Books & Culture

What ‘Twin Peaks’ Can Teach Us About Writing—And Experiencing—Trauma

The show is a master class in portraying destabilizing experiences

When the first episode of Twin Peaks aired in 1990, I was captivated. In my early teenage years, I wasn’t quite sure what I was looking at, but like the fearless protagonist FBI Agent Dale Cooper mused to his voice recorder (and by extension, “Diane”), I was willing to go along on this journey to “a place both wonderful and strange.”

Earlier this summer, I revisited the original series before the long-awaited third series premiered. Watching Twin Peaks, a show that begins with the discovery of a Laura Palmer’s plastic-wrapped body, was a vastly different experience as an adult. By this time, two young women I knew in high school were murdered by men. I had lived through threats of violence and the trauma of living in a homeless shelter (and sometimes on the street). I had met countless young women marked by the trauma of abuse. Laura Palmer could have been a friend. She could have been me.

Laura Palmer could have been a friend. She could have been me.

Re-watching Twin Peaks meant revisiting the horror of abuse and murder, horrors that seemed far away in my youth, but that as an adult I felt deep in my bones. It was often an uneasy feeling to watch scenes that evoked these memories and feelings, but as a writer, I was interested in how Twin Peaks could achieve this effect through the structures underpinning its approach to storytelling. Here are the lessons I’ve learned from Twin Peaks about how to write trauma in a way that feels as visceral, surreal, and challenging as living with it.

Subvert Expectations

The original series was a police procedural couched in soap opera tropes. Agent Cooper arrives in Twin Peaks and teams up with the local sheriff to unravel the mystery of Laura Palmer’s murder. Each early episode ends in a cliffhanger and scenes are sometimes played against a fictional soap opera “Invitation to Love” — a drama preferred by locals — to highlight the mirroring that unfolds throughout the story of a small town plagued by dark secrets.

But if Twin Peaks is an amalgamation of these typical television story structures, it is also a subversion of them. Director and writer David Lynch, along with co-creator Mark Frost, poked at traditional by-the-numbers story structures. The love stories found in a conventional soap operas usually end in grand weddings scenes and, eventually, a new baby added to the cast. In a typical crime mystery, the audience would expect concrete answers to a central question: Who is the killer?

Expanding the Twin Peaks Universe

Lynch and Frost lulled viewers into specific sets of expectations, many of which they had no intention of delivering. The love triangle between Ed, Nadine, and Norma is left unresolved in the original series, while other romantic threads are left hanging indefinitely. The big question that kept viewers watching week after week during the original series run — Who killed Laura Palmer? — was only answered when network executives forced the show to identify the killer in the second season. Lynch decided to walk, only to return for the season two finale to highlight the many more important questions that existed beyond the perceived central mystery.

We could say that Agent Cooper follows a familiar story, reminiscent of epic poetry, including his visits to the “red room.” In many ways, he is our mythic hero journeying to the underworld. But Lynch teases out the hero’s return, and we can’t be sure he is triumphant. As a writer, what I find useful here is the toying with formality to surprise and upend our notions of what’s to come. I can adopt the fairy tale structure without entirely submitting to conventions; the heroine of my story might not live happily ever after. I’ve borrowed from missed connection advertisements to tell a story of loneliness, the label on a bottle of body wash to convey my unclean memories — to create something new and unexpected. In this sense, Twin Peaks’ storytelling shares similarities with “hermit crab” essays, braided essays, and other experimental forms that provide structures we can upend, just as the the foundation I knew became unsettled.

