writing nonfiction before you wrote poetry, or did the two go hand in hand for you? Have the two started to influence one another?

HA: They’ve definitely started to influence one another. First, I was a freelance music journalist writing for no money for a long time, or writing for very little money. I started writing poems in 2012, and then I decided to take poems very, very seriously. I stopped writing all other things, and really studied poetry. I got a lot of poetry books and locked myself away and studied poetry the best I could without going to get an MFA–and then came out writing poems that were better than the ones I started writing.

I returned to music writing around 2015. I wrote a thing about “Trap Queen” and it picked up a lot of buzz. That’s when Jessica [Hopper] reached out to me about writing for Pitchfork, and eventually for MTV. It was kind of like a domino effect.

I hope this shows up in the book: I think the poetry and the longform work both inform each other. There’s a thing in the book that’s literally a poem; I just removed the line breaks. There’s that thing about Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston. It’s a poem–I just made the sections in the paragraphs instead of having line breaks, like it was before. But that’s not an essay. That’s not making a linear, clear argument for anything. It’s making a metaphorical argument for a thing. I think “Defiance, Ohio is the Name of a Band” is more of a poem than an essay, but it’s kind of like neither.

I know that, because of this book, a lot of people are going to want to talk to me about genre. I get that. But I don’t know how to explain this idea that I sit down to write and I am, at my heart, sitting down to write a poem every single time. I envision everything that comes out of that to be driven by my desire to write a poem. If I write an essay, in some ways it’s an essay because people say it’s an essay. But it was driven by desire to write a poem. That doesn’t mean I’m a poet and only a poet; it just means that my idea of genre is not restrictive. My idea of genre is that I have many ways to get to many end results. But I’m driven to the page by my love for poetry, and if I’m lucky, then other things come out from time to time.