Books & Culture

What Sam Shepard Taught Me About Gods, Dads, and Death

He was the swaggering, sexy cowboy genius whose work helped me find myself

I like to think that Sam Shepard would have approved — or, at least, disapproved in a deeply sympathetic way — of the fact that I started reading his work because of my dad. Shepard’s plays are, like so much canonical mid-to-late-twentieth century American theatre, just full of dads: horrible, mythic dads, dads as original sin, dads striding Zeus-like across the landscape, everywhere dads. Shepard was, both by his own admission and in the myth that grew up around him, influenced by his own father, a raging alcoholic who named his son after himself and who disappeared and reappeared like some kind of vengeful, absent ghost throughout Shepard’s childhood. His father haunts his work like a shittier version of Hamlet’s dad, showing up again and again in one form or another across more than 40 years of published work.

A perhaps apocryphal story goes that one of Shepard’s plays, probably Buried Child or Fool for Love, was staged somewhere out west, near his dad’s old stomping grounds. An older drunk man, seemingly a town local, bought a ticket and sat down in the front row. During a monologue by the character based on Shepard’s father, the old guy started talking back to the character. “Sam,” he yelled “you’re a fucking liar, and you’ve always been a liar! You always said that, but it was a lie!” He then vanished into the night, muttering, and although no one could ask him, it was easy to assume that this man had known Shepard’s dad, and that the facsimile on stage was so close to the truth that seeing the play had resurrected some long-standing argument with the older Sam.

Support Electric Lit: Become a Member!

I doubt the veracity of this anecdote only because it’s too perfect; it seems like something that might happen inside of one of Shepard’s plays. But it also captures the legend that swirled around Sam Shepard, how difficult it is to untangle the influence of his writing from the legend of his life, and why it might be unnecessary to try. Sometimes it’s best to believe the story even when you know it probably isn’t true, and sometime it’s useful to let someone like Shepard exist as something larger than a human individual. Perhaps what seems most devastating to me about Shepard’s passing is that I never thought he could die, because I never quite believed he was real.

This blurring of reality and fiction is a lot of what made Shepard famous, and a large part of what gives his work such a runaway, addictive quality. It’s one reason why so many writers who read his work when we were young and impressionable felt that it cracked something open, that it offered a new and heady kind of permission. One of the points of celebrity is that we are all looking to make gods for ourselves. Another way to say this, of course, is that we’re looking for dads. We want figures whom we can claim as our own origins, in the way traditional conceptions of the family allow children to narrate their identities out of the story of who their parents are. This desire for precedence is why some of us invent our parents as figures larger than human, and is perhaps also why many of us turn to artists or public figures — and Shepard was both, even if he didn’t always want to be the second one — as influences by which we can define our identities. From what they represent, our ideas of ourselves can be born.

One of the points of celebrity is that we are all looking to make gods for ourselves. Another way to say this, of course, is that we’re looking for dads.

It’s hard to talk about Shepard because he ends up sounding like a parody– this swaggering, sexy cowboy genius who wrote like Samuel Beckett if Beckett had gotten high on LSD on a road trip across the American West, this extraordinarily fuckable hobo with his evil father and his mysterious past, who played in bands and had relationships with both Patti Smith and Jessica Lange, who had hung out with Bob Dylan but also wrote plays that fit easily into the same pantheon with Williams and O’Neill. A figure this outsize inspires a religious sense of devotion, and all gods act as a crutch for the people who choose to turn to them. Not in the sense of holding us back, but that their existence, their example, allows us to get somewhere we wouldn’t have been able to go without their influence.

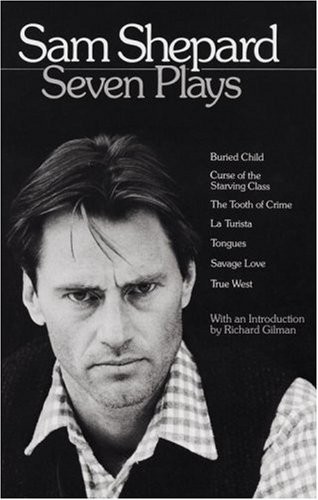

Anyway, I found Sam Shepard’s plays through my dad, who was born in 1950s and lived in New York in the ’70s and ’80s and, like a lot of intellectual dudes of that same age, thought of Shepard as the be-all and end-all of American masculinity, thrilled that someone could be manliest strong silent cowboy in the world and also win the Pulitzer Prize. My dad had copies of almost all of Shepard’s published plays in our house when I was growing up and, because as a kid I was constantly trying to fast-forward myself into adulthood by reading things that adults liked to read, I picked up Buried Child one day, and in very quick succession, at around age fourteen, read everything else Shepard had written.

