Books & Culture

Why Are We So Obsessed with Creepy Dolls?

In literature and beyond, the toys children adore show up to scare adults

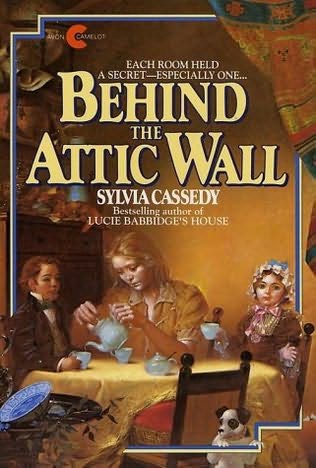

What do our favorite books from childhood say about us? I recently reread Sylvia Cassedy’s Behind the Attic Wall, which I loved obsessively as a pre-teen. I loved it all over again, but it did make me wonder: Why, among all my beloved books about babysitters and teen twins, was this creepy, unsettling novel the one that became my favorite? It’s a quirky choice, woefully underrated as middle grade readers go, lacking the cult following of the similarly weird A Wrinkle in Time, though I can’t for the life of me figure out why. This book is the whole package. Here we have Maggie, a misunderstood orphan (as in any kids’ book worth its salt — hi, Mary Lennox! Hey, Harry Potter!), who, in true fairy tale fashion, is sent to live with a pair of maiden aunts in a large, empty, potentially haunted house. There is a wryly funny uncle for comic effect. There are mean girls to rebel against. And of course, spooky living dolls squatting in a secret room in the attic. I mean, what’s not to love?

I didn’t quite understand, as a kid, what drew me to this book, but I loved the happy/sad feeling it gave me, the surreal sense that lingered after looking up from its pages. It was like the literary equivalent of spinning around too much, or spending 15 minutes hanging my head upside down off the couch. It allowed me, somehow, to see the world afresh.

Rereading the book for probably the twelfth time, I am struck by how tightly constructed it is, and how shot through with strands of the uncanny. I suppose no one should be surprised at Cassedy’s skillful craftsmanship; she attended the Writing Seminar program at Johns Hopkins, taught creative writing, and in her relatively short career wrote a manual on writing, among other things. Thus, on the first page, we know we are in an unsettling, unsettled world:

The man waiting at the station when she first stepped off the train was the tallest person she had ever seen. His round hat moved like a planet above the crowd, and the silver knob of his walking stick hovered just below it like a moon as he made his way toward her on the platform.

That first moment is disorienting, with that inhuman-seeming description of Uncle Morris. When Maggie first enters the house, which she is still convinced is the boarding school for girls it clearly used to be, she is startled by a ghostly figure who turns out to be her own reflection, which “hung fragilely within its frame.” Everything she sees is familiar and unfamiliar, definable and indefinable. Significantly, Maggie is 12, an age at which the world — oneself, even — is generally familiar and unfamiliar, definable and indefinable. It’s an age at which most girls don’t quite know themselves, and Maggie has no one to help her navigate it.

Right away we understand that Maggie is different from most girls. She is unpleasant and poorly-behaved (a welcome transgression from the virtuous heroine of many girls’ books, or so I felt circa 1990). The book’s obtuse adults don’t like her and for once it’s not really their fault. She’s genuinely unlikeable. The most sympathetic reader barely likes her, at least at first.

The book’s obtuse adults don’t like her and for once it’s not really their fault. She’s genuinely unlikeable. The most sympathetic reader barely likes her, at least at first.

As Maggie surveys the parlor, presided over by portraits of the original founders of the erstwhile Academy (remember them, they’ll be important later), she fixates on a china ballerina. Morris says, “Have you ever thought what that must be like?…I’m told it’s rather pleasant. Being a piece of china.” On a first read this seems a sign only of Morris’s eccentricity, a way to illustrate Maggie’s refusal to play along. But this exchange turns out to be oddly prophetic.

As Maggie explores the house, we are invited to recognize the uncanny nature of the place. Surveying the long empty hallway of closed doors, Maggie feels “a deep chill, cold as the breath of a passing ghost.” An empty chamber retains ghostly traces of a long-ago schoolroom. Soon she hears voices echoing throughout the empty house, and as the months pass, the voices begin to call her by name. She finally tracks the voices down through a secret passage in the attic and finds — what else? A couple of large, knee-high china dolls who have set up house in an IKEA-showroom-like arrangement of doll furniture.

