Books & Culture

What Wonder Woman Meant to Her Earliest Fans

The midcentury comics’ version of womanhood might not satisfy modern-day feminists

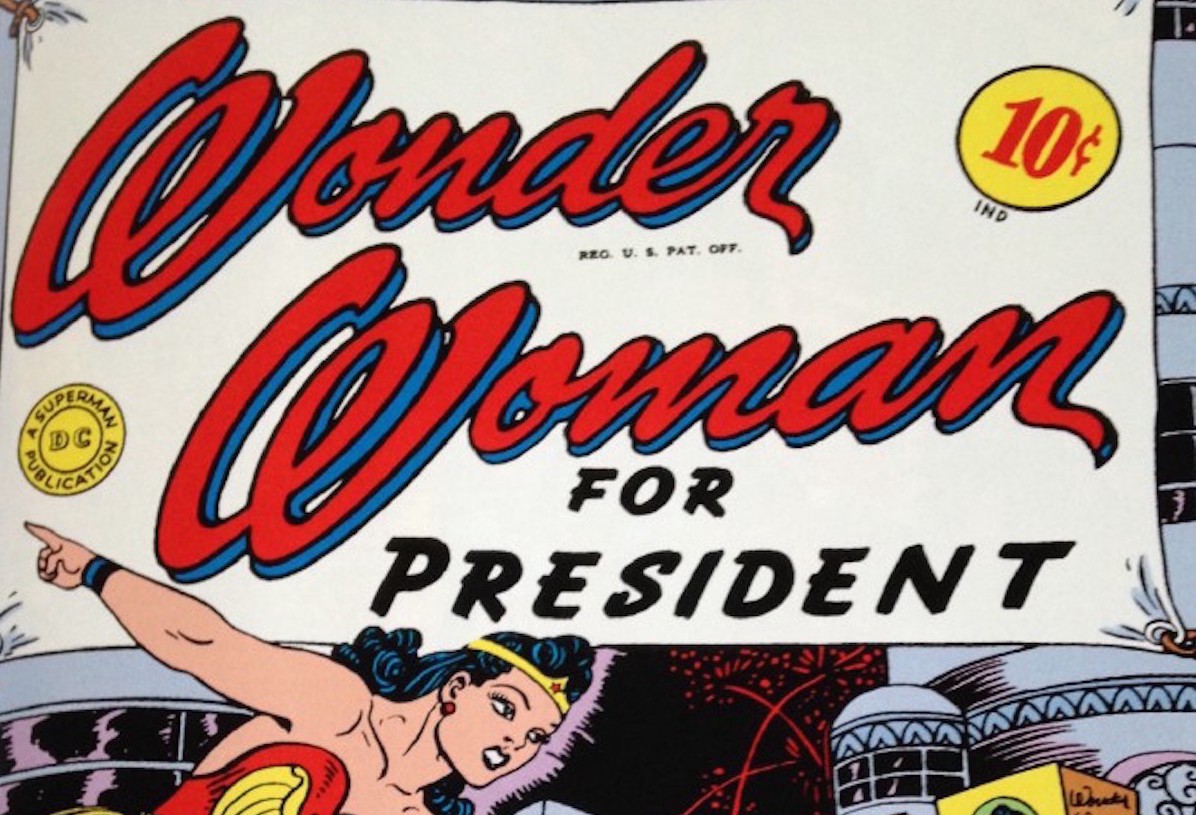

In Wonder Woman #7, published in the winter of 1943, Diana and her mother stare into their Magic Sphere on Paradise Island and see that in the future, a woman will become president. (Before praising Wonder Woman’s creator, Charles Marston Moulton, for his progressiveness, note that he sets this victory in the year 3004 A.D.) The opening blurb states that it will be “Wonder Woman herself, that gorgeous, stupendous personification of all that is glorious in American Womanhood” who will be president. The superhero’s alter ego Diana Prince runs on behalf of the “Woman’s Party” against her very own Steve Trevor. After watching herself take the oath of office in the Sphere, Diana turns to her mother and says, “Oh Mother, he didn’t beat me after all — I almost wish he had. Poor Steve!”

Contrast this sentiment with the feminist (particularly white feminist) embracing of the new Wonder Woman franchise. While comparative essays exist discussing dueling origin stories in the comics and movie and the sanitized sexuality of the film, the context and substance of these early comics deserve critical examination. What did American womanhood mean to a 1943 audience?

