Books & Culture

What Flannery O’Connor Taught Me About Chronic Illness

I wanted evidence that being sick had damaged her spirit, too

I n the fall of 2012, when I was suffering from the rheumatic symptoms of what I called my “phantom illness,” I read Wise Blood, Flannery O’Connor’s first of two novels. I read the book over the course of several warm baths I took to ease the ache in my joints. None of the doctors I visited had offered a conclusive diagnosis for my complaints, which, in addition to arthritic pain, included traveling rashes, fatigue, mental fogginess, amenorrhea, occasional numbness and discoloration in my fingers and toes, and the loss of about half of the hair from my head.

I had begun to feel ill while living in Savannah, Georgia, and soon after, at age twenty-nine, I relocated to my mother’s home, in North Carolina, for what I believed would be a temporary spell of medical tourism: visits to family doctors who might offer referrals to specialists at Duke and UNC-Chapel Hill. I left my clothes and furniture and books in Savannah and returned often enough to convince myself that I had not, in actuality, moved in with my mother.

When I took Wise Blood into the bath that fall, I had maintained a moderate interest in O’Connor and her work. I found the paperback volume at my mother’s house, on a shelf filled with novels I supposedly studied in college literature courses. I had certainly, if intermittently, read from The Complete Short Stories, a chronological printing of O’Connor’s short fiction with an introduction by her editor Robert Giroux; and I had once visited the author’s childhood home in Savannah. I had seen the bathtub the author filled with pillows before climbing in to read stories as a young girl and the view of the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist, where the family attended church, framed by every street-facing window. I had seen the white wicker pram with its gold-leaf monogram: MFO’C for Mary Flannery O’Connor. I had stood in the sunroom next to the faded chaise where O’Connor’s father, Edward, lay for afternoon naps that would eventually be understood by his family as the earliest signs of the lupus that killed him at age forty-two — the same disease that killed his daughter at age thirty-nine.

I don’t make no plans.

— Flannery O’Connor

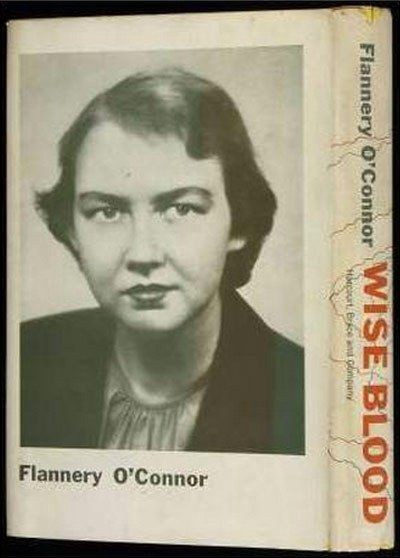

In winter 1952, roughly two months shy of her twenty-seventh birthday, Flannery O’Connor posed for her first author photograph. Wise Blood was scheduled for release that May, and her publisher, Harcourt, Brace, had requested a picture for the back of the book jacket. “They were all bad,” O’Connor wrote to the poet and translator Robert Fitzgerald and his wife, Sally. “The one I sent looked as if I had just bitten my grandmother and that this was one of my few pleasures, but the rest were worse.”

O’Connor was living in her native Georgia by then. After several years away, during which she earned her MFA at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and spent time at Yaddo, she had come back to her family dairy farm on the rural fringe of Milledgeville, a pretty town of white-columned buildings. She had not, however, returned willingly. Systemic lupus erythematosus had begun to plague her body at least a year earlier and driven her back to the care of her mother, Regina, and the various aunts, uncles, and cousins who lived nearby.

She had been renting a room in the Connecticut home of the Fitzgeralds when the illness struck, working on her novel and enjoying the intellectual camaraderie and mentorship of the likes of Alfred Kazin, Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Hardwick. Years later, Sally Fitzgerald recalled depositing the ailing young writer on a train that would return her to her home state for what both women believed would be a temporary visit: “She looked much as usual, except that I remember a kind of stiffness in her gait . . . By the time she arrived, she looked, her uncle said later, ‘like a shriveled old woman.’”

Regina had received the diagnosis but hid it from her daughter for nearly a year and a half, preferring instead to tell her she was suffering from rheumatoid arthritis.

When she sat for her Wise Blood photograph, little more than a year after that train ride and a subsequent hospitalization, O’Connor still assumed her stay in Georgia would be impermanent. This is the story Sally Fitzgerald told when she edited The Habit of Being, a collection of O’Connor’s letters published in 1979. O’Connor did not yet know she was afflicted with lupus. Regina had received the diagnosis but hid it from her daughter for nearly a year and a half, preferring instead to tell her she was suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. Only in the summer of 1952 did she come to understand her true condition.