When Maggie first sees the dolls’ lair, “everything had the air of being suddenly abandoned.” She searches for whoever has been playing with the dolls, but as it turns out, the dolls (though they don’t move their mouths or eyes), are in some impossible way alive, and have been the voices who have been talking to her. Deliciously, they refer to Maggie as “the one.” There it is, the key moment in any children’s novel — Harry Potter receiving his owl-mail, Meg Murry’s visit from Mrs. Whatsit, Charlie’s discovery of the last golden ticket — the revelation that this oddball child is actually special and important. That people have been waiting for her. It is, I suspect, the secret wish of every growing bookworm grub. Every child wants to feel chosen.

People have been waiting for her. It is, I suspect, the secret wish of every growing bookworm grub. Every child wants to feel chosen.

Significantly, the attic dolls aren’t scary. They comport themselves with starched propriety, asking normal, playing-house kind of things of Maggie. They would like help with pouring the tea at their tea party, and with taking their dog to the “garden” (an area of the attic wallpapered in roses). At first Maggie violently refuses, snapping at them, “I don’t play with dolls.” And it’s true, really — having grown up institutionalized, she’s had a youth without whimsy. Maggie’s turn is already over; she’s outgrown childhood before it even started.

Then again, the dolls don’t really want Maggie to play with dolls. They want to play with her. Like expectant parents, they have been waiting for someone to come animate their dull days. They have wanted her as she never imagined she could be wanted. The dolls take on kindly parental roles, showing immense patience with their unwilling child.

Significantly, the attic dolls aren’t scary. They comport themselves with starched propriety, asking normal, playing-house kind of things of Maggie.

Still, at first Maggie is alarmed. When one of the dolls moves slowly toward her (when I picture the way these grinning dolls must slowly, mechanically move, then the book does indeed become terrifying), Maggie wonders if they plan to kill her.

The dolls themselves are not actually threatening, but rather wistful, reading and rereading the same scrap of old newspaper about “two lost in a fire.” And yet Maggie repeatedly resists their charming entreaties, insisting on telling them that they are not, in fact, real. Are they real, or are they figments of a lonely girl’s imagination? The book never definitively answers this; as Lois Kuznets writes in When Toys Come Alive: Narratives of Animation, Metamorphosis, and Development, “Cassedy’s doll books insist on some space in which external and internal reality are blurred.”

Why Dolls Creep Us Out

As a 10-year-old, I fervently believed that in the world of the book the haunted dolls were real, in contrast to the other figments of Maggie’s imagination, like the Backwoods Girls she plays with/lectures. Her games with the Backwoods Girls — a gaggle of silly invisible children to whom she must explain everything — is more like how girls typically play. Maggie is the locus of expertise and information to be imparted to the girls. With the attic dolls, though, Maggie is the one being explained to, the one being nurtured. It’s the only way this unparented, unloved girl finds a sense of belonging. She insists that doesn’t need the dolls, but the dolls need her, and being needed is something Maggie has never before experienced.

As a reader, I was primed for this kind of message. Sadly, I thought, I wasn’t an orphan or even abused, and thus unlikely to have any sort of special adventure. But I was an oddball, a shy bookworm, and decidedly a doll girl, heavily invested in my imaginary life. My Cabbage Patch Kid dolls and I had a lasting and intense relationship.

As a reader, I was primed for this kind of message. Sadly, I thought, I wasn’t an orphan or even abused, and thus unlikely to have any sort of special adventure.

What’s fascinating to me now is how similar my own daughter is. Her poison is American Girl, and while she has amassed an inanimate crew shocking in size for a family living in a small New York City apartment, the OG closest to her heart is a now-raggedy Bitty Baby she was given on the occasion of her second birthday (when, coincidentally, I was just about to give birth to her little brother): Special Baby.

