Interviews

When the Family Business Is Pot Brownies

"Home Baked," Alia Volz's memoir of her mother, is also a love letter to '70s and '80s San Francisco

Alia Volz’s mother, Meridy, moved from the Midwest to San Francisco in 1975. An artist with an affinity for magic, Mer got by doing illustration work and occasionally peddling tarot readings on a rug on Fisherman’s Wharf. That is, until July 4, 1976, when Mer’s marijuana brownie selling friend, the Rainbow Lady, called her and said: “I’d like you to take over the business.”

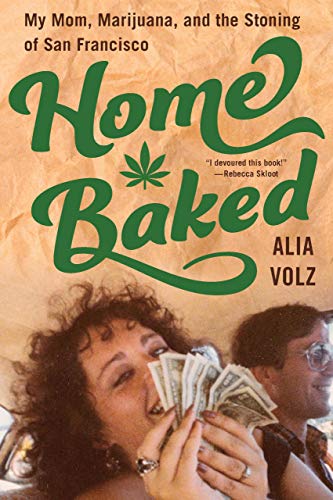

In Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco, Volz chronicles Mer’s time running what would become her super successful brownie business, Sticky Fingers. Volz details how Mer, with the help of Volz’s father Doug, and a spirited cast of characters grew the small operation into a San Francisco phenomenon which sold 10,000 brownies a month. Weaving together oral history, archival research, and her own personal memories, Volz uncovers the connections Sticky Fingers had to a wide range of historical events from the assassination of Harvey Milk to the Jonestown Massacre and the AIDS crisis. Through her examination of Sticky Fingers and the circles it operated in, Volz masterfully documents the history of San Francisco’s LGBTQ+ and artist community in the 1970s and ’80s.

As the COVID-19 pandemic began to sweep through America, Volz and I—both sheltered in place on opposite coasts—exchanged notes wishing each other and our cities well. We then went on to discuss growing up in an alternative family, recording people’s stories, her mother’s contributions to the seismic shift in our country’s views of cannabis and the reverberations the Sticky Fingers story still has today.

Elizabeth Lothian: Your mother “inherited” the brownie business on America’s bicentennial. The views of our country at the time were very different as compared to today—beliefs and laws about pot were draconian and the role of women in society was greatly limited. When you started writing Home Baked did you recognize the many ways in which your mother, as a business owner and a woman, was a pioneer?

Alia Volz: My mom doesn’t view herself as a pioneer. Isn’t that odd? If you ask her directly, she’ll stammer around the answer. She was just following her gut, her hippie oracles, and her conscience. Of course, I knew my mom was exceptional—and that she took unusual risks. But I didn’t feel the weight of her contributions until I’d spent years studying the history of medical marijuana and the evolution of U.S. drug policy. It was a nice surprise!

I knew my mom was exceptional. But I didn’t feel the weight of her contributions until I’d spent years studying the history of medical marijuana.

EL: That’s so interesting that it took studying the history of medical marijuana and our country’s drug policies for you to appreciate your mother’s contributions.

AV: One thing about growing up in an alternative family is that it feels normal. Breaking laws was normal. Baking and wrapping thousands of pot brownies together was normal. Lounging around with my mom and her customers was normal. The broader social and political implications of my mom’s work only became clear through research.

EL: Speaking of research, you note in prologue that you began compiling the history of Sticky Fingers over a decade ago by recording your mother’s best stories. At first this was just for yourself but then as she told more stories, your curiosity about the vastness of her contribution to not only cannabis history but to the greater societal movements of San Francisco and America at large grew. Can you walk me through how you expanded your research from there?

AV: It was organic. There were questions my mom couldn’t answer. She’d say, “You should ask Barb about this.” So, I went to my godmother Barb, who brought more people into the project. My interview pool expanded much like the brownie business back in the day—through word of mouth. I had to hunt down a few folks, but most of the connections flowed naturally. I tried to keep it that way. Then I used what emerged in interviews to guide my archival research.

Inevitably, my sources contradicted each other. Sometimes they contradicted historical record. I found these misalignments fascinating and tried to weave them into the book. The stories we tell ourselves about our past say a lot about our self-image, state of mind, desires, etc. What we forget defines us as much as what we remember.

EL: You weave in the spirit of San Francisco in the time of Sticky Fingers in such a natural and nuanced manner. Larger than a backdrop for telling the story of the business, it becomes the heartbeat. Do you think that Sticky Fingers would have been able to flourish in the ways in which it did if it had been started in a different city?

It gave us a population of dreamers—which, when you think about it, is an ideal market for marijuana.

AV: An old saying has it that, “The country tipped sideways, and all the loose screws rolled to California.” San Francisco was built on waves of mass migration—usually of people chasing an illusion. Think of the Gold Rush, the Summer of Love, the dot-com boom. In the ‘70s, the Gay Liberation movement drew folks from all over the world looking for a safe place to live out of the closet. The fantasies were usually overblown, but once people came here, they stayed and did other things. It gave us a population of dreamers—which, when you think about it, is an ideal market for marijuana.

Sticky Fingers Brownies was a creature of the ‘70s. Consider this: some people were buying illegal pot brownies to use on the job. It’s hard to imagine anyone doing that in San Francisco today, even though it’s legal now. The cost of living is too high to risk losing your job. Back in the day, work took a backseat to lifestyle and creativity.

