Books & Culture

Why I Left Men for Books

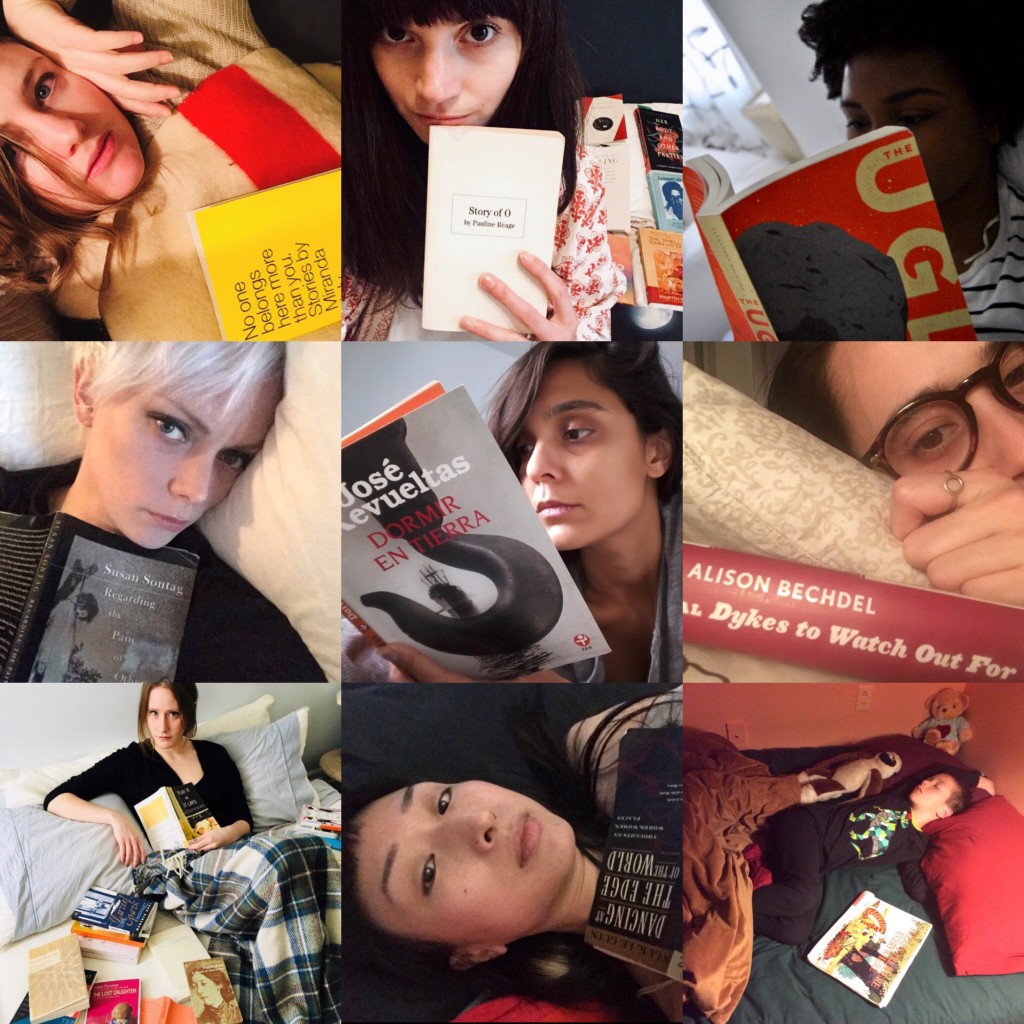

Women’s solitude, and women’s reading, can be a radical act

Two years ago I exchanged a human being — brown-eyed, alert, filled with complex nerve endings and a fluency in several languages — for a stack of books the length and weight of a person, a stack that now occupies the left side of my bed. Do I regret the trade? The short answer is: often. The medium length answer is: not enough to do anything about it. The long answer, because there is always a long answer, is what follows. For, who are we, what are we, if not a combination of books we have read, conversations we have had, regrets and anxieties we have suppressed, and promises we have allowed ourselves to hope for? If each life is “an encyclopaedia, a library, an inventory of objects,” as Italo Calvino suggests, then this is my attempt to re-shuffle the last few years of my life, to understand what it means to be a reader, a woman reading, a single woman who chooses books.

If you asked him, my former human, he’d say I exchanged him for a city, a program in which one is required to read a book a day and not a slim book, a fat one with tiny margins and no dialogue (otherwise known as a Ph.D.). This is not entirely accurate. I didn’t leave him for a city or even a country — but I did leave him, in some small way, for the books I now sleep with. That is to say, I left him for a life that is shaped by the abundance that books offer us but also by the solitude they bind us to.

The pursuit of an intellectual life and the desire for intimacy should not have to be mutually exclusive. Yet, for many women — particularly, women writers, academics, and artists — this continues to be the case. They are faced with a choice between the cultivation of love, companionship and family, and a retreat into solitude and creative work. Of this gendered double standard the poet and essayist Leslie A. Miller writes, “The image of the male poet in retreat can be attractive to society. But the image of a female poet in retreat is somehow against nature, a liability that can lead to emotional bankruptcy.” There is, thus, a form of solitude that attends the female artist, one that suggests deviance, stubbornness, abnormality and precarity.