In an interview conducted years after O’Connor’s death, Sally Fitzgerald disclosed that she had been the bearer of this medical information, which she had received in confidence from Regina. Shortly after this conversation with Fitzgerald, O’Connor acknowledged her malady in precise terms, writing, “I now know that it is lupus and am very glad to so know.”

Her collected letters reveal her pragmatic response to the news. She sent for the personal belongings she had let linger in Connecticut: a Bible, two suitcases, and a copy of Art and Scholasticism by Jacques Maritain. She ordered “a pair of peafowl and four peachicks from Florida,” the first members in a flock that would eventually number in the forties and devour the entirety of her mother’s garden except, for some reason, the irises. And she began attempting to develop as a writer amid the strictures of sickness and her middle-Georgia geography. About her authorial image, she revised her assessment in no less brutal terms: “The book itself is very pretty,” she wrote to the Fitzgeralds after receiving her first copies of Wise Blood, “but the jacket is lousy with me blown up on the back of it, looking like a refugee from deep thought.”

“The book itself is very pretty,” she wrote to the Fitzgeralds after receiving her first copies of Wise Blood, “but the jacket is lousy with me blown up on the back of it, looking like a refugee from deep thought.”

The photograph and the timing of its taking, several months before O’Connor knew the gravity of her condition, are, to me, significant. The high fever that had hospitalized the writer a year earlier had shocked her body and caused her to lose much of her hair. The steroids she took for what she called her “AWTHRITUS” made her face puffy. She did not attempt to mask these cosmetic casualties of illness. In the photograph, her dark hair is cropped and thin at the crown; her gaze is fixed beyond the viewer. She appears serious and masculine, save her painted lips and the gathered neckline that peeks out from beneath her dark jacket. She is partly bald and baldly assured.

But of what, exactly, is she assured? O’Connor’s innate sense of her artistic talent and her strength of self-possession are well documented. Most biographical portraits of her recall how, at age 24, she coolly defended her work against manipulation by John Selby, an editor at Holt, Rinehart. The publishing house had, by way of a fellowship award in the amount of $750, secured a first option on Wise Blood. “Selby and I came to the conclusion that I was ‘prematurely arrogant,’” O’Connor wrote to Paul Engle, her mentor and the director of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. “I supplied him with the phrase.”

I am most certain of this: she did not believe the photograph would be the first of many to establish her literary identity as an invalid.

Her conviction in her abilities as a writer was well nourished, both at Iowa and by her Yaddo connections. But it is not difficult for me to imagine that she also felt a more basic sense of conviction: that, in winter 1952, after a period of convalescence during which she concentrated on regaining her strength, finishing her book, and raising “twenty-one brown ducks with blue wing bars,” she believed her health would stabilize enough to allow her return to the intellectual comfort of her northeastern literary sphere. She probably thought her hair would regain a luster commensurate with its young age. She thought, in all likelihood, she was documenting a mere moment of strife in a healthful writer’s life, a physiognomy as temporary as her Georgia sojourn, and this only by way of an obligation to her publisher. She was too naïve, then, to consider declining Harcourt, Brace’s request for an author photograph, though she resisted as best she could, sending the final selection a full month after it was requested. I am most certain of this: she did not believe the photograph would be the first of many to establish her literary identity as an invalid.

. . . as if a woman must balance intelligence with prettiness to be legitimate.

— Hilton Als on Flannery O’Connor

The physical consequences of her illness haunt O’Connor’s legacy. From the publication of Wise Blood onward, she begrudged the camera lens, even as she allowed it on her property, a two-story farmhouse edged by a dense forest of loblolly pine, sycamore, oak and poplar trees. Photographers arrived occasionally, from Atlanta or New York, to capture the author at her typewriter or communing with the peacocks she raised. The resulting images, often printed alongside her own essays and short stories in Catholic papers and secular magazines, betray her body’s frailty, which is perhaps why O’Connor rarely believed printed photographs resembled her. “Most [pictures] don’t look much like me,” she wrote in the last year of her life. “Or maybe they look like I’ll look after I’ve been dead a couple of days.”

Yet few who write about O’Connor refrain from mentioning these images or her photographic appeal. The subject has been batted about by critics, who cite her prematurely aged face and aluminum crutches as origins of her grotesque fiction. “Hopelessly sick, bald, and deformed, she writes with a vengeance,” said one reviewer of Everything That Rises Must Converge. Others have engaged in revisionary commentary. Katherine Anne Porter declared that O’Connor, whom she knew personally, was merely ugly in photographs. “She was very slender with beautiful, smooth feet and ankles,” she wrote to a friend after the author’s death, in 1964. Mary Gordon discussed O’Connor’s appearance despite the effects of illness, calling hers “a peculiar face for a writer” in a 1979 review of The Habit of Being. Gordon went on to say: “No face could appear less fashionable or stylish than Flannery O’Connor’s.” And, “It does not seem a writer’s face; rather that of an aunt more educated than the rest of the family.”

