interviews

What if Aliens Destroyed Humanity by Solving All Our Problems?

In Chana Porter's "The Seep," a gentle alien invasion makes humans healthy, happy, and compassionate

How would you prepare for the end of the world? Chana Porter would throw a dinner party. At the beginning of The Seep, her protagonist Trina FastHorse Goldberg-Oneka hosts a gathering with her wife Deeba as the disembodied alien entity “the Seep” gently infiltrates the world’s water supply. Fast forward several years, and the Seep has solved all of humanity’s problems. No one is hungry or sick. No more wars are fought and no one ever has to die. The planet is healed and the Seep makes all beings, human and otherwise, deeply aware of their connection to one another. Best of all, Seep technology makes anything possible. Deeba decides to erase a traumatic, pre-Seep childhood by regressing to infancy, to start her life anew. When Deeba asks Trina to become her mother instead of her wife, Trina is devastated and the two part ways.

As Trina wrestles with grief over her wife’s decision, her perspective on the Seep and the nature of its benevolence changes. When she encounters a boy who has, until now, lived apart from the Seep, Trina sets out to rescue him from the perils of their utopia.

Chana and I met at a dinner gathering several years ago, and despite some apocalyptic natural and political events since then, the world perseveres. That night, we discussed weird fiction, climate change, and Houston restaurants. I have been inspired by her vision ever since. Though The Seep is her debut novel, Chana is a playwright, a MacDowell fellow, and co-founder of the nonprofit The Octavia Project. We spoke over the phone about grief, snack cakes, and how the end of the world might spark new beginnings.

Charlotte Wyatt: I was going to start by asking about utopian tropes and how they influenced you, but I think we have to start with food. The novel is bookended by instructional tips for dinner parties. There’s subtle religious imagery throughout, in how food is communal. First contact with the Seep is through ingesting it. How do you understand the role of food and eating throughout The Seep?

CP: The food is incredibly important to me, and it’s something I think about a lot. When I read a book and pages and pages go by, and no one’s even mentioned getting peckish and eating a banana, that seems very strange to me. I try to write from an embodied place. Food is culture, and food is community. Food is family. So there’s all those things about how we take care of one another, how we take care of ourselves.

And at the same time, I think I use food to underline this very amazing, complex thing about being a person, which is that we like to eat things that aren’t good for us. It was funny to me as I wrote, and I found people in my story talking about what they missed from the past, in pre-Seep time before they could feel everything—like let’s say you hold a banana. You bring it to your mouth, and through the Seep, you’re not just tasting the sweet flesh, you’re feeling if pesticides were put in the ground while these bananas were being grown, and the harm that did to the microbiome. And whether or not the people who are growing and picking the fruit were underpaid or enslaved, or if they were allowed bathroom breaks. You’re tasting the petroleum these bananas are being shipped by. You’re tasting all of the social, environmental, and emotional costs at the same time. It really changes what we can put into ourselves. And it’s just so funny—I mean, I think about the things that I feel nostalgic for, like Little Debbie chocolate cakes. Zebra Cakes.

CW: Oh my God, yes!

CP: I’m very aware that they taste like artificial, chemically processed waxy black plastic. And yet! And I haven’t had one for a very long time. I think it’s such a funny puzzle that we can be attracted to things that are not only toxic, literally, for our bodies, but the environmental cost of them, too. And the social and political costs. Like, who makes these? We think that we deserve very cheap food in America. We spend less in America for food than most people in Europe do, and the hidden costs of those foods are being wreaked on our own bodies, which is another form of environmental racism.

CW: Even in the utopia that’s created by the Seep, there are characters like Trina who are abusing substances. Was that abuse something you were interested in exploring in the book?