This leads me to ask: Is there a particular solitude or separateness unique to the female reader? I’d like to pause on this question. For if there is something distinctive about the solitude of the female reader, what form does it take? How does it disrupt the delicate emotional economy in which we live? What does it reveal about our culture’s perception of reading and of women who read?

The pursuit of an intellectual life and the desire for intimacy should not have to be mutually exclusive. Yet, for many women — particularly, women writers, academics, and artists — this continues to be the case.

In the late 18th century, before she wrote her seminal work A Vindication of the Rights of Women, the philosopher and women’s rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft put together an anthology for women entitled The Female Reader. It was designed as a pragmatic guide that would enable women to function as intellectual adults. For her and the other proto-feminists of the 18th and 19th centuries, reading was a technology of access, a way of introducing women (though not including them necessarily) to a worldly conversation. It promised a retreat from domestic obligations and an entrance into public life.

We see the same gesture 200 years after Wollstonecraft in Elena Ferrante’s globally renowned Neapolitan series. One reason Ferrante’s novels are so popular is that they foreground reading as a radical act, one in which we, readers, can participate, revealing the ways in which the female reader causes a threat to the patriarchal order. As a precocious and brilliant child, Lila issues library cards in all her family members’ names in order to access a world beyond the grey courtyards of her neighborhood, though even this does not allow her and our narrator Lena to shape a life that is not patrolled by arrogant, dismissive, and abusive men.

Reading, for these writers, relays a direct access to power. The female reader is a powerful reader. But at the same time, she is a neglectful woman. Is this, then, still the case in 2018? What is the role of the female reader in our era? What is at stake for women when we open a book, when we turn our critical attention away from the demands of our everyday lives and toward the open conversation of the page?

I read, much of the night, and go south in the winter. In university a professor drew our attention to this line from T. S. Eliot’s The Wasteland. The speaker is reading, he said, so that means she is not having sex. The line has stayed with me ever since.

She is reading so she is not conceiving children.

She is reading so she is not listening to you.

She is reading so she is alone.

Or she is not alone but separate. She is in what Frederic Nietzsche calls “the inward cave, the labyrinth of the heart” into which “no tyranny can force its way.” She is reading and so is locked within a solitude of her own making and her own protection.

One reason that the solitude of the female reader might be more political, and more controversial, than that of the male reader, is that time operates differently for women — so we are made to understand. Women’s bodies, we learn, are living clocks, which cannot keep pace with men due to their biological utility. As men careen to the peak of their careers, women are faced with a paralyzing set of questions and decisions to make. Lydia Davis, whose writing has been described as a “grammar of loneliness,” sums it up well in her one-line story “A Double Negative”:

At a certain point in her life, she realizes it is not so much that she wants to have a child as that she does not want not to have a child, or not to have had a child.

By inviting books into her bed, the female reader’s retreat becomes an attempt to find refuge from the impasse that this double negative evokes.

Someone I met on a dating app once told me that at 33 he was the prime dateable age for a man. The prime age for a single woman was, of course, significantly younger. I’m not sure why he told me this. Perhaps to remind me that the cards were stacked in his favor, that men age more productively, increasing in value with each grey hair. As proof he cited charts, assembled by dating sites like OKCupid, exhibiting the “official” decrease of women’s desirability and the increase of men’s desirability. Like two mountain peaks, one red, one blue, they change course over a person’s lifespan. The red (female) peak experiences a quick drop off after the age of 23 while the blue enjoys a long, luxurious decline down the slope of undesirability. Similar charts depict deeply entrenched racial biases (see Hadiya Roderique’s excellent article “Dating While Black”). These charts make painfully legible the systemic racism and sexism that shapes not only our desirability but our desires.

What I have learned over the past three decades and what I am trying to unlearn, is that for women love, durable intimacy, and companionship is an economy of scarcity.

What I have learned over the past three decades and what I am trying to unlearn, is that for women love, durable intimacy, and companionship is an economy of scarcity. With each year our stocks depreciate. As Olivia Laing reflects in her study of loneliness, The Lonely City, single women in their mid-30s find themselves at an age where “female aloneness is no longer socially sanctioned and carries with it a persistent whiff of strangeness, deviance and failure.” This “whiff” of strangeness haunts the female reader as she claims her separateness from the world, when she bows her head to the page rather than the baby monitor.

“There is never a right time to start a family,” a doctor once told me when I went to get a prescription for birth control. “I just wouldn’t want you to regret it later.”

“Do you have children?” I asked her. I had just turned 30.

“Yes,” she said proudly. “I have four.”

Regret. This word takes on a particularly gendered connotation in this instance. Like the Davis short story, I questioned my actions, staring at the birth control prescription (I didn’t use it in the end). I did not want not to have a child, to carry with me that “whiff” of abnormality, failure, and prickly eccentricism — did I? Not having a child, it seemed, was the worst possible case of FOMO a woman could experience in her lifetime. Despite my resistance to societal demands, I could feel myself being pulled in. Now, three years later, even though I’m closer to my reproductive “expiry date,” this anxiety has lessened. This is thanks to the conversations I have had with other women, conversations about the books we are reading, about our strategies of navigating a world that is still largely hostile and blocking rather than enabling to women.