For nearly 6 years now, she has taken Special Baby on all sorts of adventures; Spesh has splashed on Cape Cod beaches and ridden the tea cups at Disneyland, traveled by subway and airplane and dolly stroller, and along the way has had ad-hoc reconstructive surgery on every single one of her limbs. Spesh has also gained herself a bit of a social media following: her appearances on Facebook and Instagram are frequently my most-engaged-with, garnering scared-face emojis and typed expressions of agony. Her dead-eyed stare often draws comment, and people lament about the nightmares she will give them.

Why is Spesh so unsettling to adults, when my daughter finds her to be perfectly adorable? It might have to do with her weathered appearance. She’s had such a freewheeling life that she looks antique, and there is something distinctly uncanny about an angelic baby-face that also looks very old. Those two states of being don’t generally belong together. In her great examination of the creepy doll phenomenon for Smithsonian, Linda Rodriguez McRobbie notes, “A fear of dolls does have a proper name, pediophobia, classified under the broader fear of humanoid figures (automatonophobia).” She points out that the sense of creepiness comes from just that contradiction: you’re invited in, but there’s that vacant stare; the doll looks like a cute baby, but is also clearly very old; the figure appears to be alive, but upon further inspection, is not. Our ancient survival instincts trigger alarm warnings at familiar-but-off behavior.

Why is Spesh so unsettling to adults, when my daughter finds her to be perfectly adorable?

McRobbie cites Frank McAndrew, a psychologist who published a research paper on “creepiness”: “Creepiness, McAndrew says, comes down to uncertainty. ‘You’re getting mixed messages. If something is clearly frightening, you scream, you run away. If something is disgusting, you know how to act,’ he explains. ‘But if something is creepy… it might be dangerous but you’re not sure it is… there’s an ambivalence.’” This helps me to understand both why people find Spesh so unsettling, and why Maggie recoils from the china creatures in Behind the Attic Wall — it’s the uncertainty, the ambivalence, the neither-this-nor-that-ness of it all.

Then there is the trope of the possessed doll, which must have arisen from this very ambivalence. The idea of a doll animated by devilish forces has wormed its way into popular culture, gaining wide exposure in movies like Child’s Play, or episodes of the television shows like The Twilight Zone. Who among us has not had a Chucky- or Talky Tina- induced nightmare or two?

It’s spread from our fiction, too, into real life—or perhaps I mean “real life.” Look at Annabelle the Raggedy Ann doll — paranormal investigators reported that the doll’s owners often found it in places other than where they had left it, and eventually concluded that the doll was possessed by a demonic spirit attempting to hopscotch its way into an actual human soul. Don’t worry, the doll now lives in a demon-proof case, in an Occult Museum. (It only seems responsible to point out that the Occult Museum is run by those very paranormal investigators.) Similarly, Robert the doll is a creepy-looking fellow blamed by its child owner for all manner of mischief before being locked in its own demon-proof case. Sounds silly, but to parents who have walked into the kitchen in the middle of the night and startled at a doll left sprawled across the floor, these stories of dolls coming alive and wreaking havoc hit a little too close to home. I personally live with dozens of dolls. What would happen if they were to rise up against me?

These stories of dolls coming alive and wreaking havoc hit a little too close to home. I personally live with dozens of dolls. What would happen if they were to rise up against me?

Ross Chambers examines this idea further in his essay “The Queer and the Creepy: Western Fictions of Artificial Life.” Discussing living dolls like the one in E.T.A. Hoffman’s The Sandman alongside the artificial life created in Frankenstein, Chambers writes, “There is a tradition of Western narrative in the manner of which I call a poetic fable that for two centuries has interested itself in the question of what the phenomenon of artificial life might mean for a definition of the human.” When something that shouldn’t be alive comes alive, he notes, it entails an “involuntary loss of control,” and creates an object that is simultaneously attractive and repulsive.