Don’t Be Bound by Linearity

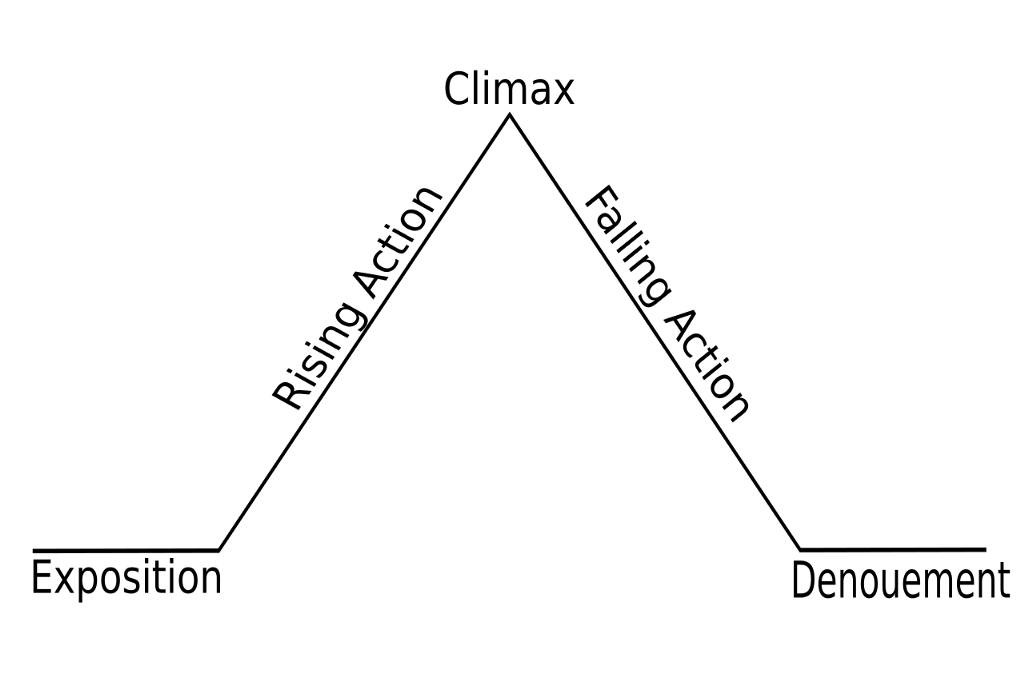

Most of us are familiar with the traditional plot structure found in Freytag’s pyramid. Stories begin with exposition, the action rises, we reach a climax, the action falls; and when we reach the dénouement, our anxieties are soothed. In the world of Twin Peaks our anxieties are rarely relieved. The rising action of one storyline, such as the identity of Laura’s murderer, appears to climax when “Bob” is revealed as having inhabited Leland’s (Laura’s father) body, but what “Bob” is remains a mystery. Just as we think we’ve reached the dénouement, the story shifts wildly during the second season finale, which takes place almost entirely within the “red room,” an extra-dimensional waiting area connecting good and evil meeting places.

Lynch and Frost became more structurally ambitious throughout the show’s recently aired third season: Twin Peaks: The Return. Chronological storytelling is shunned in favor of storytelling that spirals outward and inward at irregular beats, much like Agent Cooper trapped inside the mysterious glass box, shifting toward, and then away from, the viewer. In one episode, Bobby finds an item left by his father, but several episodes later, and at least a day later as the story proceeds, he appears in the Double R Diner and says he’s found the items that day. Lines are repeated and entire scenes are replayed as if time is looping. Or, perhaps we are hearing echoes from alternate timelines. “Is it future, or is it past?” is a repeating question, and a nod to the viewer. The answer: perhaps it is both.

Much of this aversion to linear storytelling stems from Lynch’s sense of “dream logic.” In the original series, Agent Cooper allows his dreams to lead him closer to the identity of Laura’s murderer. His dreams are treated as seriously as physical evidence; the line between the physical and dream world is intentionally blurred. Dreams, and the irregular structural logic behind them, are viewed as something not outside ourselves, rather, as an essential part of being, and therefore, an essential part of the Twin Peaks storytelling structure.

This unusual approach to storytelling spoke to me because it is the way I visualize my own story. My memories of homelessness often appear as dream-like, disconnected scenes without a clear narrative arc: a man threatening my life in the dead of night, a pregnant girl begging strangers for a place to sleep, the elderly man at the shelter who always saved a serving of butterscotch pudding for me. I often have difficulty pinning down exact dates, and memories of specific threats sound repetitious. Stories like Twin Peaks help me trust that I can lay out the pieces, collage-style, and arrange them in a way that makes sense to me while being honest about my experiences with readers. As writers, we might be familiar with narratives that jump around in time, but the reader or viewer is typically made aware of these shifts. The original series gave ample cues, but The Return was far less willing to take the viewer by the hand and, instead, trusted the audience to make sense of it all, as we might trust our own readers to do the same.

Vary Perspective

Before I had known death up close, I was repulsed by television shows that exploited the violence perpetrated against women for ratings: the CSIs, the Law & Orders. The victims in these stories seemed to function more like plot devices than fully formed characters we could imagine as people existing in the real world. When the original series aired, I wondered if Twin Peaks would follow the same path.

But Laura was always at the heart of the story. Even in death, she speaks from the beyond, through the “red room” scenes, the recordings she made for Dr. Jacoby, and her diary. Yet, as the series progressed, we began to question perspectives. At one point during a Twin Peaks: The Return dream sequence, we are asked, if we live inside our dreams, then “who is the dreamer?” Or: Who is telling the story? The series tends to turn the camera back to the viewers, prompting the question: What is the viewer’s place in the narrative? If Twin Peaks is also the story of how an entire town could be implicit in a girl’s abuse, then this shift in perspective is warranted.