After watching herself take the oath of office in the Sphere, Diana turns to her mother and says, “Oh Mother, he didn’t beat me after all — I almost wish he had. Poor Steve!”

Wonder Woman debuted in All-Star Comics #8 in 1942, with her origin story marking her early years with her Amazon sisters (including jousting atop kangaroos) and the fateful crash-landing of Steve Trevor on Paradise Island. Diana opts to leave the island to aid the world of men, bringing with her a magic lasso, mind-controlled radio, and invisible jet. Besides these gifts, she wears her characteristic costume and her bracelets, which repel bullets but also act as kryptonite if chains are attached to them by men. Charles Moulton Marston’s explanation of the constant chaining up of Diana has been described, on one hand, as a nod to the struggles of the suffragettes. On the other hand, Marston once justified the chains to his editor by saying that “women enjoy submission.”

Wonder Woman, of course, wasn’t written as a primary text for cultural sensitivity and enlightenment, but for entertainment. One memorable episode matches foe Paula von Gunther against Diana Prince in a scheme to cease accessible milk supply for the youth of America in order to cripple the armies twenty years down the line. One has to appreciate the ridiculous long-sightedness of a villain like that, as well as the obvious schilling in the comic for the American dairy industry.

Early Wonder Woman comics matched the heroine, her bandleader-sidekick Etta Candy, and love interest Steve Trevor against two types of bad guys: WWII-era Axis spies or Greek gods from outer space. Both of these types of adventures veer into uncharted territories of non-sequiturs. For instance, in Comic Cavalcade #1 (Winter 1943), while attempting to rescue a boy from a Nazi submarine, Wonder Woman stumbles upon Hawthorne’s House of Seven Gables, which becomes key to her victory. And then there’s Sensation Comics #13, where Wonder Woman, rumored dead, reveals herself at a co-ed bowling championship (and defeats Nazis).

Pop Cultural Propaganda

Zany plot twists aside, the widespread nature of comic books meant their cultural impact went beyond entertainment. These comics marked the golden era of comic books, at least in terms of sales. Scholars Ames and Kunzle note that 18,000,000 comic books were sold monthly, making up a total of a third of all magazine sales in 1943. It’s not surprising to find overwrought plotlines in 1940s-era comics. Duncan, Smith, and Levitz note in The Power of Comics that early comic books mixed the format of comic strips with the drama of the “hero pulps,” like The Shadow and Doc Savage.

Alongside the superhero drama in early Wonder Woman stood the real-world antipathy of the Axis Powers. This comic’s portrayal of patriotism matched many of the concerted national efforts geared toward women and children at the time, who happened to be Moulton’s major audience. Rarely did American propaganda posters put out by the army show explicit, photographic realism of the battlefield. Instead, images like Rosie the Riveter became popular. Likewise, many Wonder Woman comics at the height of U.S. involvement in the war featured a plea to buy U.S. stamps and bonds. In one episode, Diana Prince wrestles an opponent for war bonds.

Wonder Woman comics at the height of U.S. involvement in the war featured a plea to buy U.S. stamps and bonds. In one episode, Diana Prince wrestles an opponent for war bonds.

Marston’s tagline, which asserted that Wonder Woman represented “the ideal of glorious modern American womanhood” appeared frequently in the early comics. As alter-ego Diana Prince worked at Army Intelligence Headquarters, she had access to military documents and, as Wonder Woman, she often worked in partnership with the American government to complete missions. In Sensation Comics #20, for instance, Diana Prince goes undercover in the WAC, the Woman’s Army Corps.

Public perception and popular media depiction of the WAC forces were mixed. Leisa Meyer writes in Creating GI Jane: Sexuality and Power in the Women’s Army Corps During World War II that cartoons of the era depicted the possibility of subversion of men’s position as head of the household “with drawings that included a man sitting at home knitting a sweater for his WAC wife, as well as a frail-looking bespectacled husband wearing an apron and wielding a broom while asking his Army wife at the door if she had his monthly dependency allowance.” In contrast, Marston’s depictions of women working in munitions factories and digging trenches certainly illustrate the power of women.