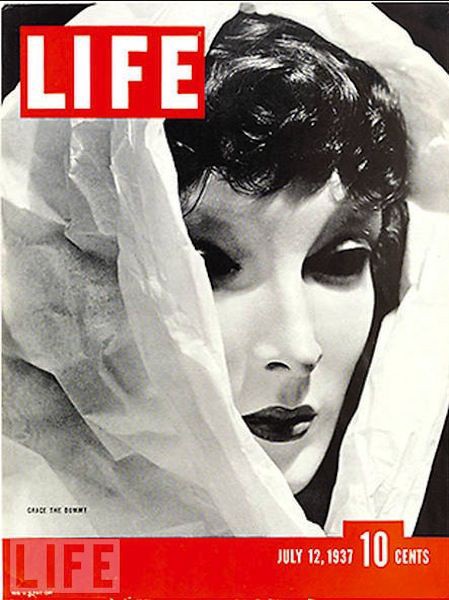

That complicates things, doesn’t it? Here is why the trope of the living doll idea just won’t go away. Because a living doll isn’t merely repulsive. It can also be attractive, even glamorous. I’m reminded of Cynthia, the mannequin who briefly became world-famous, appearing on the cover of Life magazine in 1937. Her creator, a soap-carving-artist (yes) named Lester Gaba, dressed her up, took her about town, and insisted that people treat her like a star. A weird chapter in American history, but what’s undeniable is that she, I mean, it, captured the popular imagination, if briefly. I mean, she had her own talk show, somehow. In a time when America was poised for paradigm-quaking changes, especially in terms of what was asked and expected of women, Cynthia was gorgeous, glam, and so passive her mouth didn’t even open. The subtext is eloquent, no?

In “The Uncanny,” Sigmund Freud claims that the uncanny is an effect of the return of the repressed. No wonder Talky Tina, murderous with rage at not being loved well enough, and Cynthia, beloved and placidly expecting nothing, both haunt us. No wonder we worry when children make their dolls say devilish things that they know they themselves would not be permitted to say, nervously laugh as kids play stern mommies or vengeful teachers. We ask children to repress so much that the thought of it all returning is terrifying. So the idea, which kids are very comfortable with, that their dolls might come alive — to us, it’s quite distressing.

Living dolls indicate a loss of control over where life comes from.

Living dolls indicate a loss of control over where life comes from. I think this is part of what makes Behind the Attic Wall so brilliant; it subverts this expectation. When the dolls need her help, Maggie finds some kindness that was lying dormant in her. Eventually, she gathers things they need, aids them in tea-sipping and dog-walking, helps them fix what is broken. Maggie is a traumatized shell of a girl in the beginning of the book, animated only by occasional fits of rage, but the dolls’ needs coax her back to life. For Maggie, the living dolls become a surrogate family and in the end, they give her ultimate control.

Great Creeps of Western Literature

“The Sandman” might just be the ne plus ultra of creepy doll stories, as Dorothea A. von Mücke wrote in Public Books. 200 years after its publication, it’s still unsettling to read along as the traumatized poet Nathaniel misses all the cues that Professore Spalanzani’s daughter Olympia is a living doll. He confuses the animate and the inanimate–sees doll as being alive, and his actual girlfriend as being an automaton — which leads to madness and, eventually, death. Hoffman was known for exploring the unsettlingly porous boundaries between sanity and insanity. (He also wrote the original version of “The Nutcracker and Mouse King,” which explains how creepy I find that so-called Christmas classic about living dolls, ominous adults, and preadolescent girls getting swept away into alternate realities.)

There are many more notable uncanny dolls in children’s literature, of course. In the same era when I first read Behind the Attic Wall, I loved Betty Ren Wright’s The Dollhouse Murders, and Dare Wright’s The Lonely Doll. There’s Ian McEwan’s The Daydreamer, a truly delightful book that can be read by children or adults and was indeed published in two different editions, an illustrated one for children, and a standard trade paperback for adults (why don’t we do this more often?).

The Daydreamer contains a story called “The Dolls,” in which the protagonist finds that his sister’s doll, Bad Doll, wants her own room, and violently attacks him in an attempt to get her point across, summoning all the dolls to form an angry mob. The scene is predictably frightening:

As Bad Doll inched its way up with cries of ‘Oh blast and hell’s teeth!’ and ‘Damnation take the grit!’ and ‘Filthy custard!’ Peter became aware that the head of every doll in the room was turned in his direction. Pure blue eyes blazed wider than ever, and there was a soft whispering of sibilants like water tumbling over rocks, a sound which gathered into a murmur, and then a torrent as excitement swept through five dozen spectators.

