interviews

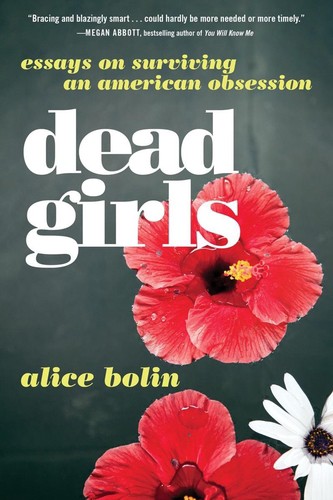

Why Is America Obsessed with Dead Girls?

Alice Bolin, author of ‘Dead Girls,’ on the lurid consumption of young women’s corpses and the ways women survive

Dead Girls explores America’s obsession with women’s bodies as bright young corpses, from TV shows about fictional murdered women (like Twin Peaks, True Detective, or Veronica Mars) to news cycles about real murdered women. But these stories are rarely about women: “There can be no redemption for the Dead Girl, but it is available to the person solving her murder,” Bolin writes in her opening essay, “Toward a Theory of the Dead Girl Show.” “Just as for the murderers, for the detectives…the victim’s body is a neutral arena on which to work out male problems.”

Bolin’s essays enfold a range of American obsessions: mass shootings, reality TV, dehumanization, LA noir, and witchcraft — and the ways women’s bodies inform all of the above.

One week before meeting in person at a conference, we negotiated the time difference between Memphis and Brooklyn to talk about the consumption of fictional Dead Girls, the dehumanizing of Britney Spears, and the ways women survive.

Deirdre Coyle: In Dead Girls, you say you find yourself wanting to apologize for the book’s title because it “evince[s] a lurid and cutesy complicity in the very brutality it critiques.” I can’t imagine it being called anything else. What made you decide to fully lean into that luridness?

Alice Bolin: I knew it was going to be called Dead Girls from the instant I knew that I was writing the book. It definitely did have to do with marketing; in my mind I was like, “people will buy a book that’s called that.” It’s a good title. I didn’t really think beyond that. But as I was finishing the book, I became more and more uncomfortable with the idea of selling it on Dead Girls, because I am critiquing all these other people who are selling their thing that is really is not about women or the struggle of girls at all. Quite often, Dead Girl stories are about men and their problems. But the dead girl is the selling point, or the way in. And I was like, well, am I doing that same thing? It gets to my overall discomfort with whether it’s possible to write a subversive Dead Girls story, or whether there’s a place for those stories at all. So I’m thinking, am I part of the problem, too?

DC: Where did you start in the collection? What was the first essay?

AB: Really, the beginning of the essay collection was when I moved to L.A. and started writing a lot about the noir, and about my experience moving to L.A., and literary L.A. That was where it started coming together because I kept coming back to these crime stories that fascinated me. Feeling lonely and bored and kind of morose, I was drawn to stuff that was really morbid: watching true crime shows and Twin Peaks and going to the graveyard and sulking around. My personal life and my more creative interests were dovetailing at that point.

Quite often, Dead Girl stories are about men and their problems. But the dead girl is the selling point, or the way in.

DC: Was this loneliness related to your renewed interest in the noir?

AB: Yeah, for sure. The famous L.A. noir In a Lonely Place by Dorothy B. Hughes typifies for me that sort of Los Ange-lonely thing. Of course, it’s a huge city, but the kind of loneliness you feel there is a bit perverse, because it’s so beautiful, and the weather is perfect. But there is a lot of dread inherent in the landscape and in all of these natural disasters, or the sort of man-made disasters of urban sprawl and drought. That personal loneliness that I felt I tied to this broader loneliness of the city.

DC: You write that Dead Girls is a “book about [your] fatal flaw: that [you] insist on learning everything from books,” which is very relatable, and probably relatable to most people reading Electric Lit. This seems to apply to your relationship to Dead Girl stories as well as your relationship to Los Angeles (you write about reading Khadijah Queen’s I’m So Fine and Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays). Would you say that your expectations have been dramatically changed by literature in all aspects of your life?

