interviews

What Does It Take for Ultra-Orthodox Women to Leave Their Repressive Lives?

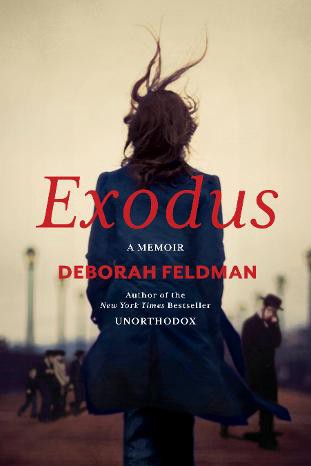

Deborah Feldman, who left her Hasidic Jewish community for Germany, discusses her newest memoir

I met Deborah Feldman in Brussels at the end of January, when she was invited by the Goethe Institute to talk about Überbitten, the expanded German edition of her second memoir, published in English as Exodus.The book renders with bare honesty Feldman’s experience parting from orthodox Judaism, the only world she knew, and reinventing herself in a different country.

Feldman achieved notoriety after her first book, Unorthodox, was published in the U.S. in 2012. In it, she describes the repressive nature of her life within the Satmar Hasidim community in Williamsburg, her arranged marriage at 17, and her subsequent decision to take her son and leave the community.

For Feldman, history is a kaleidoscope where the past can morph if observed from different angles. In the second half of Überbitten, she explores her life in Germany, her relationship with Germans, and the way the Holocaust is understood and integrated in the collective consciousness there. As a descendant of Holocaust survivors, she asks fundamental and tough philosophical questions. Had she been a Nazi, would she, in all certainty, have refused to carry out acts of violence and annihilation? As in most aspects of life, the answer is not cut and dry.

I spoke to Deborah about her books in Brussels, and later continued our conversation through email. Our conversations focus on the Hasidic community’s relationship with motherhood, infertility, and women’s bodies.

Mauricio Ruiz: In Unorthodox, you explore the themes of motherhood and fertility. These days, some women have the choice to decide whether they want to have children or not, and when; others still do not have that choice. How do women who do not want to have children cope with this reality in Hasidic communities?

Deborah Feldman: I do not think this is a reality anyone I knew ever “coped” with. The greatest social misfortune in this community is infertility. It is grounds for divorce. Women who cannot produce children are relegated to the lowest possible position in society, they are seen as completely useless, purposeless, valueless. In Unorthodox I describe how I was treated in the first year of my marriage in which I failed to become pregnant: I was threatened with divorce, homelessness, complete abandonment, I was subject to abusive criticism of my basic worth as a human being, I was made to understand that my ability to have a child was my only value and that if I failed to fulfill this expectation I would be treated like waste. So I think in this atmosphere it is not actually possible to entertain ideas about rejecting childbirth, because reproduction itself becomes a form of survival, and those survival instincts are very strong.

MR: Could you talk a little about your mother? What were your thoughts and reflections about her while you were growing up? Did you have mixed feelings (because she had pursued the life that she really wanted; sad because you couldn’t spend time with her)?

DF: I think my feelings could be described as a mixture of fear and curiosity. The latter because it was this great unknown, this outside world to which she had fled, and the concept of a life and an identity out there, and the former tied to the understanding that we are doomed to repeat familial patterns, that her fate could determine my own.

MR: When talking about Exodus, you mentioned that when a Hasidic woman in Israel decides to leave the community, she doesn’t enjoy the same rights as another non-orthodox woman under the Israeli Constitution. Could you elaborate a little bit more on that? Wouldn’t this be a violation of human rights?