They eventually tear off Peter’s limbs to use as their own. Talk about blurring the lines between alive and not-alive!

They eventually tear off Peter’s limbs to use as their own. Talk about blurring the lines between alive and not-alive!

A new addition to the body of creepy doll lit is Elena Ferrante’s children’s book, The Beach at Night, narrated by a doll who gets left alone (yep, on a beach, at night) and endures a terrifying series of events. (My daughter couldn’t read it for the terror, and I felt her panic — losing Special Baby is a recurring fear in our family.) In one of the most haunting scenes, the Mean Beach Attendant tries to steal the doll’s words, including her name. It is clear in the book that if she loses her words she will lose her life. It’s a fear we can all relate to, I think, and it loops back to the Behind the Attic Wall dolls. In the end, those dolls need Maggie to keep them alive, and when she abruptly stops visiting them, stops talking to them and hearing them, they slip back into the inanimate existence they endured before she arrived.

Making Life Means Making Death

Here’s something to consider: While adults dislike the idea of dolls coming to life, children actively work to give their dolls life. Even the most credulous doll-lover knows that a doll’s life is a tenuous matter, kept aloft by the sheer force of a child’s words, and belief, and love. Children have the gift, the responsibility, of giving dolls, with their voices and names and words, life. It’s something kids know without having ever read The Velveteen Rabbit, in which the toys discuss how the love of a child can make them Real. It’s a compelling idea for children in the process of becoming themselves, becoming Real.

While adults dislike the idea of dolls coming to life, children actively work to give their dolls life.

Of course, giving a doll life means eventually taking it away, too, even if only by accident or eventual neglect. My daughter was moved to tears by seeing a snippet of Toy Story 3 where the lifeless dolls, no longer animated by a child’s love, are being given away. There’s something heartbreaking about the idea that these beloved toys go inert as kids outgrow them, because it’s such a blatant metaphor for the death of childhood — I should know, I sobbed while reading my kids the end of The House at Pooh Corner, when the toys discuss Christopher Robin going away to school and not needing them anymore.

We harbor in our collective unconscious the idea that a child’s love makes stuffed animals like the Velveteen Rabbit and Winnie the Pooh REAL. For children, this is a wonderful idea, one that gives them real agency. For adults, this idea becomes terrifying. Our ideas of reality are less porous than childrens’, and rather than living in a Muppet Babies world where our imaginations create reality, we tend to prefer to know what is real and what is not. We pride ourselves on it, in fact.

This is why Behind the Attic Wall occupies a unique place in the world of creepy doll stories — it stays poised between the child’s view of dolls and the adults’, just as Maggie herself straddles these two worlds. Maggie’s doll-friends are sweet, after all — they just want to have tea parties and clean handkerchiefs, and in this way they imitate the play of very young girls. But they are also ominous — in the end (spoiler alert!) they turn out to be animated by the loitering spirits of the dead Academy founders, the “two lost in a fire.” When Maggie abandons them the life again goes out of them. Maggie, it turns out, was what gave them the ability to live. Maggie’s dolls were never the super-sweet stuffies of early childhood — no Winnie the Poohs or Woody the Cowboys here — but nor are they the evil possessed dolls of horror films and occult museums. They occupy some place in between.

Maggie’s dolls were never the super-sweet stuffies of early childhood, but nor are they the evil possessed dolls of horror films and occult museums. They occupy some place in between.

I hope Behind the Attic Wall enjoys a renaissance, perhaps a new edition with a cover that will appeal more to today’s kids. After all, we need more books about the in-between of things. As artificial intelligence becomes a part of our everyday lives in ways E.T.A. Hoffman and Mary Shelley could have only dreamed of, I’m guessing our kids will bring a special perspective and understanding to stories that blend the alive and the not-alive.

And of course, I hope my own daughter reads Behind the Attic Wall some day. I think that she and Special Baby would really appreciate its blend of sweetness and terror, innocence and knowing. Last Halloween, for example, my tiny sweet daughter decided she wanted to dress up as—what else?—a spooky, undead doll.