I had never been to the American West, had never been drunk, had never had a fight that involved real physical violence. I had never experienced any of the emotions or situations, the grand and awful things, with which Shepard grappled in his plays. And yet I found them to be exactly what I needed at the time, unsettlingly and necessary and generative. I was looking for art that was the opposite of myself. Shepard’s work spoke to a desire to access something uglier than my reality, something where all the yelling happened out in the open. It offered a landscape, both literal and emotional, that matched the roiling emotions I carried around inside myself, emotions I still thought I couldn’t share with anyone else. (One of the joys of adulthood, of course, is discovering the many, many, many people who got into writers like Shepard around the same age I did because they felt exactly the same sort of emotions).

In this way, Shepard’s work was sort of like pop music. People imagine that because pop music is marketed to teenagers, it must be about the teenage experience, but as actual teenagers we listened to pop music not because it was about us, but because it pointed toward an imaginary future we hadn’t experienced yet. Often we like art not because it speaks to our experiences, but because it opens up our ability to imagine future experiences. It creates a preparatory and hopeful emotional landscape, a map of places we have not yet been.

Pulitzer-Winning Playwright Sam Shepard Has Died

When I first encountered Shepard’s writing, I was looking for things that said I could be big in a world that, both literally and figuratively, constantly urged me to be smaller. I was looking for monstrous, capacious work with a bottomless appetite, for a vision of a world that was expanding rather than shrinking. Shepard’s landscapes and his people were one and the same thing. Many of his plays were ostensibly about, or at least set in, the American West, but what gave them such a sense of expansion was the humanity of the characters within them, rather than the size of the country. Shepard was the writer who showed me that characters could speak in pure emotion, and that just two people in a room together could be electric, could be an entire world. The way in which the landscape inside and the landscape outside became one and the same echoed what I would later connect with when I discovered Melville — writing in which the vastness and weirdness of the country was just a way to get at the vastness and weirdness of the human beings in it, caged in their relationships and their rooms and their bodies, howling that frustrated vastness into the edge of an endless desert. His plays confront the enormity of trauma and of grief, which is why they’re often also very bleakly funny — these emotions are too large, too inconsolable, to stay within the bounds of logical expression. His writing offered the idea that these worst, weirdest, ugliest human emotions were how we break free from the smallness of ourselves and our lives, how we break into the vast landscape looming out beyond us in the night.

When I first encountered Shepard’s writing, I was looking for things that said I could be big in a world that, both literally and figuratively, constantly urged me to be smaller.

Shepard once described romantic love between men and women as “basically impossible.” His work posits that most human relationships — not only romance, but family and friendship and all attempts to be close to one another — are fractured and unfeasible, an experiment that fails over and over again. Yet when I come back to his plays as an adult, they seem more than anything to be about forgiveness, despite their depictions of our human failures to be good to one another. That very admission of impossibility, of the brokenness of our attempts to know one another, and the fact that Shepard presents this without pretending to offer any answers, is perhaps why his work ultimately seems to radiate forgiveness. It’s also what is both devastating and comforting about his death.

Shepard was enormously influenced by Samuel Beckett. Both men were writers who set up shop up right against the omnipresence of mortality, and the total absence of answers that mortality carries with it. They were both writers willing to put up a fight against the bleakness of existence, while knowing from the start that they would lose, that the point of the fight was its inevitable loss. An old friend of mine works as a doctor at the VA out in a part of the country where a lot of Shepard’s plays take place. She once described how her relationship to death had changed over a few years on the job: “It used to be a fight with a mortal enemy,” she explained, “but now it’s more like a pick-up game with an old buddy.” That casual pick-up game with death was what both Shepard and Beckett were writing: a ferocious game, but one full of the acceptance of loss, the open and forgiving acknowledgement of futility. Maybe the greatest forgiveness is admitting that one does not have any of the answers, that there is ultimately nothing to be done.

Shepard’s work said that within this futility, one could make a lot of noise, could leave a lot of claw-marks on the walls. A long, sustained career becomes a text in itself, and his life was a stunning progression from noise into a stillness, a long arc of forgiveness without absolution. Shepard’s late works were still relentless and bloody, but he aged into a taciturn elder statesman, someone who had lived enormously, who had filled up every corner of every room available.

A long, sustained career becomes a text in itself, and his life was a stunning progression from noise into a stillness, a long arc of forgiveness without absolution.

It’s dangerous to link one’s identity and the things one loves to human legends, but Shepard’s life, as much as his work, offers an exploded view of humanity, an argument against a world that asks us to make ourselves smaller and to shrink from hard truths. As it did when I first read his plays, his writing offers a route by which to expand into the horrors and rewards of living, a bloody and capacious permission for both rage and forgiveness. Both dads and gods are untrustworthy, worth breaking with and casting oneself far away from, growing up into languages that move beyond their imitation. But, as Shepard’s work and life show, these ghosts still stalk the landscape after we leave them behind. To confront them is to remind ourselves how we got where we are, and what we dreamed of being when we first looked to larger figures — to seek imaginary dads, to learn how to begin to speak ourselves into existence.