DF: I think to understand this you have to research how the Israeli government works. There is this awkward coalition between the secular and orthodox parties in which exceedingly questionable political deals are made that have very little to do with democracy, but are a result of what happens when a democracy includes a sizable anti-democratic element. You have an agreed-upon segregation of Israeli society, in which members of orthodox communities are subject to biblical law and religious dictates, while secular members have access to a whole different set of laws and rights. A problem occurs when a member of the orthodox world wants to cross over. Orthodox parties will not accept that secular Israeli society will step in to support this “runaway” with its granting of new civil rights or defend it against the laws and restrictions of the society he or she has left. It demands that all of its members, both current and former, be seen as in their “jurisdiction.” So in the name of a fragile political detente, runaways are left in a kind of no man’s land between the two worlds; they are required to make their way across to the other side completely at their own risk.

Runaways are left in a kind of no man’s land between the two worlds; they are required to make their way across to the other side completely at their own risk.

MR: Referring to the case of a famous Israeli writer’s sister happily living in the settlements, you explained that human beings tell themselves everything is okay, that they are happy. It’s a self-preserving mechanism. What do you think it would take for women living in the settlements to be able to see what you’ve come to realize?

DF: I really do not know. I think my realization came about because I had this curiosity about another world, another perspective, and I sought contact with it. So I was able to develop alternate modes of thinking. But what do you do with people who are to afraid to nurture this curiosity

MR: While explaining the religious philosophy of the community you grew up in, you mentioned the three oaths upon which orthodox Judaism was founded after the destruction of the Second Temple:

a) Do not try to take the land.

b) Submit completely to the authorities in exile.

c) Establish and make clear the differences between yourselves and the people in the countries where you live.

How was that reshaped after the Holocaust? What narrative was created by the scholars and rabbis?

DF: These are the Three Oaths, and they are known to all Jews all over the world, and may be interpreted differently depending on the community, but they are part of a common diaspora heritage. I think the way my community reshaped the “myth” of oath-based punishment versus redemption after the Holocaust was to claim that we were living in a time when Jews wanted to cast off this pact they had made with God, they wanted to take back the land (zionism) assume political authority or at least equality in their various countries and cast off their differences by clothing themselves, naming themselves, and speaking in a manner that was customary in whatever society they might find themselves. The Rabbis claimed that this was not only rendering the promised eternal redemption impossible but also bringing on a kind of apocalyptic temper tantrum from a God who had proven, with the Holocaust, to no longer be able to contain his rage and frustration with this forgetful children.

Meaghan O’Connell Thinks Motherhood Is What Keeps Women Oppressed

MR: In your books you explore women’s relationship to authority, especially religious authority. Why is it, in your opinion, forbidden for women to read the Talmud? Will there be a day when it isn’t?

DF: The tradition of reading and discussing the canon of Jewish texts has always been masculine in the orthodox community. On the other hand women are reading these texts in reform Jewish communities. The ideology of Orthodoxy will not allow for women to do so within their own world. This is just how religion works. I think it is not very realistic or productive to discuss ways in which radical patriarchies can make adjustments or allowances for women, since to do so would require a crumbling of their very foundations. Perhaps we need to learn to accept that the two poles are irreconcilable, and it is not our obligation to find ways in which to render such communities more acceptable to us. I find efforts to engage in “cultural understanding” very naive and counterproductive. I would appreciate it if Jewish secular liberals had more confidence in their own value system and were able to criticize instead of chalking it all up to cultural differences.

MR: You read a beautiful passage from Unorthodox where you, for the first time, decided to break an imposed rule. I really liked that, the idea of questioning the rules that govern our lives. How do you think people living in Israel, and the world in general, could become more conscious of the rules that govern their lives?

DF: Isn’t our whole capitalist society structured in a way as to prevent this?

MR: In Unorthodox you recount the anecdote where one day you forgot to put on one of your garments (the rule being: knitted on top of woven fabrics to avoid revealing too much of the female figure) and later being sent back home to change. There seems to be a constant control of women’s bodies, and women are often made to feel, unjustly, guilty for bad things that happen in the world. Do mothers, grandmothers enforce those rules (given that they know what it means to feel that themselves)?

DF: Yes, women do enforce this, because they are taught that they will be rewarded for this with approval, even power. This happens in the Jewish secular world as well.