CP: I don’t think I sat down one day and thought, I’m going to explore some substance abuse. I’m very keen on the ways we try to silence or escape the way we feel. I think Trina, making the choice to use alcohol to be self-destructive—while it’s not the most graceful choice, I do think there’s something valid in that choice. Because she’s in this culture, partially through the Seep but supported by all the people around her, where they want her to let go of pain. And she is finding value in pain. Part of the value I think she finds throughout the course of her grief was that she was part of a very beautiful and very meaningful relationship, for a long time. And to use a balm to soothe that without really mourning I think would be a disservice to its memory. She does spiral. There is a messy kind of falling apart, and I’m not trying to validate her substance abuse. But I do think she is pointing towards something—”I don’t want you to take away my pain. I want to spend some time in my pain. Don’t try to find meaning for me. Let me be lost for a time.” That’s a dark and a hard journey, but I think it’s a valuable one.

CW: Her grief feels very much at the heart of the story. People are grieving for the broken world that existed before the invasion, and that leaves them feeling conflicted. But Deeba’s decision to be reborn through Seep technology also stems from grief, albeit a different kind. There are lots of specific ideas about grief in the book. What does grief mean to you?

CP: Octavia Butler wrote, “God is change.” I really resonate with that. And also, I’m not into it!

There’s a beautiful, tender pain in the fact that everything changes, everything dies, nothing is permanent.

CW: Oof. Yeah, I get that.

CP: There’s something so human about how we’re these creatures of great dichotomies, where we want to cement and gather and hold on to things. When something’s great we want it to never stop. And there’s a beautiful, tender pain in the fact that everything changes, everything dies, nothing is permanent. Have you ever felt the very strange feeling of getting something you always wanted, only to find out you’re no longer that person? You don’t want it anymore. The way we can’t even depend firmly on our own dreams, our own likes, our own emotions. Things are always in flux. All we have are these very tender, present moments, where we have to be supple and share and be curious about the unfolding of now. It’s very hard, because, I think, we are drawn to, and to some degree supposed to, commit. Commit to our dream. Commit to other people. Commit to community. Commit to building a home. And that push and pull of “I want to strive,” and “I want to plan,” and “I want to invest in you and in me and in this home that we’re making,” and at the same time, you can’t make a promise for your future self. It’s not actually possible.

CW: I feel this is an important place to say the book is also very funny! There’s something whimsical about it that reminds me of Terry Gilliam’s film Brazil, but the negative of Brazil. Instead of horror rooted in absurdity, there are joyous moments. Like a foot chase interrupted by a passing topless unicycle collective. Were you consciously bringing humor into the book?

CP: I am not interested in exploring, or spending time with characters that have zero sense of humor. I think that the world is funny, and absurd. I think recognizing humor is one of the really wonderful things about being alive. All of my work, be it novels, plays—they will always have not just the jokes, but I want to spend time with characters that have senses of humor about the world and themselves. I think that is a distinctly wonderful thing about being human.