AB: Absolutely. And not just literature. I grew up in Idaho, and in northern Idaho, which is the even more remote and isolated part of one of the most remote and isolated states in the U.S. I was always reading magazines, watching TV a million hours a day, because I was hungry for this world outside what I could see and experience, this world that felt more valid to me than the world around me. So this idea that I could learn everything from reading, or that I could learn about “real life” from reading, comes a lot from that. It’s not a bad thing, and I think that clearly has been my strength — now I’m a cultural critic. A lot of that comes from this voracious interest in the world just beyond my reach. But at the same time, I do think it is a flaw in a certain way, believing what you read more than what you see, more than what you experience, and subordinating my own experiences, or the experiences of the people around me, to the experiences people I consider more important or smart, like Joan Didion. That is how you start to buy into these dumbass myths and romanticized notions.

DC: In your essay “Black Hole,” you talk about two mass shootings in your hometown of Moscow, Idaho. It’s interesting how you can grow up in a place and feel that it’s not “real life,” and it’s boring, but — and you can correct me if you don’t feel this way — when something really horrible happens, it doesn’t make that place feel more like the “real life” that you aspired to.

AB: Right! And I think there’s always been freaky violence in Moscow for a town that’s so small. I mean, it’s a town of 25,000 people. But growing up, there were always murders that happened there, there were always things that you would read about in the paper. I didn’t realize at the time that that level of violence was beyond what would be normal for a town that small. There are lots of reasons why; it does have to do with gun control, it does have to do with it being a little bit of a hub because the University of Idaho is there, so there are lots of people coming in and out, and cultural things, and political things. It affects your self-esteem in a weird way, to be attached to a place where freaky, violent things happen. Where you’re like, what does this say about me? Why did this happen where I grew up? Once when I was living in LA, there were two murders at the laundromat that was thirty feet from my house. And in this very selfish, self-absorbed way, it made me feel terrible. It made me question everything that I was doing, because that kind of violence really taints your experience. I think it has a lot to do with this ambient dread that we experience in America today, with the level of random violence that can happen at any moment. It affects the way we think about ourselves.

DC: Do you think that being around that more than the average person in a small town channeled your later interest in consuming this type of media as well?

AB: Absolutely. I write about this in the book, but there’s a sense in popular culture that the Northwest is serial killer breeding ground. That’s where Ruby Ridge happened; there’s all of these crime stories, even Twin Peaks. There’s this moody, creepy sense that that’s what the Northwest is. I was very aware of that growing up, and was sort of like, “Oh, yeah, sure. There are serial killers everywhere.” It totally channeled my interest at a really young age in horrible crimes, because they were happening very close to home.

DC: There’s a passage in the essay “A Teen Witch’s Guide to Staying Alive” that I found particularly relatable: “I was afraid to make my darkness real by writing it; reading my own dark thoughts was embarrassing and rife with talismanic power. Revising my diary was a ritual to carve those feelings from myself, protecting my inner life even in a space that was supposed to be secret.” Did you ever feel this way writing Dead Girls?

AB: Definitely. When I was writing, I was very conscious of the witchy power of writing, or the sort of magical power or words and letters. You know, a spell is so interesting to us because it’s the words that make something happen. They aren’t just empty; they’re an action in themselves. I don’t know to what extent it’s just human, but in our culture, we do think of words as having this deep power. There’s a level where it feels like when you say something you make it real. And when you write something in a book, it feels more true than if you think it in your head. So I was thinking about that vulnerability, and the scary power that come with writing.

DC: Writing is a socially acceptable power. If you write something down, it changes the fabric of reality, even if it’s just your own reality.

AB: And I think when I first started writing, when I first started writing poetry, I would write poems about boys who didn’t even care about me or know who I was. But in the poem, we could be together, or there could be something going on between us. That sounds so psycho, but for me that truly was something that made me love writing as a college student. I felt empowered by that, that I could change my reality by writing it. And nobody could say anything about it, and nobody could do anything about it. Clearly I’m more interested now in writing things that are truthful, or discovering the truth, instead of slanting the truth or making a truth that I want to be real. But at the same time, I do still feel like you create a persona, or you craft a self, and that is empowering, being able to revise or revisit a past self.

DC: Throughout these essays, your concept of Dead Girls expands to encompass not only the fictional Dead Girls of shows like Twin Peaks or True Detective, but also living celebrities like Britney Spears and reality TV stars like Alexis Neiers. It’s obviously not a direct comparison, but how do you think public consumption of these celebrities relates to our consumption of fictional televised dead girls?

I think about Britney Spears as a ‘living Dead Girl’, somebody who was so coveted by the culture that essentially she became no longer human.

AB: The connection is metaphorical in some ways. I think about Britney Spears especially as sort of a “living Dead Girl.” Especially at the time of what we think of as her “breakdown,” there was truly this hunger for her, to know what she was doing, to talk and gossip about her, to follow her and document everything she did. It really was a dehumanizing process, basically. Somebody who was so coveted by the culture that essentially she became no longer human.