Gordon went on to say: “No face could appear less fashionable or stylish than Flannery O’Connor’s.” And, “It does not seem a writer’s face; rather that of an aunt more educated than the rest of the family.”

In 2015, the U.S. Postal Service unveiled a ninety-three-cent stamp featuring the writer’s college-era countenance, unperturbed by the cat-eye glasses that became, along with the crutches she used, her photographic signature. “Wait — What’s Betty Crocker doing on Flannery’s stamp,” wrote Lawrence Downes in the New York Times. He argued that another image would have better represented the author on postage: one she had painted herself.

My daddy said I was a different breed of dog from my brothers and sisters. ‘You know,’ Daddy said, ‘it’s some that can live their whole life out without asking about it and it’s others has to know why it is, and this boy is one of the latters.’

— The Misfit in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find”

I spent roughly a year wondering, often in specialty doctors’ offices, what was wrong with me. Then and for some time after, I avoided being photographed. I escaped to the parking lot behind my office building to get out of a group portrait, the purpose of which I never learned; I ignored the woman from human resources who asked me to provide a headshot for a staff database. Eventually, she arrived at my desk with an iPhone and got her picture. Photographic proof of the Christmas I spent in Nevis, in 2012, does not exist, and, maybe because my memory is most often jogged by pictures, I barely recall being there. Avoiding cameras coincided with a conscious altering of my overall aesthetic. I tore through the closet I kept in my mother’s house, which was by then stocked with the clothes I had initially left in Savannah, and I cast out what struck me as feminine — a preemptive declaration of my physical incongruity with anything that might be considered pretty. I did not possess O’Connor’s biting wit, but I recognized power in saying first, through a plain, mostly black, androgynous wardrobe, what I thought others believed. I earned validation for my efforts one night, while sitting at a bar with a colleague who said, unprompted, “You know what I love about you, Caroline? You look like you just don’t give a fuck.”

I did not possess O’Connor’s biting wit, but I recognized power in saying first, through a plain, mostly black, androgynous wardrobe, what I thought others believed.

An air of not giving a fuck is, incidentally, what some have said they love about Flannery O’Connor. Though mainstream feminism has often ignored her work, she has earned praise for her lack of vanity, for her unwillingness to compromise by . . . what? Sweating under a wig in rural Georgia? Bumbling around her farm without her glasses? Amid her birds and her mother’s cows she had no reason to take uncomfortable beautifying measures. Perhaps her country life aided her sense of humor in protecting her esteem. When visitors did arrive with cameras, perhaps she did not feel as alien as some people assume she must have.

I did ultimately receive a diagnosis, in the spring of 2013. My condition was of the autoimmune variety, a disease called Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, in which the body attacks the thyroid and produces erratic fluctuations in the relative hormone levels. (This is why the disorder can be difficult to detect.) It is chronic but somewhat manageable with medication. My relief upon receiving this news was marred by a feeling of ridiculousness. “It’s really not a big deal,” the diagnosing doctor told me. But watching my body mutate from my perception of myself — measuring a daily deterioration by the number of strands I held in my hands after stroking my hair or the length of time I could stand without the aid of an inanimate object — had felt like a big deal. I was too embarrassed to tell him that. I began taking the medication and lopped my hair to my ears. I continued to look like I didn’t give a fuck. Five years after discovering the banality of my affliction, I maintain my simple, unfeminine wardrobe. I have trained myself to resist complaining on days when I feel tired or wake up hollow-eyed or monitor an angry flush ascending my neck or tracing the claw of my ribcage.

“It’s really not a big deal,” the diagnosing doctor told me. But watching my body mutate from my perception of myself, had felt like a big deal. I was too embarrassed to tell him that.

When my phantom illness found a name, I found myself unable to say it. The disease and its accompanying symptoms aligned with my physical experience, but the diagnosis somehow felt insufficient. In accounting for the various malfunctions of my body, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis undermined the psychic impact of experiencing that body in revolt. My disease was not serious. It was no big deal. I no longer had the right to cry when I looked in the mirror. I did not wish for a sorrier fate, but the name of my own was not enough to explain the leveling of my morale or, as I had come to believe, the weakness of my character. I kept reading O’Connor, searching her letters and her fiction for confirmation that sickness had damaged her spirit, too. I wanted proof of a twin wound and a model for mending it.

I painted me a self-portrait with a pheasant cock that is really a cutter.

