Books & Culture

When the Ghosts Peel Our Eyes Closed: Reconsolidation: Or it’s the ghosts who will answer you by…

W

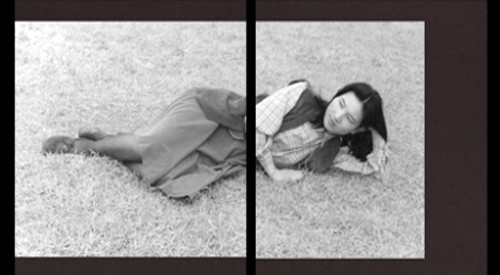

Janice Lee’s Reconsolidation: Or it’s the ghosts who will answer you drops the reader into the fissure created by unexpected loss. Writing a mere four months after the death of her mother, Lee recalibrates what we think we know about loss and memory. We, the still living, want to hold onto that which has gone, but with each act of remembering, we run the risk of reshaping, misremembering. Lee examines both rifts: the loss of the person, and the less obvious one, that of the slipperiness of recollection.

In a lesser writer, tackling this material without some distance could have gone awry, but Lee uses immediacy to good advantage. She writes, “I haven’t been able to escape her in my dreams,” something that began only with her mother’s passing. She then posits the idea that “dreams are closer to the real than one thinks,” that perhaps what comes to us in our sleep, because it is unfiltered, might have its own kind of honesty. She offers these dreams up for our examination, not as some message from beyond or even a call from her self-conscience, but rather as some alternate version of truth.

(T)here’s only one dimension that matters, the dimension we’re able to access when the ghosts peel our eyes closed and remind us of the past events we so viciously try to tuck away.

Instead of drawing attention to her grief, Lee has us share in her bewilderment. While describing the early morning phone call from the hospital, Lee shifts abruptly to the neurological aspects of memory accumulation.

Consolidation is the neurological process that stores memories after an experience. Reconsolidation occurs when a memory is reactivated and therefore destabilized. As previously consolidated memories are recalled, they enter a vulnerable state and are actively consolidated again.

We speak of memory as something like a palimpsest or an erasure. But what if it is a bubbling morass? This jelly-like state may well be where misremembering is born. Consider reconstituted foods: they are similar, but not the same. Or, as in some cases, the process makes them permanently altered, barely palatable.

Recalling a memory during these stages of inadequacy, repentance, sought-after impossibilities, recalling a memory under these conditions may be dangerous. The memory, a symbol for a strange form of affliction and permanence of love, may be changed forever.

It is only after this pause, that we learn that Lee’s mother has had an aneurism, is brain-dead, and being kept alive on respirators until the family can arrive. We are with Lee, sorting, knowing we are being watched.

It was the family that was on display, how we were taking it, whether we were crying, how we were dealing with the situation, their sympathy and pity pouring out of their eye sockets.

As Lee is, we are in the last moments we spent with a loved one, fantasizing that we might like a do-over, wanting that person to know one more fact about us or us about them. Consider the premise that death might be worse for the living.

I don’t know what the afterlife is like for others, but for me, it is the period after a life, after the life of that woman who brought me into this world.

Many memoirists urge the reader to know the writer’s loss by sharing what they recall feeling, wanting the reader to know what it was like to experience their specific loss. Lee, however, interrogates her own memories and dreams, trusting nothing. She assures us, “False memory is a normal phenomenon,” which is no assurance whatsoever.

A gaping hole I cannot understand:

Is this what trauma feels like?

Brevity and an objective stance serve the author’s purpose well. This lean and muscular text is best ingested in one shot, not unlike the way we experience pivotal events. An uninterrupted read allows for an accumulation of the quick changes from the author’s experience to critique of the machinations of memory and back again. This layering and interrupting, asserting and questioning, felt authentic to the experience of sorting out trauma. It is a piercing wail rather than a protracted weep.

I’m afraid one day I won’t be able to remember her face at all. Or even worse, the face I remember won’t be hers.