But the subtitle [of my book] is “Essays on Surviving an American Obsession.” I’m also really interested in stories of survival, and the ways that women outrun the Dead Girl, or the ways that women are actually able to become women, and no longer girls. Some of those stories, like about Britney Spears, or Alexis Neiers, or even Lindsay Lohan, are compelling to me because these women, despite all odds, didn’t die, didn’t succumb, and did find a way to survive. Even if it’s not how we would have wanted them to survive, or even if it’s not the story that we would have chosen for them. They did make it through.

DC: That’s one way that you make the book about women. There’s a line in your introduction, “I have tried to make something about women from stories that were always and only about men.”

AB: Yeah, I think so, too. And often, those stories that we make about women are not going to be completely satisfying, or they’re not going to fulfill our moral or ethical ideas about the ways that women should live their lives. But the fact of our culture, and the double-binds that women are put in, mean that survival often does take those dissatisfying paths.

DC: You also say in the witchcraft essay that “It’s clear that if both good and bad witches are going to find ways to survive, their methods will not always be ones we approve of,” which is a similar idea.

AB: That’s one thing that I’m thinking about in [the essay] “Accomplices” too. Like Patti Hearst, white women often survive because of the ways that we are willing to mercilessly cut off other people who we could be helping. So I want to think about the ways that women survive, and do that without judgment, while at the same time trying to encourage people to think beyond survival, to a more fair society.

White women often survive because of the ways that we are willing to mercilessly cut off other people who we could be helping.

DC: There were a number of meta moments in the text, where you step back and address your readers. To me, the most striking was in the essay “Just Us Girls,” where you write that the teenage girl characters in the movie Ginger Snaps, “in their transgressions and their transformations, are still participating in a narrative authored and perpetuated by a society that desires for girls to be wild, perverse, and ‘in need of the civilizing hand of man.’” And then — I gasped when I read the next line — “I am attempting to avoid these traps sprung in the narratives of female experience, like I’m winding my way through some sort of feminist labyrinth — how do you think I’m doing?” There were a number of moments like that in the text that I found really striking, and I wondered if that happened organically for you, when you were writing?

AB: I can’t remember exactly in that essay. That may have been a result of some back-and-forth with my editor, where I just decided to address the elephant in the room, which was, ‘I’m talking about how difficult it is to write it is to write a feminist story, and how difficult these constraints are of what is feminism and what are we allowed to do and not allowed to do.’ And so I was like, well, maybe I’ll just explain what I’m actually trying to do and let the reader decide. Because I’m interested in those negotiations that we have to make to make a feminist text. And to what extent I want to play with being transgressive, or push the envelope, or question received political notions, while also being ethical and appropriate and not just recreating stories that are satisfying but maybe, in the end, not empowering.

I’m speaking in a lot of abstractions, but in Ginger Snaps, two sisters have this suicide pact because they don’t want to grow up and become a part of this really gross, sexist society. But one of the sisters sees that if they kill themselves when they’re sixteen, they’re playing into this culture that wants them to be dead girls anyway. They have no option. It’s an impossible situation.

Writing this book, I came up against that problem many times, of having no way to be a “good feminist,” in Roxane Gay-speak. So I left it up to the audience to decide. It’s something I learned from poetry, too. I had a teacher in grad school who said, ‘Sometimes you should just write in the poem what your hope for the poem is.’ I’ve always found that in essays it works, too. Write what you’re actually attempting to do, and let your audience decide whether that’s what you’re doing or not.

DC: This is a selfish question, because it’s something I want the answer to. Maybe I’m just looking for recommendations. Do you still consume, or enjoy consuming, the conventional Dead Girl story?

AB: Not as much as I used to. My tolerance for violence has actually gone so far down, through writing the book. Even watching Killing Eve, which I think is great, I was like, “Ugh, I can’t do this.” At times I would have to turn it off because it’s so violent and horrifying. Analyzing my connection to some of those stories made me enjoy them much less.

I talk a lot in the book about our addiction to narrative, and that if something is a good story, we implicitly think that it’s true, or that its values are valid. And I think that’s totally wrong. Often a good story is feeding us really bad politics. It’s like a spoonful of sugar that helps the politics go down. That’s why I just watch YouTube videos of people putting on makeup. I can’t even deal with these stories anymore. I overanalyze them to death.