Interviews

What Happens When You Throw Literature Into the Large Hadron Collider?

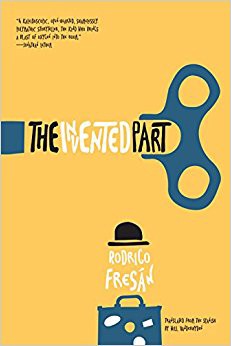

Particles, people, and literary references collide in Rodrigo Fresán’s ‘The Invented Part’

Let’s begin by talking about the Large Hadron Collider. It’s a particle accelerator located in Switzerland. As its name suggests, it’s massive. Its research may well help humanity determine certain essential properties of the universe in which we live. And, for numerous science fiction and disaster-story aficionados, its very existence opens the door to a host of tales of science gone wrong and the earth itself being consumed in a storm of anti-matter. (The BBC docudrama End Day, made by a pre-Rogue One Gareth Edwards, memorably depicts this; it’s got plenty of nightmare fuel in its imagery of the world imploding.) There is, in fact, a website dedicated to answering the question, “Has the Large Hadron Collider destroyed the world yet?” As of the writing of this review, thankfully, it has not. Still, its allure to storytellers isn’t hard to understand.

Rodrigo Fresán’s 2014 novel The Invented Part, newly translated into English by Will Vanderhyden, is a book that deals with the implications of the Large Hadron Collider on humanity and the universe. It’s also a tale of a lonely and frustrated voice grappling with their isolation from society, in the mode of William Gass’s The Tunnel and Saul Bellow’s Herzog. It’s a strange and rewarding book, and one which channels a stylized, almost hermetic environment—which seems to fit the themes of both supercolliders and the inner workings of the human psyche.

The Invented Part opens with a whopping sixteen epigraphs—musings on writing, memoir, and veracity from the likes of John Cheever, David Foster Wallace, Marcel Proust, Bob Dylan, Michael Ondaatje, and Iris Murdoch. First and foremost: that’s a lot of epigraphs. But by the end of the opening section in which they appear, Fresán’s intention for them seems clear—there’s a sort of micro-narrative taking place over the course of these sixteen quotes, one which establishes a realm in which quotes from venerated authors create an irreverent dialogue. For example, Kurt Vonnegut’s “All this happened, more or less” is immediately followed by James Salter’s “Nothing actually happened.” Epigraphs are frequently used as a way to usher the reader into the thematic ground that the ensuing book will explore. Here, Fresán is up to something a little different: the collage-like effect of these quotes provides a preview of what to expect from the novel to come. In other words, it’s the epigraph (or epigraphs) as overture.

If this sounds contentious, odds are good that the narrator of The Invented Part—and maybe the book itself—agrees with you. Once we’re past the epigraphs, the narrator (called the Boy, the Young Man, or the Lonely Man) veers into a section musing on fictional beginnings. From an early moment, the narrator takes aim at a particular mode of reading.

Today’s electrocuted readers, accustomed to reading quickly and briefly on small screens. And, yes, goodbye to all of them, at least for as long as this book lasts and might last. Unplug from external inputs to nourish yourself exclusively on internal energy.

This all might seem a little overwhelmingly “get off my lawn,” but that’s intentional—a fictional character feeling alienation rather than a novelist striving for the same. In the hundreds of pages that follow, the story of this novel’s writer-protagonist manifests in a host of forms, from archetypically-told tales of the artist as (literally) a Young Man to sections in which Fresán uses different fonts to convey the collisions of different narratives. The narrator of The Invented Part abounds with contempt for technological alterations to the experience of reading, and yet his story is being told in a manner that seems half Modernist and half hypertext.

What follows is a life told in fragments, showing the novel’s central character at a host of points in his life, from heady and idealistic youth to the more jaded voice encountered earlier in the narrative. There’s also an abundance of references to other artists — not just writers (though Joan Vollmer, Charlotte Brontë, and F. Scott Fitzgerald are the subject of plenty of rumination throughout the narrative), but also musicians. Which is another point at which the narrative folds back on itself. At one point, a comparison is broached between songwriting and fiction, which leads into this long digression:

Do any of you have even the slightest idea who Harry Nilsson was or is? Or Warren Zevon? And, just to be clear, I’m not talking about their dissonant or clever self-destructive epics but about their constructive intimacy in the moment of composing subtle and perfect songs.

As the novel goes through its abundant permutations, themes of the cosmic, the weird, and the science fictional start to enter the narrative. In the span of two sentences about two-thirds of the way through the book, Fresán invokes 2001: A Space Odyssey, H.P. Lovecraft, Jorge Luis Borges, and Adolfo Bioy Casares. Here, you have the transcendental, the paranoid, and the bizarre all invoked in short order—all of which serves as a notification for Fresán’s final gambit.

By the end of the novel, this narrator’s destination is in sight: the Large Hadron Collider, where he hopes to turn his metaphysical debates into something much more cosmic, and remake the universe. Given that the previous five hundred pages have found our hero dissecting his own life using a host of fictional devices, it doesn’t seem too far off the mark to note that The Invented Part is its own kind of “clever self-destructive epic.” And while writers writing about alienated writers is a familiar sight, there’s a welcome distancing here, as Fresán’s literary invocations remind the reader of the dangers of an unchecked creative ego.

Perhaps in keeping with the book’s science fictional side, The Invented Part is the first volume in a planned trilogy; Fresán’s followup, The Dreamed Part, is due to appear in English translation in 2019. This is a head-spinning novel, one in which heady invocations of art abut the loose outlines of a plot that could well serve as fodder for a SyFy original movie if treated differently. But then again, that blend of intense aesthetic discussion and absurdist pulp plotting is one that constantly reassembles itself, and offers a read unlike little else that’s out there. In terms of its knowing merger of pulp science fiction tropes and rigorous musings on art and society, the work of Bhanu Kapil is one of a handful of points of comparison—but Fresán and Kapil are very different writers. The Invented Part is a surreal and circular narrative, eventually cycling around and colliding with the very story it’s telling. As images go, that seems entirely fitting.