San Francisco is also a physically small city. The population in the ‘70s was only about 700,000, and I think that made word of mouth particularly effective. Later, when the AIDS crisis hit, the intricate social networks helped us face the pandemic in innovative ways.

EL: Your mother is an artist, as is your father who comes to join the Sticky Fingers empire, and the majority of people in the Sticky Fingers world. Through telling their stories you end up documenting the history of the artist community in San Francisco in a personal and greatly detailed way. Was it important to you to archive the history of this community—especially as it seems to be an ever dwindling one in San Francisco?

AV: Very much so. This project is driven by oral history. I would ask former customers about their relationship to Sticky Fingers Brownies and end up hearing about amazing art scenes and culture pockets, many of which were influential but not well-documented. Stories carry a weight of responsibility. I wanted to save it all.

Some rabbit holes consumed me. There were months when I did nothing but interview buskers who’d worked Fisherman’s Wharf during the golden age of street performance; they called it the New Vaudeville. I fell in love with those stories and could’ve written an entire book on that alone. I had to restrain myself to make room for the punks, psychics, disco queens, genderfuck theater radicals, and so forth. So many obsessions! In the final draft, the buskers of Fisherman’s Wharf are condensed into a few pages. The hardest part was committing to one through line and cutting the rest.

Today, we’re facing a pandemic that specifically endangers elders. Now is a good time to ask parents, grandparents, and elderly friends about the stories they carry.

When people pass away, history dies with them. Today, we’re facing a pandemic that specifically endangers elders. Now is a good time to ask parents, grandparents, and elderly friends about the stories they carry. If you can record, even better. People are full of surprises.

EL: You make a great and especially timely point about the history people carry with them through their stories. Many significant moments in American history are intrinsically connected to the Sticky Fingers world—from the “gaycott” against Florida citrus to the Jonestown massacre and the assassination of Harvey Milk. I felt like I learned so much more about these moments through your writing than I had in history and social studies courses! When you began writing Home Baked did you know the Sticky Fingers story would connect to these moments?

AV: The ‘70s in San Francisco were frothy and dynamic; the ‘80s were intense. I knew the material would be rewarding. But I didn’t grasp from the outset how intricately the story of Sticky Fingers was interwoven with those historic moments.

EL: So, you began to discover more of their connections as you wrote and researched?

AV: Again, oral history guided the narrative. An interviewee would tip me off to a connection and I’d hit the books and newspaper archives to flesh it out. I kept having to pry myself out of tangents. My rule became that I could only write a given scene if an interviewee gave me a firsthand account, so I’d have something fresh to say about it. If there wasn’t a clear link to Sticky Fingers, I let it go, no matter how intriguing. Fortunately, the Sticky Fingers crowd had their fingers in a lot of pies.

For example, I didn’t find out until the penultimate edit that Cleve Jones had been an occasional customer.

EL: Wow! I’m so glad you were led to him. Reading about Jones, his contributions to celebrating the lives of those who died from AIDS (often without proper funerals) was incredibly moving.

AV: I knew him as a key figure in LGBTQ+ history but wasn’t planning to involve him. One interview led to another, and suddenly I was having a three-hour conversation with Harvey Milk’s protégé and the force of nature behind the AIDS Quilt. Cleve shared marvelous stories about Sticky Fingers and the greater community—cracking open historically vital scenes. I almost missed him!

EL: The AIDS crisis comes to loom large in the narrative as the Sticky Fingers story progresses. The compassion your mother showed during this time, as she brought brownies to those who were suffering in an effort to alleviate some of their symptoms, while most of the country sat back and did nothing, was heartrending to read. At the time was the magnitude of the crisis clear to you.

AIDS was very real to me. I had nightmares about loved ones getting sick, and some of those dreams came true.

AV: An ACT UP activist named Vito Russo said, “Living with AIDS is like living through a war which is happening only for those people who happen to be in the trenches.” Well, I was in the trenches as a child. AIDS was very real to me—and much more dramatic and serious than anything happening on the schoolyard. I had nightmares about loved ones getting sick, and some of those dreams came true. Keep in mind that, until 1996, there was no effective treatment. Diagnosis was a death sentence.

EL: Russo’s quote is haunting, both in retrospect and now viewed from the lense of our current pandemic. During the height of the AIDS crisis, when you were delivering brownies to those who were ill with your mother, did you know the great service she was doing or was it something that became clearer as you looked back while writing?

AV: I knew my mom’s role was positive. When she did home deliveries to folks who were too sick to go out, you could see the relief on their faces. A brownie wasn’t going to cure anyone, but it might get them through the day with less anguish.

What I didn’t grasp then was how profoundly the Reagan Administration abandoned the LGBTQ+ community. These beautiful young men were dying horrible deaths by the thousands, and the president refused to discuss it publicly for years—not until 20,000 people had died. Reagan’s press secretary mocked journalists for asking questions about a disease that affected “fairies.” I was scared as a kid; as an adult, I’ve become furious.

It was also through research that I came to see my mom as part of a seismic shift in our society’s relationship with cannabis. Today’s trend of state legalization grew directly from medical-marijuana activism during the AIDS crisis.

I started this book as a story about an eccentric family—just navel-gazing. Through a decade of research and writing, the story expanded beyond my family, beyond my hometown, beyond its era. You can feel the reverberations today.