As a writer, this view opens the possibility of adopting the perspective of someone outside myself to approach my own story. I might attempt to show a scene from that pregnant girl’s perspective, or the elderly man who showed me small acts of kindness in my darkest days. I’ve also found it helpful to experiment with second person point-of-view to close the distance between the reader and the events in a nonfiction narrative, particularly when the real life scenes I write about seem stranger than fiction. Perhaps an incident where I was cornered in a parking lot one evening seems cliche when written from an outsider’s perspective, yet, even as I often experienced the feeling of looking at myself from afar in times of danger, we can find ways to bring readers into that scene, and we might more often ask ourselves to consider the reader’s place in a story.

Resolution Is Not a Guarantee

The framework at the heart of Twin Peaks resists conventions at every turn, and this point is most evident in the series’ “ending” (if we can call it that), a point of contention I expect we will debate for years to come. Could Agent Cooper change the course of time and save Laura, or is this impossible, foolhardy optimism with dire consequences? Leaving the conclusion open to interpretation feels natural to the story’s internal logic, and further proves that Lynch and Frost have faith in the audience. As a writer, I admire this candid choice. Is there an ending to our stories? Can my own ending exist, or will I forever be haunted by my past as it echoes through my writing? Time and time again, my stories veer into darkness and resist clean endings, even when it is not my aim.

Viewers might find the disjointed nature of Twin Peaks difficult to parse, but the show’s messy, unpredictable narrative is closer to the truth of human experience if we are to weigh our internal, abstract lives as heavily as our flesh-and-blood veneers. To fully develop characters, and give them resonance within a narrative, the psychological life of those characters must ring true. Like the multiple planes of time and existence found in Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life, we live multiple lives devoid of orderly resolution.

Viewers might find the disjointed nature of Twin Peaks difficult to parse, but the show’s messy, unpredictable narrative is closer to the truth of human experience.

I’m as tempted to unlock the mysteries of Twin Peaks as much as any fan, and I cling to a few theories closer than others. This is a show that resists clear mapping from one episode (or “part”) to the next and rewards repeat viewings like a complicated novel that begs to be re-read. Watching The Return, I couldn’t help but think of Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves, and books built on the “multiple pathway” experimentation found in anti-novels (or “counter-novels”) like Julio Cortazar’s Rayuela (or, Hopscotch), and in the same vein, Ana Castillo’s The Mixquiahuala Letters.

Rather than a puzzle to be solved, Twin Peaks opts for mood; to do otherwise would be inconsistent with the open-ended nature of trauma. We are set adrift between oceans of “what-ifs” resting in multiple times and dimensions, just as I wonder what if I had made different choices or circumstances had changed. The final episode introduces a realm that feels both familiar and remote, populated by recognizable faces known by other names. A house is no longer the home we knew. When I write about sleeping in a bus station, I know the danger intimately, but at the same time, it feels as though it happened to another person in a time and space outside everything I know today. Home became an empty silhouette, its meaning forever changed.

Laura is continually reborn, never fully fading from the narrative, but we are left to question if the horrors she endured will perpetually cycle. Our hero takes Laura by the hand and attempts to lead her out of a darkness that may be, tragically, inescapable. If “Bob” is vanquished, there is still “Judy,” evil by another name, just as my own experience with homelessness led from one danger to the next. Perhaps Agent Cooper is merely the fabled knight wished for by those who know him as pure fantasy, a hero who inevitably loses his grip and is left searching for resolution.

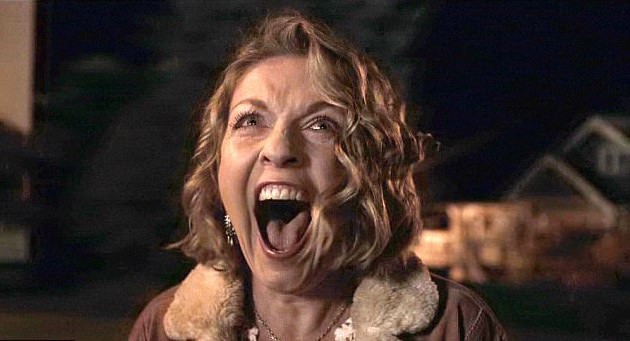

Twin Peaks concludes on Laura’s sudden, terrifying scream, as though she feels the echo of trauma that cannot be erased from the narrative no matter how the lens shifts — an end note I identify with. Pain cannot be extinguished in favor of closure. Although the stories I’ve grown up with dole out justice and right wrongs, this is not my story, nor the stories I write. I feel a responsibility to resist the type of writing that confines trauma to easy endings. Like Laura’s silenced voice whispering into Agent Cooper’s ear as the credits roll, the telling is a struggle, but we must continue to find ways to make our voices heard.