The reality of WAC life was more complex than either of these diametric views. On one hand, Meyer writes, WAC units served in combat areas overseas in noncombat roles. In making this “noncombat” distinction, the Army could place American WACs to Europe to serve, but also “could preserve the roles of some men as ‘protectors/defenders’” if they remained at home. Still, even though WACs served noncombatant roles, they experienced many of the dangers of all Army service personnel at the time, such as air raids and open fire.

White Saviors, White Saved

In Marston’s comics, secret Axis agents are constantly in Diana Prince’s business, usually putting poor Steve Trevor in peril. Unlike modern superheroes, the majority of Diana’s foes have no superpowers of their own. In most plots, the weapons of war are loose lips, lost plans, and espionage. Many storylines include female victims and female criminals who are usually redeemed by the end of the story. Diana’s most common foe in the early comics is the Baroness Paula von Gunther, whose mob of female slaves often tricks Diana into captivity. Later in the series, Paula is redeemed; it turns out that her service to the Nazi cause was due to her daughter’s imprisonment. Once little Gerta is freed, Paula joins the women of Paradise Island and the Amazons. Marston writes that many of Paula’s female slaves join her, but, as if in some kind of BDSM fantasy, many of them still prefer to be chained up a good deal of the time. Later, the blonde and bumptious Priscilla Rich, “the glamourousest deb in America,” has a similar redemptive arc.

However, redemption usually only came for white villains. The Japanese Princess Maru reoccurs frequently as a non-repentant foe, and Yasmini, an Egyptian princess, dies rather than reforming. No matter the gender of the opponent, non-Western cultures in Wonder Woman often match the sensitivity of Mickey Rooney’s role in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Racist lingo, like “Nip,” jars the modern reader during any battle against the Japanese. Marston was far from the only comic or cartoon purveyor to use such language during the time period. The exoticism of the villains is both exploitative and audience-driven. After all, as comic books began to replace pulp magazines, they offered a cheap version of escape. Wonder Woman not only served a patriotic cause with its red, white, and blue spangles, but served to feed into the idea of American exceptionalism.

Wonder Woman not only served a patriotic cause with its red, white, and blue spangles, but served to feed into the idea of American exceptionalism.

The designation of “true American” in Marston’s eyes seems further limited by color. Just as galling as the portrayals of Asian characters is the (rare) portrayal of African Americans in Marston’s early comics. In Wonder Woman, roles for black characters are limited to those of busboy, porter, and maid. In a time of war, the lack of inclusion of black service members comes across as a particularly jarring absence. As described in Meyer’s Creating GI Jane, black women made up 10% of the original WAC forces. In Wonder Woman’s WAC adventures, however, only white service members are pictured, consistent with the segregationist policies of the time period. With so many black service members, both male and female, Meyer notes that black press at the time advocated for a “Double V” strategy — victory against foes abroad and against racist policies on the home front. That effort would fail to be realized, even in comic books. Even the Amazons of Paradise Island appear white.

The new movie’s diverse cast of Amazons is one step in the right direction, though a modest one, and with a female director and a strong box office return, Wonder Woman 2 is a certainty, as is the 2019 scheduled release of Brie Larson as Captain Marvel. Scan the rest of the upcoming releases in the superhero genre, however, and things look less female-led indeed.

In Wonder Woman, roles for black characters are limited to those of busboy, porter, and maid. In a time of war, the lack of inclusion of black service members comes across as a particularly jarring absence.

How much can one ask of a single superhero? Wonder Woman carries the nostalgia and admiration of millions in her various re-imaginings, but she also drags cultural baggage with her. Hope Nicholson points out in her book The Spectacular Sisterhood of Superheroes that Wonder Woman isn’t anywhere near the only female superhero, but she was one of the earliest and remains one of the most enduring. Nicholson writes, “Diana has the added pressure to be everything. And as a result she becomes nothing.”

In the scene in which Wonder Woman takes the oath of office in 3004 on behalf of the “Woman’s Party,” Marston never writes that Diana Prince is the first woman president of the United States. Comic characters like the 2015 reboot of Ms. Marvel and the forthcoming Ta-Nehesi Coates-led Storm series offer new superhero possibilities to readers. Hopefully, young people will dig into the genre of comic books beyond Diana Prince to the wide selection of characters that explore, with complexity and tenacity, the new meanings of American womanhood.