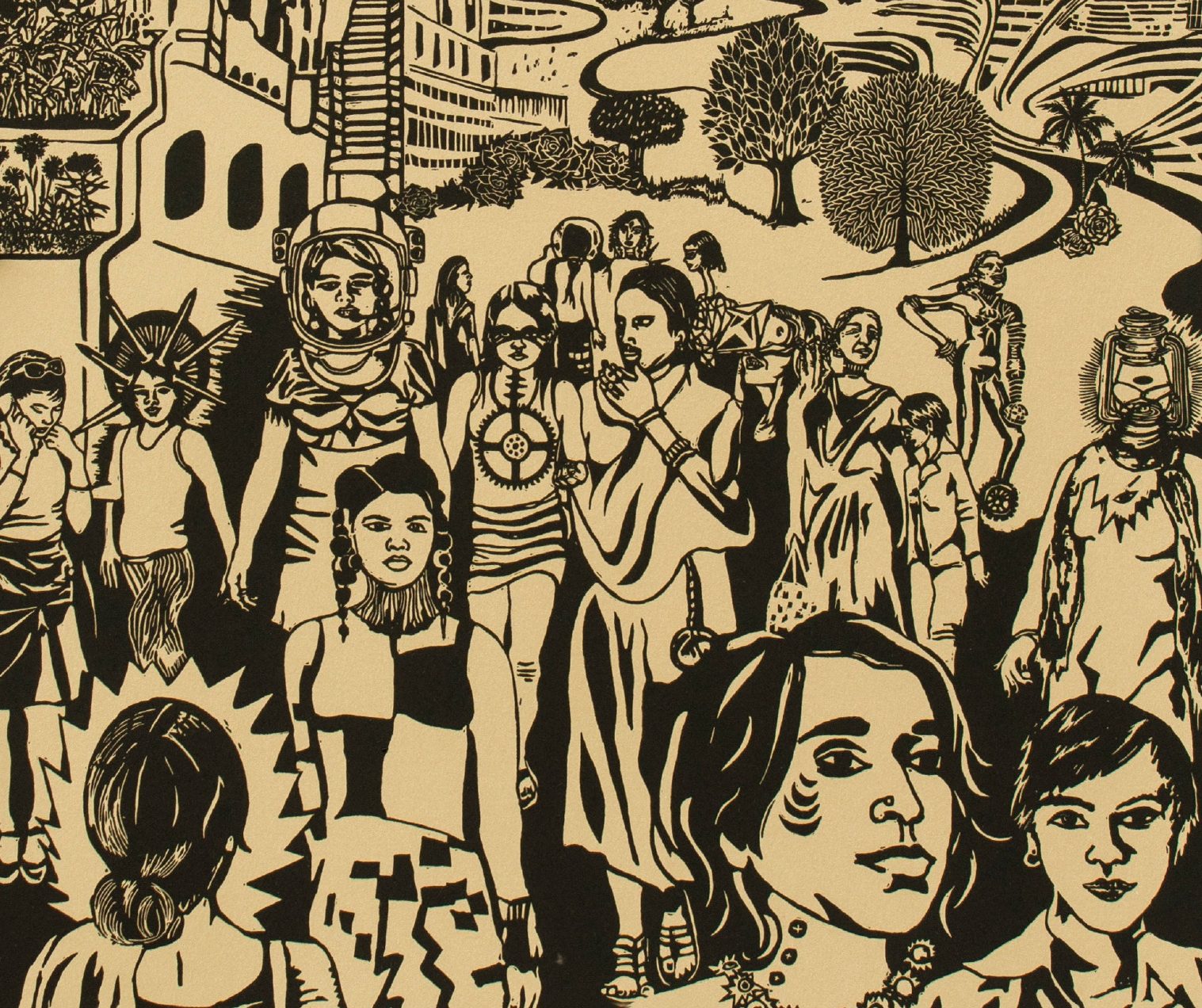

CW: In addition to your own writing, you cofounded The Octavia Project, a nonprofit that offers workshops to traditionally underrepresented voices in science fiction, especially young women and non-binary youth of color. Did that work influence your choice to write a protagonist who is a trans woman?

CP: I was already writing the book before the Octavia Project, which I started with Megan McNamara in 2014. At that time, I was just starting to get how much energy, money, space, time, and belief is required to take your book from an idea in your brain to something being published. So I really think we need the powerful imaginations of girls of color and non binary youth from more fragile communities, and that our world will be significantly poorer if we do not invest in these narratives.

I started writing The Seep the year before that, in a graduate program at Goddard College. At that time it was a massive novel, with shifting multiple points of view. Trina had been one of three named characters. I write from a very intuitive, gut-based place. I didn’t sit down and think, I’m going to write a book with a trans protagonist. But I did write a book with one trans protagonist out of three. And as I wrote and rewrote, it became clear that Trina’s story about loss, and about grief, was the most compelling way for me to explore all these other themes about change, but also about racism and identity.