This is something we are particularly adept at: using storytelling and its trivialized genres — confession, complaint, “gossip” — as a means of negotiating, and potentially even dismantling, the impasses that structure our lives and shape our experience of the world.

How to take down the patriarchy? 1. Build a network of brilliant and difficult women. 2. Sleep with more books.

Yet the question remains: does reading make us lonely or less likely to “find a mate”? Or does our dissatisfaction with our societal position, with the dudes we meet online, with the double standards we face in our professional and personal lives, turn us into readers?

Perhaps the answer is: a bit of both.

Reading turned me inward, but not to escape men. To survive men.

I won’t describe my past life, because if I did I would have to describe him. I would have to tell you about how, as we prepared for sleep, he would turn to me and say “last look” before he switched off the light, so that we could memorize each other’s faces in the moment before the blackout. This was so that we would recognize each other if by chance we should share the same dream.

I no longer meet him in my dreams. Or if I do, we no longer recognize each other. As Neruda says, “the same mouth / is now another mouth.” We pass each other without a second glance.

These days I have instead been dreaming of babies — the Instagram famous babies of my friends. I’ve memorized their tiny faces in all the configurations of joy and despair captured by their many daily, hourly, updates. Theirs are the last faces I see before going to sleep. They are my “last look.” And their faces, and the faces of strangers, men on dating sites gripping giant fish or crouching in front of Machu Picchu, ads promoting a new miracle diet (ice cubes and self-discipline), cat videos, pug videos, a heavily documented Christmas vacation, brunch, group brunch, someone’s bathroom selfie, these are the last images to be imprinted on my retina. These are the visions that I bring with me into that horizontal world of sleep, and which, until recently, have dominated my dreams.

I have taken to sleeping without my phone. The phone, a tool of communication, of connection, is also a technology of loneliness.

For this reason I have taken to sleeping without my phone. The phone, a tool of communication, of connection, is also a technology of loneliness. Banished, hypnotic, it pulses in the far corner of my room. But I will not be seduced. I will resist its vibrations with the perseverance of Odysseus at the mast, with the self determination of the ice cube dieter. (Though sometimes I’ll wake up in the middle of the night and stalk across the room to check it.) For now, and I’ve made a rule of it, only books are allowed near my bed.

Tonight, I’m reading in order to examine my own solitude and the solitude of the women around me, who, for whatever reason, have not found companionship through conventional routes. Because of the breakdown of a long-term relationship, a series of disappointing intimacies, or the prevailing insistence on “informal” relationships (where one is not supposed to “catch feelings”), or because of circumstance, or choice, or a refusal to settle, we have become difficult women. Misfits. Killjoys. Ours is, to borrow a line from Emily Dickinson, “The Loneliness One dare not sound”; ours is a political solitude. Yet, as Audre Lorde reminds us, “anger is loaded with information and energy.” Though it may be attended by visceral disappointment and sometimes even despair, it makes legible a broken system. As Laing writes, our “difficult feelings” are not a simply a consequence of “unsettled chemistry, a problem to be fixed, but rather a response to structural injustice.” Disappointment, dissatisfaction, irritation — these are political emotions. They are useful and dangerous. Or, rather, they are useful because they are dangerous.

It is not lost on me that solace and solitude share the same root. I find myself suspended between these two wor(l)ds.

It is not lost on me that solace and solitude share the same root. I find myself suspended between these two wor(l)ds. I sleep amongst dead authors but living books. I sleep beside living authors and silent books that lie, opened, awake, beside me. In a way it is not dissimilar to sleeping beside a lover; there is the alien consciousness, encased in the soft shell of the book. There is the quiet angular weight, the blunt spine, the pages warm and musty as skin. “What makes lovemaking and reading resemble each other most,” Calvino observes, “is that within both of them times and spaces open, different from measurable time and space.” The reader submits to the act of reading. She forgets herself, suspended, as poet Lisa Robertson puts it, “in the vertigo of another’s language.” To be shaped by a text, by the contact with another’s innermost thoughts — this is a form of pleasure.

It is a form of love as well.

For, as the cultural theorist Lauren Berlant observes “what being in love secures is the evidence that you have had an impact in the world by being a condition of possibility for someone else.” To be a condition of possibility for someone else is not only to be someone’s fantasy but to be the conduit for that fantasy. This is not unlike the relationship between the reader and the book.

To love then is to read. To be loved is to be read.

Here, in the lamplight, I enter into a slow communion with my book. I enter into a space beyond measurable time. This becomes my last conversation of the day. Perhaps my most important one.

Books have become my cure to the overstimulation of the screen and the small but cumulative disappointments of my everyday; they have become the soft technology that mediates the hard, flickering machinery of my waking life. They offer a retreat from life but also an entry point into understanding my life. They are more than a consolation prize; they are the trapdoors into what Virginia Woolf in her diaries referred to as “the real world,” the expansive and private world of the mind.