Books & Culture

What We Remember: One Small Act Replaces the Rest

This is a follow-up to the author’s New York Times piece, “My Mother is Not a Bird.”

My grandma has her favorite stories.

Over lemon meringue pie she’d say, “The night I met my Julie, I went to a dance at the synagogue. When I came home, I said, ‘Papa, I just met the man that I’m going to marry.’ ‘What?’ he asked. ‘He proposed already?’ And I said, ‘No, he just doesn’t know it yet.’”

She speaks in loops, telling the same stories over and over.

“When David was little, he asked for a sandwich. I asked, ‘Why don’t you make your own sandwich?’ And he said, ‘Tastes better when you make it.’”

The stories were about family, and often food.

“When your mother was pregnant, she got this huge chocolate sundae, three scoops! I asked her, ‘Can I have some? Just a little bit?’ And she said, ‘Get your own!’” To that story my mother always answered, “I was pregnant. I was already sharing!”

These memories became touchstones. She told them enough times that it didn’t matter if they happened before or after I was born, I felt like I was there.

But at ninety-three years old, her loops are getting shorter, her stories fewer.

She no longer says, “My mother was a teddy bear who fed the whole neighborhood. Everybody loved her food.” Or: “My father was the kindest man I ever met. He owned the general store. When the boys came home from the war they said hello to him before they went home to their families!”

These stories have subsided. Now she asks just one question.

“Where’s Mario?”

Mario is my twenty-year old brother-in-law. She’s met him maybe three times. Yet that last time has stuck with her so meaningfully that she talks about it every day.

One act of kindness rises above ninety years’ worth of memories.

Four years ago, Mario sat on a couch and talked to her for about two hours. The subject of the conversation doesn’t matter. It wasn’t something he said. It was that he said something, for two — sometimes she likes to say three — hours. “Who else would sit with this old so-and-so for three hours?” she asks. “That’s my kind of guy!”

One act of kindness rises above ninety years’ worth of memories.

And I’m glad. Too easily sad, painful memories can supplant the rest. Three years ago her children, David and Linda, both died within a week of each other — one expectedly, the other not. Until recently I didn’t realize that she copes with this by forgetting.

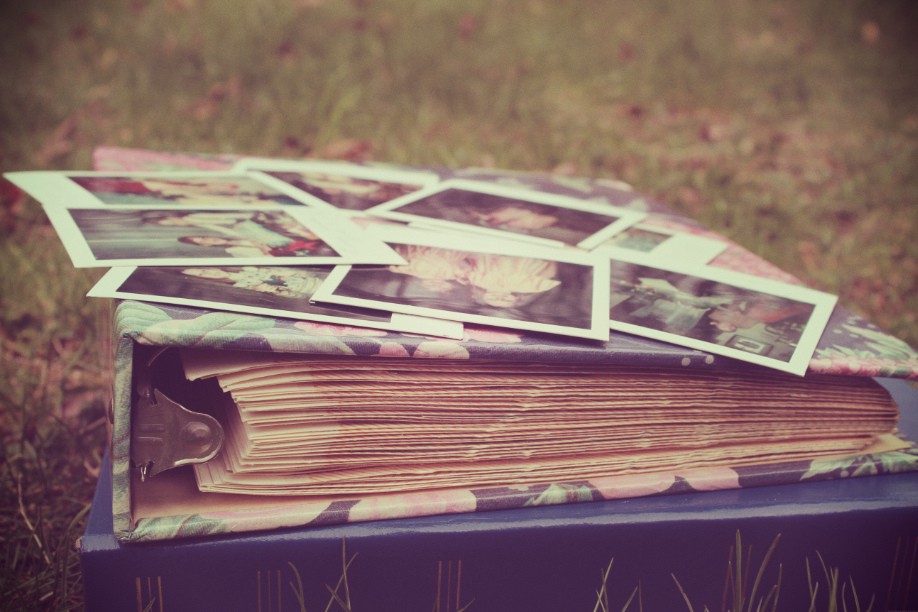

We were looking at old family photos and she froze. “Is David alive?”

The fact that she had to ask triggered a panic in her eyes. On some level she had to know. On another, she didn’t.

“No, Grandma, he died.”

“How did he die?”

“He had a heart attack.”

She barely absorbed this information before she turned to me again. “What about Linda? Is Linda alive?”

“No. She had cancer.”

“How could I forget?” She searched my eyes. “How could I forget that my own children died?”

She answered herself. “I must have made myself forget because it was too painful.”

Her ability to alter painful memories is something researchers have been trying to do for PTSD patients for years. According to the American Psychological Association, researchers have experimented with lasers, xenon gas, drugs, and exercise to test whether bad memories can be altered or erased.

“How could I forget?” She searched my eyes. “How could I forget that my own children died?”

By focusing on a positive memory, my grandma may have found her own way of fighting off depression. In fact, one study published in Nature, featuring the work of neuroscientist Susumu Tonegawa and his team at MIT, seemed to show that positive memories could alleviate depression in mice. While my grandmother isn’t a mouse, her ability to focus on that one special moment gives her enough joy to forget the pain of being a mother who outlived both her children.

Watching her mind change has been difficult. When I was little she’d take me to museums and the Seaport. She’d cook tuna croquets and spaghetti. She’s someone who started college in her sixties and learned to drive in her seventies. Living with my parents and me, she’d wake up extra early every morning to make me breakfast, even though, cranky and ungrateful, I never ate the oatmeal or toasted bagel.

My grandma isn’t easy to please either. This is the same woman I once found gripping her crossword in a completely unlit room. When I asked her, “Should I turn on a light?” She answered, unironically, like the Jewish mothers in the joke, “No, I’ll just sit in the dark.”

Knowing her intransigence makes the power of Mario’s kindness even more of a triumph.

She’s always had a way of making singular requests like, “Will you make me just one sugar cookie?” But you know what? After she asked, I baked a whole platter of sugar cookies, and even cut them into circles using the lip of a glass like she said her mother used to do. Her grin when I brought out that mountain of cinnamon-sugar dusted cookies made it all worth it.

Although she may not remember that now, it’s the joy of that moment that counts — for both of us. In her book The How of Happiness, psychology professor Sonja Lyubomirsky describes how performing small acts of kindness can benefit someone’s mood, self-perception, and overall health. Perhaps that’s why for years my grandmother shared her own act of kindness: “When I was eight years old, I wanted to help my parents have extra money for the holidays. So I sold greeting cards door-to-door. And I sold every last one!”

Kindness cuts through the rest. And it’s a reminder for us all to reach out. Write that sweet note. Make that loving phone call. Because you never know what will stick.