I went to Goddard college because I wanted to study with Rachel Pollack, who is the planet’s foremost Tarot scholar. I had originally met her through Tarot. She wrote this amazing, spiritual sci-fi, where she explores bureaucracy in a way I found really smart. (People who don’t know should go read Rachel Pollack’s Temporary Agency and Unquenchable Fire. She is so smart!) Rachel is in her 70s now. She’s a trans woman and she’s a “tryke,” as she lovingly puts it, a trans lesbian. It was really nice to be working on the book with her as my mentor. And getting closer and closer to [understanding] Trina really does need to be the main character, allowing the other plots to kind of fall [into place]. And then having this mentor who’s very much a trans pioneer. So she’s our elder. She was an amazing person to guide me, not just through that stuff, and the talking about identity, but she helps me so much. She’s very responsible for the creation of Pina [Interviewer’s note: Pina is a waitress at a diner in the novel, and she is also a bear.] She was the one who was like, “Chana, I think you’re being too human-centric. How is the Seep affecting other beings?”

CW: Pina’s song is definitely—I want to avoid spoilers, but quickly: Pina’s song was the moment where I burst into tears. It feels so intuitive now, looking back on it. Of course every animal has songs they would write. But, back to Trina: she also talks at one point about her heritage, both Native American and Jewish. Both are important to how she arrives at the end of the novel. Why were these specific identities important to you?

CP: I wanted to parse through and explore how, sometimes in utopian or dystopian sci-fi and fantasy, race is not addressed. Fantasy and sci-fi can whitewash people. And because the Seep wants to heal and make everything abundant, healthy, happy, there can be this whitewashing of past trauma, of past inequality. So I chose to make her both Native American, and Jewish, one to acknowledge—for indigenous people of America, there’s already been what, you know, anthropologically would look like an Apocalypse. You could frame these things as: this is already a dystopia. I wanted there to be a very strong component of the text that would underline that, and that Trina would stand and say, My story is valuable, my past is meaningful. [My] history is not interchangeable. And there’s meaning in acknowledging. Native American and Jewish identities sometimes get whitewashed. And so you have Native American displacement and genocide, and then you have the Jewish, not just genocide but also diaspora, where I think it can be very easy to assimilate. Which eventually becomes just white supremacy. So I was really intrigued by having Trina both being from the occupied lands we’re standing on now, and then in another way, being someone without a home.

CW: This next question feels silly by contrast but I’m going to ask it anyway: The starred review of The Seep in Booklist talks about human contact with the Seep as mimicking the sensation of being drugged. That Seeped humans “experience benevolence and serenity.” How do you imagine contact with the Seep would feel?

I hope something about this book will help us to imagine the planet as one great body.

CP: In my twenties, I did a fair amount of psychedelic drugs. Then I got into meditation, and I found out that I didn’t need to take drugs. I found out through the brute power of meditation, and spending time with my own brain, I could get myself to these feelings of peace and interconnectedness and beauty. The Seep is very much a metaphor for consciousness. I think it’s actually something that’s available to us now. I think that we could use the power of our minds to think about the choices that we’ve made, and the choices that we continue to make. There’s a really nice tweet I just saw, something like Nestle says they can’t provide us chocolate at these low prices without slaves. And it’s like, well, if we can’t have chocolate without slavery, maybe we shouldn’t be eating chocolate.

I think that the hidden costs of things is something we’re very much bringing to light now, in terms of environmental costs and climate change. It’s something that will be, I think—like “the ways that the sausage gets made,” it’s going to be harder and harder to turn a blind eye to that. I’m really grateful about that, because I do not want my clothes made by enslaved people and children. I do not want them made with cotton that has been so heavily genetically modified and covered with pesticides that are impacting the environment. I don’t want my food grown by farmers that are killing themselves because they’re so in debt. I think the Seep, in terms of being a euphoric feeling of interconnectedness, is something we can feel now. And I think the pain of that is true, too, and is something that we need to feel.

I’ve been doing this practice where, whenever I do something nice for myself—like yesterday I took a bath. And I thought about the water and how good it felt. And at the same time, I was thinking about being a migrant in our country today, being in a concentration camp. And both of these things are happening at the same time. I am in a bath, and I’m enjoying my bath. And there’s someone in our country, now, probably in our state—definitely in your state—who is being held away from their child. Who is being refused clean water. Who is sleeping with the lights on.

I hope something about this book will help us to imagine the planet as one great body. And that every single thing we do does come back to us, and does touch us.