— Flannery O’Connor

A cousin of O’Connor’s maintains the original in a private collection; but a reproduction hangs above the sofa in the living room of the Milledgeville farmhouse where O’Connor lived until her death. She completed the portrait in the summer of 1953 as a clever corrective to the ravages of ill-health and, I think, the Wise Blood author photograph she hated. In my mind, she was rebelling against that black-and-white picture and the terminal truth it captured; she was attempting to redefine her authorial image by her own hand. Her artistic training as a cartoonist for her high-school and college newspapers informed her. She used a palette knife, because she didn’t like to wash the brushes, and painted herself wearing a large sunhat and holding a pheasant. “I am the one on the left,” she wrote to a friend. “Of course this is not exactly the way I look but it’s the way I feel.” At the time, O’Connor was still injecting herself with shots of cortisone, “which gives you what they call a moon-face,” and her hair remained thin. She did not consult a mirror or the pheasant as she painted. “I knew what we both looked like,” she wrote.

I kept reading O’Connor, searching her letters and her fiction for confirmation that sickness had damaged her spirit, too. I wanted proof of a twin wound and a model for mending it.

When viewed at a distance (the best way view it, according to O’Connor), the self-portrait appears to depict a young farm boy. But up close, and taken individually, parts of the painted face appear familiar: the sharp eyebrows and Cupid’s-bow lips, a short tuft of hair flipped over an ear at an insubordinate angle. O’Connor rendered herself and her bird in bold colors and a flat Byzantine perspective. Against a streaked green background, she wears a red blouse and a black jacket, mirroring the shades of her companion — black head with a mask of red spreading from his triangular beak. Both gaze directly and defiantly at the viewer. “I like very much the look of the pheasant cock,” she wrote, ten years after its painting. “He has horns and a face like the Devil.” In her writing and in her life, O’Connor’s transcendent theme was divine grace, or, as she put it, “the action of grace in territory held largely by the devil.” Perhaps, then, it is not a stretch to view the painted sunhat atop the boyish head, the spiraling tones of yellow and gold, and consider it a kind of malformed halo.

Upon completing the portrait, O’Connor campaigned to have it serve as her author photograph, sending it first to Harper’s Bazaar, where an editor called it “a little stiff.” She mailed snapshots of it to her friends, to her literary agent, and to at least one reader who had asked what she looked like. Eventually, as she wrote to Elizabeth Hardwick and Robert Lowell, “I got tired of having people say it didn’t look like me as I knew better it did. So I got a lady with a flashbulb thing to take me alongside it.” In this photograph, which O’Connor was pleased to send to doubting friends, she stands shoulder to shoulder with her painted self, lips pursed and hair chopped to an unruly length.

In 1955, she sent a photograph of the painting to her editor, Robert Giroux, and asked that he consider it for the back of the book jacket for A Good Man Is Hard to Find, her first story collection. “If you have to have one,” she wrote, “I think it will do justice to the subject for some time to come.” Giroux gently rejected the idea. The book published without an author photograph, a fine concession, in her opinion: “It is nice not to have to look at myself on the back of the jacket,” she wrote, upon receiving her first copies. None of her subsequent books appeared with an author photograph.

If O’Connor entertained the theme of divine grace in her self-portrait, she would have done so only after pointing out her efforts towards realism.

In her fiction, O’Connor’s patience for symbolism was activated only after realistic elements were established. Of her devotion to the concrete realm, she wrote, “Fiction begins where human knowledge begins — with the senses — and every fiction writer is bound by this fundamental aspect of his medium.” Mystery could only emerge after hard realities of life had been satisfied and characters had been fully rendered. The Misfit, in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” had to be a criminal before he could assume a prophetic guise. The image of the Holy Ghost in “The Enduring Chill” had to be a water stain before it could rip Asbury from his narcissistic delusion. The girl in the waiting room in “Revelation” had to be an irritable teenager before her ugly outburst could reflect the hypocrisy of Mrs. Turpin’s soul.

If O’Connor entertained the theme of divine grace in her self-portrait, she would have done so only after pointing out her efforts towards realism. And yet, if nothing else, the painting was personally symbolic — it’s the way I feel. It is the writer and one of her birds. It is also the writer, moon-faced and faithful, clutching sin with one hand and reflecting its colors with her own. It is the way she felt and the way she wrote.

Where you come from is gone.

— Hazel Motes in Wise Blood

Before he blinds himself and begins lining his shoes with stones, before he wraps barbed wire around his torso, Hazel Motes preaches the word of nothing from the hood of his rat-colored Essex. O’Connor’s orthodox Catholic faith instils an absurdity into this scene that my mind, despite its atheist conceptions, can appreciate. I read the vibrant, darkly comedic words of a woman whose mortality echoed in every ache and fever, whose daily life was subject to the whims of her malady, and I laugh with her. My hair continues to fall and grow and fall again. Sometimes my fingers scream when I type. Living inside a body I’m only just beginning to recognize becomes easier amid stories crafted by what sickness could not contain. I do not understand what it means to exist under a threat of death, but I’ve felt the emotional burden of trying to live in the shadow of illness. Far away from my mother’s house and the constant call of warm baths, I feel it still.